Let’s get something out of the way up front: Ray Magliozzi hates cars. And not in a my-car-is-a-pain-in-the-ass-and-it’s-always-breaking kind of way (though there is some of that too), but in a they’re-killing-the-planet kind of way. “How could you not?” Ray told me earlier this year. “They’re ruining the fabric of our lives.”

Ray says this as if it is the most obvious thing in the world. And it mostly is, of course, but it’s still funny to hear him say it, because for 35 years he co-hosted one of NPR’s most-listened to shows of all time, Car Talk. Ray also owned a repair shop in Cambridge, spending a good chunk of his days fixing cars.

Ray’s life has been devoted to cars, even if the yuks on the radio were thin veils for how Ray and his brother and co-host Tom Magliozzi actually thought, which was less like your local mechanic and more like an engineer. Both Ray and Tom studied engineering at M.I.T., and after all the laughs during each call, the engineer inside them would usually emerge. Your check-engine light is on because of a leak in your EVAP system, Ray might advise. A few seconds later it would be on to the next caller.

Car Talk had a soothingly predictable quality to it. In the beginning, there would be corny jokes, then some callers, then a weekly brainteaser called the Puzzler, and then some more callers, and, before you knew it, it was over. They did this, brilliantly and seemingly effortlessly, for decades, reaching over four million listeners at their peak. It had a surprisingly wide appeal; non-car enthusiasts, and certainly non-car people, will often gush about how much they loved the show.

All good things must come to an end, though. And Car Talk’s end came in the fall of 2012. Tom passed away at the age of 77 two years later. In the intervening years, new weekly shows have been posted online and still run on some NPR stations, but those shows are made up of repurposed content.

Car Talk is still around, but you’d be forgiven if you hadn’t thought about it much. NPR and Car Talk said they planned to stop distributing the show in 2017, but changed their minds. Today, new archive episodes of the show still air on about 80 NPR stations, and are available as podcasts. Ray also still writes his syndicated column every week.

“We have eight listeners now,” Ray says, before a producer, David Greene, jumps in to say it’s actually gone down to six.

More seriously, Greene says, “NPR [tracks the numbers] but I don’t pay any attention to that.”

“We do it because it’s fun,” Ray says.

The numbers hardly matter in any real sense. Car Talk made its point and became a national institution a long time ago. Whatever’s left is gravy.

The show’s most frequent listener these days might in fact be Ray himself. He said he still listens to the show “all the time,” mostly to hear his brother’s voice and remind himself about times they had together. To remind himself of the jokes they shared. To remind himself of the good times.

“I love to hear his laugh, and I love to hear his take on things,” Ray said. “It’s a rare opportunity that I’ve had to still communicate with my brother that most people don’t get.”

When I went to WBUR’s studios to talk to Ray, time stood still for a moment. Ray, seated in the studio, was recording sponsorship messages for the newest episodes, his voice unmistakeable.

He sounded the same as he did when I first started listening to Car Talk in the mid-’90s as a tween. The show was appointment radio. It was reliable, for one thing. You could be irritated by all the laughs, but you also couldn’t deny that Ray and Tom had some serious knowledge about cars, and in a way that you couldn’t really fake. The jokes were mostly corny, but the shtick as a whole was endearing. All of it was 10,000 percent more listenable than most other NPR shows.

Even so, it was hard to quite know what you were listening to. What was with their aliases Click and Clack? Did they really both go to M.I.T.? Before the internet it was hard to get answers to such questions, unless you really went searching. It was never worth the effort, though, and, besides, the air of mystery enhanced the show.

“A lot of people ask [to talk to Ray],” a manager at the Good News Garage in Cambridge—which Ray owned before passing off ownership to a friend—told me. “We still get calls.”

But not a lot of those calls are passed on. Not a lot of the still-considerable amount of listener feedback now gets passed on, either, since Ray inspires a protectionist instinct in the people who know him. When I met him I understood why. Ray is as pure as they come. We spoke for around 45 minutes, though it could’ve gone on for hours, as sitting around and bullshitting was as natural to him as breathing. But Ray was “tired,” at the end of our chat. Which seemed about right.

