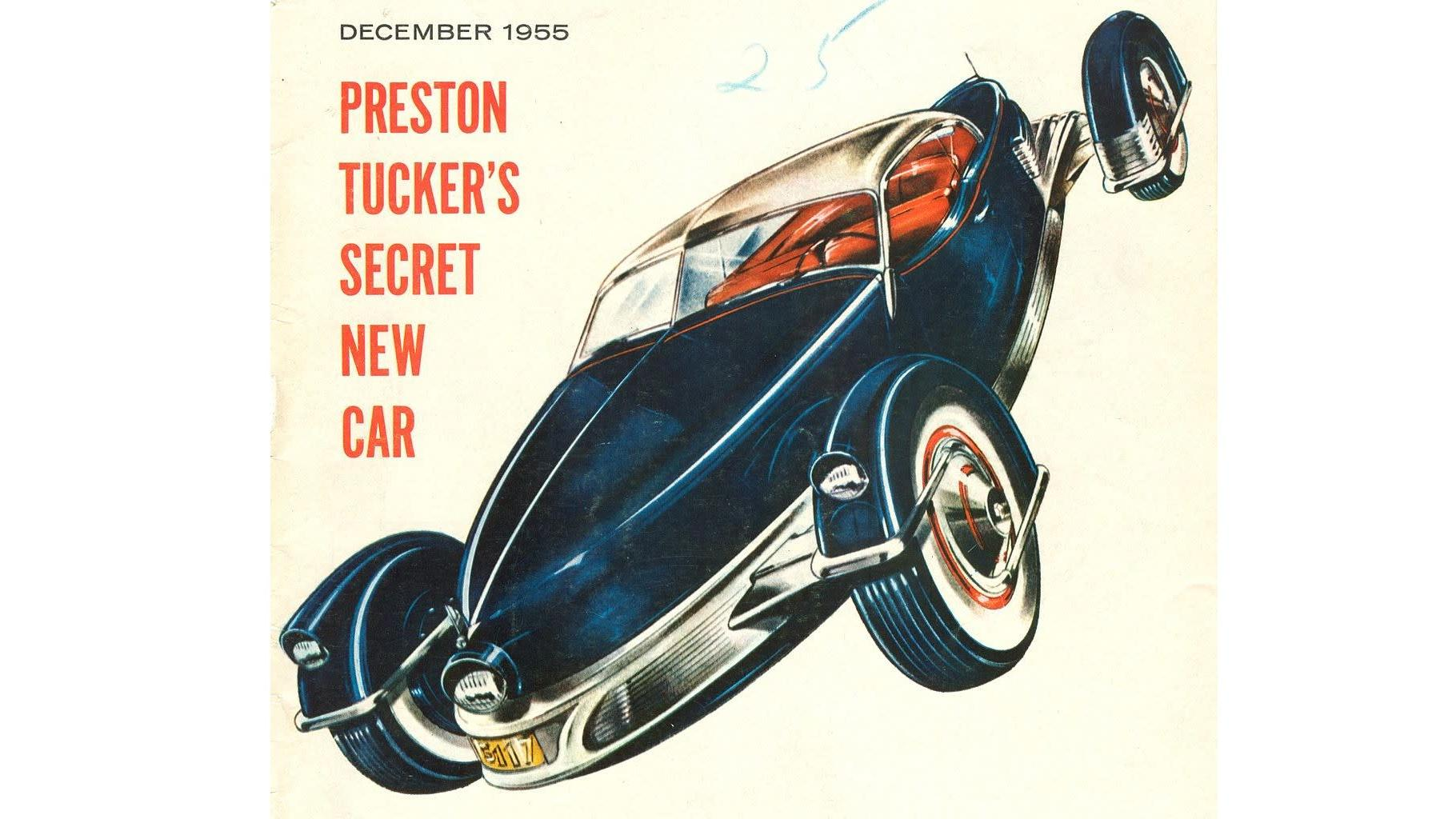

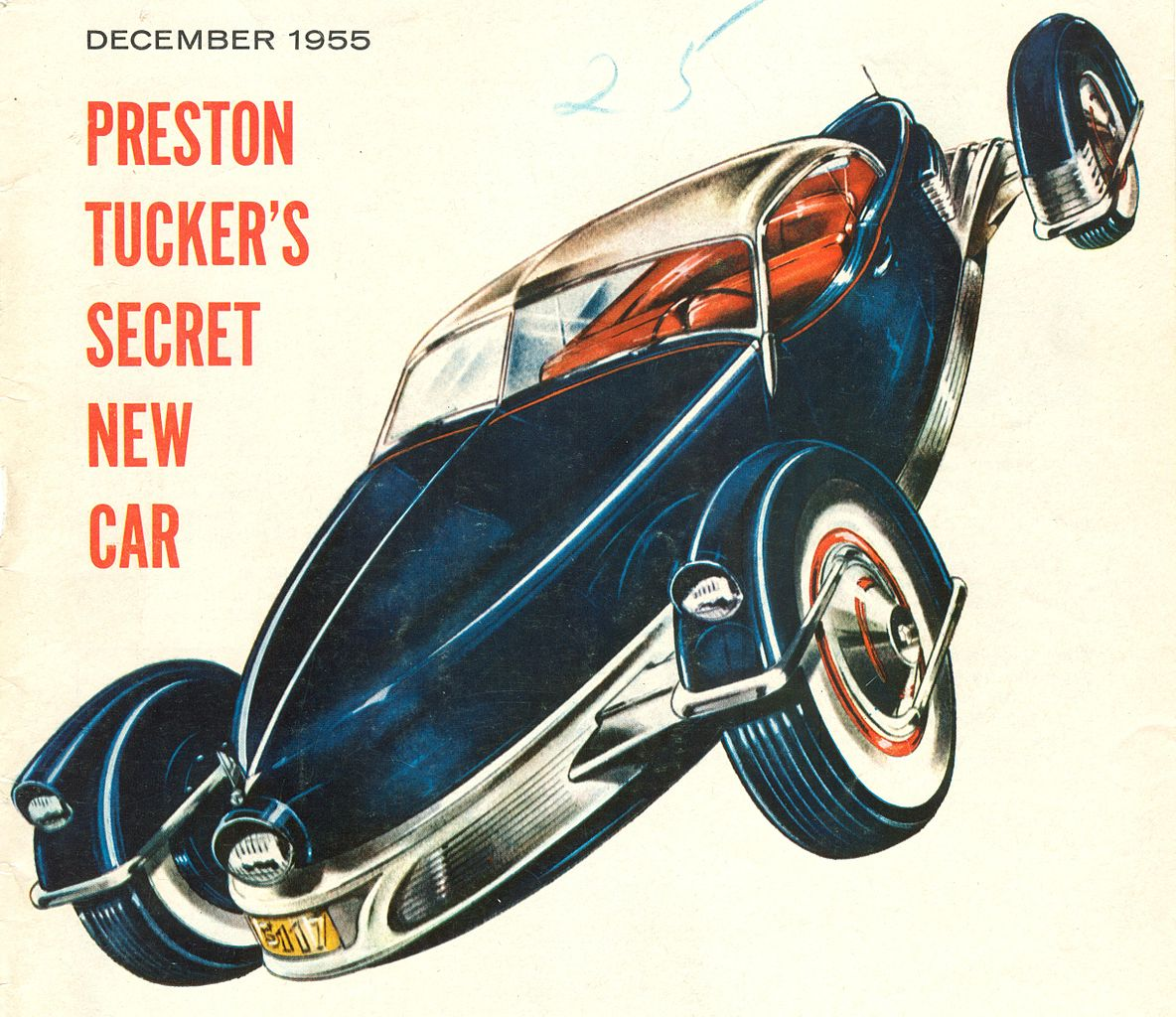

The Tucker Carioca Deserved Its Day On The Road

No one was quite sure what to make of carmaker Preston Tucker in his day. He was trying to design revolutionary vehicles that would have outshined the Big Three (if only they had worked), but his ultimate failure led a lot of folks to believe he was just a grifter looking for a quick way to make a buck off of prospective investors. But after seeing the Tucker Carioca, I'm more inclined to believe Tucker never got the chance he really deserved.

At first glance, the Carioca looks a little bit like a classier Plymouth Prowler. It has the sleek lines of an early-1950s roadster without any of the clunkiness of the Prowler; the exposed wheels jut out from a front and rear end that are whittled to an attractive point. It was kind of like what would have happened if someone closed up an open-wheel racecar of that era.

Tucker didn't design the Carioca himself; that was done by Alexis de Sakhnoffsky, who approached Tucker about putting it into production. By the time Tucker heard about the thing, he'd faced countless lawsuits and had been hounded by creditors for years, but he still had his plant in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and he hadn't given up on his dream of designing a mass-produced car.

So, the Carioca was ultimately made to utilize as many of the parts that Tucker still had laying around the shop or that could be purchased elsewhere, since there wasn't the time nor the funding to manufacture things in-house.

It was also designed to be a kit car, which Tucker thought would be easier for the American public to digest. Buy the car for $1,000 and put it together yourself–or pay a $60 fee to have a certified Tucker mechanic assemble it for you!

Just like his Tucker 48, this car was still designed with tons of neat innovations that were designed to make a lasting impression on the auto industry and change the way we considered cars. The stuck-out wheels came with removable fenders that would be easy to clean, in part because Tucker claimed he'd conducted research that suggested the average car carries 10-12 pounds of gravel around in its wheel well. Those fenders were fitted with headlights that pointed in the direction of the tires, while there was also a fixed headlight on the front end.

