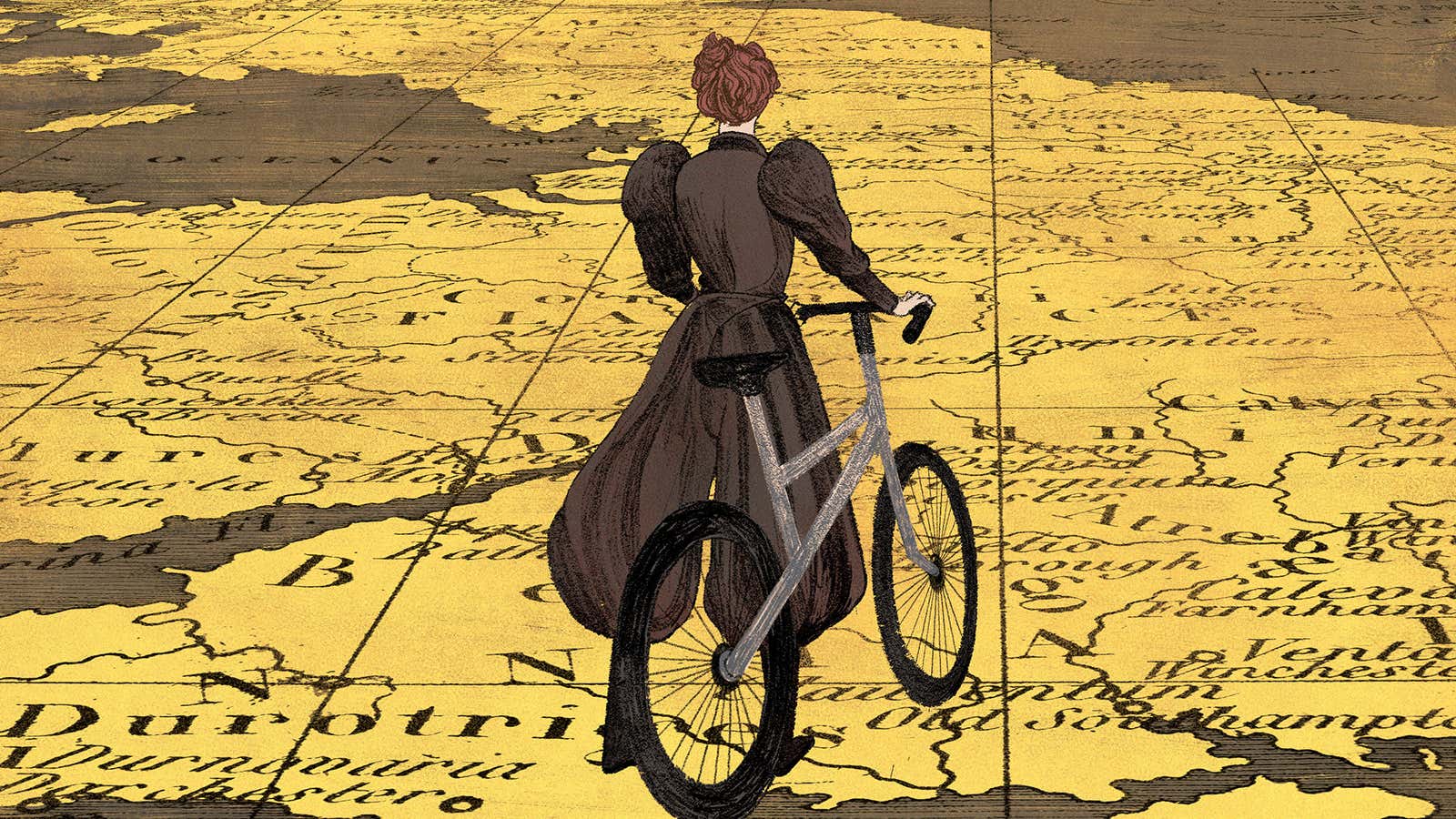

In 1897, Cambridge students lined the streets to protest a vote that would grant women the right to earn a degree at their prestigious all-male university. The budding shitheads of the turn of the century launched rockets, threw eggs, and hanged an effigy of the powerful “New Woman” from a building and subsequently mutilated it in the streets. That “New Woman” was identified by one defining accessory: her bicycle.

The world began to change when women first climbed onto the bicycle. In an era when they were confined to the arena of domesticity, women suddenly had an affordable method of finding independence. Once they did, the worlds of both mobility and social change would never be the same.

