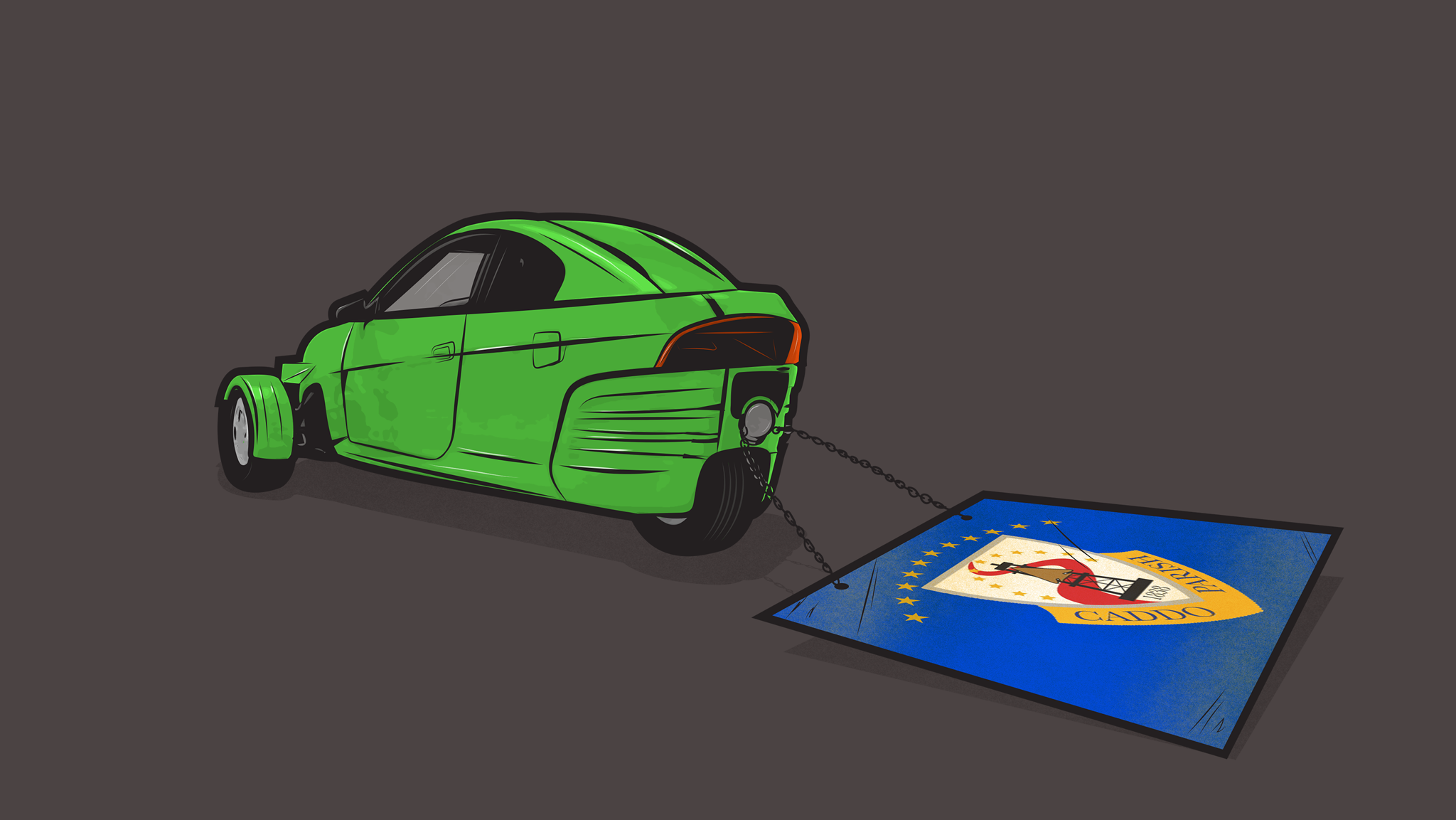

Why This Job-Starved Town Thinks Car Startup Elio Motors Took It For A Ride

SHREVEPORT, La.—When Mark Jones took over the Chevron gas station he owns here more than three decades ago, it was in a sleepy and undeveloped part of town. Quickly, though, things changed. A nearby General Motors truck assembly plant opened in 1982 and gave way to a crush of development. Neighborhoods sprouted to house the factory's 3,000 employees, and a stable of businesses popped up to support the community.

"Starting in 1990, the place really took off," Jones said. "General Motors was going gangbusters, and the economy was very, very good—up until about five years ago."

That was the year GM closed the Shreveport facility, striking a heavy blow to the area's economy. Like many there, Jones has struggled ever since, forced to lay off employees and cut back on store hours.

"I've looked at everything on the expense side of the ledger and made cuts wherever I could," he said.

Officials in Caddo Parish, as Louisiana counties are known, hoped to alleviate the area's economic stress with a rescue plan for the factory hatched shortly after GM's departure.

The idea: turn the plant over to a well-established billionaire real estate developer, Stuart Lichter, who, in turn, would bring a new startup car company to the facility that aimed to hire 1,500 employees. Perhaps, they wagered, someone would launch the next big thing that could resuscitate the area.

