Why Siberia Drives On The Wrong Side Of The Road

It's the early 1990s. A Toyota Sprinter is wedged half-way onto a cargo ship. Its rear axle floats in the air, hovering above the Sea of Japan. A few dozen more second-hand cars from Japan are stuffed onto the vessel, some more precariously than others.

Soon these cars will arrive in the newly formed Russian Federation, where they'll be welcomed with open yet sometimes punishing arms. The majority will find loving families in the Russian far east. Others may end up in the coldest inhabited regions of the World: in permafrost-laden Yakutia and Kolyma.

A luckier few might wind up in the subtropics of Sochi, among palm trees and pebbly beaches. Only time will tell, and only one thing is clear: none will return to the orderly thoroughfares of Japan ever again.

The cargo ship inches closer to its destination: the port city of Vladivostok, where seven decades of automotive isolation have come to an abrupt end. Demand for cheap cars is skyrocketing.

Five hundred miles to the east of Vladivostok lies the coast of Japan. There, stringent vehicle inspections and parking regulations have contributed to a surplus of used cars in desperate need of adoption. Very high-quality used cars.

Supply meets demand and, in the wake of the Soviet Union's demise, a massive car shipping industry is emerging.

The vessel makes landfall in the Free Port of Vladivostok, where the precious automotive cargo is unloaded. Many of the cars are funneled to the "Green Corner" on Vladivostok's outskirts, where all imaginable forms of JDM cars can be found: adorable kei trucks like the Subaru Sambar, regal executive sedans like the Nissan Laurel, bulletproof off-roaders like the Land Cruiser 70.

Since the early '90s, millions of right-hand-drive cars from Japan have found their way into Russia, a country that drives on the right side of the road, just like the U.S. and totally opposite from Japan.

That is to say, for these cars, they're going to operate on the wrong side of the road than what they were designed for.

The JDM import industry in Russia peaked in 2008, when over 500,000 second-hand vehicles from Japan were imported. Since then, economic and legal factors have dented the trade, which has declined "ten-fold" in recent years. Unsurprisingly, rumors float that the era of right-hand-drive is slowly coming to an end.

But you wouldn't get that impression in the contemporary Russian far east, where 84 percent of traffic is right-hand-drive. That's 84 percent of 835,000 registered vehicles all driving on the wrong side of the road, according to 2017 AVTOSTAT figures.

This means that the Russian far east is perhaps the only large part of the world (hi there, U.S. Virgin Islands!) where the vast majority of cars has steering wheels on the—for lack of a better term—wrong side. Though motorists in the Russian far-east would beg to differ. To them, right-hand-drive is much more than an awkward driving position.

Vasiliy Avchenko describes this phenomenon in a fascinating Russian-language column, noting the culture stemming from the "era of right-hand-drive" in Russia's far-east. In one such poem, written by Ivan Shepeta, there's a telling line: "my steering wheel is on the right, and my heart is to the left." Apparently, there's also a "Right-Hand-Drive" beer now available in Vladivostok.

Avchenko himself wrote a 366 page novel novel titled "The Right Wheel."

Right-hand-drive culture is by no means exclusive to the Russian far east. But the farther west you go in Russia, the less JDM you'll find.

I'm writing this article from Saint Petersburg, which is just about the westernmost city on the Russian mainland—a 5,900 mile drive from Vladivostok. Almost all of traffic here is left-hand drive, and therefore boring.

I set out thinking that I'd struggle to find this right-hand-drive culture out here—that it would be easier for me to travel 2,000 miles to Llanfairpwllgwyngyll, Wales, and report on castles and sheep instead.

I was very wrong. Here's what I found:

I got in touch with a gentleman named Vitaly, who owns a very Jalopnik car: a 1988 Toyota Crown Wagon (GS136V), with a four-speed manual on the tree, a bench seat in the front, and, of course, right-hand drive.

Vitaly comes from a right-hand-drive family, which, in Saint Petersburg, is kind of weird. His wife drives a Nissan Serena Rider Autech 4x4—a tall and graceful minivan not unlike the Toyota Alphard. As Vitaly tells me, she's only ever driven right-hand-drive cars and "categorically refuses to even try" left-hand-drive.

