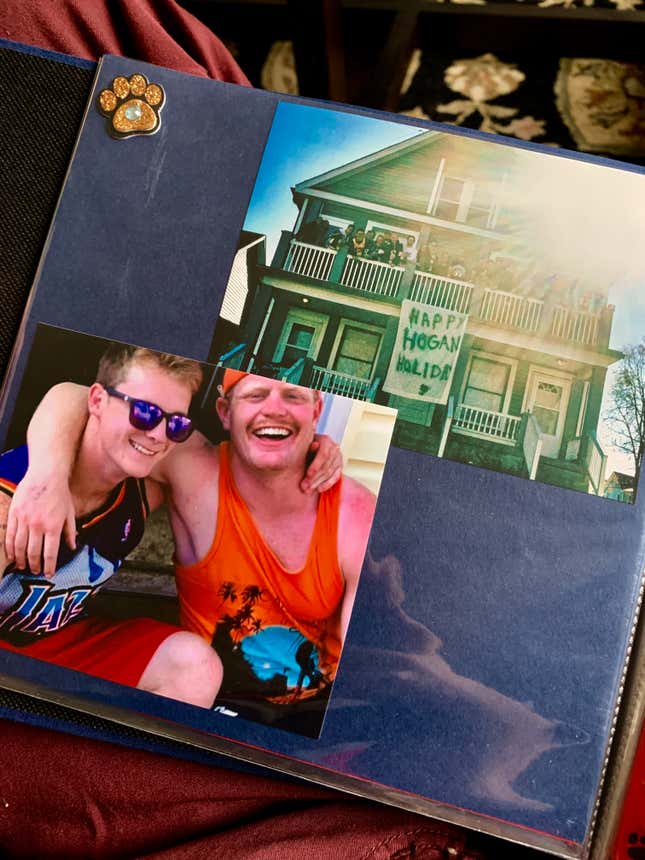

My brother isn’t just a dead man. He may not be around anymore, but it’s important to know that there’s more to Kevin James Hogan’s story than just his death.

(Full disclosure: I didn’t really know where in Ireland I was going to go, but I knew I couldn’t do this story without a lot of driving. Volvo provided an XC40 for me, gassed up and waiting at Dublin airport.)

Three years ago, my brother killed himself. A week later, I was back in class and most of the people around me didn’t even know. When summer rolled around, we went to Ireland, where my family hails from. My mom had always wanted to take the family—myself, my sister Laura and Kev—there. She thought it would be a good idea to finally go together.

Laura’s then-boyfriend/now fiancée came, too. If there’s anything we’d learned, it’s that life was too short to wait much longer. We stayed on Achill, a remote island off the country’s western coast. We spread Kev’s ashes off of a cliffside and into the ocean.

The family was still reeling. Really, for the first two years, I was trying to make sure my parents could function and keep moving. My grief was minuscule by comparison; I just wanted to help. In doing so, I thought I’d heal myself. But going to Ireland that first time didn’t get me closer to any sort of closure.

So I decided that I had to go back.

Kev never made it to Ireland. Kev didn’t really care all too much about driving. Kev didn’t listen to the same music as me.

But out here, on the winding roads that snake through Achill Island, I’m more convinced than ever that this place, this time, this car, and these songs will help me attempt to make sense of something that I’ll likely never fully understand. A road trip to sort things out, I suppose.

I park the car on the same cliffside road we came down those two years ago; my first time in Ireland, 10 months after Kev’s death.

Zac Brown is singing “Bittersweet” as the wind rocks my car, so I let him finish.

“It’s Bittersweet, you see / You’re not here but I can feel you / Every memory is on the tip of my tongue / Close my eyes, see your face, hold on tight to yesterday / Praying when I wake, it was just a dream / It’s bittersweet.”

I trek through the same 300 yards of Irish-green grass and sheep shit that we hiked through on that breezy August day. The dark gray ashes speckled into a crashing white foam that took him away from us for good.

The first time I stood here—after we had sent Kev off—I was struck by the weight of it all. Going into that vacation, I wanted an escape from the grief and cloudiness that seeped into every aspect of my life. But between the freckles on his face, the red tinge in his hair during the summer and the “Irish Celebration” he’d play while he showered, it’s hard to disconnect Kev from our ancestral homeland. I should have known that going in.

That’s why I’m here, standing on rock thousands of miles from anywhere Kev ever went, using some boulder on the Atlantic coast as the starting point for my journey. Somewhere in these waves are the ashes that once made up Kevin Hogan. Somewhere in this country, I hope there’s closure.

I’m writing this story in large part because I have to. When Kev killed himself, he also killed any sense of nuance about who he was as a person.

Gone was Kev the rugby player, the Dayton student. Dead was the rugby team captain, the co-founder of a secret society for his best friends from rugby and the wise-ass brother who taught me how to roast with the best of ‘em. Out went “Kev” or “Hogan,” the lovable jackass who could light up the room. In came Kevin, the guy who killed himself.

