To get to Roland George’s shop in Brooklyn, you take the A or C trains out to the Shepherd Avenue station, deep into the part of the city where the tourists don’t visit. But all the world passes through New York, and all the legions of Saab devotees up and down the Eastern Seaboard pass through Swedish Auto Service in East New York, the shop that Roland George has run for the past two decades. It is the last establishment in Brooklyn to specialize in Saabs: a rare beacon, for a dying breed.

It’s funny: you can find anything in New York, if you look hard enough. Venture far out enough and you can find any language, buy any vital and exotic spice, dive through any treasure trove of obscurity, get anything rebuilt, spiral through any rabbit hole—imagined or literal—that the human heart can fathom. You can even find someone who knows how to work on the most niche modern car of all.

Everybody moves to New York for a reason. When George was 12, he emigrated to Brooklyn from his native Trinidad and Tobago. He planned to attend college for business management. To pay for tuition, he took a job working on cars, apprenticing for three years with Ranford Palmer, the former master technician at Zumbach Sports Cars in Midtown Manhattan, whose overall history dates back to 1905, when it once serviced Bugattis and Duesenbergs. By the time George arrived in New York, Zumbach was almost exclusively hawking Saabs and Audis. Palmer set out on his own, founding a shop called Swedish Underground. George followed. And when Palmer eventually retired, moving to Atlanta, George took over.

There are zero Saabs in Trinidad, George laughed. The year was 1999, “just at the height of the Y2K scare,” he remembered. “And I was like, oh, what a time! You know? I called [my mother], I was like mom, I found this shop, and I’m working on weird cars. I’ve never even heard of it. You know what? I think I’m going to take a year off, and I’m going to do this. And after much, much convincing, she agreed that OK, that’s what you wanna do, then that’s what it is. I’ve never turned back. And now, here I am.”

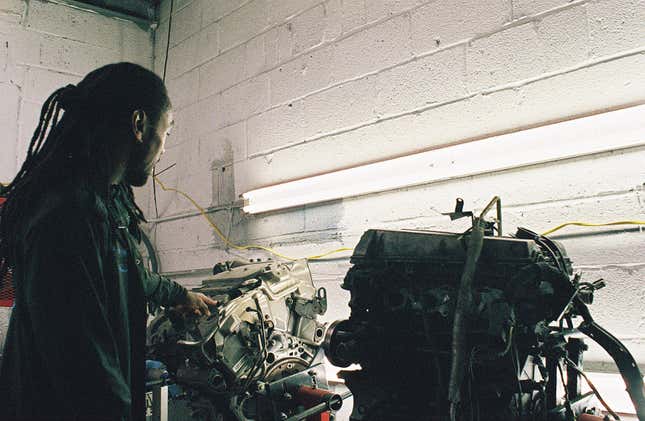

George (right) is youthful and lean, with shoulder-length dreadlocks and a warm handshake. He seems perpetually happy, despite the dreadful cars he works on. On a sunny weekend, he showed myself and Raphael Orlove around: There was a 900 convertible with an American flag painted on the hood, an early 9000 with a blown motor that was his personal project, a few engines he was rebuilding, his wife’s 9-3 wagon, and a handful of modern Saabs in for maintenance. His daughter Renee, a senior in high school, told us about her plans to go to art school, of taking summer courses in photography with NYU. He embraced her for photos. “She used to go to all the Saab meets,” he said, holding his hand out, “when she was yea high, in a Saab jacket.”

In those early days the classic 900, with its longitudinal front-drive setup and bizarre engine/transmission positioning, piqued his interest. “Why is this so challenging for every other mechanic? I wanted to see why that was, while figuring this stuff out. Not that Saabs are complicated, it’s just that there’s one way to do it. Once you get that down, it’s so simple. Just follow the formula.”

For me, the Saab enthusiasm began as irony: the kind of tongue-in-cheek shitposting that has always lent itself to a persona of obsession, the interjection of a bizarre facet of human civilization into seemingly every conversation that surrounds me, all as some sort of bit. (Which one of my garbage Saabs are you?) In middle school, I had tried to talk my professor father into buying a 9-3, because that was what professors drove, if you believed in such automotive stereotyping, which I certainly did. Nowadays you can buy a parts-car 9-3 for the price of a decent Timex, but it is worth remembering that before their demise, they were once status symbols—what novelist and former Saab dealer Kurt Vonnegut once called a “sleek, powerful, four-stroke yuppie uniform.”

