For just under two decades, the roaring noise of race cars rang out from Central Texas Speedway in rural Kyle, Texas. Today, the only sounds coming from the track are that of the bulldozers.

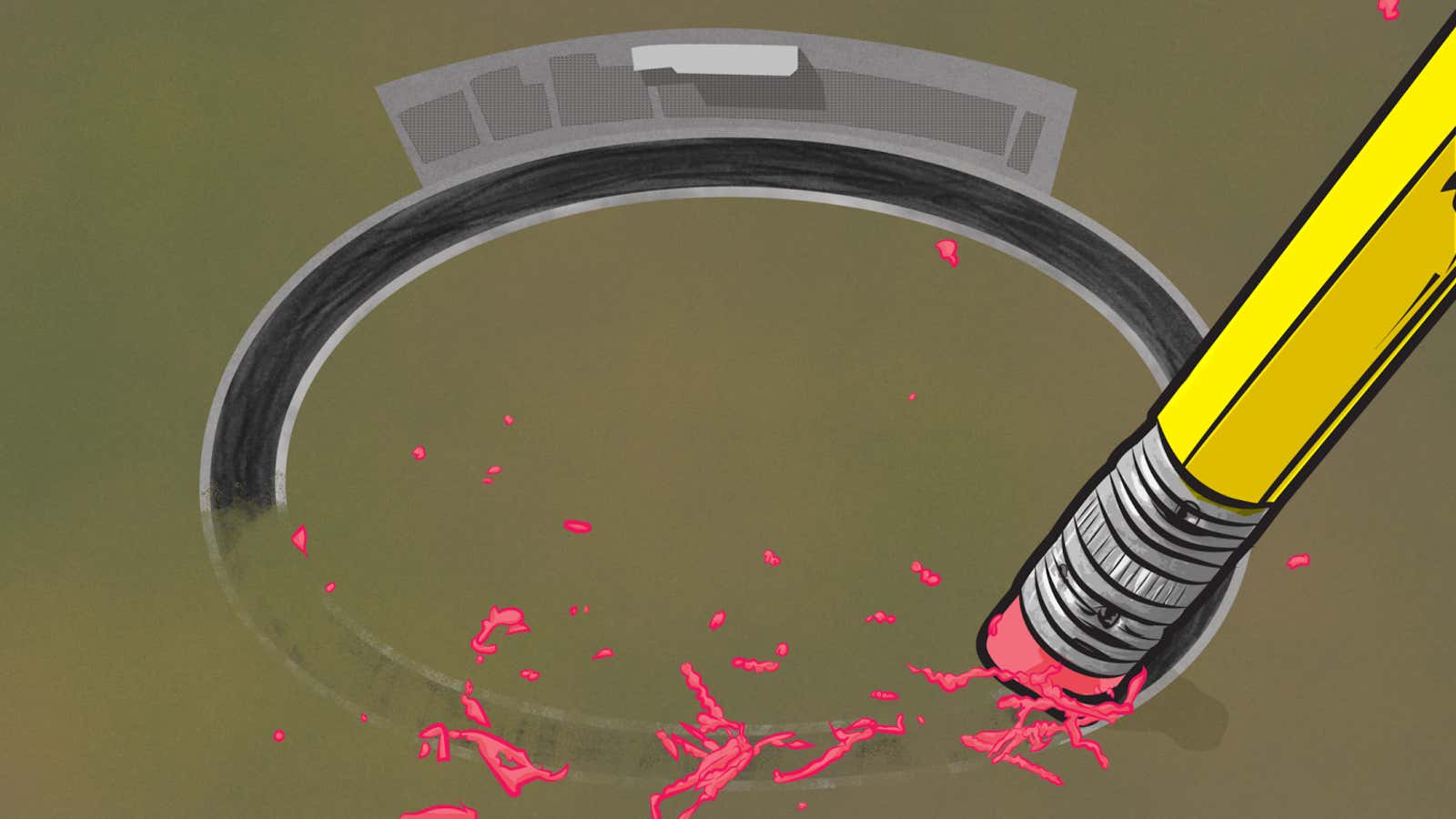

The roar was an uncommon one in Texas, as the speedway was one of the last asphalt short tracks in operation across the state. But that legacy ended after the 2016 race season—less than 20 years after the track opened, bulldozed both literally and figuratively by the same kinds of liability concerns and monetary struggles that doom different small-town race tracks across America.

