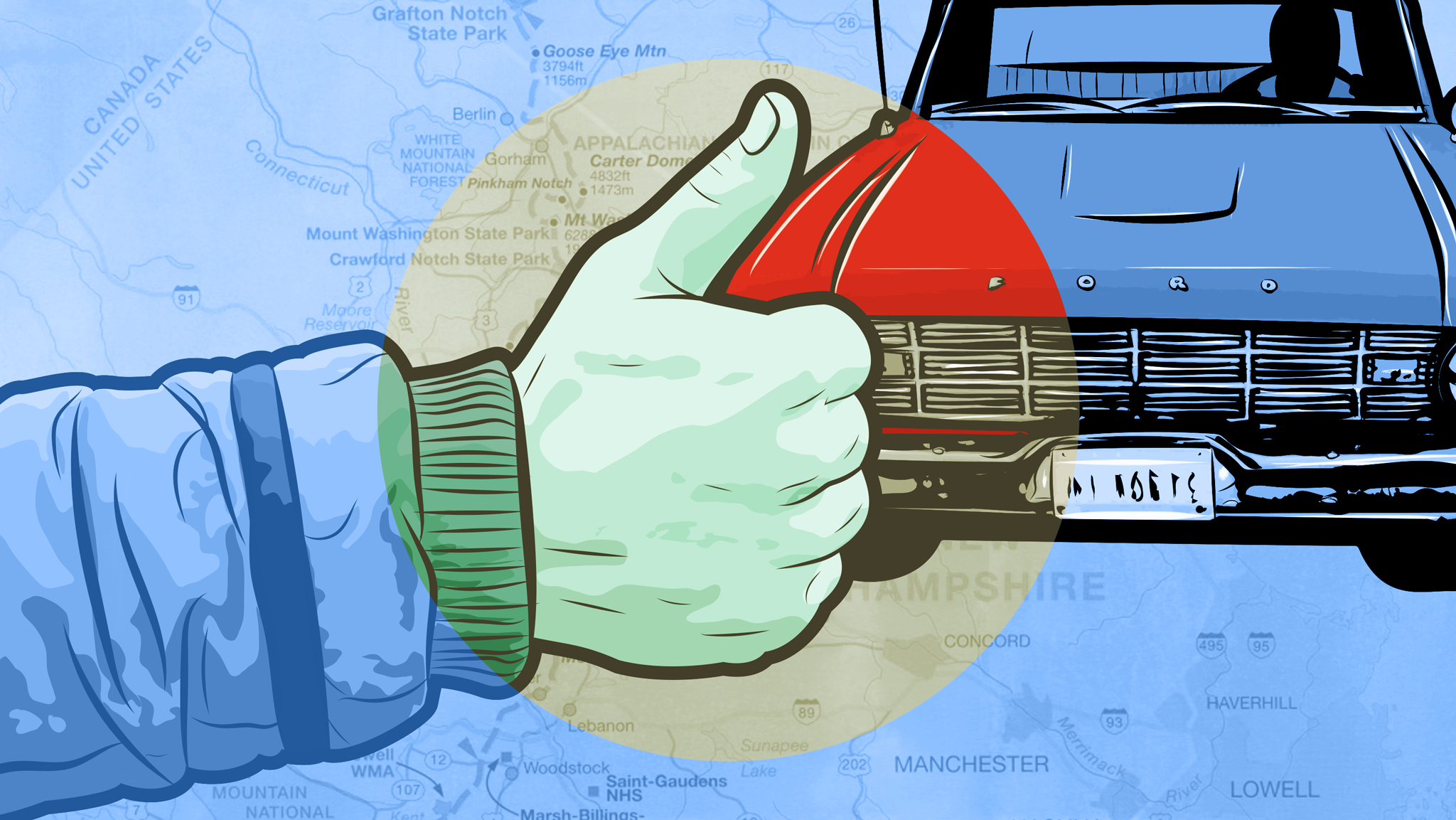

The Summer I Spent Picking Up Hitchhikers On The Appalachian Trail

I picked up hitchhikers all summer. Here's what happened.

This story begins June 30, 2016. Pennsylvania builder Bruce Henn finished Regular Car Reviews' project car "The Vagabond Falcon," a 1960 Ford Falcon four-door running on a 1993 Fox-body driveline. My job was to put miles on the Vagabond Falcon and gently break it in with a mix of city and highway driving.

I picked up hitchhikers to do this.

The hitchhikers were all Appalachian thru-hikers; modern monks walking the approximately 2,200-mile long trail from Georgia to Maine. The Appalachian Trail passes through Pennsylvania near Bruce Henn's Garage in the adjacent town of Port Clinton.

