If there was even a shred of hope for my objectivity, it was gone as soon as I climbed inside the 2019 Lada Niva, slammed its startlingly thin door shut, and felt the 84 horsepower engine rumble to life. Releasing the clutch, I heard the familiar ghost-like howl of the gearbox. Derived sometime in the 1960s from Communist-leaning Fiat engineers, it burrowed deep into my soul.

That howl is the unmistakable sound of a classic Lada—the same sound that punctuated my visits to Russia as a small child. The same sound was there during my parents’ adolescence, my grandparents’ mid-life and my great-grandparents’ Golden Years.

And as I switched from second to third gear, the howl grew even louder. I knew it was going to be an emotional week.

(Full disclosure: Lada lent me a “4x4" aka Niva for a week with a tank of gas, making one of my longest-held dreams come true.)

A Cult Icon Among Cult Icons

Fortunately, objectivity is useless in this case, because the Niva commands a cult-like reverence. Like certain bad movies, junk foods, or renegade religious groups, cult cars like the Niva endure because their followers overlook, or even embrace, gaping flaws.

The Citroën 2CV, for instance, had an engine with perhaps two cylinders, and a top speed of three mph. It was technologically rooted in the 1930s, yet it survived until 1990. And this is probably because it embodied a distinct sort of Frenchness that can’t be found even in the moldiest of cheeses.

The same can be said about America’s beloved Ford Crown Victoria. It was a simple, understated, and easy-to-repair sedan. (Read: It wasn’t the best car, but it was body-on-frame so it was more than a little difficult to total.) And it had this air of pre-Oil Crisis America about it. It valiantly served taxi drivers, senior citizens, wannabe cops, actual cops and municipal clerks across the 50 states for decades. Never mind that the Crown Vic was too thirsty and outdated even by late 20th century standards, it lasted until 2012.

As backwards as it seems, the Lada Niva continues to survive. It has this enduring charm as a cheap but capable off-roader. On its stock narrow tires, it’ll ferry you effortlessly across the worst terrain imaginable—to places that’ll send Jeeps with angry headlights running for the JCPenny parking lots where they belong. And it has done this sort of thing for 42 years across all seven continents (including Antarctica). Needless to say, the world has taken notice.

But, like all cult icons, the Niva forces you to make compromises. Yes, when the nukes start flying, the Niva is the only car you’ll need. But, when you’re on smooth, higher speed roads or—God bless you—expressways, the Niva guarantees the bare minimum of comfort and safety.

What is it?

Officially, this car is called the Lada “4x4.” But this isn’t fooling anyone.

Before you get confused, realize that this is a Niva. It’s same Niva that was once the world’s premiere unibody off-roader. The same Niva that was born in 1977 in the USSR and the same Niva with this face:

So, to be clear, when the Niva nameplate was handed off in a joint-venture with General Motors in 2006, the replacement name, “4x4,” was meaningless. No one has and no one will call this thing the “four by four.”

Since its debut in the late ‘70s, the Niva has undergone at least some changes. It started out sharing many parts with the Lada 2106 sedan. Later, it got some bigger and smaller engines. Then the suspension changed. Then, the Soviet Union collapsed. Then it got fuel injection. Then the interior changed. But looking at the thing now, decades after the design’s debut, there’s not a ton that distances the 1977 original from this, the 2019 Niva.

What Hasn’t Changed

Jason Torchinsky wrote a review about a 2010 Niva a few years back. Having personally driven this 2019 model and reading Jason’s review, it sounds like not much has changed in the past decade.

Still, I figured that Jalopnik likes a roughly once-per-decade-check-up on the Lada Niva. And I have a feeling that we’ll be due for another. See you again in 2030.

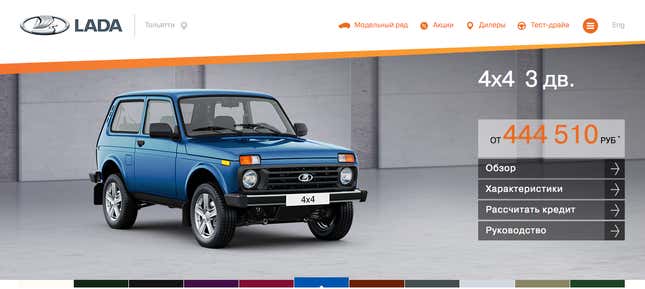

In any case, the standard, three-door Niva is still extremely affordable. In Russia, it’ll set you back $6,834 (or 444,510 rubles). For that money, you get an 84 horsepower four cylinder engine (and if you’ve ever driven a Niva, it’s more than enough power) that’s mated to a five-speed manual transmission. Obviously, there’s full-time four-wheel drive, high/low-range gearing, and differential locks come standard.