He and Tom were perfect for radio.

“It’s hardly been heavy lifting, you know,” Ray told me. “I sat here and Tom sat there, and we just talked to each other and talked to whoever was on the other end without any awareness that there were millions of people listening.”

Tom was Ray’s idol from an early age, and that was inspired in part by Tom’s expansive personality and habit of dragging Ray along on trips with his friends.

“[Tom would] be going to a beach party with his buddies. ‘Can I take my little brother along?’ He was 17 and I was five! Who does that? Nobody does that!” Ray said.

Tom also made Ray think he could make it at M.I.T.

“It was hard [getting in to M.I.T.] and it was hard staying in. I didn’t realize that some of my contemporaries who went to other colleges had a lot of fun,” Ray said. “M.I.T. has a way of grinding you down. The way they do it is, you know, when you grew up in high school, you’re the kid that gets the best grades. If you had an exam you’d get 100 in it all the time. And then you go to M.I.T. and if you’re lucky, you’re average. If you’re lucky.

He added: “I would say about 10 percent of the people actually belonged there. They had the academic credentials, the acumen to be there. [Tom and I] were in the bottom part of the other 90 percent. We were there to keep those guys company. Otherwise they would feel lonely. You’re going to have an equations class with three people in it? No.”

Ray, like his brother, studied engineering, but by the time he left had soured on the idea of ever actually becoming one.

“The good thing about it was I discovered I didn’t want to be an engineer. I thought about 30 or 40 year career as engineer, designing windshield wiper links for Chrysler,” Ray said. “I thought, ‘Nah, I’ll just shoot myself now.’”

Instead, Ray tooled around after graduation, at first accepting a teaching job in Vermont.

“I didn’t find Vermont as friendly,” Ray said. “Winter was interminable. Spring sucked. There was a very long mud season, followed by a protracted fly season, and then there was summer. It was tough... I had trouble making friends.”

So he returned to Massachusetts. Tom was still around, for one thing.

“He was constantly trying to lure me back,” Ray said.

“By the way, I should mention that hardly anyone knows how to turn an odometer forward,” Ray told a caller named Rick, whose girlfriend’s car had recently come back from the shop with 20,000 more miles on it than when it was dropped off. “There are plenty of people who can turn it backward, but forward is a lost art.”

“The whole thing’s gone screw-y,” Rick said, explaining that the increase in mileage on the odometer was accelerating.

“She needs a speedometer head,” Ray says, adding that a dealer could put the correct mileage on it, though there were other options. “I don’t know what the rules are in Connecticut, but if you’re in New Jersey or some place like that...”

Tom interjects to finish his sentence.

“...you can put anything on it! You can get it done in the supermarket parking lot!”

“Would you consider making a trip to New Jersey?” Ray says.

“It’s not that far,” Tom says.

“It’s only about 20,000 miles for you,” Ray says.

Ray and Tom started Hackers Haven in 1973 in Cambridge, a business which eventually turned into the Good News Garage, which still exists. Ray was a regular for decades. The early years of the shop were rough-and-tumble.

Ray and Tom first owned Hackers Haven with another guy, but that relationship broke down after sometime, and one day that other guy brought some dogs to the shop and ordered everybody out. When a friend of Ray’s who was living there came to retrieve some school materials, he wrapped his arms with towels—“so he looks like the Michelin man,” Ray said. That and he carried a baseball bat for protection against the dogs, successfully getting his stuff. That friend, Ray said, later went on to become a rocket scientist of some repute.

Other customers back then included the astronaut John M. Grunsfeld, who also later went on Car Talk as a caller from space.

“Around 1977, I used to have this green Sunbeam Alpine,” Grunsfeld once said, “and I would pay a few bucks an hour and some folks would help me fix it. I think they sound kind of familiar.”

Car Talk started in Boston in 1977 on local radio. Ray and Tom would also do segments on NPR’s All Things Considered. Later, Susan Stamberg, a host of All Things Considered, helped convince NPR execs to let them do their own show.