Port Clinton is an old canal and railroad town near the intersection of Pennsylvania Route 61 and Interstate 78—approximately four hours west of New York City (by car) and two hours northwest of Philadelphia. Port Clinton has one main street about one-third of a mile long, and about five cross streets only 100 yards long. Its local economy includes:

-

One rail yard

-

One barbershop

-

One bar

-

One volunteer fire company

-

One soda vending machine located in a resident's front yard, and

-

One high-end BMW motorcycle dealership attracting wealthy out-of-towners zooming around town on $18,000 touring bikes

For me, the most important landmark in Port Clinton is St. John's Pavillion, an open-air structure covering a generous 1,000 square feet. "The Pavilion" is free to use by any thru- or section-hiker seeking a roof to sleep under as they traverse the Appalachian trail. Across the road from The Pavilion is a camping area, for those who prefer the privacy of their own tents, and a brick stove for cooking.

There are other shelters along the Pennsylvania section of the Appalachian Trail (501 shelter, Eagle's Nest, Eckville Shelter) but none are as large as the Port Clinton Pavilion. Hikers commonly spend two or three nights there, resting, socializing and hitchhiking two miles south on Pennsylvania Route 61 to the Tilden Shopping Center to re-supply at Walmart, and replace broken camping equipment and tools at a Cabela's.

Every few days, I would cruise the Vagabond Falcon along Route 61 looking for outstretched thumbs and backpacks. If I found none, I would hang out at the Port Clinton Pavilion and hear their stories in exchange for rides.

(To protect the innocent and the guilty, names have been changed.)

June 30, Port Clinton, 11 a.m.

I rolled up to the pavilion in Vagabond Falcon. Eight hikers milled around inside the Pavilion. Parking the old car in a dirt turnaround, I walked up the four concrete steps in front.

"That your car?" one hiker asked.

"Yep," I said, holding up a green Coleman jug, "I brought some water if you need to top off."

"Oh, right on!"

The first hiker I met that day went by the trail name "Cargo." On the AT, folks rarely use real names. Like Fight Club, who you are on the trail is not who you are in real life. Cargo was a man in his early 40s, wearing a patchy mustache and self-buzz haircut. Cargo said he could use a ride to the Lowe's, a big box hardware store, to look for work.

"I have 15 years of construction experience," Cargo told me. "Up there there's gonna be a foreman pissed off at one of his guys, guarantee it. I'll go up to him and take that guy's place for a few days."

On the AT, folks rarely use real names. Like Fight Club, who you are on the trail is not who you are in real life.

Cargo's approach to thru-hiking was atypical. His plan was that he would hike for a week, stop in a town and scab as much work as he could. Most thru-hikers had money set aside for the trip. Other hikers told me that the minimum fund for an AT thru-hike was $1,700. Cargo was penniless and his backpack frame was broken.

"My wife threw all my stuff out of the second story window of my mother's house and stole my table saw," said Cargo. "My backpack must have broken then."

"Was that before you set-off?" I asked him.

"Yeah."

"And you've been hiking with a broken frame this whole time?"

"Yeah, I was an emancipated child."

I didn't know what to say to that, so I searched the Falcon's trunk and found some J&B Weld for Cargo's backpack frame. He told me that he was at Lowe's yesterday and a cashier told him that a construction company in Hamburg is hiring and maybe he could get temporary work there.

Cargo and I hopped in Vagabond Falcon and drove into the town of Hamburg looking for this construction company at the address Cargo had written on a scrap of cardboard. As we drove through stop-and-go traffic, the Falcon's brakes squeaked at every stop.

"You have air in your lines," said Cargo from the passenger side of the front bench seat. I used to be a mechanic for seven years. Yep, you have air in your lines. If you have tools back at your house, I could come to your house and we can fix it! I can do it fast!"

"Thanks for your offer, but I have a guy," I said. I pumped the brake pedal at a stop and it felt firm. No spongy feeling.

"Here's the address, nothing here," I say, "Unless they're running a construction business out of that house." We were stopped in a suburban cul-de-sac.

"That clerk was telling stories," Cargo said flatly.

I ratcheted the Falcon's B&M Megashifter into reverse and pointed her sunburnt hood back in the direction of Port Clinton.

1 p.m. Port Clinton Pavilion, same day

A handful of thru-hikers gathered around a communal box of donuts and store-brand water bottles at a picnic table under the pavilion. A thin thru-hiker named "General Tsu" had dark red bruises and cuts on his forehead, just above his left eye. He wore an unbuttoned shirt, exposing his hollow chest. The previous night, according to General Tsu himself, he drank all the rum he could and fell flat on his face. Wherever he landed, he slept.