Once, the future seemed bright. Things were great at the speedway, known as Thunderhill Raceway when it opened in the 1990s. Crowds were big, as noted asphalt racer Casey Smith recalled.

Thunderhill was where Smith got his first-ever Late Model win in 2001. He was barely 16 years old, unaware of how far east the crumbling asphalt scene would eventually make him travel to race. The year Thunderhill opened, 1998, was the first year Smith moved into higher-level Legend cars. In 20 years, he hasn’t forgotten opening night.

“There was standing room only,” said Smith, who was 12 years old at the time. “It was that way for a couple of years, and then it kind of fell off.”

The major leagues of American racing—both oval and on road courses—tend to run on asphalt, which makes tracks like this so integral to the racing pipeline. The choice for racers looking to start a career trajectory into the NASCAR ranks is essentially between asphalt and dirt tracks, but one is more applicable than the other: In all of NASCAR’s three top series, only one visits a dirt track. That happens once a year.

With this speedway’s closure, that pipeline is almost dry in the second-most populous state in America. What’s most surprising is how quickly it all fell, surrounded by such little clarity even from those closest to its operations.

The Better Days

The .375-mile paved oval track opened 30 minutes from downtown Austin on April 18, 1998. Though it became Central Texas Speedway during its final years, many still think of it as Thunderhill, the track that gave Texas a glimmer of hope in the ever-important and ever-declining asphalt ranks.

Smith, an Austin native who’s made a name in the South, raced at Thunderhill throughout much of his childhood. He grew up to hold his own against some of the top asphalt racers in the country—ones who grew up on the East Coast, where short tracks are close and common, not hours apart like in Texas.

Smith no longer races as regularly as he used to, though he won the 2015 Southern Super Series Super Late Model championship. That’s the same title won by now-NASCAR Xfinity Series driver Daniel Hemric in 2013. With Thunderhill’s closure and the lack of tracks in the area, Smith’s choice was to tone down his racing, or pack up and head east.

Since Smith’s family business is in Texas, he said he won’t be moving anywhere anytime soon. He’s stuck, like plenty of other racers who called Thunderhill home.

Smith said crowds at Thunderhill dwindled over the years, just as they did at other short tracks and in the highest NASCAR ranks. But despite the downfall of other asphalt tracks in the area, the fields were big and the prize money hefty at Thunderhill—at least, they were for the big events. The track’s Texas Big Shot 250, for instance, had a $100,000 total purse and paid $30,000 for the race win in November 2001, according to Motorsport.com.

“There were Late Models from all over the country [at the Big Shot],” Smith said. “That was a really cool race to run, to be able to run something that big locally.”

But while the crowds shrunk in the track’s final days, it remained healthy enough to survive. Fans and drivers still came out for the sporadic big events. Tim Self, a business owner and the father of NASCAR Camping World Truck Series driver Austin Wayne Self, took over the track lease in 2013, and tested out shifting toward entertainment and making the track into a multifunctional venue. He integrated concerts and other events into its use, gaining interest from more than just the racing crowd.

Smith remembered the time country singer Randy Rogers came out to perform at the track during the last few years of its life. Smith happened to be racing Late Models that night, and guessed around 4,000 people came to see it.

“It was cool to see it back going well again,” Smith said. “But now it’s closed. It’s kind of sad that asphalt racing is basically dead in Texas.”

What’s troubling is how abruptly the track died even though it looked like it would survive.