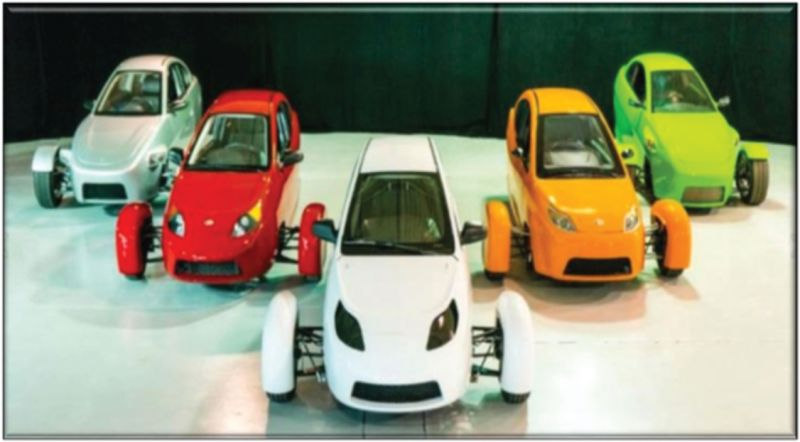

That prospective carmaker ended up being Elio Motors. The startup had pitched an ambitious plan to build super inexpensive three-wheeled vehicles that could achieve up to 84 miles per gallon—an eye-popping figure, even more so in the era of $4-a-gallon gas.

It was a long shot. In recent decades only Tesla has managed to get a new car company off the ground and survive. But with an A-list of suppliers as backup, more than 65,000 reservations placed on the vehicle, and a low $7,450 entry price for the car itself, Elio Motors' bid seemed primed for success.

Production, Elio Motors said, would begin in 2014. In return, the parish kicked in $7.5 million and ceded control of the plant's future to Lichter, banking on the premise that he'd bring jobs back to the region.

With a high unemployment rate at the time, Shreveport could use the help—and Elio Motors knew it, a sentiment expressed by the company in 2014 when it applied for a $185 million loan from the U.S. government's Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing program. That program previously assisted "green car" efforts from the likes of Tesla and Fisker. Elio Motors portrays the loan as crucial to its chance of becoming viable.

But like innumerable startups before it, Elio Motors has been hopelessly beset by financial problems, leading to frequent delays and an uncertain future of both the car and company.

What's more, the fate of the ATVM loan—and, by extension, the company itself—now rests with the Trump administration, which has a proposed budget that calls for eliminating the program. Elio Motors says it still needs to raise $376 million to start making cars, and with automakers increasingly pressing ahead to develop tomorrow's electric and autonomous vehicles, the company's flagship three-wheeled car may wind up a black sheep in the auto industry of today.

Elio Motors is now looking to raise $100 million from investors in a fresh round of funding, but that comes with yet another caveat: production isn't expected to begin until late 2019.

That's hardly the only problem. Lawmakers are calling for an investigation into the Shreveport deal. Louisiana officials fined the company over $500,000 for allegedly violating state law—the state claims Elio requires a license to operate as a "manufacturer" in order to accept non-refundable deposits, though Elio Motors disagrees and said it plans to appeal. And, as of this summer, Elio Motors reported having only about $4,000 in cash remaining.

Furthermore, a close analysis by Jalopnik of the real estate deal over the plant uncovers questions about who actually comes out ahead if Elio Motors doesn't make it.

And so, five years after the Elio Motors deal was first announced, Jones and others in the southwest Shreveport area are still waiting for their corner of the world to come alive once more. Expectedly—and, really, understandably—the delays have created friction in the parish.

Today, the only noticeable presence of Elio is a plain sign that sits along General Motors Boulevard—a stark reminder of the factory that once buzzed with life to produce Chevrolet Colorados and Hummers. The sign directs truck drivers with deliveries for the startup on where to go.

"I sure would like somebody to explain to me why... we don't have any measurable employment over there, five years later after the plant's been closed," Jones said. "And they keep fooling around with this Elio Motors thing, and it should be quite apparent to everybody involved this is not a feasible idea."

‘One-In-A-Million Chance’

Initially, investor Lichter and Elio Motors welcomed being interviewed by Jalopnik. But when the automaker, Paul Elio himself and Lichter—who has reportedly invested $20 million in debt and equity in the company and has a 30 percent stake in Elio Motors—were approached with additional questions for this story, a spokesperson declined. The official said attorneys advised that it's "not in a position to respond" due to the "quiet period" around the company's recent registration statement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission as part of the proposed $100 million public offering.

On its website, Elio Motors proudly touts having more than 65,000 reservations for the company's car; deposits can be placed for as little as $100 and up to $1,000. As of June 30, the company said it has received about $28 million in customer deposits.

Of that, $1.21 million are refundable deposits, with the remainder in nonrefundable deposits. Interestingly, Elio Motors reported in mid-August having received roughly $700,000 more in nonrefundable deposits since the beginning of the year.

The startup makes it clear in SEC filings that it has "no obligation" to return money to customers with a nonrefundable deposit, which, to date, Elio still accepts.

