A few years ago, Mustapha Harb realized there was a problem in his field of research about how autonomous cars will change the way people travel. The solution to the problem he settled on was as simple as it was revealing.

The industry was making big promises about how great self-driving cars would be for society, and those claims were attracting billions of dollars of research from the world’s biggest companies to make the technology a reality.

One did not have to look far for studies and articles suggesting fleets of self-driving cars could, for example, reduce traffic. These techno-utopian articles claimed the same highways we use today could, with slight modifications, accommodate many more autonomous vehicles than they do human-driven cars. AVs could, using more precise control systems, follow one another at much closer distances. Similarly, lanes could be narrowed, accommodating perhaps six lanes where there are only five today.

These promises were, and remain, the foundation upon which AV utopianism has been built: a greener, safer, faster, and more pleasant transportation future just around the corner.

But, Harb found, these promises couldn’t be checked. After all, self-driving cars didn’t exist yet.

Harb, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California Berkeley’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, was intimately familiar with the research already done on the subject in his field. Most of it consisted of surveying which, while far from perfect, was the best approach available.

“You would send people a survey,” Harb described, “like, hey, there’s a self-driving car in the future, how do you think your travel will change in the future?”

These studies, flawed as they were, found something very different from the rosy future AV companies wanted investors and the public to imagine. They found reason to believe AVs would drastically increase the number of vehicle miles traveled, commonly shortened to “VMT” in academic literature.

And the more vehicles miles traveled, all else being equal, the more traffic and emissions we can expect, canceling out many of the AV’s touted benefits.

But Harb knew these studies sounding the alarm about a high-driving future were speculative at best. For one, what people say they will do when asked by a survey question is often different from what they’ll actually do in the real world. On top of that, it’s especially hard for people to predict what they will do with a technology they have never experienced, as in the case of self-driving cars.

While the survey results were potentially alarming, it was difficult for researchers like Harb to put too much stock into them. Some surveys predicted only a few percentage points increase in VMT in a self-driving car future. Others, upwards of 90 percent.

Harb figured there had to be a better way. And he knew it was imperative for researchers to get at this question before AVs became publicly available and their societal impact already came to pass.

But his advisor, Professor Joan Walker, had an idea. What if they hired chauffeurs to drive random people around?

The chauffeur, Walker outlined, will do the driving for you. And, just like the most optimistic AV future of fully autonomous robot cars zooming around, you don’t even have to be in the car.

“All these things the self-driving car can do for you in the future,” Harb summarized, “a chauffeur can do for you today.”

The concept, once it reached published form, elicited praise and jealousy from other researchers. “It’s delightfully clever and brazenly simple,” gushed Don MacKenzie, head of their Sustainable Transportation Lab at the University of Washington. “I wish I had thought of it.”

Using 13 volunteers (a very small sample size due to budgetary constraints) from the San Francisco Bay Area who owned cars, Harb and his team studied their travel patterns using GPS trackers on their cars and phones for one week, then gave them a chauffeur for a week who would drive the participants’ personal vehicles for them. Finally, the researchers observed the subjects for a final week to look for any changes returning to their chauffeur-less life.

For the week they had the chauffeur, the participants could use them for 60 hours total (again, budget constraints), including for journeys in which the subject was not in the car. This was to simulate the potential use of an AV as a kind of personal robot.

For example, the chauffeur could bring the kids to soccer practice and back or drive a friend home and then return to the house. They could even pick up groceries and make a Target run to simulate a driverless car future where items could get bought online and loaded into your AV by a store employee before returning home.

Harb readily admits the study is not perfect, nor is it likely to prove the most accurate predictor of what our autonomous vehicle future looks like. But it is, by many estimates, the best first approximation we have.

And that approximation is, in key ways, a vision of things to come.

Harb thought they would see people sending their cars out more than if they were driving themselves, something like a 20 or 30 percent increase in VMT with the chauffeurs. Nothing to sneeze at, of course, but towards the middle of the wide range of the results the surveys had suggested.

He was wrong. The subjects increased how many miles their cars covered

by a collective 83 percent when they had the chauffeur versus the week prior.

To put these findings in perspective, when researchers looked into the impact Uber and Lyft have had on urban congestion, they reported an increase in VMT in the single digits. San Francisco, which has seen some of the largest percentage increase of cars driving around in its downtown thanks to Uber and Lyft, had an increased VMT of 12.8 percent.

Knowing how much gridlock and traffic those rideshare cars have added to the city, imagine six and a half times as much car driving as that is almost impossible.

To be clear, nobody, not even Harb and his fellow researchers, think this 83 percent figure is a precise measurement of what our AV future looks like because their sample size is too small. Even their follow-up study, which is currently in progress and features 53 participants is not meant to be definitive.

And the study design does have flaws. For one, MacKenzie pointed out that participants knew in advance when they would have the chauffeur and could have planned accordingly, shifting some trips from their normal week to their chauffeured week. But, on the other side of the equation, the study would not account for long-term changes to travel behavior based on AV ownership, like moving further out into the suburbs or taking a job with a longer commute.

