Jonathan Leo loves his cars, but not commuting in them. He lives in San Diego and works for the Navy, so he takes the city’s trolley to work as often as he can. Then, on the weekends, he unloads his 2012 Mercedes Benz C250 on some of California’s best roads.

Cities across the world are re-examining the role of the automobile. More specifically, and especially among American cities, they’re trying to get more people to commute like Leo.

This is happening because, in many cases, policymakers have realized that they cannot continue to grow by adding more people who use cars as their sole transportation method, to say nothing of mitigating the never-ending gridlock and poor air quality that exists today. To take just one example, the Boston Globe recently published a series of reports on the city’s horrendous traffic that encapsulated not only Boston’s conundrum, but many of our growing metro areas:

People can no longer reliably navigate a region cursed by its own success...The question is now front and center: Can Greater Boston continue to thrive — or even function — without fundamentally rethinking its relationship to the car?

And the answer is as inconvenient as it is true: Not for long.

Outside of months-long journalistic investigations, there tends to be a template for these debates, a template in which one is either pro- and anti-car. Cars are either evil or the best thing that ever happened to mankind. It is, like so many other debates, presented as a binary choice with no middle ground.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Indeed, it isn’t this way. Transportation is about balance, about options, a concept people like Leo intuitively grasp.

I reached out to Leo and several other self-described car enthusiasts in an unlikely place: the notoriously anti-car Facebook group New Urbanist Memes For Transit-Oriented Teens, better known as NUMTOT. It’s a place for people (not just teens) to share news, memes, and pretty much anything else about “new urbanism” concepts like dense multi-family housing, walkable neighborhoods, and environmentally friendly transportation such as cycling and public transit.

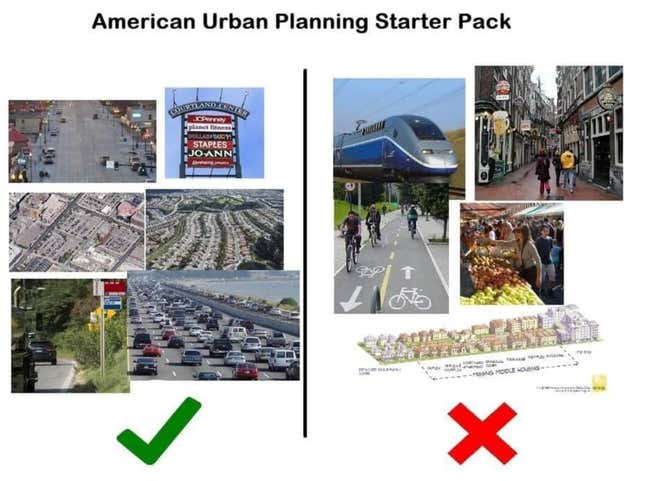

In short, it’s a lot of stuff like this:

But not all of its 177,000-plus members are totally anti-car. I’m not going to name names, but some of your favorite car bloggers are verified NUMTOTs. As are car aficionados of all walks of life.

I reached out to Leo and some other NUMTOTs because one of my blogs had been posted to the group—in which I begged people in Manhattan to stop taking Ubers to the Empire State Building and use the subway instead—with the caption “Very numtot article from a decidedly non-numtot source.”

This sparked a discussion in the comments about the relationship between car enthusiasts and public transit. Leo was one of them:

Car guy here! I love transit, hate traffic and seriously think we need more travel options, bus lanes and TRAINS! I really love my car. I don’t want to end up hating it because I have to deal with traffic and parking every day.

Another, Kyle Metscher, said:

Car guy here. I would rather drive beautiful machines, built with artistic and performance vision, for competition and leisure instead of crawling along a massive slab of concrete cutting through the middle of town in a boring econobox.

What Leo and Metscher and others I spoke to for this article told me, if not explicitly then at least in spirit, is that one can be a car enthusiast while still advocating for—not to mention frequently using—public transit.

Danny Harris, executive director of Transportation Alternatives, a New York City-based nonprofit that advocates for more equitable transportation solutions, echoed those sentiments.

“You can be a car enthusiast and also be an environmentalist,” Harris said. “You can be a car enthusiast and be an urbanist. You can be a car enthusiast and care about public health. We’re not competing with each other.”