We’re talking about a genuine off-road vehicle that can allegedly go almost 90 mph. It has seats and windows and a roof. And it costs as much as a high-end sofa.

On the inside, the Niva is still the same analog oasis it was in 2010, 2000, 1990, and so on. Mechanical knobs and switches and levers are seemingly everywhere, disrupted solely by a 2-Fast-2-Furious-era Pioneer stereo. There are no soft edges. And there are no shitty, plasticky attempts at “styling” in the form of swooshes. It’s all unashamedly quadrilateral.

To my delight, lots of the trim pieces match the ones found in my 1981 Lada 2101 (the first ever Lada model). This includes the headliner, the visors, the left-hand ignition switch, the indicator stalks, and those woeful, perpetually-jammed slidey-sticks that control air temperature.

What’s Changed

The Niva has endured a few changes in recent years. Chief among which is optional air-conditioning. But you’d never guess because the AC controls are masterfully blended among dark, notchy switches of tremendous heft. And when you press them, you get a feeling that something, somewhere has launched.

Also, the Niva now comes with cupholders and, frankly, they left me speechless.

When the lever below is in “high range” (or, in other words, where it’s meant to be 99 percent of the time), it physically prevents the left cupholder from doing its job.

I initially thought that this was maybe a quirk of the press car I was loaned. But I checked out three other Nivas at two different dealerships, and all had the same interesting “feature.”

So, if you want to use your left cupholder, put the car in “low range.” Otherwise, fuck you.

The more I think about how something like this could have been produced on an industrial scale, the more confused I get. But, for some reason, this made me love the Niva even more.

How Does It Drive?

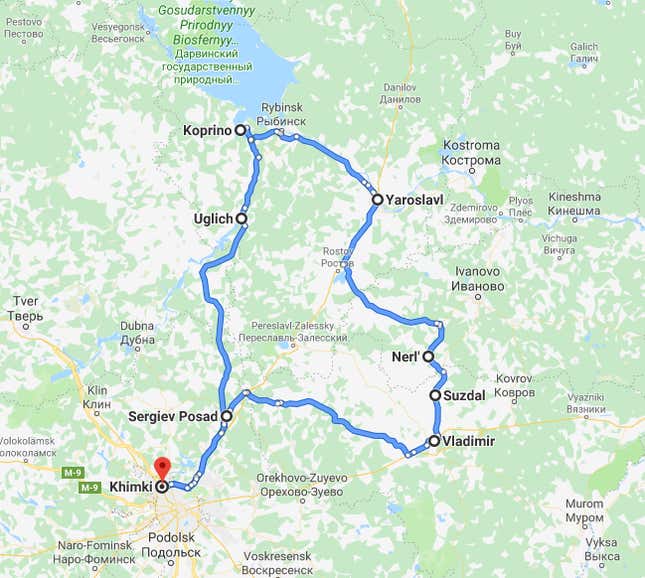

I had the distinct privilege of driving a Niva for a week in Russia, of all places. So I took a 960 kilometer (600 mile) drive across what’s called the Golden Circle. It’s a string of magnificent ancient cities to the north and east of Moscow, teeming with cathedrals, kremlins (fortresses), and other historically important places. The roads I took along the route varied from high-speed expressways to gravel paths to cobblestone byways along the Volga river.

What’s Great

On all these different road types, the Niva had distinct pluses and minuses. But on absolutely awful surfaces, the Niva was like a Lamborghini Aventador winding down the Amalfi Coast. It was a ‘50s Austin Healey puttering along a narrow country lane somewhere in Wales, or a mid-2000s BMW 3 Series careening down the New Jersey turnpike, passing on the right with no turn signal. That is, a perfect pairing a vehicle and place. Total bliss. Synergy. Destiny.

I learned this somewhere between the ancient cities of Suzdal’ and Yaroslavl’. My GPS suggested a trip that was allegedly 15 minutes faster than the route I was already on. Keen on turning off the fast-paced federal road I’d been driving on, I gladly accepted route change.

Turned out, this “shortcut” was barely visible on the map. And nobody else was going that way. But I was in a Niva. So I pridefully plowed on.

One empty road led to another that, frankly, wasn’t. And I found myself on the seemingly abandoned remains of a betonka: a rudimentary, Soviet-era road built out of concrete blocks.

Over time, the seams widen and holes form between the blocks. So there was a medium-to-severe bump every four feet. It felt like driving down a particularly long set of stairs—a constant du-DUH-du-duh-du-DUH-du-duh.

But, on this particular “road,” I started driving pretty fast.

