For most Soviet citizens, buying a new car was financially impossible. To put things in perspective, Alexander Petrovych (who built one of the cars you’ll see here) made a monthly salary of 140 rubles in the 1970s. At the time, a new Lada cost 6,030 rubles. So, if Alexander really wanted a Lada, he would need to starve his family of four and live without electricity for roughly 43 months.

For a resourceful and talented few, homebuilding a car was a cheaper option, but not by a lot. When Alexander Petrovych’s mother passed, she left him an inheritance of 600 rubles—500 of which went to the engine and transmission for one his projects, the rest paid for the gravestone.

It was Petrovych who homebuilt one of the cars in the collection of the man I met named Yura. In his free time, Yura collects homemade cars from the Soviet and early Post-Soviet era. And while this may sound very niche—like a collection of hairnets or canned vegetables—this category of vehicle couldn’t be any more broad.

The core materials needed for car building—the plastics, the metals, the knobs, the rubbers—were not typically easy to come across in those days. That and access to these materials was anything but equal. Some homemade car builders worked at big factories, with backdoor access to machine tools and the ability to steal glue. Others had little more than a store-bought toolkit, and perhaps a wire brush.

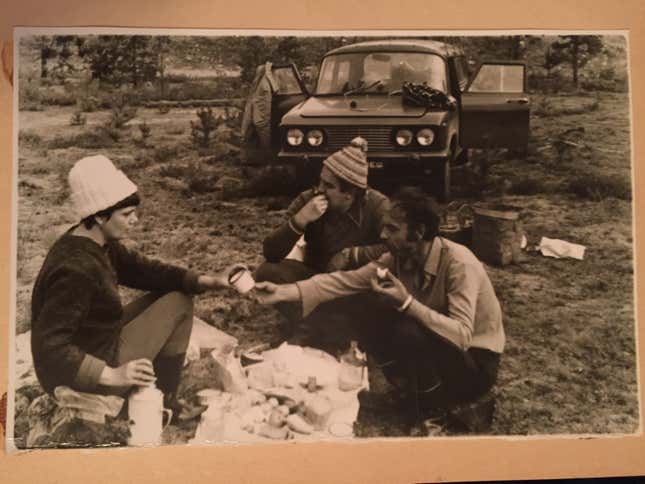

Resources aside, each homemade car is an incarnation of the creator’s automotive dreams, whatever they may have been—air scoops and spoilers and three-figure top speeds, morning commutes not on the dinky trolleybus, family mushroom picking trips deep into the woods.

Like the $19 million Bugatti La Voiture Noir, these cars are one-offs. But the La Voiture Noir is almost destined to endure a solemn existence, probably hidden for most of its life in a Swiss cave, languishing alongside various other supercars, some valuable art, and the Large Hadron Collider. The homemade cars of the Soviet Era were built to be driven, and driven often. (That’s primarily because those who built them had nothing else to drive.)

In keeping with tradition, Yura drives the cars in his collection often. Never mind that each one presents a unique assortment of mechanical treacheries. Pay no mind to the door hinges lifted from a wooden reach-in closet. Don’t stress about the fuel tank placement that puts the Ford Pinto on the cutting-edge of vehicle safety.