“Brooklyn has become a sophisticated metropolis on its own,” said Mark Skinner of Zurich Classic Motors, “and has now attracted a large, youthful, professional base, that has somewhat of a disposable income and are interested in the retro fashion of modern classic cars.”

Skinner first moved to New York in 1985, and has watched the world change around him. He has known George since 2013. At Skinner’s garage by the Gowanus Canal, where he keeps six Saabs and one leering freak of a Lancia Delta, George did something rare: He made a house call.

“He came with a whole air conditioning diagnostic machine, which could fit in the back of a 9-5 wagon,” said Skinner. “He brought his shop to me. That speaks volumes. Again, it wasn’t some crazy extra charge and all that. His easy manner, certainly easy yet knowledgable. Nothing’s gloom and doom, it’s just—this can wait, that’s immediate. The sort of things that you look for in a mechanic. Not to strike terror into you.”

It has always been an arcane business. Like me, an old Saab is rarely considered sexy: it is upright and oddly-proportioned, defiantly angular, painfully rational. A 900 brochure goes on and on about ergonomics, wraparound windshields, cargo space, accident avoidance, the thermal efficiency achieved through the low-pressure turbocharger. Every car has their adherents, but Saab owners have to talk longer and louder about why they bought one. It doesn’t help that the parent company (and, recently, the largest source of Saab parts in America) went out of business.

In New York where obscure chrome-bumpered giganto-barge street survivors with sneering grilles and cockeyed visages still hole up in the East Village, mangled and eccentric and impervious to street-sweeping tickets, you can go months, even years without seeing a vintage Saab. Even this city has its limits.

For 15 years, George’s shop was located at the corner of Atlantic and Classon, in Clinton Hill, Biggie’s old neighborhood. (His one-room shack by the Clinton-Washington C train stop is now renting for $4,000/month.) He moved once, sometime in the end of 2013, across the street: from the garage of a BP gas station to his own space, a squat yellow building. The property upon which the BP station sits, now closed, is worth nearly nine million dollars. Bars in the neighborhood wear names like Glorietta Baldy, Sisters, and Friends And Lovers. For a long time the only way to spot George’s shop was to look for a wall of tires from the Flat-Fix next door, then a sign half-covered by graffiti and reading in hand-painted letters: “ATTENTION LANDLORDS our FUEL OIL Price Is Right!”

Also, look for the street-parked Saabs, which the staff had to move every week for street sweeping.

The operation went swimmingly until earlier this year, when the lease was up for renewal.

The landlord planned to increase the rent by a “crazy” amount, said George. He had been given sufficient notice. But the landlord vacillated: maybe Swedish Underground could stay at the current rate, or maybe the rent would go up, but not by that much. And then, just before the end of the lease, the landlord made a decision: The building was to be demolished. “So I was like, well, dude, you’re telling me that we can leave it at the current rate, but now... I was like that’s it, I’m done.”

George had cars he was scheduled to work on. He had to find a new place, and meet his deadlines. “I just did it out of the garage at my house,” he shrugged. His garage was in Long Island. So he painstakingly towed every single car back to his home, put in the extra hours, and as he tells it, got the work done.

Daven Johansen is 36 years old, lives in Brooklyn’s Windsor Terrace with his wife and two toddlers, and works in construction management. He grew up with Saabs. His dad had a Saab 96, then every single Saab model since, and now a 9-5 wagon. His brother had Saabs. His cousins and family friends from Long Island to Williamstown, Massachusetts have only owned Saabs. At age 3, Johansen remembers watching the road pass through the rust holes in the floorboards of his dad’s 99 EMS, the shock of cold rainwater whenever they rode through a puddle. Johansen now owns five Saabs. His wife drives a Saab, without any extreme displeasure. Johansen estimates that he has owned 17 Saabs in his life. So it goes.

Johansen has known George for 14 years. This past June, he found out that George was about to lose the lease on his shop. “I felt helpless,” he told me. “I felt that if I raised a couple grand, it would cover the cost of him moving shops. I know he had at least three to four customer cars to move, tons of toolboxes, and at least three giant lifts. The crushing price of real estate and doing business in the city is unimaginable. A hard-working guy like him, running a business. Everyone comes to Roland. He’s the guy.”

So at the end of June, Johansen set up a GoFundMe to “Save Swedish Underground.” He penned an ode to George and his character, describing the time he saved Johansen’s wife’s 9-5 wagon: “Roland not only saved my wife from a disastrous day, he also possibly saved my marriage in the process. A lot hangs in the balance when we force high-mile old SAABs on our significant others.”

