You Can Play A Classic Racing Game Right Now On Whatever You're Using To Read This

Modern racing games owe so much to Sega's Virtua Racing. Released to arcades in 1992, Virtua Racing wasn't the first 3D polygonal racing game, though it was the first to really get it right, thanks to a blistering sense of speed and smooth, responsive 30 frame-per-second gameplay that outpaced its contemporaries at the time.

Virtua Racing also hit arcades almost a decade before you'd be able to experience anything like it at home. It'd take 12 years before Sega delivered a console port that could do the arcade original justice, and even then, the result wasn't terribly faithful. We didn't get a true arcade-perfect rendition of the seminal open-wheel racer until 2019, when the retro mavens at the M2 studio deconstructed and rebuilt Virtua Racing for the Nintendo Switch, as part of the Sega Ages series.

Surprisingly, last year saw yet another port of Virtua Racing many probably missed — this one from an unlikely source, that landed on an unlikely platform. It released in September, though I'd like to call attention to it because it's still sort of flying under the radar, even within enthusiast circles.

French developer Frederic Souchu has built a version of Virtua Racing for a virtual game console of sorts called the Pico-8. Now, the Pico-8 isn't an actual piece of hardware you can play games on, like a PlayStation or Xbox; rather, it's a set of specifications that simulates the restrictive development environments of retro systems. Pico-8 games are limited in size to a measly 32 kilobytes, for example, though this also means they can run effortlessly in any browser window via HTML5. And you can play this version of Virtua Racing right now, for free, at Souchu's website.

Compare the arcade original with the Pico-8 rendition of Virtua Racing, and it's immediately apparent the latter is far more pixelated and, for me anyway, a fair bit more strenuous on the eyes to play for long periods of time. Why even bother with this "de-make" of the game, then, when more faithful avenues exist?

First, it's just cool to see a developer cram a game like Virtua Racing onto hardware it has no business running on. To comply with the Pico-8's restrictions, Souchu had to convey the game's fast-moving 3D environments with a comically limited 16-color palette. He had to compress all the assets, which were ripped and reconfigured from Sega's 1994 Genesis port of the game, to fit within the Pico-8's infinitesimal storage limit. If I had to venture a guess, that's probably why the game's pit animations are missing, thought that's a forgivable omission given the circumstances. Making a polygonal racing game — even one as rudimentary as Virtua Racing — work within these technical confines is a massive achievement, and you can read a bit more about how Souchu did it via his development log.

The other reason why this version of Virtua Racing matters requires a bit more historical context. Sega has released five ports of Virtua Racing for various platforms since the game debuted in arcades almost 30 years ago, but the first two in particular — the ones that appeared on the Genesis and 32X — had to do a lot with very, very little, not terribly unlike this Pico-8 rendition.

Virtua Racing was originally coded for Sega's Model 1 arcade board, hardware built for the purposes of 3D polygonal gaming, unlike the sprite-based, 2D games that had come before. Model 1's texture-less polygons look crude by today's standards, but the arcade machines it was used in reportedly cost $15,000 for operators to buy at the time. The industry was moving fast, attracting investments from companies well outside the gaming sphere, like GE Aerospace, which later partnered with Sega to improve on its original Model 1 design. The resulting Model 2 architecture powered landmark titles like Daytona USA, Virtua Fighter 2 and Sega Rally Championship.