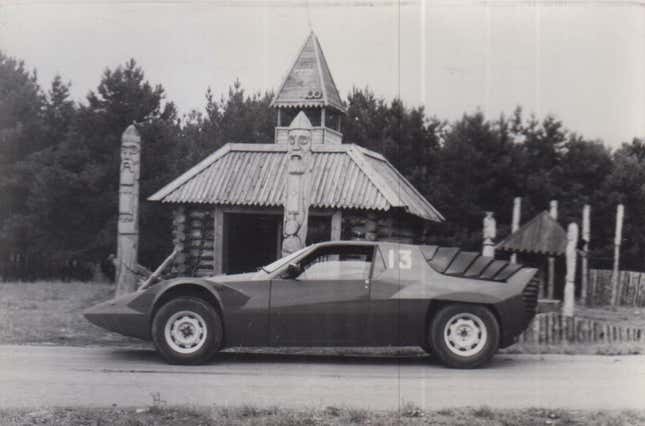

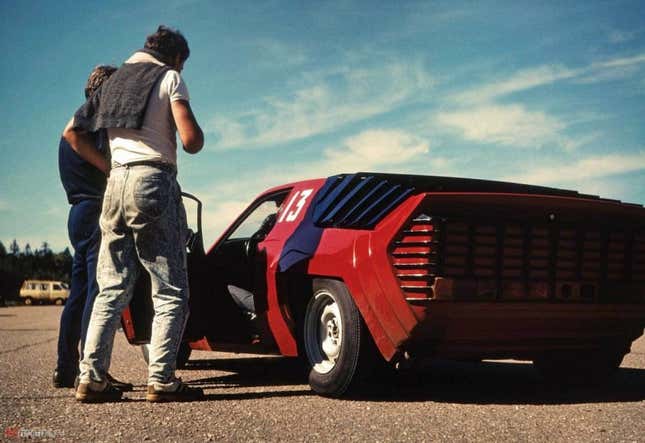

Yura’s first acquisition was built in the early 1990s by Evgeniy Titsev, а late Soviet water skiing champion who relentlessly dreamed of Porsche 911s. Yura dubs it the LamborZhiga—“Zhiga” being short for the iconic Lada/Zhiguli Sedan. But the car is, ostensibly, Porsche 911-inspired.

Well, perhaps it’s a bit Lancia Stratos-ish. It’s based on a Lada anyway, making it a cousin of Fiat, and therefore a second-cousin-twice-removed of Lancia. Nonetheless, Yura contends—perhaps not to offend the creator—that “it sort of looks like a 911 from the rear, if you’ve had a drink.”

It has a spoiler, as well as bucket seats and a rally-style seating position. Is it a performance car? Absolutely not. Sitting on a 60-horsepower Lada 2101 drivetrain, the car was never meant to perform in a motorsports sense. But it’s a performance piece nonetheless.

Imagine: It’s the early 1990s. You’re walking along a gray urban expanse somewhere in the recently collapsed Soviet Union. You’re wearing a hat. The only traffic you see is trams, bumbling Moskviches, and, if you’re a bit lucky, a late-model Volga. Then, out of nowhere, this winged, canary-yellow machine emerges on the concrete horizon. Is it a car? Is this NATO?

Anyway, Yura flew to Sochi with his girlfriend, bought the car, and embarked on the 1,500-mile journey back to Saint Petersburg. “It’s basically a Lada underneath so I thought I’d be fine to drive it back all the way” Yura said, recalling the trip. Sure. What could possibly have gone wrong? After all, this is that car with the door hinges lifted from a closet.

Since the Car Gods are boundlessly merciful, Yura and his girlfriend made it home safely, the LamborZhiga (and hopefully their relationship) intact.

Along the way, they broke down five times. Now, five breakdowns may not seem that big a deal given the circumstances. But when it comes to repairing a car built decades ago by a Russian man with a bucket of epoxy and a hammer, there are no subreddits. There are no no “lemme get, uhh…” phone calls to the Russian equivalent of AutoZone. There are certainly no shaky-camera, mouth-breathing YouTube vloggers who can help you.

A few months later, Yura found what would become the crown jewel of his homemade car collection—the Virus.

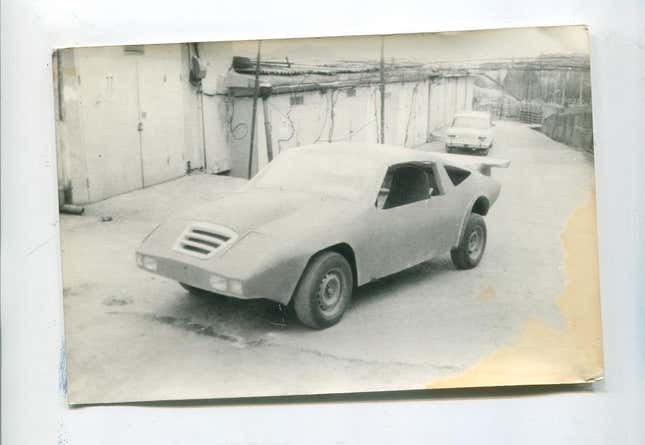

The Virus was built over the course of twelve years by Valentin Samoilov, a firefighter from the Volgograd region. The car is formed by riveted sheets of steel, titanium, and aluminum-alloy. The resulting body lines are meticulous and undeniably cool.

In the Soviet Era, homemade cars had to meet arbitrary vehicle safety regulations. These regulations governed things like power-to-weight ratios and wheelbase dimensions. And, according to Yura, the Virus “broke all of these rules.”

Unlike Yura’s other cars, the Virus has genuine motorsports ambitions. It sports a front-mounted 2.4 liter inline-four lifted from the USSR’s flagship Volga sedan, modded with dual carburetors and a hand-built exhaust system. The rear suspension system is entirely custom built. It has near 50:50 weight distribution, seats four, and apparently sounds like a gurgling American V8 (as was Samoilov’s intention with the custom exhaust system).

The Virus sat idle for decades, and is now in rough but restorable shape. The coming restoration will be difficult but interesting, given that all the custom-fabricated parts and panels exist in only one example.