Out of a $10,000 goal, the GoFundMe raised $480. Six donors chipped in up to $100, high for a crowdfunding campaign.

“I told him, it was completely not necessary, but he did it anyway,” said George. “It was a nice gesture.”

Playing the optimist, Johansen later wrote in an email: “the auction did not raise anywhere near what I’d hoped, but Roland was back up on his feet again in his new location so quickly, the whole endeavor was probably unnecessary.”

For a certain generation, moving to New York seems like a rite of passage: all your friends end up here, at some point, here to spend their twenties or thirties, to thrive and make jokes about the L train and the hated mayor and the bar where cool kids go to get laid. Or, they fulfill the Great Migration westward to Los Angeles, but not before penning a tedious essay.

Restless, full of smoke and stench and electricity. I moved here in July during a never-ending heat wave, when the entire city smelled like the bottom of a trash compactor and the sweat clung to my shirt like a bear hug. I looked for steady work. I street-parked my Saab. I moved it twice a week, laboriously, and the car protested until I left it at another shop in Gowanus for a week and a half. If New York was the place to thrive, then I was here as an innocent: maybe my dream job was just a train ride away, my future spouse around the corner, my ideal apartment scored via an app. Keeping a car in the city is a foolhardy maneuver, but if I just took the train enough, I could alleviate my carbon footprint and therefore my sins.

George’s new shop is in East New York, south and east from everything we imagine about Brooklyn, a few blocks from a line of modest auto-body shops designated as the Auto District. Compared to his previous shop on Atlantic Avenue, he now has three times the room for cars, and it is close to the C train, a necessity for his customers. There is a yard and lifts both inside and outdoors—no more street parking. Inside are gloss-white tiles curving over an archway, denoting early 20th-century history—a gasoline station, perhaps, during the early years of the automobile. A few weeks after he moved in, he had new concrete installed—which took two days, 14 men, and eight cement trucks to lay down concrete eight feet deep. To commemorate this new beginning, George pressed Saab badges into the fresh concrete.

Next to the shop a seven-story apartment is under construction, some squared-off mixed-use monolith dropping onto this block like a Tetris piece. The developers agreed to install an awning, to protect his customer’s cars from the debris. What kind of housing could one expect in this part of town, where 30 percent of the population lives below the poverty line? George shrugged. “What is affordable, really?”

New York is ever changing, always in flux, the relentless churn felt below our feet, above our heads. George is a practical man; he and his team of mechanics welcome the additional space, the accommodating lease, the architectural details. And yet, George pushing his shop ever further east is inevitable, and not surprising—it just matches the migration patterns of New Yorkers. Every day this city enacts consequences upon us beyond our control. A 9-3’s water pump snaps, a piece of scaffolding falls, a landlord reaps a windfall, an iconic bar nearly closes. The reason why so many of us transplants end up here is to look for something, whatever that might be, buried deep within our own hopes. And yet, when aspirations keep eluding us, what is left to aspire to?

For now, it feels, George is in a good place, literally. His shop is bigger, he has his cadre of loyal customers, and perhaps most importantly, he has carved out his niche. Talk to most Saab owners and they won’t stop at one Saab, even if it causes extreme displeasure to their wives. Saab is a car usually admired ironically, but it turns out that they’re good cars. People fall in love, and then they can’t help but hoard them, holding on as long as they can, believing in the brand’s longstanding, supposedly independent streak—which comes with a shred of irony, considering its final years as a neglected arm of the then-largest carmaker on Earth. “They’re coveted, and they’re beloved, and I love that,” said Johansen. “Whether it’s the turbo fanboys with the flatbrims and Monster stickers driving a 2004 9-3 Aero modified through the roof, they get a real thrill out of driving them and talking to other people.”

There are still cars in New York. Too many, perhaps, with all the problems that they’re capable of causing in urban spaces. And there are still car enthusiasts in New York: who might recognize the futility of cars in cities, who take the subway daily, who believe in congestion charges and banning cars in Manhattan—but still wish to unwind up the Taconic or Merritt Parkways during leaf-peeping season, to run up to Vermont for ski trips, to hold onto automotive history, to rediscover lost artifacts. As Kurt Russell proved, sometimes you just need to escape from New York.

Some of these escapees happen to like Saabs, for some reason.

“Not only the last one, [George is] the only one,” said Skinner. “I know of other European car shops, but there are no specialty Saab shops. That’s what he does. He does Saabs.

“New York’s a tough city. People are like, ‘this guy’s wasting my time.’ Never got that from him…he’s always happy! It’s hard to find a mechanic who’s joyous, happy and free.”