Last month, Nathan Swartzbaugh learned how firm the "no obligation" provision is. Swartzbaugh, 28, paid $1,000 for a nonrefundable deposit in 2014, excited about landing a car with the fuel-efficiency Elio Motors said it could attain. But after three years, he grew tired of waiting for the startup to begin production, so he filed suit in a Texas small claims court against the company, alleging it committed fraud and breached its contract with him.

"Now, they're not going to go bankrupt because every day they're open, they're collecting more reservations for something they'll never produce," Swartzbaugh told Jalopnik.

A judge dismissed his claims in June, but he vowed to appeal.

"On their website, they're acting like this is a sure thing," Swartzbaugh said, "when they really need to put a disclaimer that you have a one-in-a-million chance in getting this."

A Messy Building Process

If you didn't look at Elio Motors' financial statements, you'd be forgiven if you failed to realize the precarious situation they've been in. The company has excelled at public relations, always out front at auto shows drumming up interest while showing an insatiable thirst for generating attention on social media.

(In a pitch to Caddo Parish officials, Paul Elio leaned on the number of followers on the Elio Motors' Facebook page as a way to illustrate interest in the startup, saying social media interest in it compared to everything from Walt Disney and Mercedes-Benz to Leonardo DiCaprio.)

But social media posts do not build cars, and the parish has seen one delay after another, with investor Lichter at the center, trying to balance the provisions of the deal—attracting tenants to the space—while also aiming to support his investment in Elio Motors.

There was a glimmer of hope for residents of Caddo Parish and the Louisiana plant, when, in early 2016, Elio Motors became the first equity-crowdfunded company to be publicly traded and list its shares in the stock market, thanks to new SEC rules. It received a $1 billion market valuation, earning it the coveted status as a unicorn startup. (The company received only $16 million of its $25 million goal, from 6,600 investors, according to records and reports.)

With the influx of funding, Elio Motors set about working on building prototypes for safety, system performance, manufacturability and durability tests. The company even planned to build the prototypes inside a new Pilot Operations Center in Livonia, Michigan.

The knowledge gained at the center would then be "transitioned to our production facility in Shreveport for our 100 pre-production vehicle builds that are slated for the end of the year," Gino Raffin, the startup's vice president of Manufacturing and Product Launch, said in a statement at the time.

But if stakeholders in Louisiana wanted to know why Elio announced more delays in 2016, they should've been looking 1,100 miles to the north in Michigan: the build effort in Livonia was an unmitigated disaster, according to a former employee who spoke to Jalopnik on the condition of anonymity.

The employee said more than a half-dozen people were hired for an expected four-month contract to build five Elio Motors prototypes.

"That was the start of what we should've realized is going to be a long nightmare build," the employee said. For the first two months, there were no supplies to build the prototypes, they said.

"Paul was there to see the car being built, but he was never there to address the problems with it," the employee said. "Our thoughts were, 'This is your design, this is your name, shouldn't you have input on why it's not going well, why it needs to be changed?' He was never there for it."

"It started immediately with parts trickling in, guys standing around painting the shop," the employee said.

The design of the car seemed right on a computer model, the worker said, but "nothing fit." Door panels didn't fit. Frames had to be handmade.

"There was no communication with the suppliers, what needed to be done, what they should do," the employee said. "We had to cut 300 holes in these frames to make the interior fit, and to bond on the plastic panels."

All in all, the contract lasted three months longer than expected. Only two cars were completed. A third prototype was mostly finished, the employee said, but an engine wasn't completed for it.

By November, Elio Motors' funding had dried up. "They brought us in... and said, 'We don't have any money, thank you for working for us," the employee said.

The financial acumen described by the employee doesn't jibe with the idea of a startup looking to run a lean operation and, eventually, develop it into a financially sustainable company. And the employee said executives were no where to be found, despite the glaring situation.

"Paul [Elio] was there to see the car being built, but he was never there to address the problems with it," the employee said. "Our thoughts were, 'This is your design, this is your name, shouldn't you have input on why it's not going well, why it needs to be changed?' He was never there for it."

A Real Estate Deal That May Not Add Up

In recent years, criticism of the company has ratcheted up. At a time when Elio Motors is looking to raise $100 million, the startup's potential new investors will almost certainly turn their attention to Caddo Parish.

But unpacking that situation is complicated. The GM plant was salvaged by an intricate real estate deal involving Elio Motors, the parish, and investor Lichter.

It hasn't been an easy marriage, with Lichter helping keep the startup alive in what seems like a quixotic endeavor. One state lawmaker alleged it was a "crime" for Lichter, as a major shareholder of Elio Motors, to sub-lease part of the factory to the startup.

But after sifting through hundreds of documents related to the transaction, it comes across less as potentially illegal than it is just outright frustrating.

"I thought it was a great real estate deal, whether I got a car company or not."

There was an initial consideration by the parish to invest directly in Elio Motors, but that was later overruled as unworkable under the law. Instead, a convoluted four-party transaction was arranged between Elio Motors, Lichter, the parish, and RACER Trust, the entity formed after General Motors' bankruptcy to sell or dispose of the automaker's shed real estate properties in 14 different states. (Remember, the plant is a former GM facility.)