From The New York Times’ obituary for Tom in 2014:

Ms. Stamberg recalled how hard it had been to sell NPR executives on the idea of building a radio program around two mechanics talking about cars. But cars, she said, were beside the point: “What I loved was the relationship between them.”

Early on she would mention the garage as part of their introduction until they told her, “Stop using the name, we can’t handle the traffic,” Ms. Stamberg said.

The first Car Talk to air nationally was broadcast on Halloween in 1987. Tom and Ray started off tentatively, and you can sense some nervousness in their voice. But what they didn’t know was that callers were screened by producers. Calls immediately poured in.

The show’s producers eventually honed a format in which callers would message on an automatic service, and at the peak some 2,000 called in weekly. The best of them would get callbacks, and a call from a producer and be put on the air with Ray and Tom.

The callers would be in an order that makes them different enough from each other. Tipping off Tom and Ray to what problems the listeners have—something which didn’t occur—was unwelcome. As Tom once said, if they knew the problems in advance they would have to do research on them, which constituted work.

But they had help, as The Boston Globe reported in 2005. During calls Doug Berman, their longtime producer, would feed them information through a headset about the car in question. That explains why in many calls there was a noticeable lag between the caller’s question, the yukking, and, at the end, the answer.

You might call this cheating, if not for the number of times Tom and Ray still got it wrong. Whatever information they got didn’t always help that much. It also, in its own way, reflected the spirit of Tom and Ray. Their approach to car repair was intensely collaborative, something that isn’t common in an industry that rewards mechanics mostly on how well they bill the most repairs, needed or not.

“They’re just machines,” Ray told The New York Times in 1988, after recently purchasing 1987 Dodge pickup. “This is not brain surgery. It falls apart, you get another one.”

All this time, Car Talk built a huge audience. Ray and Tom had a vague sense of this, but tried their best to stay oblivious.

“When we were sitting here, just us and [producer David Greene] and [producer Doug Berman] and the engineer it never came into my mind like, ‘Oh, I better do my best possible job because there are four or five million people listening,’ Ray says. “We tried to do our best anyway in whatever that was. We never went out of our way to try to be funny. We never went out of our way to try to give the right answer necessarily although we did try, but we didn’t go to extreme measures.”

“I got a stuck dipstick, honey,” one caller opened with in the early ’90s. “I’m not kidding I have put some big homeboys with Vise-Grips on this thing. It won’t budge.”

“And it won’t come out, eh?” Tom asks.

“If you want to see a man ruffle his chest up and poke it out just say, ‘Oh, my dipstick is stuck.’ Here they come,” the caller says.

Ray’s advice was to cut off the top of the dipstick with a hacksaw and “shove it in,” reasoning that you didn’t need it anyway.

Tom’s accent was basically unalloyed, but Ray told the Boston Globe a few years ago that he made an effort to pronounce his Rs for the benefit of everyone not living in the greater New England area. That allowance fit the pattern of their relationship—Tom tended to be more direct with listeners, usually walking a fascinating line between cheerful and rude, while Ray was the more helpful one, the one who actually spent time in the shop, the one who could solve problems.

“Somebody has to know the answers, and it wasn’t going to be my brother,” Ray said.

Ray has driven mostly regular cars throughout his life, including a lot of American cars but plenty of Japanese cars as well. He currently drives a 2007 Honda CR-V given to him by his daughter-in-law. Before that, he had a Pontiac station wagon, a Chevy Malibu, and a Ford LTD.

“My first car was a ‘62 Chevy Impala, 120,000 miles,” Ray said. “Which was unheard of back then... I remember running out of oil a bunch of times. It burned about as much oil as it did gas.”

Ray has little nostalgia for that era of automobile, saying that he would take a modern Nissan Versa over any car built in the ‘60s or ‘70s, thanks to modern standards of reliability and safety.

“Every year [in the ‘80s] they were making big strides,” Ray says. “Things got quieter, stingier with gas.”