The Quick Collapse And The Money Behind It

Thunderhill became Central Texas Speedway when Tim Self took over. The Selfs are a Texas family, and Tim Self’s son is an Austin native. Racing updates on his website fondly refer to the track as his “home track.” But these days, it doesn’t seem like too sentimental of a reference.

It was the end of the 2016 season when Tim Self got out of the lease, early, with almost no notice and at the surprise of a lot of track regulars.

The rumors from those who worked there as well as those who just keep up with the Texas short-track scene in general were that Tim Self gave up the lease in order to fund the racing career of his son, who’s 17th in the NASCAR Camping World Truck Series and a distant 231 points behind leader Johnny Sauter’s 338 points.

Nick Holt, the administrator of an online racing forum, shared an early update about the track’s fate that said “Tim and his AM Racing folks will be exclusively focused on the NASCAR program.” Holt recalls Self saying he regretted “any inconvenience caused by the short notice” of dropping the lease since it wasn’t planned. The quote continued by saying an opportunity—which wasn’t specified—came up for the AM Racing team, and that Self needed to “reallocate all of [the] CTS resources” toward the NASCAR program.

Former track announcer Rodney Rodriguez expected that to happen eventually, but said he was optimistic when it didn’t happen earlier. He thought the speedway would stick around, and he thought Tim Self would too.

Holt said Tim Self was hopeful that those remaining would be able to work with the landowner to find a new leaseholder, but that wouldn’t happen. When asked by Jalopnik, Tim Self declined to comment further on his reasons behind getting out of the lease or about the track in general.

But it wasn’t long after Tim Self gave up the lease that things started falling apart at his former track. Fans and drivers immediately felt uncertain about the already-released 2017 schedule, with nine race dates. The official season-ending awards banquet, with tickets already on sale, was canceled soon after. Track regulars and participants later put together their own.

Track managers gave the job of relaying all official updates for the public on the track’s condition to Rodriguez and Holt. The track’s official website bluntly offered in large, white letters, “Unfortunately, Central Texas Speedway is no longer in business, sorry!”

Rodriguez still had hope for the track in January, telling the local Hays Free Press that the venue wasn’t planning to close anytime soon. He had every reason to believe that. Holt quoted the former leaseholder himself as saying he hoped racing could “continue at the track in 2017 and beyond.”

But as Rodriguez would soon learn, the track’s landowner, Rick Coleman, had no desire for it to open again. Coleman wasn’t looking for a leaseholder to take Tim Self’s spot, and he didn’t hesitate to tell Jalopnik that Thunderhill’s days as a race track were over.

The Liability Of It All

When asked about stopping by for a few final photos of Thunderhill, the owner simply said no. They’re “in the process of taking the racetrack out,” he told Jalopnik, and he doesn’t want anyone to get hurt. Once it’s out, Thunderhill won’t be a ghost track. It’ll be a fading memory without a trace on the map.

Not wanting anyone to get hurt has been a driving principle for Coleman during his time owning the land Thunderhill sat on.

During the winter, Rodriguez heard rumors from multiple people that an older man broke a leg while fleeing an on-track incident that moved toward spectators in the first turn last year. He had a sense that the landowner may not want to chance that happening again.

Coleman, however, denied knowing anything about a potential leg injury or any legal problems that might have been associated with it.

Jalopnik contacted Hays County Emergency Medical Services to verify the claims one way or the other, and Deputy Chief Jim Swisher said medics only transported “a couple of people” out of there and to a hospital over the years, most of them being drivers.

Swisher mentioned one incident where a tire came off and hit a crew member, but said “nothing out of the norm” usually happened out there. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act prevents any real specifics from being told about a medical incidents, but when asked about a potential leg injury in the first turn during the 2016 season, Swisher said it wouldn’t surprise him if that happened.

Overall, Swisher said Thunderhill was a “pretty well-behaved track.”

Still, Coleman was adamant about liability concerns—it’s the main reason he’s getting rid of the track, he said.

“I know nothing about car racing,” Coleman said. “I bought the land so I could control the noise for my own 600-some acres right there with it.”