In a way, Vitaly and his wife reflect the mainstream right-hand-driving Russian. They appreciate their cars for the comfort, reliability, and affordability, paying little attention to the awkwardness of steering where the front passenger should be sitting. For them, these cars are, foremost, utilities, not objects of petrol-headed adulation.

When I asked Vitaly how he felt about driving a right-hand-drive car in right-hand traffic, he gave me an oblivious shrug. "Eh," he said. "You get used to it in a few days."

I'd managed to scratch the surface with Vitaly, but I wanted to get a sense of the folklore surrounding right-hand-drive. In the left-hand-drive stronghold of Saint Petersburg, this meant diving into the JDM underground.

In the midst of an early March snowstorm in Saint Petersburg, I received a phone call. A friend was going to pick me up and take me to a meet-up of what he called "JDM junk." This sounded promising.

Well, the event was sort-of underground, but, at the same time, not underground at all. To the extent that the event was held in an underground parking lot of a busy shopping center, it was indeed underground. However, the shopping center actually allowed this congregation to take place, and during peak shopping hours. If you're approved by the authorities that be, how underground can you be.

But it was still totally ridiculous. It was amazing, actually.

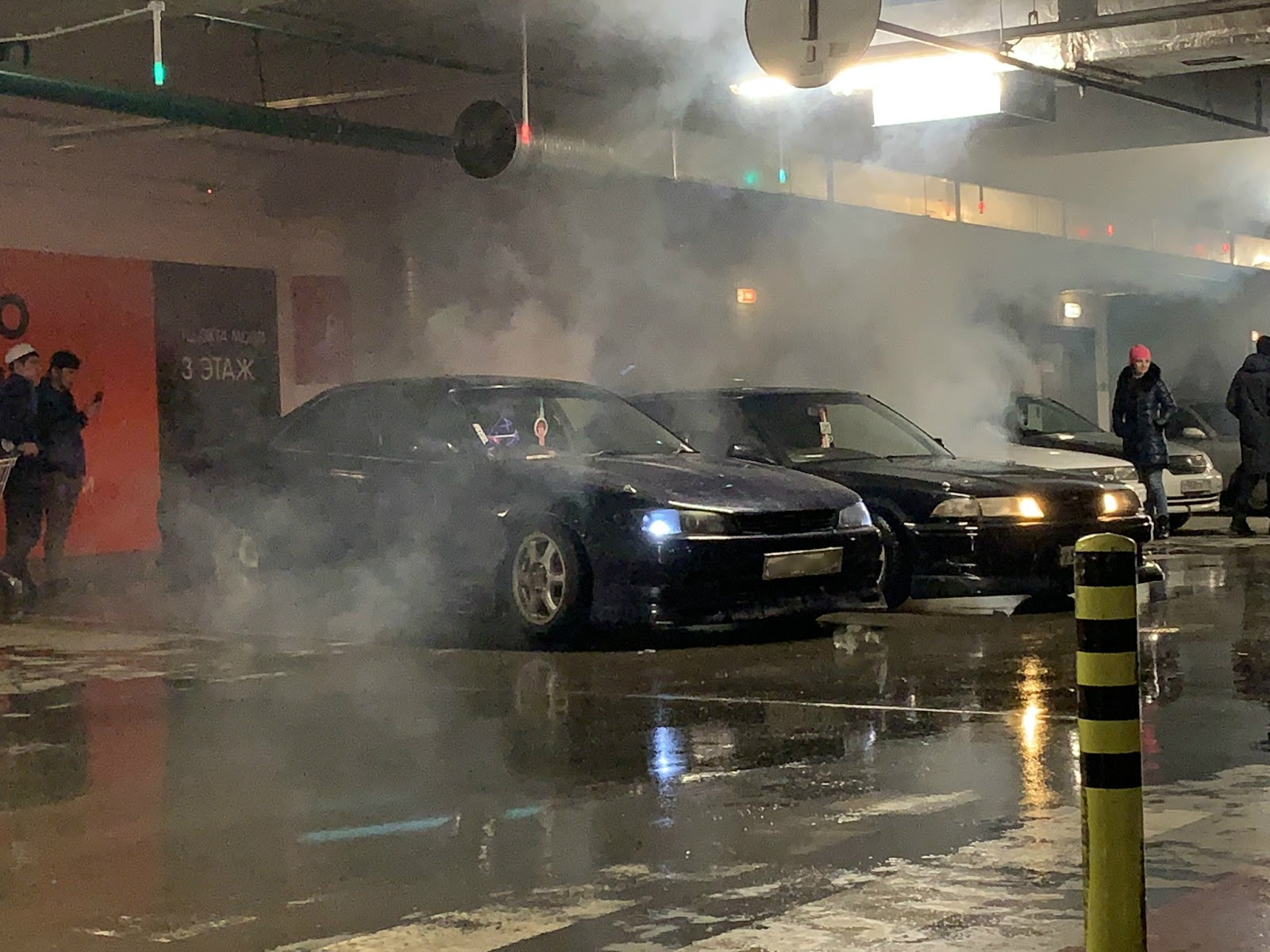

Straight-piped Skylines fought for parking spots with confused and frightened weekend shoppers. All the engine farts and exhaust fumes marinated in the confined quarters of the lot.

There was an army of JDM Nissan Cubes. One of them had all this fake metal patina and barbed-wire wrapped around its plastic grille.

There was a Toyota Aristo (similar to an early-2000s Lexus GS) wrapped in highly suggestive anime, parked next to a Lada with a missing headlight. It's itasha, if you're curious.

There were cars so relentlessly chewed up and spit out from perpetual hooning, that they developed this callous layer of dust and grit. It was, for some reason, deeply satisfying to behold, like a broken-in baseball glove is soothing to the palm.

Somebody brought a katana. As you do.

It was nice to see members of the Eurotrash delegation in attendance, like this Opel Ascona parked alongside an R33 Skyline.

So too was therea E60 BMW 5 Series that photobombed one of my shots, although this could have been an unwitting shopper desperately trying to find a way out.

I couldn't take my eyes off a super-mint Toyota Crown Super Saloon V8 from the '90s, which the owner, Yaroslav, claims has less than 40,000 miles. It certainly looks the part.