I leaned forward as far as I could, eyes wide, biceps fully flexed, forearms pulsating, slam-shifting the gears and mushing the pedals and thrashing the steering wheel from side to side—weaving between the potholes, entire bricks, and fallen trees that dotted the road. For some reason, the gargantuan steering wheel and the far-away shifter felt right in this scenario.

This, I learned, was the proper Niva driving position. I was calm. Razor focused, teeming with adrenalin, sure, but otherwise calm.

At no point did I question the Niva’s ability to proceed. It read imperfections in the road like a book. The thin tires hopped over-and-across bumps rather than in-and-out. And even if I managed to slam the car deep into a crater at 50 mph, the Niva didn’t seem to care. It just sort of wobbled itself back together.

In The Muck

While the betonka had at least some semblance of roadway, later in the week I found myself truly off-road. I was about an hour away from the city of Rybinsk when I decided to drive into the forest, just to see what I could find.

It was very picturesque and flat at first. I looked for mushrooms for a while, as Russians do.

But then came the mud.

As far as understanding anything about off-roading, I am an utter moron. But that’s exactly what made the Niva ideal. It was like it was made for someone like me.

Yes, you have a sequence of knobs and levers that control things like “differential blockers” and “gear ratios.” But, so long as you aren’t crossing an active mudslide, you don’t need to know what any of it really does—the same way you don’t need to know how a microwave works when you reheat mashed potatoes.

When you’re off-road in a Niva, everything is instinctual. Use the car like you would a simple tool, like a hammer or a sponge.

If you want to, put it in “low range,” which, at the very least, frees up your left cupholder. Or don’t. All you really need to do is plan your escape route, aim the car, and push the accelerator. And the Niva digs itself out of the muck. If you can operate a manual transmission on a basic level, you can drive the Niva through hell and back.

What’s Weak

If there’s anything truly weak about the Niva, it’s that it cannot adjust to a changing world.

Particularly in the former Eastern Bloc, traffic is getting faster, bigger, and denser. And the Niva is undoubtedly confused by all this change.

On smooth highways, the white noise of the suspension smoothing out bumps goes away, and you start listening to the car itself. The engine is loud. The transmission is loud. The blower motor is loud. There’s always some sort of squeaking.

You have nowhere to rest your elbows and knees while cruising. And when you pull over to take a small break from all the racket, the car shakes at idle.

What felt strangely ergonomic on rough roads feels ridiculous on smooth tarmac. That enormous steering wheel, you’ll find, is unadjustable. And the shifter is indeed a bit far away.

If you decide that it’s safe to accelerate above 70 mph, you’ll once again find yourself in that Niva driving position—leaning forward, eyes wide, forearms pulsating—but, this time, for all the wrong reasons.

In highway-speed scenarios, you have to be perpetually defensive. With its narrow tires and short wheelbase, the Niva will not corner predictably. Obviously, there’s no advance collision warning, blind spot detection, or airbags that’ll help you if the unspeakable happens.

I’m being brutally honest here because the Niva was brutally honest with me.

It wasn’t designed to be driven long distances at high speeds. It was never meant to contend with speeding BMW X6s, Subaru Outbacks, and Volvo trucks on divided expressways. And it doesn’t give you any indication that it wants to be.

So in a way, it’s unfair to label the Niva’s awfulness on the highway as weakness. It’d be like faulting a whisk for working poorly as a spoon.

Verdict

Think of the Lada Niva as a transaction. Like going to the DMV, but in a nice way. You know what you want, and the Niva knows what it can provide. But asking anything extra of the Niva would be like asking the person who hands out your driver’s license for a massage.

If you buy a Niva primarily for use on the highway, you must be wearing an aluminum foil hat. You buy a Niva to go somewhere deep in the forest. It’s meant to be used, to quote a weird Russian saying, “where wolves are afraid to shit.”

And there are still plenty of places in the world where paved roads are few and far between. Where off-roading is less a hobby, but more a reality of getting from A to B. That’s precisely where the Niva’s rugged simplicity counts the most. It’s what makes it a legend the world over, from the European Alps, to the dunes of North Africa, to the deepest snowbanks of Siberia.

See, my opinions really don’t matter this time. The Niva knows exactly what it can and cannot do; and it doesn’t pretend to be anything that it isn’t. So if I whine about noise, or safety, or ergonomics, or not being able to put a soft drink into a plastic hole in the center console, those who actually need a Niva could care less. It’s all trivial.

I asked some of the Lada reps about the Niva’s future. I wanted to know if there were rumors floating about its discontinuation. But all they could tell me was that the Nivas fly off the lot. And it probably isn’t because of the cupholders.