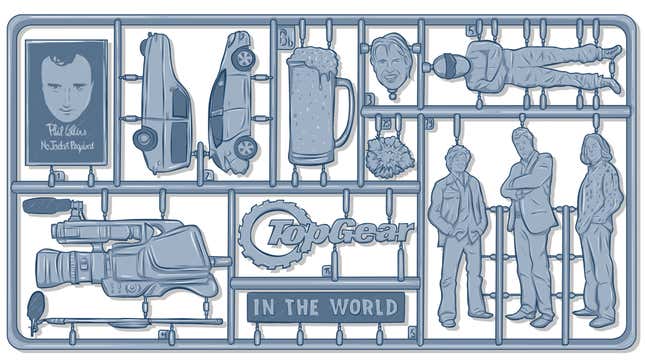

There we go then. The sun has set on what I imagine we will one day call Old New Top Gear. Now we sit patiently with seatbelts fastened and backrests in the upright position, awaiting developments from New New Top Gear / The Jeremy Clarkson Car Hour / James May’s Amphitheatre Of Cheese.

(Editor’s note: Sniffpetrol – by day, mild mannered former Top Gear script editor Richard Porter – explains how they used to put the show together and what it was like to be at the cutting edge of cocking about.)

This story originally ran in June 2015 and is being reposted ahead of the debut of the new Top Gear this weekend.

Whatever happens next, it’s going to be quite different from what I like to think scholars will one day call Top Gear Classic. It might be made in quite a different way too. I don’t know. I only know the way we used to make the show, which was with a mixture of sweat, panic, disagreement and potato snacks.

On the programme I hope historians will soon refer to as Top Gear – Original Taste the most important thing for any given item was, unsurprisingly, the idea. If we’re talking about a track test, that idea was always pretty simple; is it an interesting car and can we say moderately entertaining things about it while slithering around a runway for six to eight minutes?

Ideas for the big, three presenter films were rather more difficult. Coming up with suggestions wasn’t the hard part, it was the process that followed in which the idea would be prodded and dismantled and subjected to the same line of questioning it might receive from a four-year-old; Why? Why? No really, why? Why were we going there? Why were we taking those cars? Why were we doing this at all?

For those items in which we bought old rotboxes or built something of our own, it was important to have some headline question we were answering or some logical problem we were setting out to solve. Can you buy a car for £100 or less? Can you build your own amphibious car? Can we alleviate travel chaos brought on by snow using machines that normally sit idle in winter?

You needed the question for the studio introduction to give some line of logic, some small reason why we were craving your attention for the next half an hour or so. Once the item was up and running you could drift away from that original point, though I believe the best Top Gear stories never forgot it.

If the idea couldn’t pass muster in the office, in particular at the hands of chief scrutineer Clarkson who worried about this stuff more than anyone on the team, then it didn’t happen. Case in point, we once had this notion that we would re-invent the fire engine. Why were we doing that? Because it seemed like they were too big and too slow and therefore took too long to get to emergencies. The solution was obvious; Top Gear would build a small, high performance fire truck.

The trouble is, if you make a fire engine smaller there’s no room on board for all the ladders, hoses and burly men it needs to do its job. So it has to be big. And then it can’t get through gaps in traffic. So you make it smaller. And then it can’t do its job. And then…

We sat in a meetings for hours debating this round in circles before concluding with heavy heart that the ideal design was a fire engine, as in the sort we already have. The whole idea was thrown in the bin. It would have been easy to have plugged on simply for the sake of seeing Richard Hammond trying to fit a massive ladder onto the roof of a tiny van, but really we’d have been doing it purely for the jokes and, much though it may have seemed otherwise, such brazen comedy chasing was never enough for Top Gear.

An idea had to be better than that and, assuming that it was strong enough to withstand being debated and dismantled in the office, the production team would then crack on with finding cars, scouting locations and doing all the things necessary to make it happen. It’s all well and good saying that, for example, you’re going to re-invent the helicopter and to do so you’re going to need four camels and an exploding gazebo in a westerly facing garden but it isn’t going to happen without the hardest working, most dedicated and talented production team in television. Fortunately, that’s what we had. Even more fortunately, I was only joking about that helicopter thing.

While the ground work was being done, the next job was to script the item. It was sometimes complained that Top Gear became ‘too scripted’ which was the internet’s way of saying too set-up, too pre-planned, too close to a cack-handed comedy sketch. In truth, all TV shows are scripted. Obviously that’s true of drama shows like Game Of Thrones because dragons are heavily unionised and won’t come out of their trailer unless everything is agreed in advance. But ‘reality’ shows are scripted too, and so are documentaries and improv and the weather report. A television programme with no script at all would be a mess. A script doesn’t have to mean every single moment is written down in advance, it can be simply a series of points that lets everyone on the crew how we’re going to start, where we’re going to go, and what we hope might happen.

