Carroll Shelby, as anyone who’s seen Ford v Ferrari can tell you, went from creating and distributing the AC Cobra to running the racing operations of the entire Ford GT40 program. And engineer-slash driver Ken Miles came with him, whether Ford wanted that or not.

Anyone paying attention to the background in shop scenes may have also noticed a wood cutout that eventually turns into one race car prototype, and then six. That car is the Cobra Daytona Coupe, unmentioned in the on-screen story of the GT40's development.

While the film gave the cars some camera time, it ignored the reality that the rise of the GT40 is a direct result of the abandonment of Shelby American’s own Cobra Daytona Coupe—a choice made against the wishes of Ken Miles.

Before there was a Cobra Daytona Coupe, there was an AC Cobra. The simple result of the marriage of an off-the-shelf small block Ford V8 and a previously-unremarkable AC Ace sports car, Carroll Shelby’s Cobras were the ultimate customer racing car throughout North America. A powerful and balanced sports car that could be bought out of a shop and immediately driven to a track to win any race it could legally enter, the AC Cobra was an accessible weapon that defined a brief era of a category of American racing.

As a car meant to be sold to customers, however, it had one flaw. While it was devastatingly effective on American tracks, its open cockpit design was an extremely poor fit for European endurance racing, where longer tracks with longer straightaways greatly punished cars with any sort of major aerodynamic flaw.

One day in 1963, Carroll Shelby decided to go up to his lead designer, former GM employee and LA Art Center student Peter Brock, and simply ask him to build an enclosed body for the AC Cobra.

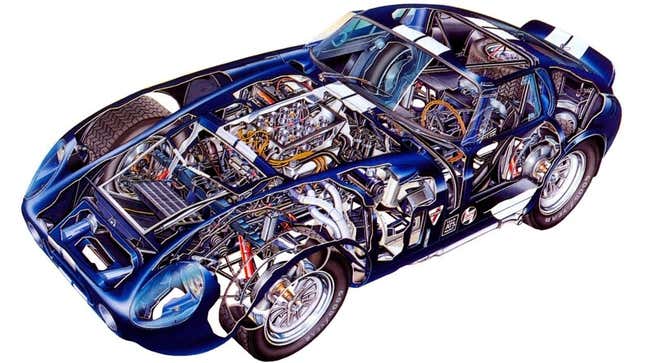

Despite his experience at GM, Brock was not yet, at this point, a successful car designer. But Shelby American was a strange place, and Shelby trusted Brock enough to hand him free reign to create. Shelby’s sheer lack of oversight gave him the space to try something wild if he wanted, so he attempted to copy the works of Dr. Wunibald Kamm, a German doctor whose works Brock discovered while at General Motors. The aerodynamic concepts, as Brock told Road & Track in 2015, were impressive, but, “The shapes... looked so strange that no manufacturer was willing to put them into production.”

The radical kammback design came together quickly, with the first body built in Los Angeles before six others were made in Italy by an outside group working off Brock’s measurements. Testing of that first car began immediately at the nearby Riverside, where Miles quickly adapted to the car. He broke the team’s personal track record by over three seconds. The improvement was immediate and undeniable.

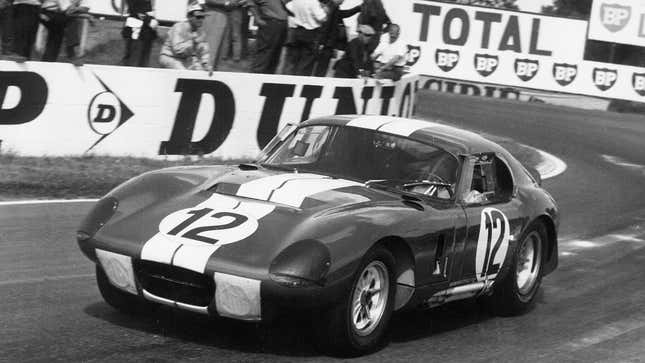

The cars debuted at Daytona, in the same class as the Ferrari 250GTOs and eyeing them as primary competition. The advantage was unexpected but clear. Even more unexpected was the pace of the car overall. The car won its class on the way to 4th overall in 1964, the first year of the Ford GT40 program, but driver Bob Bondurant thought the car could have won the whole thing if not for an issue with a damaged oil cooler forcing the team to run carefully for the second half of the race.

With Shelby American shifting focus to the GT40 program, the Cobra Daytonas ran with moderate Ford support under a different banner in 1965. They won a World Championship, the first prophetic instance of a Ford team toppling Ferrari’s stranglehold on all aspects of European sports car racing.

Ford, as a company, did not care. Even Carroll Shelby, it seemed, did not care. But Miles still believed in the car, and so did Brock. Miles, in fact, believed the car had more potential than the Ford GT he would ultimately become so famously associated with.

In ‘64, the Cobra Daytona Coupe team attempted to put the same sort of big-block engine that propelled the eventual winning Ford GTs into one of their cars and go for an overall win. The car was not completed in time for that year’s Le Mans, and the marriage of Ford and Shelby American ensured that the team’s interest in finishing that project for a shot at the overall win in ‘65 died with the car’s development.

The Cobra Daytona Coupes, still promising and the last cars with any real potential to win Le Mans overall with a front-engine design, were all but abandoned in Europe for months, never to be developed further. Instead, Brock left Shelby American to build a prototype racer for a Japanese company called Hino before becoming synonymous with racing Datsuns later in the decade.

Miles eventually had no choice but to turn his focus to the lone remaining top-level racing project at Shelby American, leading to Ford’s factory-backed wins in 1966 and 1967, the latter of which coming as a result of the radical GT40 MkIV based on the entirely American-built J-Car Ken Miles was testing when he died.

By 1968, regulation changes marked the end of the GT40 MkIV program and of Ford’s involvement in developing top-level racing cars. As a result, just three years after the Cobra Daytona Coupe won a championship overseas, racing was abandoned at Shelby American.

The legend of the GT40 only grew, but the Daytonas were scattered to the wind. It would be decades until Peter Brock’s creations were so much as considered collectible again.