In 2015, the Boston Globe took pains to catalogue the Magliozzis’ prodigious insults—all G-rated, of course. (In person, I tried a few times to bait Ray into cursing, and I think it worked once. The man simply has no use for curse words.)

Also in the “bad driver” category are a number of putdowns focused more specifically on either the falling-apart vehicle or some particular bad decisions by its operator. Stamper noted the Magliozzi brothers’ frequent usage of “idiot light” for dashboard panel warnings. They also seem to have invented the term “black tape solution” for what to do, at least maybe if you’re a jamoke, when the idiot light is flashing — i.e., cover it with black tape.

The Merriam-Webster citation files also feature Magliozzi quotes attached to a number of “babe magnet” antonyms: “heap,” “clunker,” “junker,” and “rust bucket.”

Mechanics, lawyers, and pushy husbands received some less affectionate insults: “sleazeball,” for instance (“We did use ‘sleazeball’ quite a bit, especially referring to unscrupulous repair shop owners,” Ray said) or Tom’s fake-Latin version, “Myxomycetes Spheroid,” meaning “slime ball.” “Mechanic’s shrug” is a classic “Car Talk” term for the know-nothing shuffle performed in response to question after question.

Some other Car Talk words and phrases The Boston Globe identified: “dope slap,” or a quick, corrective slap to the back of the head in punishment of stupidity; “urgent haircut,” or the need to relieve oneself; “T.S., Eliot,” or a public-radio friendly way of saying “tough shit”; “schnerdling,” a word with Icelandic origins to mean toilet; and “boat payment,” a unit of measurement arising from Ray’s discovery that the least scrupulous mechanics he knew all owned boats.

“I have kind of a capricious problem with my 1988 Volvo wagon that I bought from my ex-husband’s wife,” Penny tells Ray and Tom, though they initially missed the last detail.

“When I got the car from her,” Penny says after a moment.

“Who’s ‘her’?” Tom asks.

“Oh, I got the car from my ex-husband’s wife, his current wife,” Penny says. “I trusted it because she had all the records. I took a friend over. I met her. She seemed, she seemed like a nice person. I mean, after all. And I talk to my ex-husband regularly. He likes her. So I trusted it.”

“He liked you once too,” Tom says.

“Now mind you, he’s an attorney,” Penny says.

Penny then laid out a complicated story involving the Volvo infrequently overheating, and the brothers both agreed there was probably a blockage in her radiator, and to get the thermostat replaced.

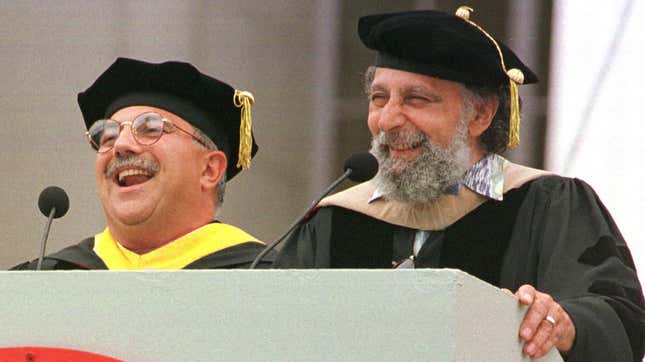

When the brothers won a Peabody Award in 1992—“Perhaps more appropriately named ‘Zen and the Art of Automobile Maintenance,’ this entertaining and informative show takes us simultaneously under the hood and into the mind of its vast listening audience,” the award citation reads—they went to the Waldorf-Astoria in New York to accept it.

“You like us! You like us!” Ray says in the beginning, an allusion to Sally Field’s Oscars speech from eight years prior.

“You know, we’re just a couple of jamokes,” Tom says.

A jamoke in Ray and Tom’s formulation is a bozo—not intended to offend, since it’s possible that a jamoke has no idea what they’re doing wrong. Someone who insists, for example, you idle your car for a half hour in winter time before driving—to properly warm up the engine or whatever—is a jamoke, since their advice is baseless but not harmful, exactly.

“They know that probably,” Ray said.