For a Top Gear track test, the script might have been pretty detailed. It would have presenter words on it, maybe a few chewy metaphors, and it would attempt to pace the item by deciding which lines were voice over, which were in vision, when the car would be moving, when it would be static and so on. Yet even this could change radically on the day, especially if a car revealed new facets or the presenter simply changed their mind on something.

A three header item out in the field would be much looser. Sometimes so loose a director would read the script and slowly sigh the words, Is that it? Ideally, there’d be a studio introduction that set out the logic of the story, some attempt to structure the start, maybe a few choice gags for each presenter to attack his colleagues’ choice of cars (though they preferred to keep the really good ones to themselves and unleash them like Indiana Jones’s whip when least expected) and then a broad attempt to order the item’s activities. Even so, one of the most common words on a Top Gear script was a vague, director-baiting place holder that simply said, ‘whatever’.

The actual process for writing scripts, or at least sitting down to fill in the gaps with ‘whatever’, took several forms. Sometimes Jeremy would get a rush of blood to the head and crack on with it on his own, then email me a first draft with a simple note at the top; ‘ADD FACTS AND GAGS’. Sometimes one or more of us would go over to his flat near the Top Gear office and work on it together. Clarkson would usually drive the computer, jabbing awkwardly at the keyboard with a single rigid digit on each hand, like he was trying to CPR a rat.

His ungainly typing style disguised his immense ability as the fastest writer I’ve ever worked with, rapidly producing first draft words that were sharper, tighter and funnier than most word jockeys could manage after 20 attempts. Every so often he’d pause as he searched for a chunky analogy to illustrate a point and we’d spend a minute or two bouncing gags back and forth, trying to make each other laugh. A lot of Top Gear writing was based around men in a room trying to make each other laugh.

Eventually, the script would be in some sort of workable shape, the gold plated unicorns would have been sourced, and we’d be in a position to film the damn thing. For this we would need three film crews – one for each star car in case they got split up and all the better to shoot the three way chats while allowing plenty of editing options to cut out the waffling bits – and a large van full of snack items.

Once the item was shot, it would disappear into the edit suite where over many weeks it would be diced and sliced and finessed into the finished item over which voiceover lines would be dubbed.

During our usual on-air routine, voice overs were done on a Monday evening the week of transmission, each presenter taking their turn to go into the recording booth while the other two loafed around in the control room, saying unhelpful things over the talkback loop, writing lurid slogans on other people’s scripts and generally behaving like children. Restless, middle-aged, deliberately annoying children.

Tuesday was writing day. In advance, I’d hash together a first draft studio script, pulling together the planned intros for each film, adding some thoughts for discussions out of them, and doing the ‘housekeeping’ of adding sections like the ‘Tonight….’ menu, the Stig ‘some say’ lines and the guest introduction. Then the presenters would arrive and we’d start the process of refining, revising or completely re-writing the words during which the three of them would read my jokes and either laugh, in which case I would inwardly fist pump, or say ‘hmm, not sure about that’, in which case I would inwardly sob, though outwardly I would stand behind them at the computer and do neither of those things.

At some point in the morning we’d turn our attention to the massive slick of press releases and pictures laid out on the floor behind us and the presenters would begin reading out things and firing one-liners at each other, the best bits of which I’d attempt to write down and later type up into bullet points from which the rough shape of the news segment would emerge.

Then, once the script was deemed satisfactory, and there were enough items in the news document, we’d sit down in front of the whole production team and read through our homework. If they laughed at the jokes, we’d go home happy. If the material fell flat on its arse we’d despondently go back to the computer and keep working.

Either way, we’d fetch up at the studio the next morning and Jeremy would thunder into the crappy presenters’ room at the back of our shabby Portakabin with a dozen new script tweaks, suggestions and jokes. The rest of us might turn up on a Wednesday morning with one vague thought for something that could be improved; only Jeremy would have lain awake all night worrying over tiny details and agonising over the smallest point until he’d got it right. Top Gear might sometimes have seemed like a big, freewheeling, slobbery, shambolic mess but you’d be amazed at the attention to detail. Someone once asked me what it was like to write on the show and the only way I could explain it was to say that we could easily lose 40 minutes arguing whether ‘raspberries’ was a funnier word than ‘hat’.

On those Wednesday mornings at Dunsfold we’d spend another couple of hours having debates about such things followed by a technical rehearsal in the studio, a spot of lunch and then all hands on deck. Are the presenters dressed? Is the audience in? Are the machines recording? Then it’s show time.

Or at least, it was. Maybe one day it will be again. Who knows how Top Gear and its pattern parts replica might turn out in the future. For all concerned, I just hope the production process is something like it was on the show we might one day come to call Top Gear – The Golden Years: Disorganised, exhausting, stupid and a simply enormous amount of fun.