Yura had to pick up the Virus in Volgograd, a mere 1,050 mile trip from Saint Petersburg. Naturally, Yura did the reasonable thing: He rigged a trailer to the LamborZhiga, drove to Volgograd, hitched up the Virus, and drove back.

Yura remarked that this trip was “unpleasant” because the already questionably balanced LamborZhiga, sporting a 1.2 liter engine from a Lada with a blown head gasket, isn’t ideal for towing. It’s fair to say that this time the Car Gods’ mercy was overextended. Yura’s rig jackknifed somewhere between Volgograd and Saint Petersburg.

Luckily, no one was hurt, and the cars sustained very minimal damage. Eventually, Yura and his Virus did make it back to Saint Petersburg.

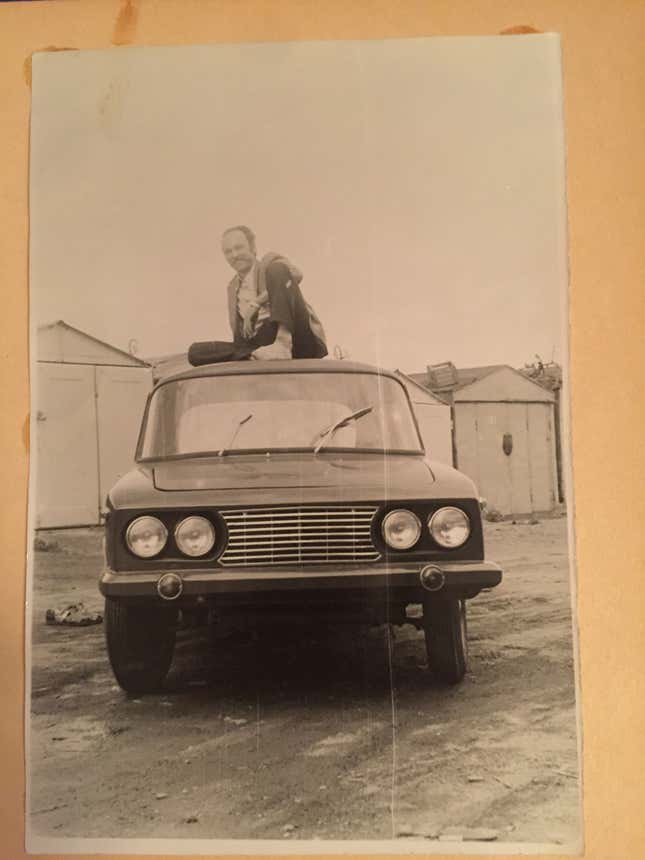

At a glance, the third addition to Yura’s homemade car collection looks relatively subdued. There’s no giant wing, and certainly no DeTomaso-style body lines. Remember Alexander Petrovych? This is his fourth and final car.

It just sort of looks like slightly askew Lada sedan. Hence, Yura has dubbed it the Faux Lada.

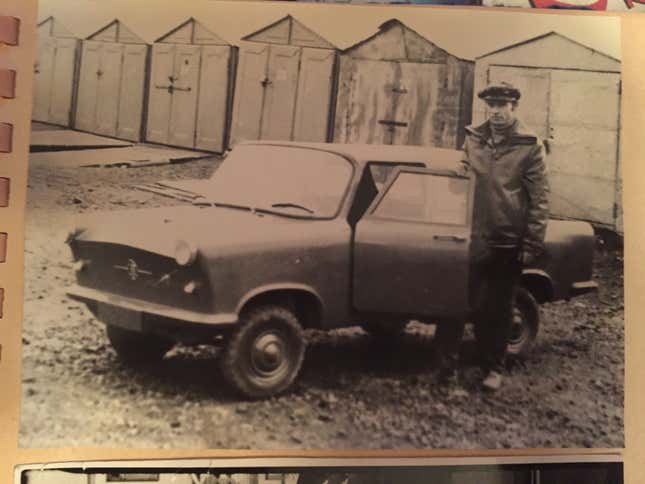

Alexander Petrovych began his car building career with a tiny, motorcycle-engined cabriolet.

A cabriolet in the Soviet Union in the 1970s was a bold move, but not exactly practical. Alexander Petrovych eventually moved on to building hardtop sedans, citing the unpredictable and wet climate of Saint Petersburg.

Ultimately, Alexander Petrovych settled on bigger, Lada-shaped sedans. His first build of this type was powered by an air-cooled V4 from a ZAZ 965. That explains the requisite air scoops in the rear, which Russians refer to affectionately as “ears.”

His second four-door sedan, which Yura now owns, is powered by a Lada engine and is therefore water-cooled. Surprisingly, this engine is placed in the rear. (The classic Lada has its engine in the front, and is basically a Fiat in xtratufs.)