Coleman said he held the land for about 12 years while it was a track, which doesn’t explain why he’d drop it so suddenly. He kept the track around for so long, he said, because he “thought it was good for the community.”

“I thought that the town of Kyle needed something for people to take their families to that didn’t cost them $500,” Coleman said. “It seemed like a whole lot of people were having a lot of fun, so I enjoyed that part of it.

“I just don’t want to be sued for someone getting hurt on that track. I didn’t build it, I don’t know if it was safe or if it wasn’t safe, but I’m out of there with no losses that I know of.”

(Jalopnik contacted multiple short tracks and a company specializing in insuring speedways to ask about the process of insuring a race track and how risky it could actually be. We received no responses over several weeks, but it’s no secret any race track needs insurance to run.)

Coleman knew Thunderhill had insurance, but it didn’t matter to him. He didn’t want to chance being sued. So, he said, he’s “just going to move on.”

Coleman said he doesn’t know what he’s going to do with the land yet, other than remove the race track. Coleman said he let Tim Self out of the lease early for “a little bit of compensation,” and doing so turned out to be what Rodriguez called “the perfect storm.”

A tornado came through soon after Tim Self got out of the lease, destroying the entrance sign and moving the building that housed the press box and suites. Coleman had to tear it down.

“It was lucky for me that he decided to get out of the lease a year early, or I’d be out there rebuilding all of that,” Coleman said. “So, it worked out fine for both of us.”

The Pipeline Running Dry

Things weren’t fine for the racers, or the track regulars. When Rodriguez got the gut feeling that things were over, he let everyone know.

“I reached out to a lot of the racing folks and said, ‘Look, I don’t know what your plan is, but you may want to consider dirt-track racing being our only option,’” Rodriguez said.

Many of these drivers have been left with the option of either racing states away or selling their asphalt cars in favor of unfamiliar—and more distant from NASCAR—dirt racers.

Smith, who still lives in the Austin area and has a lot of friends who raced at Thunderhill, said “there are a lot of people who are mad and bitter and sad” about dirt essentially being the only option. It’s where they put their money, and there isn’t much that can be done about the investment.

“There are a lot of people, they’ve got all of their eggs in one basket,” said Smith, referring to their asphalt cars that aren’t built to run dirt. “So, the closest place they can race is 12 hours away in Pensacola and Mobile, and it costs a lot of money to go race.”

“They scrounge up everything they can to be able to go race six or eight times a year at Central Texas.”

At the time Jalopnik spoke to Smith, things didn’t look great for the asphalt scene in Texas. They still don’t, to be honest, but enough racers came together to muster up two oval dates at Houston Motorsports Park, a racing facility that primarily hosts events at its drag strip but has an oval track on site.

The Houston track needed enough commitments of driver participation to run the proposed oval races, only recently adding them to its schedule. The first is planned for July 8, and the second Sept. 23.

It’s a small glimmer of hope for a dying discipline in the state, as running two events a year isn’t ideal for any sport.

But what’s surprising and worrying for those interested in small-town America is how thin of a thread this track hung on. Rodriguez said the track wasn’t “a huge revenue-generating machine in and of itself,” but it had participation and a leaseholder who seemed to have its best interests—as far as being successful was concerned—in mind.

There’s little to outwardly judge that of all tracks, this one should die.

But die it did, upon the abrupt departure of its leaseholder and by a landowner spooked by concerns over potential injuries when Jalopnik can’t find any record of that being a pressing concern. If Central Texas Speedway could go out like this, so could just about any of the circle tracks dotting the small towns across the country.

There was a little bit of hope for Central Texas Speedway in the confusion surrounding its abrupt closure, but it effectively ended once it came time for the 2017 race season. Even if Coleman wanted to keep the track going, Rodriguez didn’t have much hope for leaseholder candidates toward the end.

“It was the scenario where everybody knew somebody with money,” Rodriguez said. “But nobody really had money.”

Correction: Rick Coleman’s name was rewritten as “Rich” during edits. That has been corrected.