“They know that and we know nothing about radio,” Tom said at the Peabody ceremony, taking over. “In fact, you know, we got really excited and now it’s kind of a disappointment because when our producer Doug Berman called he said we won a Peabody Award. I thought he said the auto body award. It’s Peabody! Who’s Peabody?”

Ray interjects.

“I was hoping there’s be a large cash prize. I’m disappointed but I guess my brother’s brain augmentation operation will have to wait. Thank you very much. Appreciate it.”

Ray and Tom turned down an untold number of endorsement offers over the years, reasoning that wealth was useless after a certain point. Tom, especially. Per The New York Times:

He was the first in his family to attend college, NPR reported, earning a degree in economics, politics and engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1958. His brother graduated from M.I.T. in 1972.

[...]

He described the incident in 1999, when the brothers shared a commencement speech at their alma mater. Tom described driving on Route 128 to his job in Foxboro, Mass., in a little MG that “weighed about 50 pounds” when a semi-truck cut him off. Afterward, he thought about how pathetic it would have been if he had died having “spent all my life, that I can remember at least, going to this job, living a life of quiet desperation.”

“So I pulled up into the parking lot, walked to my boss’s office and quit on the spot.”

The thing about the Puzzler, the segment that was frequently not car-related but often a plain brain-teaser, was that it started it as a ploy to get more business to their shop. The show wasn’t national in the late ’70s, and WBUR wouldn’t let them mention their shop on air. So a handy workaround was having a feature that gave out the address of the shop for listeners to send answers into, but without naming it.

“We took the gig even though it didn’t pay us because we thought it would be good for business at the garage but they wouldn’t let us do that, the bastards!” Ray said. “Pretty soon people made the connection.”

The show itself quickly created awkward scenarios though, in which people would drive their beaters from long distances, expecting the Car Talk guys to do their thing. It didn’t always pan out. Some were starstruck.

“One particular guy came down from the far reaches of Maine near the Canadian border,” Ray said. “I didn’t even know they have radios up there. And he had listened to the show—this is when we were on nationally—for a number of years and he had some oddball problem where the car would cut out periodically without any warning. He had taken it to everyone within about a 100-mile radius. So he decided, I’m going to make the trek. So he gets a room at the Hotel 7 or whatever, drives himself down here and we had the car for a day or so, and I’m not sure we figured it out for him, but he was—I don’t know exactly what the right word is—jittery when he left. He backed his car out of the garage—he was attempting to back his car out of the garage—and crashed into the wall.”

The worst part of life is saying goodbye. Goodbye to people you love. Goodbye to people you have loved. Goodbye to your family. My own brother is still alive, but we haven’t spoken in years. We never said goodbye, but we might as well have. Most goodbyes are like that. Things rarely just stop. Things mostly drift.

Until the long goodbye comes. When that happens, you’re never ready. When that happens, it happens very, very quickly, and then, almost as quickly, the moment is gone. You adapt. It was just yesterday we were joking around, like we used to do, you think. Now, you’re gone.

Ray knows this. It was just yesterday that he and Tom were in the studio yukking it up. It was just yesterday when they opened their shop. It was just yesterday when Ray was a child and Tom was in college, taking Ray places. It was just yesterday when Tom was still alive.

“I’m sad that my brother’s gone, obviously, but we had a great, great, great time together,” Ray said. “I say that without any equivocation. Even when we weren’t [in the studio], we were together all the time. We did stuff and we had a million laughs, and nothing was more fun than sitting at the dinner table with our folks and kids. It was great! Most people don’t have that in their lives. We just had a fabulous time. Do I feel cheated? I don’t. There were many, many, many years. And what I have is looking back on all those great Christmases, birthday parties, and backyard barbecues, and all those kinds of things that we did together that were just so much fun.

“And all the stupid stuff,” Ray said.

(Update, 5:42 p.m.: A Car Talk producer emailed to assure listeners that The Best of Car Talk is still distributed by NPR to some 80 stations, after many stations expressed interest in continuing the show following the previous announcement. I’ve updated the post.)