Like his Tucker 48, the Carioca had an engine in the rear and a very simple dash panel with a speedometer and four blinkers that would let you know the state of your oil, fuel, temperature, and amperes (or, electrical current). He was advised by racing driver Harry Miller that a pointed tail was a plus for a fast car, so he included that, too.

The Tucker name had become fraught with controversy—and was also unavailable for his use, as it had been purchased by Dun and Bradstreet—so it was difficult to find anyone in the United States who would give Tucker a chance. The president of Brazil at the time invited Tucker to build his factory there, so Tucker made several trips there to see how things looked.

Unfortunately, it wasn't to be. Exhausted by his travels, Tucker returned home to learn that his fatigue was unnatural indeed: it was lung cancer. In 1956, he died from pneumonia, a complication of cancer.

So, the plans for the Carioca were shelved. That is, until Rob Ida Concepts picked them back up.

After getting their hands on some original designs, the New Jersey-based custom vehicle design company set about translating those drawings into others that were eventually put into Solidworks. The group then started procuring different parts to be used in recreating the machine. They eventually brought it to life in a virtual 3D capacity, which made it easy to explore the details of the machine in depth and close to real life for the first time.

I still think the Tucker Carioca deserved its day on the road. I don't necessarily think it would have been a big hit or that it would have wholly succeeded where its predecessor failed. But it was one hell of a gorgeous machine, designed with Tucker's 48 disaster in mind—I can assume it would have had fewer teething problems, and it could have been a great racer if only it had the chance to get out on the track.

Now we can just hope someone will bring it to fruition in the real world, not just in a virtual format.