Bikes boomed across the world in the 1890s as a breakthrough affordable mode of transportation. They were cheaper (about $3-15) and far easier to use than a horse and buggy ($150 for the horse), let alone a car (easily $750 around the turn of the century). In a time when the average person would earn a weekly salary of $10.06, buying a bike was the first big piece of tech for affordable, personal transportation.

Suddenly, the average person could easily travel out beyond the home.

Women and Bikes

Up until the early 1900s, women were intended to be masters of the domestic sphere, as noted in Unmentionable: The Victorian Lady’s Guide to Sex, Marriage, and Manners by Therese Oneill. They cooked, cleaned, took care of children, and generally did not leave the house unless escorted by the prominent male figure in their life—a husband or a father. That meant no formal involvement in things like business, politics, or education.

But that wasn’t going to last long when there was a simple mode of travel (just hop on, balance, and go) laying around.

With bicycles under their metaphorical belts, early twentieth century women started to be around. In shops. In the streets. In parks. They could no longer be ignored or easily segregated—and they could begin to understand how, exactly, life outside the house was lived. And that meant they could start advocating for themselves.

Fashion and Health

Traditional Victorian dress died as the bike drastically transformed women’s clothing. Imagine trying to ride a bike outfitted in a corset, bustle, and multi-layer full-length skirts. It’s pretty much impossible.

Out went the heavy, impractical clothing and in came bloomers, or, essentially what would happen if you sewed a big skirt into a baggy pair of pants and cinched them at the knee.

That was hugely scandalous back then. How dare a woman flaunt her individuated legs and possibly even the shape of her calves! There was even a new “sport corset” that was less restrictive than the traditional corset but also contained a lot of back support—proving that women couldn’t just completely give up certain aspects of the expected dress code.

There are actually a bunch of patents by female inventors dedicated to making cyclewear more comfortable for women. One even included a skirt that came entirely away from the body—which was wild back in an era when that kind of bodily freedom was wholly unacceptable.

The thing about Victorian-era fashion, though, was that it was about more than just practical clothing. It was about morals. Victorians wore so many clothes because it was morally unacceptable to show any part of your body, ever—or even the mere intimation of your body, as evidenced by the bloomers. Before this change in fashion could be embraced, an entire societal shift would need to happen.

What followed was something of a frenzy—accusations that biking was actually very bad for women in many ways, but especially for their health. Bicycling could cause—gasp—physical exhaustion. Doctor A. Shadwell claimed it could cause depression. It was even said biking would cause something called “bicycle face.”

This so-called medical condition appeared in the Literary Digest in 1895 and was characterized by a “usually flushed, but sometimes pale [complexion], often with lips more or less drawn, and the beginning of dark shadows under the eyes, and always with an expression of weariness.” Other sources said bicycle face involved “hard, clenched jaw and bulging eyes.”

The aforementioned Dr. Shadwell wrote an entire article about this godforsaken disease in 1897, which you can read here. His logic is… well, I’ll let you see for yourself:

[The effects of bicycling] are not associated with other far more severe forms of exercise, such as football, rowing, running, swimming, gymnastics. They rather resemble the effects of overindulgence in tobacco or alcohol, and are nearly allied to that affection of nervous origin which is called sick-headache.

In bicycle riding it is the very absence of conscious effort, in the ordinary sense, that misleads the susceptible into “excess”, unless they are warned to look out for a different kind of fatigue.

There wasn’t much consensus about bicycle face, given that it wasn’t a real ‘disease’. It was at once a permanent position and a temporary affliction, depending on who you asked.

Bicycle face was very much like hysteria in that it was a very convenient and oftentimes dubious “diagnosis” for unruly women, something that Maya Dusenbery discusses in her book Doing Harm: The Truth About How Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Sick, Misdiagnosed, and Sick.. These women on their bikes weren’t conforming to the standard that women normally would be by staying home and appropriately dressed, which meant something must be wrong with them.

And, yes—bicycling was said to make women sexually aggressive. Part of that was the physicality of bike riding and the fact that the seat was making close contact with the pelvis. That potential sexual stimulation led to “hygienic” seats—ones that little or no padding where the genitals touched the saddle. The point was to make things so uncomfortable that women couldn’t possibly be aroused. Here’s more from Andrew Denning’s The Fin-de-Siecle World:

Traditionalists fulminated against the idea of the bicycle as an instrument that would instigate a sexual awakening, whether personal, as many people expressed trepidation about a woman straddling a bicycle seat and experiencing the shocks and vibrations of the road, or socially, as bicycles gave women the freedom to escape the watchful eyes of parents and chaperones.