But none of the researchers Jalopnik spoke to believe those flaws detract from the overarching, real-world conclusion: AVs will change people’s behavior in profound ways. MacKenzie called it “probably the best data we have based on actual, measured behavior.”

This is not the first time car companies have positioned their products as keys to a utopian future.

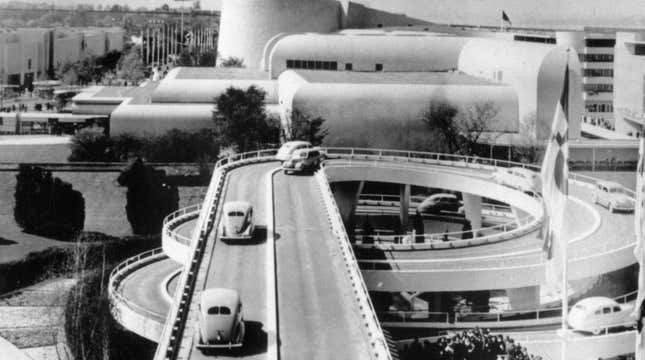

For the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City, General Motors commissioned “Futurama” exhibit for the “Highways and Horizons” portion of the fair. The exhibit, designed by industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes, is still regarded as one of the most influential demonstrations of urban planning in the field’s history. It showed Americans a powerful company’s vision of the future, a company that would gain the financial and political might to help make that vision a reality.

“Here is a highway intersection,” the promotional video touted at one point, “highway engineering at its most spectacular. Traffic may move safely and easily without loss of speed…” It went on to predict, in a grand, lofty narrated voice straight from old Hollywood, that highways will re-shape the American way of life, that “without tedious travel, the advantages of living in a small town are within easy reach, bringing the people who live there into closer relations with all the world around.”

It predicted cities would become “much larger, rebuilt and re-planned” for modern needs, separating industrial centers from where people work and play. “On all express city thoroughfares,” the film went on, “the rights of way have been so routed as to displace outmoded business sections and undesirable slum areas whenever possible.”

“Man,” the narrator proclaimed with his trademark pretentiousness, “continually strives to replace the old with the new.”

As did GM. In 1956, the company came out with another future-of-transportation spot, this one in musical form. It’s a strange little film to modern eyes, what with the singing and all. But, like the Futurama exhibit, it predicts a future—1976 in this case—in which cars largely drive themselves.

One of the through-lines between GM’s 1939 and 1956 visions of their respective automotive futures is that technology can and will solve the biggest inherent driving annoyance: traffic.

In the 1939 exhibit, bridges, GM pronounced, would bring about “the elimination of congestion,” as would highway interchanges and better planned urban centers. Never mind that the city hosting the World’s Fair, New York, already had plenty of bridges, which brought about even more congestion; it would, of course, build more, with the same results.

Meanwhile, the entire premise of the 1956 short was that the family of four trying to get away on vacation is stuck in maddening gridlock, but when the son adjusts the radio to transport them 20 years into the future, all of a sudden they’re gliding along clear roads, presumably thanks to technology.

GM’s Futurama vision was hardly on point, but a surprising amount of it came to pass—for better and for worse. Cars and freeways did dominate the American landscape. They did not put an end to congestion.

The “advantages of living in a small town” did indeed come within reach, as tens of millions of American families relocated to the suburbs after World War II, meaning they had to drive farther to work, to school, to restaurants and movie theaters and other forms of entertainment. All those extra miles, multiplied by the millions upon millions of people driving them, has rendered the gridlock problem impossible to solve simply by building more lanes and more roads.

Now, AV proponents once again look to cars to solve the problems created by the vision car companies had wrought.

The logic behind how AVs will reduce traffic or reduce emissions—that there will be less space between cars, and cars will communicate with each other to flow more quickly and less erratically than with humans behind the wheel—is fundamentally no different than the arguments made in those old video clips, which maintained that more space for cars in the form of new lanes and new roads will do the same.

Today, we have roughly 80 years of experience that has demonstrated it’s not that simple because when new roads and highways make traveling faster over longer distances possible, people change their behavior and restructure their lives to account for that. As more and more people do this, the roads fill up, resulting in rush hour gridlock and longer commutes for everybody.

What experts are gradually concluding is that, should AVs be widely adopted, the same cascading series of events is possible, perhaps even likely. Not only will they not solve the problems created by car commuter culture, but they might make it worse.

“If you think AVs are going to solve these long-standing problems,” warned Marcel Moran, a PhD candidate in city planning at the University of California, Berkeley who studies autonomous vehicles, “you’re wrong.”

Still, there may be a path forward. It is a path that learns from the mistakes of previous eras, the mid-century highway building and the idea that private car ownership should be the primary, if not sole, method for getting around. It is a path in which AVs can serve a broader social good, one that not only involves them being safer than human drivers—which none of the experts I spoke to doubted would eventually come to pass—but also puts them to intelligent use.

It is, however, one that does not necessarily guarantee AV companies a profitable return on their billions of dollars of investment. In short, nobody has really figured out how to make money off this yet.

