Alanson Partridge Brush. Remember that name. Because it was according to his patents that Cadillac put into production something that Honda and Alfa Romeo took decades to match. Mr. Brush’s invention? Variable valve timing.

The information I am about to relate should be a welcome addition to any pedant’s armory of trivia. In 1903, the first production Cadillacs rolled out of the factory, fitted with chain drive and single-cylinder Leland and Faulconer engines—engines equipped with variable valve timing—built in accordance with patents held by Alanson P. Brush. This was not some sort of bizarro failed Edwardian experiment of which two or three were made, recalled, and destroyed. These cars were mass-produced and hugely successful for the era, tens of thousands having been sold. In its early years, Cadillac marketed itself on reliability and economy, something it could do thanks to that ingenious variable valve timing system.

Let’s go back to the beginning so we can understand why this happened, and how it works. If you’re a fan of automotive history, you probably already know that before founding the Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford had founded the Henry Ford Company. Things didn’t quite work out between Mr. Ford and the people in charge of the company bearing his name, however, and he was paid to leave.

In need of someone to appraise the company before liquidation, the company brought in Henry Martyn Leland, an engineer and builder of engines. Leland knew a good thing when he saw it, and sensing an opportunity to sell his engines, he convinced the company to reorganize instead.

In that reorganization, the Henry Ford Company became Cadillac, with a new Henry (Leland) in charge, and Mr. Ford went his own way. Mr. Leland, brought along Brush, an employee of Leland and Faulconer, to come work at the new Cadillac.

In 1903, Ford and Cadillac both released their first series-produced cars. They look remarkably similar outwardly, as they should, because Henry Ford oversaw the design of both of them. The key difference was in motive power. The Ford Model A used what was, by 1903 standards, a very modern horizontally-opposed twin cylinder engine. It had heads cast en bloc, and side valves. The Cadillac used what was, at first glance, a rather more conservative single-cylinder design. Supplied by Leland and Faulconer, the big IOE engine didn’t look much different from a lot of early single cylinders. In detail, though, it was quite different. Visually, the copper water jacket (another patented idea of Alanson P. Brush) was the biggest indicator that this was something else.

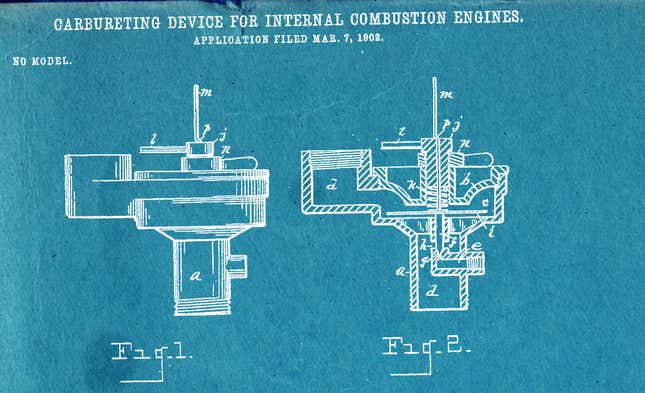

The engine, dubbed the “Little Hercules” did not have a carburetor, or a throttle for that matter. The fuel-air mixture was supplied by a mixer, a mechanism which is not quite fuel injection, but not quite a carburetor either, and was better known in marine applications as a “mixing valve” in the early part of the last century. The operation of the mixer is exceedingly simple. With basic maintenance, it’s also reliable, which is something carburetors were decidedly not in 1903. An incoming charge of air flows into the mixer, and in doing so strikes a baffle which lifts a weighted needle valve from its seat, allowing gasoline fed by gravity from the fuel tank, to flow, to mix, with the incoming air. And that’s it. There’s no choke, and there’s no throttle, no float or float bowl. Aside from an adjustable spring which limits the travel of the needle valve to adjust the richness of the mixture, there’s not much to adjust. Aside from the needle itself, there’s not much that can wear out.

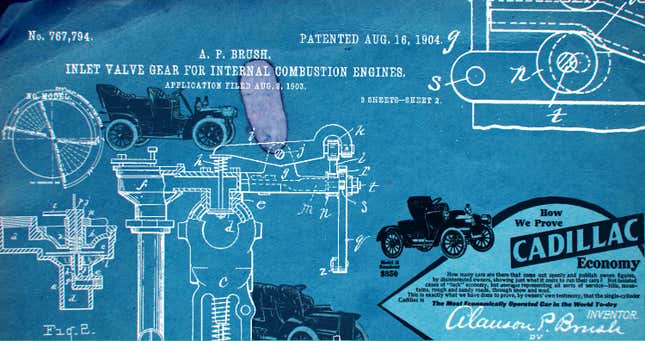

If you’re mechanically minded, you’ve already spotted a problem with this simple mechanism. It’s fine and dandy for an engine that only needs to run under constant load and speed (as was more or less the case when mixing valves were used in marine applications) but how is that going to work in a car? Enter patent No. 767,794 “INLET VALVE GEAR FOR INTERNAL COMBUSTION ENGINES” filed August 3rd, 1903, and granted August 16th, 1904 to one Alanson P. Brush. Alanson’s invention allowed the driver of the Cadillac to have control over the intake valve’s duration and lift, negating the necessity of a conventional throttle for control of engine power and speed. In 1908, Ernest E. Sweet, then chief engineer of the Cadillac Motor Company, wrote to The Horseless Age to explain the purpose and function of Brush’s variable valve timing:

...it is desirable to have the inlet valve open and close practically on centres in an engine that is designed to run very slowly, say, for instance, 100 r. p. m.