Petrovych’s Faux-Lada has its radiator mounted in the front—Porsche 996 style—which is pretty complicated engineering for a homemade car.

The Faux-Lada is built out of fiberglass, an ingredient of choice for Soviet automotive homebrewers. But don’t start picturing Corvettes or Le Mans Porsches with bodies so thin you could read through them. Honestly, relegate any and all motorsports associations you may have here with “fiberglass” to Ronald Reagan’s Ash Heap of History. Instead, familiarize yourself with the Russian term Прочность (pronounced “Proch-nost’”).

Prochnost’ denotes the strength and durability of something. Prochnost’ was Alexander Petrovych’s guiding philosophy. Which is why the Faux-Lada is made from five layers of fiberglass held together by bucketfuls of resin glue. Alexander Petrovych glued this meteor-proof body onto a wooden subframe, resulting in an essentially monocoque vehicle weighing 700 pounds more than a standard Lada 2101 sedan. Because прочность.

Yura told me that he developed this itch—or, what he refers to as “his ailment”—as a child. While growing up, Yura had a neighbor with a homemade car. This car transfixed Yura, leaving a permanent stain on his automotive palate. A few decades later, this stain materialized in a small, but growing collection of homemade cars.

Yura admits that now is the last to chance to “have some fun” with these cars “before they all end up in a museum.” But that’s a pretty optimistic view of the situation.

Truth is, many Soviet Era homemade cars lack a discernible market value. And, in terms of you’d call “historical value” or “collectability” or whatever, things are even more opaque. Some homemade cars, like the Virus, are well-documented and have at least some clout. Others, like the LamborZhiga, are more obscure. Moreover, given what Yura paid for some of these cars, they could have easily been parted out for whatever Lada or Volga bits are inside—which could very well occur when it isn’t someone like Yura who’s clicking on those ads.

Even in the Soviet Era, it was very difficult, if not impossible, to sell a homemade car. Alexander Petrovych admits in a Russian-language interview with Yura that he was forced to throw his early cars “in the garbage.” And it isn’t that Alexander Petrovych wasn’t sentimental; he just had no other options at the time. This side of their history makes homemade cars from the Soviet Era an even greater rarity today.

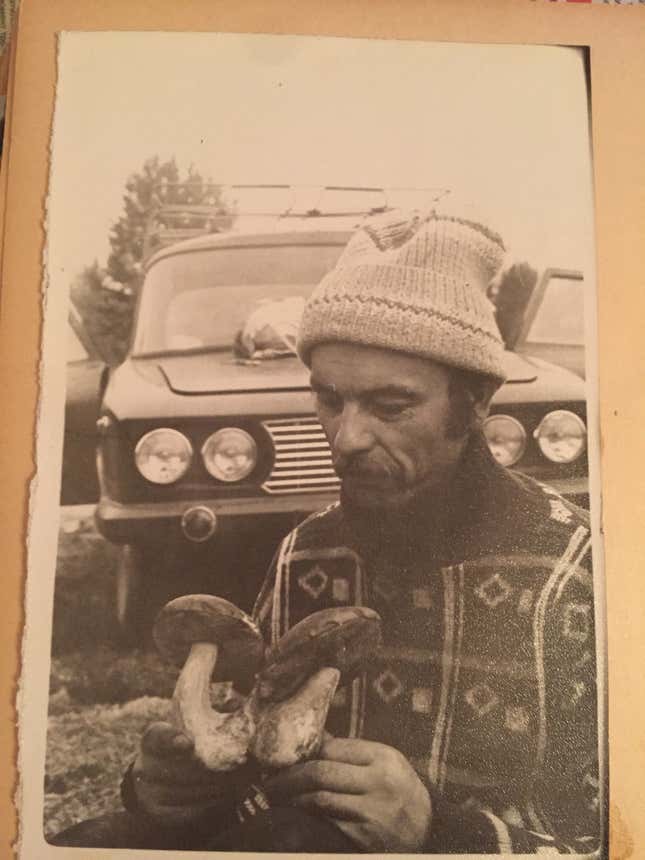

It is impossible to disentangle these cars from their creators, the personalities of whom can be found in all the panel gaps, elegantly misshapen fenders, and ingenious fabrications that make them whole. This is why Yura tries to connect with the people who built his cars. Yura invites Alexander Petrovych, who stopped driving years ago, on cruises through Saint Petersburg in the Faux Lada. In turn, Alexander Petrovych invites Yura and his girlfriend to his home, and indulges them in mushroom soup and dusty, black-and-white photo albums—brimming with snippets of his car building career and, yes, all those mushroom picking trips.