For this reason, the chauffeur study’s value, Harb believes, is not so much in that 83 percent figure, but in digging into the specific trips people made and why they made them.

Broadly speaking, Harb separates them into two categories: good VMT and bad VMT.

Good VMT are trips that further some societal goals, such as allowing people with mobility issues to make trips they normally couldn’t make.

“The whole point of transportation is to allow people to do the activities they want to do,” Harb summarized, and good VMT allows people to do those activities independent of health restrictions, to say nothing of restrictions of inconvenience and embarrassment of coordinating another way of getting there.

For example, the participants who had the largest increase in VMT were retirees. Initially, those same retirees to a person told Harb they thought they would not be good study participants because they may be afraid to drive at night and some on highways. But Harb assured them that it didn’t disqualify them from participating at all.

In the end, every single retiree used the chauffeur to go to Napa for wine tastings, something they had wanted to do for a long time but didn’t feel comfortable doing themselves. They also used the chauffeur to go places at night or they could only get to via highways.

On the other hand, there’s bad VMT, or trips that generate high amounts of “zombie miles”—trips where the car is not transporting any passengers, or is replacing public transportation, cycling, and other some other available means of getting around.

When asked for an example of bad VMT, Harb cited one study participant who, prior to having the chauffeur, took public transportation to work because parking near their office was prohibitively expensive. But, when they got the chauffeur, the person got dropped off at work and then, to avoid the cost of parking, had the chauffeur drive their car all the way back home, only to come to pick them up again at the end of the day. This person effectively doubled their VMT just so they could avoid parking, a scenario AV researchers warn as more or less the worst-case scenario of an unregulated AV future.

But not all of the miles added to San Francisco area roads thanks to the chauffeur fit neatly in one of those two buckets. Call them “mixed bag VMT.”

For example, every participant sent their chauffeur to run an errand for them, either dropping off a package or filling up gas or going to the grocery store. These trips could qualify as bad VMT because they’re zombie miles. Plus, the fact that the cost to the car’s owner for running these errands is effectively zero will likely result in far more errands being made with little concern for doing them in a somewhat efficient manner.

Forget something? Who cares, send the car back. Circle town three times because the errands are programmed in a nonsensical order? No worries, you’re at home watching TV anyways.

But, it wasn’t all bad. Harb reminded me, “People were really happy about the extra time they had because they didn’t have to run all these thoughtless errands like going to the grocery store or picking up their own pizza.” It doesn’t seem right to classify these trips purely as bad VMT if people got to spend more time with their kids or get some extra work done because of them.

This whole good/bad/mixed bag VMT conundrum is why several transportation researchers Jalopnik spoke to for this story favor a simple mechanism for letting people decide for themselves which AV trips are worth it and which ones aren’t: charge them for it.

Researchers haven’t reached a consensus on a preferred policy—when do they ever?—but they generally agree, even independently of AVs, road use needs to be taxed in a smarter way. Right now, the gasoline tax functions as the major road use tax, and researchers generally dismiss it as a clumsy mechanism that doesn’t impose the actual cost of driving, including road maintenance and the cost of sitting in traffic, on drivers. Plus, a gas tax will be rendered useless by the rise of electric vehicles.

So, researchers suggest moving away from the gas tax and towards other forms of road use taxes. Ideally, they generally prefer per-mile usage fees, perhaps even ones that change according to the time of day or density of congestion. Either way, they broadly agree that policymakers should move towards taxing the hell out of zombie miles.

Or, as David King, a researcher at Arizona State University, succinctly put it, “now’s the time to tax the robots.”

King added, “this is a chance for us to reset the rules,” referring to how cities regulate road space and tax road usage. This jives with Harb’s takeaway from the study, the good VMT versus bad VMT dichotomy, in that there are some AV uses that forward societal benefits and others that are mere excesses.

Harb believes there isn’t much time to set these policies in place. During just the single week people had chauffeurs for his study, he saw people already getting comfortable with their AV future. When the study ended, people begged him to keep the chauffeur longer and wondered how they could possibly go back to running their own errands again.

He worries that, should people become comfortable with using AVs under current laws and policies, it will become exceedingly difficult for cities to curb the technological abuses sure to follow.

“It’s going to be very, very difficult to take away something from people after they got used to it,” Harb warned, which is why he considers it vital that the policies be put in place before people do.

After discussing all the possible ways our AV future can go horribly wrong, I asked Harb how he felt about it, if he came away from this study thinking we as a society might be better off without AVs.

Even though he watched people abuse the concept through his studies, and probably has a better window than anyone into how some individuals will put their own selfish, greedy needs before the well-being of others, he isn’t willing to go that far. Because he also saw senior citizens living a more fulfilling life and parents getting to spend more time with their kids or cook them more nutritious meals. He has seen the whole range of possibilities.

“This is the thing, it can be a really, really good future,” Harb assured me, as long as rules are put into place that prevent people from abusing the technology. ”We can live in that future.”

But it wouldn’t look as good as a promotional film.