The deal's structure seems sensible and fine to officials who support the arrangement; the complexity of the matter strikes critics as a disaster. It worked like this:

-

RACER agreed to loan Elio Motors $23 million, contingent on receiving monthly payments of $173,500 in return and that it would use and develop the property to create at least 1,500 new jobs. RACER retained a security interest in the movables, meaning the trust had a legal claim on the property as collateral if Elio Motors stopped making payments.

-

The Caddo Parish Industrial Development Board (IDB), an economic agency of the parish, paid $7.5 million to a Lichter entity to help finance the purchase of the factory.

-

With the money from the parish, Lichter then acquired the factory from RACER Trust with additional financing.

-

Lichter arranged a deal that concluded with Elio Motors acquiring ownership of the machines and equipment inside the building.

-

Lichter then transferred the property and surrounding land back to the IDB.

-

The IDB leased the property and land back to Lichter. As part of the lease, Lichter wouldn't pay property taxes for up to 20 years, and in return he agreed to make a rental payment to the parish of $25,000 per month, eventually going up to $60,500.

-

Lichter sub-leased a significant portion of the factory to Elio Motors.

It's complicated, but the arrangement was said to be necessary to preserve the incentives structured into the deal for Lichter and the parish.

A controversial measure allows Lichter to obtain title to the facility as early as next year, once his lease payments equal the $7.5 million invested by the parish. If he wanted, Lichter could purchase the factory beforehand at the same price, plus interest.

It's a low hurdle for a 3.7 million square foot facility that GM had poured over $1 billion into renovations by 2004. (An appraisal conducted by the parish found the equipment inside the factory to be valued at $8.04 million and the facility itself to be worth $4.5 million. But Elio itself has taken pains to note GM's previous investment of $1.5 billion, calling it "one of the most modern automobile manufacturing facilities in North America.")

While Lichter seems genuinely intent on helping bring Elio to fruition, he also saw it as a potentially lucrative opportunity.

"I thought it was a great real estate deal, whether I got a car company or not," Lichter said in an interview with Jalopnik in August.

With two polarized sides staked out, the situation has deteriorated into a he said-she said affair. Caddo Parish officials who support the deal say it generates rental revenue for the community from Lichter, while he and Elio Motors try to raise funds to launch production.

Lichter's also required to market the facility to other potential tenants, they say, pointing to a Hyundai subsidiary that opened in a small swath of the factory in January, bringing a few hundred jobs along with it.

Critics, meanwhile, say it's a giveaway to a rich guy who'll soon have the option to purchase the factory at a considerably low price and in return seek a significant profit.

"RACER [Trust] promised us jobs and they're obligated by their contract to put communities in position where they can do most with their plants," said Matthew Linn, a parish commissioner.

Linn pins blame on RACER for bringing Elio Motors and Lichter to the table in Caddo Parish. RACER's mission statement, he points out, is to work to "attract prospective buyers" for the old GM plants to "create new jobs and new economic growth on these properties."

After several years, in which the Caddo Parish plant has sat more or less vacant, it's obvious RACER hasn't fulfilled that promise, Linn said.

"And they put us in the position where we could do the least with our plant."

The Founder’s Dream

Before Paul Elio ended up in Louisiana, he endured a number of courtships with automotive towns in the Midwest that went nowhere.

An Arizona native, the 53-year-old launched his bid to create a car company from scratch in 2008. For years, he operated a firm called ESG Engineering, but in the wake of the American auto industry's implosion a decade ago, ESG's revenue shrunk quickly. That left him in desperate need of cash just to pay his bills.

"All my assets were gone. I had hundreds of résumés out for everything from high-end jobs down to Starbucks," he told the Wall Street Journal in 2015.

While he set about designing a two-seat commuter car, called the Trikke at the time, Elio shopped his proposal around to old manufacturing towns in the Midwest. In early 2009, records show, he sought an investment from a Detroit pension system, whose board signed off on the idea, provided he relocated into the city.

A letter Paul Elio sent to the pension board, obtained by Jalopnik under a Freedom of Information Act request, stated he felt "very confident" the company would obtain the "majority" of its funding from an Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing program loan administered by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Five years after the Elio deal was first announced, Shreveport is still waiting for its corner of the world to come alive once more.

At the same time, he looked north to the City of Pontiac, where in 2010 a GM plant had been closed and turned over to RACER.

Elio told a Pontiac pension board the low cost of the Trikke—at the time priced at $5,500—coupled with the vehicle's impressive fuel economy would make it a success. "There are 25.6 million driving age students that could impact this market," he said at the time, according to a summary of his presentation.

The idea went nowhere, at least in Pontiac. While Paul Elio struggled to find a suitor, his money problems continued to ratchet up. In 2010, Elio, Elio Motors, and his firm ESG Engineering, were hit with a roughly $830,000 judgment as part of a case filed by the Arizona Bank & Trust. The bank said Elio and his companies had failed to make payments on a number of business loans, according to the 2010 complaint. (The judgment was paid off in 2013, records show.)

It was around that time an opportunity opened up in the south.