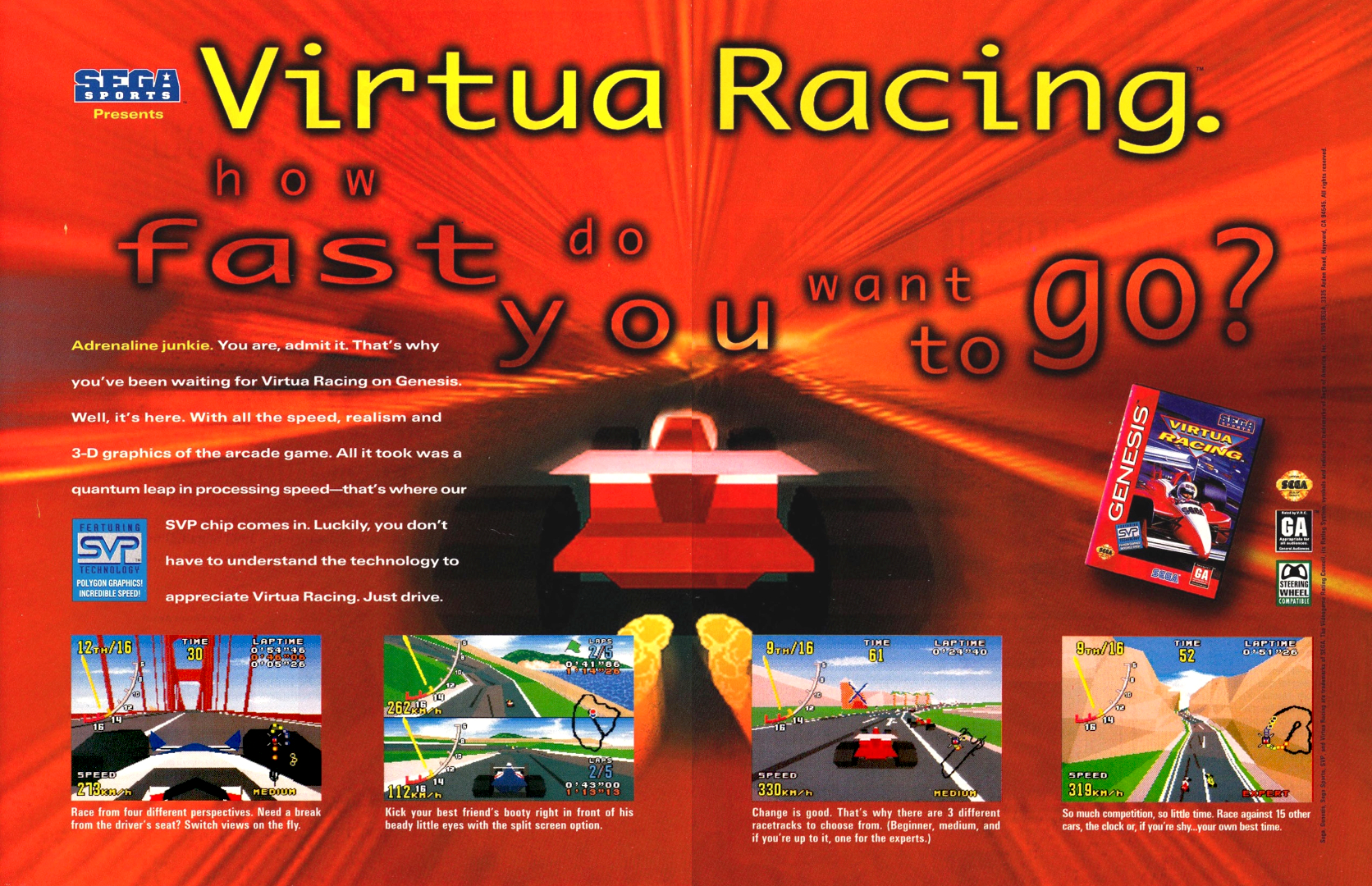

Virtua Racing was built on some pretty remarkable tech for its day, then. Needless to say, bringing the game to a consumer machine like the humble Genesis required a massive effort, which is why the game's Genesis cartridge included a bespoke chip that added rudimentary polygon-crunching power to the console — and $50 to the price tag. It cost $100 ($175 in today's money), double what Genesis games typically went for.

Seeing Virtua Racing run on a Genesis isn't pretty, though it is impressive. There's an art to porting a game to a platform that shouldn't be powerful enough to run it. When done without the proper care or time, the result can be disastrous, as Cyberpunk 2077 has reminded everyone. When done well, it's a testament to the developers' programming prowess and commitment to optimization.

Bearing this in mind, the Pico-8 version of Virtua Racing is magnificent. All three of the game's circuits have been preserved here. The game's charming-but-basic soundtrack — mostly consisting of snippets of music that play when passing checkpoints — have been re-composed by artists RubyRed and Mavica to accommodate the Pico-8, and they sound great. It even drives well enough, and it'll work with a gamepad if you have one connected to your computer.

I'm in awe of the result. This is a take on a hugely influential arcade classic that can stand tall alongside Sega's own efforts to bring Virtua Racing home in the '90s. Plus, it can run on a potato. Whatever you're reading this on, I almost guarantee you it can run this game — including your smartphone. So stop reading and get to racing already!