To some, this may sound like a completely banal observation that, of course, car enthusiasts contain multitudes. To others, this will be absurd and totally anathema to what it means to love cars. That’s why it’s important to acknowledge that loving cars does not—indeed, should not—mean hating all other forms of transportation.

In fact, there’s very good reason with plenty of historical precedent for car people to be among those most invested in ensuring we have strong public transit systems.

Robust public transportation would give people the choice—the freedom—to use whatever means of getting around they desire, unclogging roads for the people who want to drive, like Leo’s weekend jaunts in his Mercedes.

Another enthusiast of both cars and public transit, 22-year-old University of California Santa Barbara student Ryan Driggett, put it slightly differently. The way he sees it, the majority of people don’t like driving, but have to. “They are as enthusiastic about their generic vehicle as I am my washing machine.”

When searching for a more sensible transportation landscape, people often look abroad, and particularly to Europe. They invoke the likes of London’s congestion pricing, Paris’s road diets, or Oslo’s car-free downtown to show how it can be done.

But one does not need to look across oceans or even to other countries to see the possibilities. One needs only to look back in time.

America once had a balanced transportation landscape, one with choice and some semblance of freedom through the 1940s—of course, transportation itself was racially segregated in much of the country during this time—until the federal government put nearly all its weight behind the automobile.

For the first few decades after the Model T, cars were still mostly used by families for leisure and adventure activities. As documented by historian Kenneth T. Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontier, a history of the suburbs—which is just as much a story of transportation as housing—the affordable automobile rapidly replaced family outings on the streetcar but not so much commuting trips:

Offering more freedom and luxury than the older and more uncomfortable streetcars, the car replaced the trolley and bus for discretionary travel. As the basic mode of journey-to-work movement, acceptance was slower.

Jackson cited a study of 68 cities in 1933 that found despite the Model T’s popularity “commutation by foot or by public carrier was more important.” Historian Joel Tarr has found much of the same. As late as 1934, 45 percent of Pittsburgh wage earners, for example, owned a car, but very few of them used it for commuting; 28 percent walked to work, 48.8 percent rode the streetcar, 1.7 percent used commuter rail, and “only” 20.3 percent drove. The story, Jackson writes, was similar in most American cities.

Those numbers look very different today. According to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, 76.4 percent of Americans drive alone to work. Roughly five percent of Americans take public transportation, although 30 percent of public transit commuters are in New York City alone. To put this in perspective, the same number of Americans work from home as use public transit. Almost twice as many Americans carpool.

In Pittsburgh specifically, to compare with that 1934 survey, 55.5 percent of city residents drive to work today, more than double the amount from 85 years ago. Meanwhile, only 17.9 percent take public transit, and 10.7 percent walk. In the county as a whole, 71.5 percent of commuters drive to work, roughly in line with the national average.

These statistics tell a story of imbalance. As Jackson details at length in Crabgrass Frontier, starting around the 1950s the suburb became the dominant American neighborhood and the car its transportation system, because suburbs are not dense enough for efficient public transportation.

This was no accident. Jackson concludes quite forcefully that this was not a market-driven process of people voting with their feet for a preferred way of life, but the result of a massive, nationwide social engineering project with the full weight of the federal government tipping the scales. Since Jackson’s book was published in 1985, his findings have been reinforced by generations of urban studies historians.

First, there were the houses. “No agency of the United States government has had a more pervasive and powerful impact on the American people over the past half-century than the Federal Housing Administration (FHA),” Jackson wrote. The FHA standardized lot sizes and even specifications for the homes themselves. This is partly why every mid-century suburb looks and feels the same.

More infamously, the FHA graded neighborhoods based largely on ethnic population, minority neighborhoods receiving the lower grades and marked in red (thus the term “redlining”). The FHA would only provide mortgage insurance to bank loans for homes in neighborhoods that good good grades, which, because of the standards the FHA set for itself, overwhelmingly meant neighborhoods outside city limits.

As a result of these deliberate policies, through the 1960s, it was easy and cheap for white people to get a mortgage in a white suburban neighborhood, and nearly impossible for non-whites to do the same. This, combined with building age requirements and lot size restrictions, meant FHA guarantees were heavily tipped towards suburban single-family homes, not urban apartments. And those homeowners earned a number of tax breaks that renters did not, including but not limited to the mortgage interest deduction. These government policies, Jackson documented, made owning a suburban home cheaper, in many cases, than renting an urban apartment.