Yaroslav kept telling me of his right-hand-drive adventures. About how he has to "reverse through the McDonalds drive-thru" and drive around with an arm extender so that he can pay tolls.

Max, the owner of an early '80s Toyota Cresta, more clearly explained the distinction these cars had against the left-hand-drive norm. He told me about his long search for a vintage JDM car and how "back in the day, JDM cars were built for people," meaning that "they weren't meant to be disposed of in just a few years."

Our conversation was cut short by an uncanny cacophony. At one end of the garage there was a Mazda 3 hatch, blaring high-octane dubstep through a military-spec subwoofer. The dubstep was occasionally interrupted by an MC who, through relentless microphone feedback, tried to bring a semblance of order to the event. The MC would, in turn, be interrupted by a redlining straight-six in the distance. In an underground parking lot, it's as abrasive a noise as a space shuttle breaking through the earth's atmosphere.

Then came the burnouts.

The tire smoke, in combination with vape clouds, degraded the air quality to public-health-crisis levels. It was, at that point, prudent that the event move somewhere else.

The cars ventured almost halfway across the snow-covered city to a new, above-ground location. At an empty mall parking lot, the JDM crowd converged with an indigenous Saint Petersburg car scene: the Lada drift people.

The snowstorm had passed and the temperature was falling, yet the communal festivities continued. The Mazda 3 MC assumed his place in the center of the crowd, now blaring a more diverse selection of thumps. J-Trance reverberated into the snow.

At one point, the MC challenged everyone to a revving contest, and an orchestra of redlining Toyotas ensued, complete with 2JZ trumpeters and contrabass 1UZ V8s.

Meanwhile, a makeshift drift circuit assembled on the perimeter of the lot. Ladas and Skylines and Crowns slid gracefully in tandem, spooling up clouds of powdery snow.

I stood there, slowly losing my hearing from the noise and the feeling in my fingertips from the cold. My quest to locate the elusive 'right-hand-drive' culture of Saint Petersburg was complete.

As the night went on, more and more diverse JDM filled up the parking lot. The scene began to resemble that "Green Corner" car market in Vladivostok—where a fair share of these cars likely began their journey through Russia. And I couldn't help but envision some of them wedged half-way onto a cargo ship—their rear wheels pointing into the air, hanging above the Sea of Japan.