It is also recognized that in engines that are designed to run at 2,000 r. p. m. it is desirable to leave the inlet valve off from its seat from 60 to 90 degrees past centre.

The “centres” Mr. Sweet refers to are Top Dead Center (TDC) and Bottom Dead Center (BDC): the position of the crank when the piston is at the top-most part of its stroke, and bottom-most part of its stroke, respectively.

Since it is not possible have an automobile engine run at a fixed revolution (as it is with a stationary engine), it is desirable to have a variable valve timing which will more nearly meet the conditions at the varying revolutions, which is accomplished in the single cylinder Cadillac motors in a large measure.

For the extreme slow speed work our inlet valve does not open until the piston has traveled out on the suction stroke about 1 1/2 inches [out of 5" total stroke], and closes a little past the next centre. Whereas for the extremely high speed work our inlet valve opens 12 degrees past centre and remains open about 77 degrees past the next centre, and there are about twenty gradations between these two extremes which change the time of opening and closing and also the lift of the inlet valve proportionately.

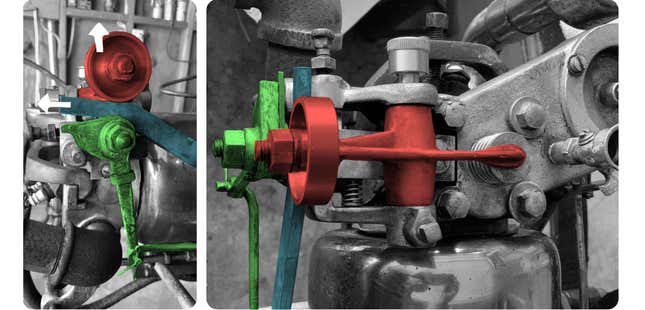

At idle, the intake valve (or inlet valve, as Mr. Sweet calls it) was open for 114 degrees of crank rotation, and “wide open” its duration was 245 degrees. This variation in timing and lift is controlled by the driver with a hand lever. How this was achieved is delightfully simple. The intake valve is operated by a roller rocker. Under this roller is the push rod, which is squared, and has a ramped end. Under the ramped end of the push rod is a cam, fitted with its own roller which is connected to the hand lever by a linkage. The push rod slides between the cam and the rocker roller, and the ramped section of the rod rides up the cam, pushing the rod against the rocker roller, opening the valve. The cam can be rotated to move the end of the push rod closer, or further, from the rocker. The closer it moves the sooner the valve opens, and the longer it is held open, et voila, variable valve timing. The pushrod itself is run off an eccentric, in a manner reminiscent of steam engine practice.

As it happened, 1908 would be the last year Cadillac would offer single cylinder cars. The pace of development in the first decade of that century was rapid, and while the design’s extreme simplicity and ruggedness had been a selling point in 1903, by 1909 buyers were looking for something more sophisticated. Ford had begun selling low priced four cylinder models in 1906, and the Model T which had just appeared in 1908 was set to dominate the low end of the market. Cadillac moved on and never looked back. Improvements in carburetors since 1903 had removed the reliability advantage once held by the dead simple mixer, and as it went, it took with it the first mass-produced variable valve gear.

Alanson Brush had already left Cadillac by this point, to pursue other endeavors. He worked on the short-lived Oakland, creating for it an upright twin cylinder engine, which featured a pioneering use of a balance shaft. Reportedly, a pencil could be balanced on end, atop the cylinder head of a running Oakland engine, so smooth was its operation. Then he worked on what was likely his most famous product, the Brush Runabout. This inexpensive single cylinder car was the first to feature coil spring suspension for both front and rear axles. Unfortunately despite its sales success, the Brush Runabout Company was brought down by poor management, and defunct by 1914. Brush reconnected with Cadillac later in life, when he was hired by General Motors as a consulting engineer. He passed away in 1952.

Various vehicle manufacturers tinkered with variable valve timing in the decades since, but by the time it reappeared in the 1980s on production Alfas and Hondas, Cadillac’s pioneering role had long since been forgotten. By the time BMW introduced continuously variable valve lift to manage engine speed, in 2001, Brush’s patent was 98 years old. Brush’s invention is almost incredible in its prescience, offering variable timing, duration, and lift, and doing so reliably in a production vehicle over a century ago. It is a shame then, that this early success goes almost completely unrecognized in this age of a multitude of various systems, VTEC, VVEL, Valvematic, Valvetronic, aiming to achieve the same goals. So here’s to Alanson P. Brush and Cadillac, the forgotten pioneers of variable valve timing.