Above our heads, birds flew about the rafters of the Pavilion. The small brown birds built nests up there. If you watched, you could see wiggling baby birds eager for sustenance. White islands of bird poop blotted the Pavilion's wooden floor. Hikers pay the birds and their droppings little mind. By the end of the day, thru-hikers are mentally and physically drained. All they desire is food, water, carbohydrates, protein, and maybe booze and/or weed.

But hiker exhaustion isn't a hard and fast rule. There are some hikers who arrive at Port Clinton rejuvenated and ready for more activities. I watched two built girls arrive at the Pavilion, drop their packs, spread yoga mats down on the grass, and get to stretching.

Cargo resolved to fix his pack's frame with more than just J&B Weld, and he was using everything he could get his hands on. Band aids, post-office mailing tape, clear epoxy. It wasn't going well.

SNAP. His pack's frame breaks further.

"SONOFABITCH!" Cargo yelled. He threw his pack's frame down and stomped around the Pavilion's floor. "I'm going to go down to Dalton, South Carolina and shoot a motherfucker!"

The Yoga Girls stood up, gathered their mats and packs, walked across the road and set up on the grass lawn by the brick grill, far away.

I quietly gathered my notes and carried them out to Vagabond Falcon's trunk.

"Sorry for getting worked up," Cargo said.

"Don't worry about it," I said, and left. My Walker Quiet-Flow muffler hides the Ford 5.0's telltale growl unless I stand on the throttle. Cargo returned to his backpack troubles and I drove home, the single exhaust dump puffing a soft gurgle.

July 3, 183-Crossing

The Appalachian Trail crosses Pennsylvania Highway 183 approximately fifteen miles north of Port Clinton. No amenities lie at this crossing. Hikers only find a dribbling spring about a quarter-mile off-trail and a local Trail Angel who restores a cooler full of "Trail Magic"— food and band aids to help hikers along.

I parked the Falcon up against a grass hill. There was no designated parking, only a dirt lot with "No Parking" signs. I'd never seen parking enforced here. The dirt lot connects to a fire trail. I suppose the state wants the lot clear so fire jeeps can reach the game lands about two miles from Route 183.

Hikers arrived piecemeal.

When two Crown Victoria police interceptors and a GMC ambulance arrived at her elderly parents' house one night, Stevie Nix bought the biggest camping backpack she could find and hit the AT.

"Ezekiel." An older gentleman who has hiked alone since the Georgia border, started at Springer Mountain with a friend but that person got tendentious and dropped out for clear reasons.

"I'm a contractor," Ezekiel said, "and I quit my job after I got on the trail. I just called-in and told him [boss] that I'm done."

"Stevie Nix." A solid-looking woman in her early 50's who sweated enough serotonin and dopamine to cure every case of depression at PAX-East.

"How far have you come?" I asked her.

"Since the beginning!" she said while smiling, and holding her arms out. "Since the very beginning and I feel FAN-TAS-TIC!"

Stevie Nix told me that her family members back home in Kentucky were in a protracted feud with each other. The fighting went on for years for reasons that are too grim to report here. She told me what happened, but I can't bring my fingers to type the sentences. When two Crown Victoria police interceptors and a GMC ambulance arrived at her elderly parents' house one night, Stevie Nix bought the biggest camping backpack she could find and hit the AT.

For Stevie Nix, the Appalachian trail worked better than any therapist. She was happy now and eagerly hung out at my car, enjoying juice boxes and snacks my friend Carrie brought.

"Eyes Down Kid." This young man wasn't a thru-hiker. I never got his name so I made one up. He was a late-single-digit boy walking southbound on the AT with his Oakley-wearing, attaboy-chanting, tight-black-t-shirt-flexing, fit-bit-bracelet-checking dad. "Eyes-Down-Kid" was still growing into his ears. Stevie Nix congratulated him on hiking just like the big kids. "Eyes-Down-Kid" picked his eyes up off the trails for two Mississippi-Seconds, looked at Stevie Nix, then looks back down at the dirt and rocks. His Touchdown-Father grinned.

"Party Sub." Male, early 20s, ukulele strapped to his pack. Party Sub's pack was from the 1980s. Its design features a fully external tube frame. Party Sub said he makes extra money on the trail by busking outside Walmarts.

"Moth." Male, late 20s or early 30s—hard to tell. Moth had a shorter beard than most other hikers. He wore modern hiking clothes made by brands like Under Armor and Reebok. On his back was a high tech Osprey Pack, the Tesla of hiking gear. Moth was very open about his former profession.

"I was was a light-tech on Spielberg's Lincoln," Moth said. "I spent most of my day up in a crane adjusting lights. I'd be up there for hours. Tinder helped pass the time."