Not only did the government enact policies that nudged people towards buying suburban homes, but it paid for the roads that went there, at a time when it did not pay for mass transit systems that did not.

In the mid-1950s the Eisenhower administration started its $101 billion federal highway program that, among other benefits, provided quick entrance and egress from cities to far-flung suburbs.

As part of the Interstate Highway program, the government created the gas tax, the proceeds of which could not be used for anything other than highway building and maintenance. This cemented a structure by which the government subsidized nearly all road-building and nearly no mass transit, which was still commonly regarded as a private enterprise that ought to be profitable in its own right. One U.S. Senator, Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, found that, prior to the 1960s, about 75 percent of federal transportation expenditures went towards highways while only one percent went to urban mass transit.

In the years since, this imbalance has gotten slightly less lopsided, but remains lopsided nonetheless. While the 2016-2020 FAST Act authorized $305 billion towards highway construction and repair—an average of $61 billion per year—states receive a grand total of $11 billion a year on average from the Feds for public transit; and that was before the Trump administration started withholding transit funds. Even if the Trump administration quits reneging on those funding promises, that still amounts to about five times as much funding for highway and roads as mass transit, even though 31 percent of Americans live in urban areas.

The story of postwar America, as far as transportation is concerned, has been a complete loss of balance. It is the story of complete and total dedication to the automobile, followed by a woefully inadequate response from local, state, and federal governments that largely maintains what we now consider the status quo of highways, gridlock, an endless sea of red brake lights, and fear of change.

Therefore, we are in the situation we are in now, where car ownership is not a choice but, for nearly all Americans, a necessity.

“In the 20th century, the car became part of who we are,” a recent editorial in The Guardian bemoaned, before concluding that “car culture as a whole also needs an overhaul.”

But what, exactly, does The Guardian, or anyone else for that matter, mean when they talk about breaking “car culture?” Enthusiasts aren’t entirely unjustified to be wary of such pronouncements, as they rarely come with a description of what part of “car culture” they want to break.

Harris, executive director of Transportation Alternatives, said he can’t speak for everyone who uses the phrase, but for him, it’s not about making people who love cars to stop loving them. It’s about allowing those who don’t to stop needing one.

“At least when I talk about car culture and breaking it,” Harris told me, “I think most people are not fully aware of how much their lives are given to this system that’s so much beyond them but is about how they live, how they get around, what they prioritize, what they choose to fight for or not.” Here, he is not talking about enthusiast culture. He’s talking about what we have called commuter culture.

Harris likened commuter culture to a societal addiction, one that is furthered by the billions of dollars car companies spend on advertising to try and differentiate their crossover from someone else’s nearly identical crossover that never show their machines being used the way they typically are, in bumper-to-bumper traffic. Breaking the car culture, Harris believes, requires admitting nearly all Americans are completely dependent on cars to function for reasons outside of their control.

Critically, Harris stressed, it’s not about removing all cars from society, or telling people they have to stop being enthusiasts. After all, Harris grew up reading Motor Trend; once upon a time he lusted after a ‘66 Mustang.

“Breaking car culture is not taking cars away from people,” he said. “It’s giving people safe, equitable, and dignified transportation alternatives...I don’t think our goal is that people who drive, we’re sort of aggressively taking away the things that they love or the things that they need. But instead, we’re actually giving them very genuine, safe, equitable options of getting around.”

Getting to that place, getting that balance back, requires re-thinking what our streets and roads are for. Rather than measuring everything by how many cars can get through a traffic light cycle or how more lanes could increase throughput, Harris wants the focus to be on moving people rather than just cars. In rural or suburban areas, that might not change a whole lot. But in denser areas, it might.

Fundamentally, what everyone I spoke to for this article are in favor of is a simple proposition: Make driving a choice again, and give the roads back to enthusiasts.

In some cities like New York and the aforementioned capitals abroad, this is already underway to some extent. New York’s City Council Speaker and 2021 candidate for Mayor Corey Johnson, for example, regularly invokes the term “car culture.” But most Americans still cling to commuter culture. It is time to let go.

Enthusiasts can, and should, lead the way demanding better, because they have everything to gain. The only way to drive free is if the roads are open.

Correction 2:36 p.m.: A previous version of this article stated Leo drove a 2012 C230. His C230 was actually his previous car, a 2005. His current car is a 2012 C250. I will never forgive myself for this error and forfeit my Journalism License.