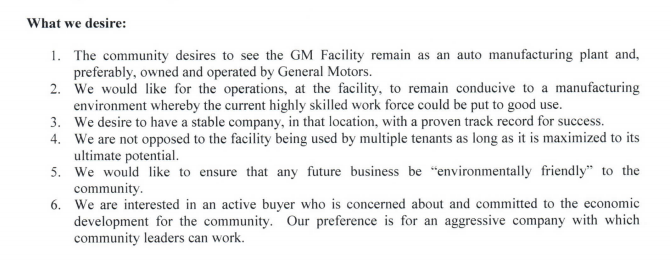

In May 2011, RACER acquired the GM facility in Caddo Parish. As other RACER properties had met the fate of a wrecking ball, parish officials stressed that they wanted to preserve the asset, with the hope of landing another manufacturer to fill GM's shoes.

In a September 2011 letter, Caddo Parish administrator Woody Wilson told RACER that the community desired to "see the GM Facility remain as an auto manufacturing plant, and preferably, owned and operated by General Motors." This was for the sake of jobs and the area workforce's skills, he wrote in the letter to RACER's redevelopment manager.

The parish needed the jobs. Its unemployment rate has long outpaced the state of Louisiana; in 2015, the median income in Caddo Parish was $41,000, about $10,000 dollars less than the U.S. average.

Wilson included an additional bulletpoint to articulate what the parish didn't want.

"We do not want to see the property purchased by an out-of-town realty firm that would allow the facility to sit idle for a prolonged period of time without it aggressively seeking to place the property back into the economic mainstream," he wrote.

That's when Lichter, the kind of out-of-town real estate guy from California that Wilson wanted nothing to do with, entered the picture.

‘Nothing Has Changed’

Similar to the parish, RACER Trust also "insisted" that the GM redevelopment have a manufacturing component, Wilson told Jalopnik.

RACER knew Lichter from previous sales, and the entity first introduced him to Paul Elio. After Lichter and Elio hit it off, RACER brought both of them to the table in Caddo Parish.

"We didn't know who they were," Wilson said in an interview at his office.

Wilson described the complex deal as a calculated measure to preserve the asset, generate some revenue for the parish from Lichter, and potentially land jobs. If Lichter and Elio Motors succeeded, a new automaker would rise; if Lichter wanted, he could purchase the title to the factory and sell it at his will.

If Lichter chose the latter, Wilson said, the property would go back on the parish's tax rolls. Wins all around.

The deal took months to negotiate. By fall, attorneys for the parish, RACER and Lichter had a framework in place, where the parish would finance $7.5 million of the acquisition costs for the factory, while Lichter would pay the parish back in monthly rent payments. Lichter would then lease the facility with the intention of sub-leasing a portion of it to Elio. Commissioners approved the deal in August 2013.

But commissioners who spoke with Jalopnik said they continuously struggled to get basic questions answered by the attorneys negotiating the deal.

Linn, the commissioner who was president of the board at the time, said he was "hopeful" when Elio announced the intention to move to Shreveport in early 2013. But throughout the year, he was "in the dark" about how that would happen. As details trickled out, Linn became highly critical of the deal, despite ultimately—and, he now said, regrettably—voting for it, after being convinced by parish officials that it would be a solid deal for the community.

"The right questions were not asked and the right questions were blocked," he said. "Anybody that asked right questions got shut down."

In August 2013, after the commission approved the deal, another commissioner, Stephanie Lynch, filed a lawsuit to block the measure from being enacted, alleging it violated state law.

The case argued that the parish had no financial guarantees in case Elio or Lichter failed to keep up their end of the bargain. But Lynch lost her motion for a preliminary injunction, which allowed the deal to move forward.

In an email, Lynch declined an interview request.

"Nothing has changed," she said. "It is exactly as I called it four years ago."

By Christmas Eve 2013, the deal made its way to the Caddo Parish Industrial Development Board. That day, the IDB voted to finance the plant for $7.5 million.

