Why The Air Force Bombarded Oklahoma City With Sonic Booms In The 1960s

The FAA attempted to rig a sonic boom impact test, which backfired spectacularly

Boom Supersonic announced last week that its XB-1 test plane broke the sound barrier without an audible boom on the ground. The startup's "Boomless Cruise" claim could be the first tangible step toward overturning the Federal Aviation Administration's 1973 ban on overland civil supersonic flights. The half-century-long ban was ultimately the result of a farcical test when the U.S. Air Force terrorized Oklahoma City in 1964. Regulators aimed to prove that sonic booms wouldn't impact everyday life in flyover country, but they mobilized the public against the coming supersonic age.

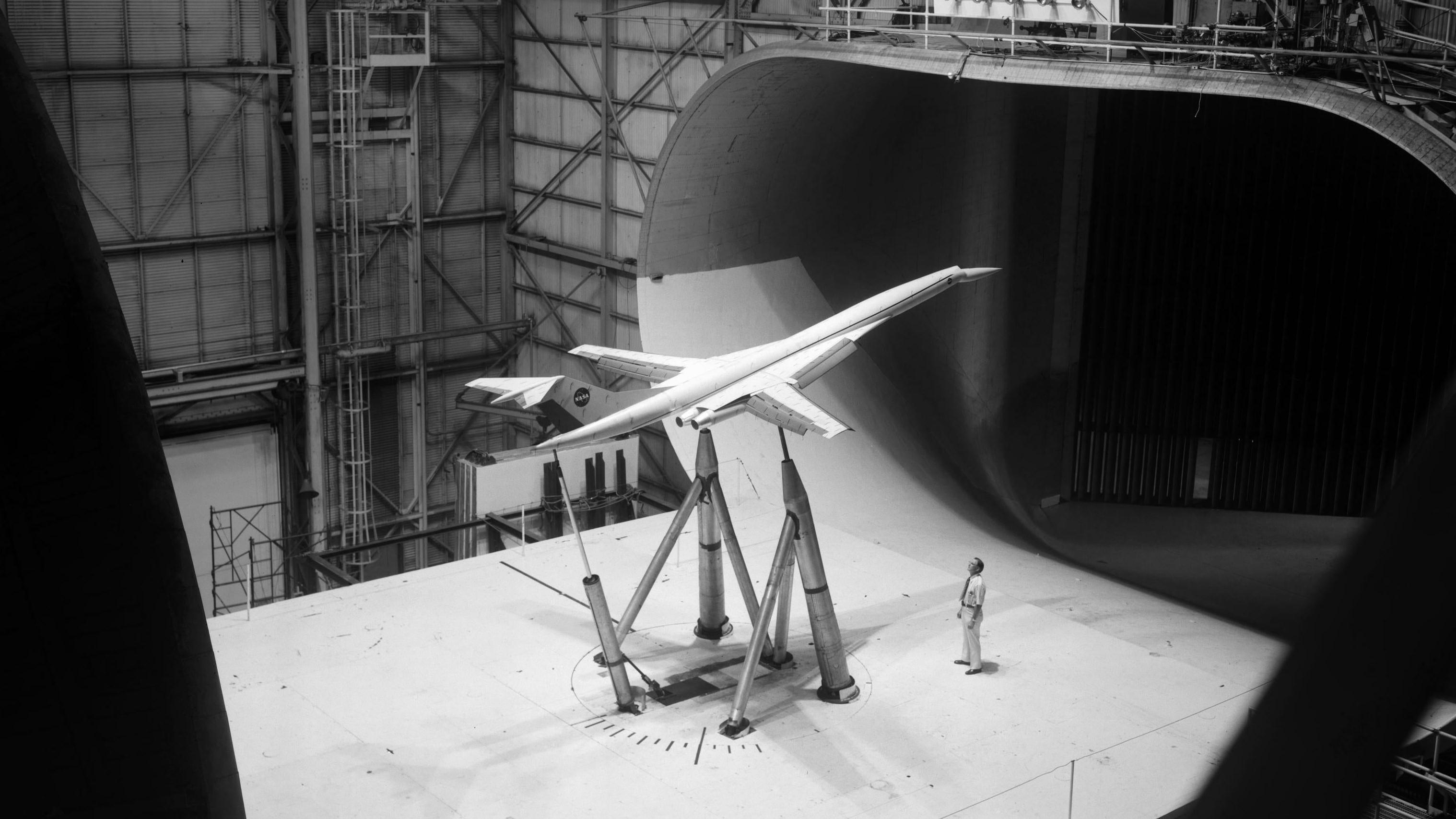

By the mid-1960s, there was a monumental rush to bring the first commercial supersonic airliner to market as a mark of national prestige and a potential money-printing machine. There were two state-backed efforts in development: the British-French Concorde and the Soviet Tupolev Tu-144. The American government was in the midst of a competition to decide on one of three potential airliners to subsidize: Boeing 2707, the Lockheed L-2000 and the North American NAC-60.

Despite the development race, no organization by 1964 had stopped to check whether regular supersonic flights were viable for the public on the ground. People were aware of sonic booms, as military jets were capable of breaking the sonic barrier for a decade. However, there was no hard data about prolonged exposure to booms. The FAA decided to organize its test to collect its own data to dissuade detractors. Yes, the agency openly stated what it wanted the result of its experiment to be. A New York Times article from January 1964 stated, "[The FAA] is convinced that the booms will not be prohibitive. Other aviation experts disagree."

The FAA chose a test location to blatantly tilt the scales in its favor. Oklahoma City's Chamber of Commerce also happily offered its city as a sacrifice on the altar of progress. The FAA and the USAF were the area's largest employers. The city was a center of the aerospace industry, with an FAA regional office at Will Rogers Airport and a major U.S. Air Force base. Despite how obvious it was, the FAA denied it tried to rig the test.