Most of these “diagnoses” and uncomfortable changes were quickly phased out. As more women began to ride bikes—and the world wisened up to the objective benefits of bicycling for everyone—the pseudo-science and the technology that was created to fix it disappeared.

Suffragette Movement

“Let me tell you what I think of bicycling,” Susan B. Anthony told a reporter in 1896. “I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”

If you need a concrete example, suffragette Alice Hawkins used her bicycle to ride around from town to town, organizing bicycle clubs and spreading the word about female emancipation. Being able to travel quite literally gave her and other women the ability to do widespread canvassing to get their political point across.

The bicycle, though, often serves as more of a symbol of female emancipation. Bikes weren’t, say, the required mode of transportation for suffragettes. But because they gave women the powers of relative freedom, mobility, and self-reliance, they quickly became associated with the list of things women were demanding to be allowed to do. Bicycling quite literally showed women that they could go out and do the things they’d been prohibited from doing for centuries—and if they could do that, well, what else were women capable of?

Racing and Breaking Records

As with any wheeled contraption, a widespread adoption of biking by men and women alike encouraged everyone to get ready to race and try to set some incredible records.

There was a surprisingly huge interest in women’s bicycle racing because of its accessibility for the general public.

Men’s bicycle races were events. They were six-day long races that lasted a full 24 hours per day. They were feats of human endurance, yes—but they weren’t particularly easy or even enjoyable to watch. Because women were considered far weaker than men, they weren’t allowed to compete in these massive events, as The Guardian reported. Instead, they were allowed two or three hours of racing a day over the course of several days. Ironically, this shortening of the race time stoked a huge interest in following along because you could actually do so—and because it enabled women to push far harder over a shorter period of time, making for far more exciting events.

It’s a fascinating period. Even though these women were defying the gender norms of the time by seriously training as athletes and even becoming the breadwinner for their family, society still demanded they be feminine. For a while, they were expected to compete in hoop skirts.

But these women said hell no to that. They stripped off all of their excess clothing, opting instead for a more form-fitting long-underwear type ensemble because they weren’t able to expose their arms and legs. The media often portrayed them as petty and jealous as opposed to competitive athletes who were taking their task seriously, as reported by Roger Gilles Women on the Move: The Forgotten Era of Women’s Bicycle Racing. Here’s a quote from the book that really highlights it:

Rivalries were chalked up less to competitive fire than to what the men considered to be petty female jealousy. Stoking such jealousy, real or imagined, was at the very least a way to sell newspapers. [...]

“Pretty Pearl Keyes,” as she was called by Cleveland World, was just seventeen years old, and this was her first race in competition with Dottie Farnsworth, “whose black eyes and midnight hair are quite a much an attraction as her powers of pedaling—and the propellors for furnishing the same,” said the World. Right away Pearl was said to have it in for Dottie. The reason, claimed the World, had to do with the way Dottie’s “captivating smile” appealed to the men and made her the favorite of the crowd, whose shouts of encouragement were said to rankle deep in Pearl’s heart. “Pearl is some peaches herself in the way of pulchritude,” said the World, “and although she has any number worshipping at her shrine, the plaudits for Dottie make her shiver with rage.”

And then there was Annie Londonderry, the woman who set off on her bicycle to circumnavigate the globe, a trip that took 7,000 miles and fifteen months to complete (albeit with the liberal use of trains and ferries). It exemplified the liberation bicycles offered women, proving to themselves—and to the world—that they could do the seemingly impossible. Londonderry did the trip, according to Around the World on Two Wheels: Annie Londonderry’s Extraordinary Ride by Peter Zheultin, to settle a bet in which some men claimed she would be unable to do something that a man had done.

What those students at Cambridge and those false claims doctors were expressing was anger, but also fear. Fear that women, women who smoked, who engaged in politics, who rode bikes, would change the world around them. The fear of seeing women enjoying the “free, untrammeled womanhood” that Susan B. Anthony claimed to feel any time she saw a woman on a bike.

They were right to be afraid. The moment women took off on two wheels, the world as they knew it was never the same.

Update 10/18/19 10:53 AM: A previous version of this quote misattributed Susan B. Anthony’s quote to Elizabeth Cady Stanton. We have corrected the statement and regret the error.