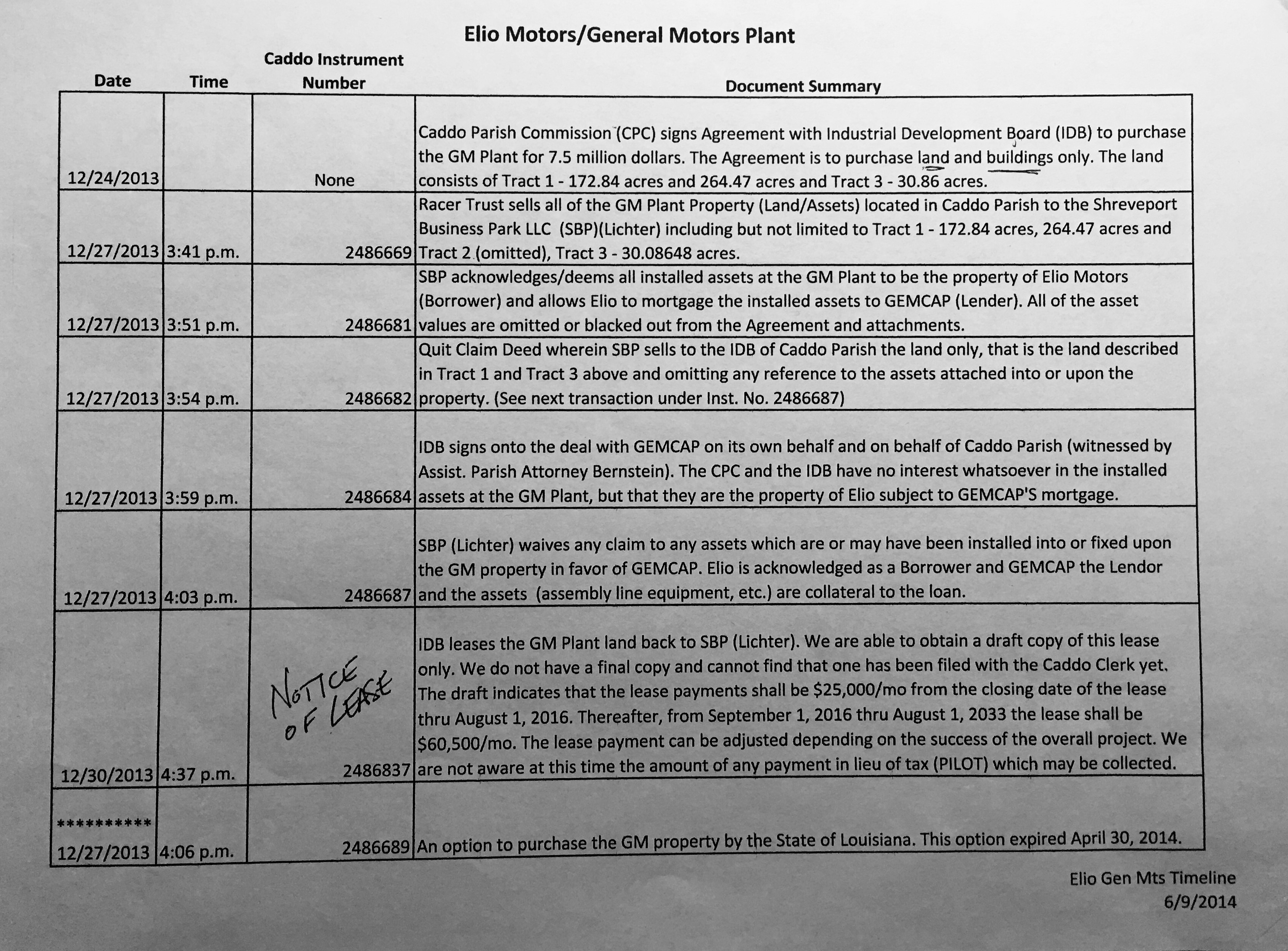

Three days later, December 27, attorneys for all parties involved met to enact the remaining measures. A lighting-fast set of real estate transactions played out over the course of just 22 minutes.

The complexity of the deal—and how fast it was nailed down that day—confounded Caddo Parish Sheriff Steve Prator, who criticized it as "bad government" and has since examined the arrangement.

"I mean that's a pretty sweet deal, when you can talk the government into buying something," Prator said in an interview, "and then you lease it from them, get all sorts of [job] credits and advantages, and then as soon as [that $7.5 million is paid back] all the sudden you get it?"

Then there's Paul Elio's financial situation. He isn't a billionaire like Elon Musk, but Elio Motors seems to have been good to him. He lives in Phoenix, and today he earns a $250,000 annual salary as CEO of the startup, according to SEC filings.

But after the startup was launched in 2008, records show, Paul Elio, the startup, and his engineering firm ESG racked up nearly a million dollars in debt—including the $830,000 judgment from a case involving failure to make loan repayments to an Arizona bank. In 2012, a roughly $11,500 judgment was entered against Paul Elio personally for debt owed to Discovery Bank. And in late 2015, he was hit with nearly $100,000 in federal tax liens filed against him by the Internal Revenue Service.

Over time, though, those debts disappeared. In 2013, after billionaire Lichter came on board, the Arizona bank judgment was cleared, and the credit card debt was paid off. In 2016, the federal tax liens were released.

"Some guardian angel came around and paid those off for him," Linn joked.

Whose Problem Is It?

Caddo Parish officials who support the deal benefit from the complexity. When you unpack the details, they assert, you'll find the parish is financially protected, even if Elio fails.

"Elio is not our relationship," said John Atkins, a commissioner who was elected in 2016. "Elio has his relationship with Stuart Lichter... he's entitled to sublease to whomever he wants as long as he stays in compliance with our lease."

And officials say Lichter is in compliance. As part of the deal, he pays no property taxes over 20 years, but in return the parish receives $60,500 per month in rental payments for everything from a separate Lichter entity, Industrial Realty Group (IRG), which translates to $726,000 annually.

The parish previously received $1.2 million in property taxes from GM when the automaker owned the facility, officials said. The carrying costs of the site—estimated at about $1 million annually—are handled by Lichter.

That's why Wilson and Atkins say the deal's a net-positive for Caddo Parish.

"We knew [Elio was] a startup, we're not naive," Wilson said. "Most startups never succeed."

Nevertheless, the arrangement provides Lichter the opportunity to outright own the facility. The optics of a billionaire developer even having the chance to turn a profit on the plant is unseemly to critics.

"If Mr. Lichter is able to put together a deal that allows him to make a profit as long as we get the jobs, and maintain the facility, and protect taxpayer dollar, then I think that's a fair trade."