No amount of priming could prepare a population for 1,253 sonic booms over six months from USAF jets. Residents were subjected to eight sonic booms per day, and the experiment went as poorly as one would assume. Complaints flooded into the FAA. According to Time, 9,594 people complain about damage to buildings "as far as 16 miles from the flight path." The agency eventually gave out $12,845.32 to only 229 complainants for shattered windows and broken plasters. The University of Chicago conducted the test's interview survey, which found that 40 percent of people near the flight path were startled and grew to fear the sonic booms.

The public backlash grew so large that the test ended prematurely. At this point, it becomes crucial to note that the FAA never sought permission to conduct the test from the Oklahoma City Council or any elected body. The Chamber of Commerce attempted to use its political sway to prevent the City Council from telling the FAA to stop. According to the New York Times, chamber director Stanley Draper said in July 1964, "Our future as one of the major supersonic transport centers of the nation may well depend upon our acceptance of this operation." It was apparently the "patriotic duty" of the city's residents to bend over and get blasted with sonic booms.

The debacle in Oklahoma City was the first step toward the FAA's overland supersonic ban. In 1965, a judge threw out a class-action lawsuit filed by residents against the federal government because Washington claimed immunity from prosecution. During the case, Federal Aviation Administrator Najeeb Halaby resigned from his post. The decision was overturned on appeal in 1969. Halaby became CEO of Pan-Am, a prospective Concorde customer, in the same year.

Congress voted to end funding for the American supersonic transport program in 1971, which led to surviving bidders Boeing and Lockheed canceling their airliners. There was no longer any influential domestic opposition to the ban. Once the FAA imposed the ban, Pan-Am canceled its Concorde order.

Speed is the only selling point of a supersonic airliner. However, if these extremely fuel-inefficient planes are restricted to subsonic speed on most routes, they are just showpieces. Concorde was never profitable for Air France or British Airways on its transatlantic services. Subsidies from the British and French governments kept the aircraft afloat financially for decades. If the FAA does lift the overland ban in the future, it would open up a myriad of long-haul city pairings where airlines could charge five-figure supersonic airfares.