It’s like calling him by his formal name somehow sheltered people from the reality that he was gone. But when you do that, you also make him sound like some distant sad-sack of a story only worth remembering for the ending.

Maybe it’s easier for us to do that; if we pretend that he was some brooding, broken man it isn’t as terrifying. Read the book of letters compiled by other Dayton students, though, and you’ll come away with an image of Kev as a hilarious and energetic friend that would go to the mat for his people in a second.

Understanding that a man so beloved was struggling deeply is hard.

Understanding that a man so beloved would want to leave it all behind borders on impossible.

But when you’re struggling with mental health, it doesn’t let up because you have a couple of laughs with friends. It’s not something that a night out can fix. And the truth is, for all the help he gave others he never got help for himself.

That’s why, three years on, we still don’t fully understand what happened. Kev had never expressed suicidal thoughts. He hadn’t been diagnosed with any illness, hadn’t spent any time in the hospital. Sure, he had sleep problems sometimes, but he didn’t really complain. He said he was doing good. His friends thought he was, too. He hadn’t had a bad week, as far as we can tell. By all accounts, he seemed like a normal college kid who liked to make people laugh. And then he was gone.

A lot of people claim to be blindsided when this happens. Sometimes you don’t want to believe them. You think that you’ll have warning signs, that you’ll have a chance to stop it. But I didn’t. I got one phone call that I never expected, and three years later our lives are irreparably different.

We’ve tried so hard to find out what was going through his head that night. But the trail is cold; we don’t have any answers.

There are things about this that’ll always be weird. Like how I’m older now than he’ll ever be. Or how—as I’ve lost weight or changed hair over the past three years—the pictures of him stay same. They’re the same ones I’ll have when I’m 70. He won’t be in the graduation photos. The wedding photos. The baby showers and the baptisms.

There are the weird moments when I’m standing in the store and see one of the weird candies he liked but could never find. And just for a second, I think, “oh I should send him a picture.”

Little moments like that when you forget. Bigger moments where you suddenly, and for no particular reason, remember.

Or the idea that more people will read this article than Kev met his entire life. For the world at large, this is the only experience they’ll ever have with him. There’s a weight on me, then, to make it something real.

I’m trying to be better. To live my life honestly, living the way he never got to. That’s why this story is set in Ireland, a place I went without any hotels booked or plans laid. It’s the kind of hair-brained, impulsive adventure Kev used to talk about.

“Keep doing it big, kid.” It’s the last piece of advice he ever gave me.

It’s the spirit that led him to drive to Chicago to try out for the U.S. National Rugby Team. His friend was supposed to drive but bailed. Kev didn’t have a car at school. That didn’t stop him. He borrowed a friend’s and bee lined for tryouts.

Coming back, he told my mom that he wasn’t going to make it onto the team. By his eye, nobody at the camp was making the cut.

He wasn’t fazed. For a moment, he wasn’t hard on himself. He was proud.

“I made my mark,” he told her. “They know my name.”

I sit out on the rock for a while, whipping winds freezing my fingers as I try to thumb to the right Robert Pinsky poem.

I start to read “The City Dark” and before long I’m nearly shouting it, trying to hear myself over the crashing waves. I finish. I don’t know what to do. So I turn to leave.

That’s when I feel it slam into me. Once I face away, I have to confront the fact that I’ll never be back here again; I can’t keep coming back. Somewhere in those waves I’m trying to find something that’ll never be back in my life.

Without much warning, I’m on my knees. Maybe it’s because I haven’t really slept for 25 hours and I’m running on empty. But as I stumbled up the steep hill back toward the car, I can’t stop turning around. I don’t know what I expect to see when I look back at the waves, but it’s never there. And I’m crying in a way I haven’t in a long time; not painful, but cleansing.

I put on “Sweet Baby James” by James Taylor when I get back to the car. My mom and dad would sing it to sweet Kevin James when he was a little kid. It was supposed to be his wedding song. Instead, we played it at his funeral. I sleep for 18 hours that night.

I wake up three hours past the stated check-out time of my AirBnB, but no one’s there to notice. I point the car in the general direction of Galway and hit the road. The High Kings’ “Town I Loved So Well” from “Live In Ireland” is blasting out of the speakers.

Picking a car for this wasn’t easy. Ireland is full of delightful little backroads and tight mountain rally stages, but visions of muscly-armed heroics behind the wheel didn’t match up. I’m not that kind of driver, and this isn’t that kind of story.

I wanted something that matched my mission. Isolating, but not disengaging. Small enough for Ireland’s roads, but big enough that I can sleep in it if I found myself without a spot to crash. Plus, I needed a good stereo.

I worried the car would bore me at first, but it was ace the whole time, a friendly billy goat that cruised the motorway, slipped down twisty R roads, careened through the countryside, climbed a mountain and drove on a beach. In what feels like 20 minutes, the 60 miles of R roads are behind me and I’m pulling into my flat in Galway. I booked it three hours ago.

I had never been to Galway. Or, that’s what I thought. But the next day I headed into the town center and parked at the cathedral. I remembered parking in this lot before. A text from my mom confirms that we did visit Galway. This is unsettling.