But the deal requires Lichter to market the factory to prospective tenants, Wilson and Atkins stress. If Elio doesn't work out, that's fine, so long as Lichter's rent payments to the parish remain on time.

"We can't gamble the taxpayer money," Wilson said. "We just have to preserve it with a reasonable return. If Mr. Lichter is able to put together a deal that allows him to make a profit as long as we get the jobs, and maintain the facility, and protect taxpayer dollar, then I think that's a fair trade."

Despite the proclamations from Atkins and Wilson, it's hard to extricate the startup from the parish, especially when Paul Elio's constantly out in the press, trying to drum up excitement about launching production one day in Louisiana. And at the time negotiations were ongoing, the implication seemed to be that Elio Motors and Lichter came as a package or the deal would come unglued.

In a June 2013 email, Caddo Parish attorney, Charles Grubb, said a focus of the deal is whether the "parish's investment will assure the commencement of operations at the Caddo Parish facility."

"The answer to that question is 'no'," he wrote. "With Caddo's infusion of funds, there will still be contingencies that will have to be met by Elio Motors in order to begin manufacturing."

Still, if you ask Atkins, the startup's essentially irrelevant to the parish. Over the course of a 75-minute interview inside Wilson's office, Atkins seemed irritated whenever Elio Motors came up.

"[Lichter] is paying us a fair market rate and covering our overhead while we look for an opportunity," he said.

‘Nobody Is More Upset About It Than Me’

If you take Wilson and Atkins' view—and accept that the parish is safe even if Lichter decides to throw in the towel with Elio and tries to sell the place—then the deal's criticism could seem hollow. Lichter can spend his money to keep Elio Motors alive, he pays the parish monthly rent that nearly recoups what the community lost in property tax revenue when GM vacated, and the region retains a huge asset that could attract significant tenants down the line. (Toyota and Mazda, for instance, are looking for sites to build a new $1.6 billion factory, and they're reportedly fixated on locating in a southern U.S. state.)

But, beyond the small Hyundai subsidiary that opened in January, the sprawling GM factory has more or less sat dormant for nearly five years.

With a well-connected transit network including rail already nearby, and an able workforce in the region, it's no surprise a significant chunk of the community has taken an adversarial view to the situation.

Elio Motors hasn't built a single production car in nearly 10 years; what if someone could make better use of the facility and actually deliver on the promise of jobs, a promise that has still not materialized?

And indeed, more and more the Elio car feels like an idea deeply rooted in the last recession—it's cheap, it's small and it's great on gas. It feels out of step with the way people buy cars now, by financing SUVs at absurdly lengthy loan terms, to say nothing of a car industry moving more toward electrification and autonomous driving.

Paul Elio said he "absolutely" understands the frustration.

"Nobody is more upset about it than me," he said in an interview in May. "But nearly all of the delays have been funding-related."

The delays continued to mount, and more questions started being asked, fostering an environment in town where stakeholders honestly began to consider if Elio Motors was ever intended to become a legitimate venture.

"Elio was brought to the table to hurry the lease along for the real estate transaction," said Steven Jackson, the current president of the Caddo Parish board of commissioners. "So Elio was the bait. Elio was the big conversation that the news and everybody jumped on and got hyped about because it was 1,500 jobs."

He continued: "But that's not really what was happening. What was really happening was this plant was being stripped down and there was a lease-purchase agreement being put together that benefited Stuart Lichter. Yeah, we're going to get our $7.5 million back, but he's going to get a billion dollar plant in return."

Lichter himself told Jalopnik that he's in a "conflict of interest position," trying to help keep Elio alive while still honoring his commitment to the deal with the parish. Of course he wants Elio to succeed and launch production at the GM plant.

"I knew enough to know that if a car got on the road at that kind of price point it would be really, really significant... for lower income people in this country who live day to day," Lichter said.

Linn and other critics suggest that Lichter and officials missed the boat on luring another potential tenant to the site, Jaguar Land Rover, which sparked a storm of criticism that hasn't let up. The frustration makes sense; rather than betting on a startup, the parish could've scored an established automaker with a demonstrated record of success in Jaguar Land Rover, had it panned out.

But Lichter said it was never even a possibility.

"It was never real," he said. "They approached me. We started having discussions with them. They then said they didn't want to deal with me, they wanted to deal with the state. The state had a guy there who basically asked me to step outside, right? We said, 'Certainly, you go make the deal then you come back to me.' And I never heard from them again. Made repeated phone calls to them to reinsert myself, and got blamed that I killed the deal."

Jaguar Land Rover also wanted the entire factory. At one point, Lichter said, he put another facility in Shreveport under contract, just on the possibility that Louisiana could orchestrate a deal for the GM plant. (The state had a six-month option to assert itself into the mix and make a deal happen.)

Paul Elio was willing to play ball, Lichter said, but the state's deal never came to fruition.

"I spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to have another facility in Shreveport under contract just on the potential the state would make the deal ... and I get ripped and blamed that the deal didn't happen." (A Jaguar Land Rover spokesperson declined to comment.)

Lichter's clearly bitter about the criticism he has received from some commissioners and residents in town. He said he empathizes with the frustration over the company's repeated delays and makes no bones about the fact that Elio Motors' potential for success is nothing short of a Hail Mary play.

Over an interview in a diner in the Hudson Valley, Lichter came across as genuinely devoted to the idea of producing an affordable three-wheeled ride.

"I don't think any of the other companies we've helped start were a concept this huge or a concept that [could] help fight poverty this country," Lichter said. "Mobility is one of the biggest causes of poverty in this country," he added.

Not Much In The Bank

But that hasn't stopped the bleeding. By May, Elio Motors reported a need for $376 million in additional financing to launch production.

By summertime, Elio Motors was staring down a huge financial penalty from RACER Trust, after falling behind on the monthly $173,500 payments to the trust. SEC filings show the startup hopes to pay RACER its overdue bill—now totaling roughly $1.75 million—along with an interest payment at 18 percent.

Elio Motors also had a stipulation to create 1,500 jobs by July 1, or pay a penalty of $5,000 for each full-time permanent direct job that fell below that amount. That deadline came and went.

RACER nonetheless granted Elio Motors an extension on the jobs deadline, saying the flexibility in the deal allows for "another prospect" to potentially utilize the space at the GM plant.

"Having evaluated the relevant factors... RACER Trust has made what it considers to be the responsible decision to extend the job-creation deadline," RACER said in a statement at the time.

In July, the company was fined $545,000 by the state of Louisiana, which claimed the company was operating as a "manufacturer" and therefore should have a license to accept non-refundable deposits for its proposed three-wheeled ride. Elio has vowed to appeal.

Hoping to find a new infusion of funds to generate additional interest in the car, Elio Motors retained Wall Street firm Drexel Hamilton to help raise up to $100 million and list the company on the NASDAQ Global Market. It's unclear if Paul Elio, Lichter and the company's remaining board directors would retain their own shares, or potentially cash out while the stock price remained around $5-6 a share.

A semi-annual report filed with the SEC in August didn't paint a brighter picture.

At the end of June, Elio Motors said it had roughly $4,000 in cash, and a working capital deficit of $38.31 million—compared to $120,000 in cash and a $42.14 million deficit in December. The deficit was cut "primarily" because of RACER's decision to delay the jobs creation penalty, the filing said.

Paul Elio took issue with the focus on the deficit figure and pointed to some of what he described as "positive" news in the filings, like the startup's supplier relationships.

"We have already established letters of intent with industry-leading suppliers to provide the Elio's systems and components, such as Linamar Corporation for the engine, Aisin for the transmission, and Hyundai Dymos for the seats," the filing said.

But Elio Motors is still banking on the government's Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing program. The ATVM program hasn't doled out loans in years (and received significant criticism during the Obama administration) but the company has been in-waiting for a confirmation since January 2015, when the U.S. Department of Energy said that Elio Motors met the technical criteria for the loan. Without it, the production timeline could be delayed again.

"If we fail to obtain these loan proceeds within the timeframe needed to support our proposed production timetable or not be funded at all, it is likely we will experience significant delays in our production timetable," the filing said. (A DOE spokesperson said it considers the application process to be "business sensitive information" and therefore couldn't offer comment.)

Elio Motors' reliance on the ATVM program also pins itself to the whims of President Trump, whose budget proposed in May plans to eliminate the program and allocate funds elsewhere.

"We cannot predict which of the President's budget proposals will become effective," the company wrote.

Outside of Shreveport, the Elio Motors community is a fractured one nowadays, with a strong contingent of former fans now openly railing against the startup for taking years to get off the ground.

Reservation holders may be out a few hundred bucks—customers can reserve a car for as little as $100 and up to $1,000—but Caddo Parish is still waiting for Elio Motors to become something more than an idea they hear on the news. Or at least for Lichter to bring in more substantial tenants.

"After five years if the guy hadn't raised the money by now, let's move onto something else," said Jones, the owner of the Chevron station near the factory.

"But for whatever reason—I don't know if I have to go back and accuse people of ignorance, or corruption, or both, but that's all I'm left with when I think what's involved with it."

A Burned Town

Bob Brown, a Shreveport resident and former worker at the GM factory who handled communications for the local union chapter, doesn't believe the funding's ever going to come—be it from the ATVM program or investors on Wall Street.

A former spokesperson for the local UAW chapter, Brown, who retired in 2008, said that Paul Elio and Lichter previously approached the unions, intent on winning their support. With GM gone, it was an easy sell.

Brown moved to the area in the mid-1980s, after starting with GM when he turned 18. When the automaker left town, it crushed the economy of that part of town, he said.

"Growing up, my subdivision that I moved in in 1985, I doubt it would've been constructed if General Motors wouldn't have been there," he said. "Because it was relatively close to the plant."

"The west side was the greatest benefactor of General Motors, and the greatest loser," he added. "A casual drive would prove that."

He seems right. Beyond the scant fast food restaurants and gas stations, Brown could only think of a single bar that possibly remained opened since the days when GM fired on all cylinders. Turns out, it was permanently closed.

On a recent weekday night, when workers getting off the first shift might've gone to the bar for a drink, the only nearby watering hole was deserted, save for a guy drinking a bucket of beers alone and another patron who shared stories about his chihuahua that, he swore, literally eats cash.

Brown said officials were foolish to buy into Elio Motors in the first place.

"It was never going to happen," he said.