I don’t forget a lot. But when it comes to remembering parts of the first year without Kev, there are a lot of gaps. I can’t remember much of anything about what we did the week after. I remember the funeral and the wake, but the specifics elude me. The readings, the people who read them, what the priest looked like. I remember one sentence from the eulogy that I wrote. I don’t remember a lick of the one my sister gave.

All of this makes it harder to process. It feels more distant than things that happened years before.

A few days later I’m on the Ring of Kerry. “There Were Roses,” this time by Mick Moroney, is on the stereo.

The song, an old Irish ballad that’s been covered dozens of times, memorializes two victims of religious killings during The Troubles.

“We gathered at the gravesite / On a cold and rainy day / The Minister, he closed his eyes / And for no revenge he prayed / And for those of us who knew him / From around the Ryan Road / We bowed our heads and we said a prayer / For the resting of his soul.”

Kerry is where our closest ancestors came from. They, like the majority of the Irish people, couldn’t stick it out when famine and war upturned the soil on this rocky island.

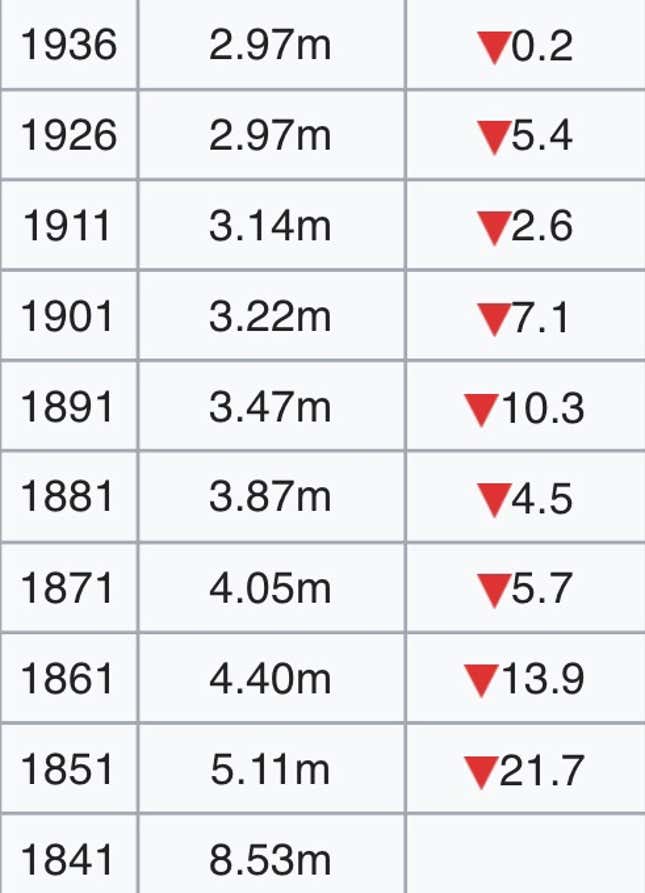

In 1841, Ireland had eight million people. By 1871, famine and resulting emigration had halved that number. When the country became independent in 1937, its citizens numbered just three million. Most of its people never got to see it set free.

Death and suffering, then, are cemented into the stony walls that line Ireland’s roadways. It’s in the waters; it’s in our blood. Our bloodline that, just two generations ago, was in Kerry.

The Galvins, they were. They were here. Dad tells me to ask around for John.

Nobody knows the name.

I go by the old hotel they used to have. It’s an empty lot on the coast.

This isn’t much of a surprise. Ask around random parts of your town and you’ll be hard pressed to find someone who knows your name. In the context of the trip, though, it’s a reminder.

A second from now, we’ll be gone. Two seconds later, nobody will remember our names. Most of what we find in life leaves with us; the rest goes with our family and loved ones.

I think a lot of people find that to be a sad thing. Some would say it’s sad that I came all the way to Ireland and didn’t find any evidence that our name lives on or any deeper connection to our ancestors.

For me, it’s freeing. We haven’t yet told our story. That doesn’t mean the story won’t be told, it means that I get to tell it. I can write something that memorializes a brother I can never save. I can travel across the world to find a closer connection to the people I still have.

I can work to be better. To get help when I need it. To make people happy. To make people feel welcome. To do what I love. To use whatever platform I’ve been given to tell stories that matter. To use driving as a way to contemplate and explore. To use music as a way to connect.

But as I settle into the driver’s seat for the next leg of my adventure—more than anything—my purpose is to keep doing it big, kid. I’m still finding out which road I’ll take, but to do right by Kev I have to do one thing. I’ll make my mark; they’ll know my name.

If you are in need of help, please reach out to someone. To a friend. To the Suicide Prevention Hotline—800-273-TALK. Hell, to me. But don’t suffer alone. The world wants you here.

Editor’s note: After concerns were raised by some readers as to whether this story could be interpreted as sponsored content—it is not, as the editorial team does not create sponsored content—we have removed some photos and amended the text after publication to erase any doubts. We regret the confusion.