I believed Moth. I believed he was telling the truth. But why did I believe his story about working on a major motion picture, and not Cargo's story about being a mechanic? Why did I leave Vagabond Falcon unlocked around Moth and locked around Cargo?

Calmness. Moth didn't try to impress me. He didn't try to convince me that he had film industry credits.

"Did you see Spielberg?" I asked.

"Yeah, but only from up in my crane," Moth told me.

"I want to get you lunch, what do you feel like?"

"I could go for a burger, honestly. I haven't had one in a while."

"If you get from here [183-crossing] to Port Clinton tomorrow, I'll meet you at the Pavilion and we can go to Five Guys."

"Okay," he said.

July 7, Five Guys Burgers and Fries, Tilden Shopping Center, Hamburg, Pennsylvania

Moth and I parked the Falcon in the Tilden Shopping Center, a monument to cheap land prices and commuter communities. In addition to Cabela's, the center provides a Lowes, a Walmart, an Army Surplus Store, and a school of smaller businesses all trailing like pilot fish following Big Daddy Shark Cabela's, gobbling up crumbs and scraps.

Moth and I were, with the exception of three pre-teens, the thinnest people in Five Guys.

Parents told their kids to sit down and behave. Grandparents looked into their fries and lamented the years. Daughters rolled their eyes, wishing the world would disappear. Fathers began sentences with "We gotta...", "You have to...", "Then we will...", and "You must..."

Moth and I sat far from the crowd, near the door where I could keep an eye on the Falcon. Moth ate his burger slow and deliberate, placing the meat-mass back down on the plastic tray between every bite.

We were on no schedule. We didn't "have to" anything like the teens did.

"Either you make time (on the Appalachian trail) or you don't, neither is important," Moth said. "Oh, someone is checking-out your car."

I looked. Two gray-haired men wearing tucked-in light-colored plaid shirts, blue jeans, and white tennis shoes walked around Vagabond Falcon, pointing at different parts of the car. One of the men knelt on one knee to look under VF's front bumper. Unsatisfied, the man lowered himself prone; flat on his belly. I wondered how hot that asphalt was. He tilted his head from side to side like a confused husky dog. Meanwhile, his boomer friend cupped his hands around his eyes and looked through the passenger window.

"I think they're figuring out that it's far from stock," I say.

"Do people do that a lot?" asked Moth.

"Oh yeah, but I don't mind, she's meant to be enjoyed."

Moth and I finished and left. The gray-haired men had left, but saw us leave from the far side of the parking lot. They stared.

July 11, 183-Crossing

"Double Knot," or "DK." Male, late 20s. Experienced hiker. Already completed the Pacific Coast Trail. He moved fast and is very well kitted-out, even more than Moth. DK is an electrical engineer. He saved up his pay for a year before setting out on the AT. He carried a bear-proof food canister. It was an egg-like black case with no sharp edges. If a bear can't claw open a container, it will usually try to bash it until it breaks. A bear-poof canister will bounce away, rather than crack. DK also carries a canister of bear-spray on his belt.

"We're often mistaken for homeless," DK said. Like Moth, DK doesn't have the gaunt and world-weary look that so characterizes northbound thru-hikers by the time they arrive in Pennsylvania. Money helps. Double Knot has enough to eat hardy.

"What is that blinking box on your pack's shoulder strap?" I asked.

"Transponder," DK said, as he unclipped the orange and black device and handed it to me. It looked like a garage door opener with a few extra buttons. "Every hour or so this uploads my GPS coordinates to a website. It also sends and email to my friends and family telling them where I am."

"What does this S.O.S. button do?" I asked.

"It empties my bank account!" he said with a laugh. "It rings 'GEOS,' an independent search and rescue company which will contact whatever emergency services are close and give them my coordinates to come find me, including life flight... I think... not sure. I've never pressed it.""Wow."

"Don't press it."

"I won't."

"Yeah, this transponder is a subscription service that costs $170 a year."

July 12, Port Clinton Pavilion

A big gang of hikers was at the Pavilion this day. The Vagabond Falcon turned heads rolling up. I gave a lot of rides to different people:

"Colt." Male, beard, from Boulder, Colorado. Worked as a cattle hand. He moved to Los Angeles to write for the LA Times, but now he freelances.

"Rumblejunk." Male, bigger beard than Colt. Has a podcast at soundsofthetrail.com. He carries an ink-stamp which made a red impression of his face. He used the stamp in-lieu of a signature when he signed logbooks.

Each shelter along the Appalachian trail has a logbook. Some are simple school composition notebooks. Others are more elaborate three-ring binders or professional-looking trapper keepers.

"The worst feeling is mice crawling on your face while you sleep," Rumblejunk said. "That's why some people set up tents on the other side of the road."

When a hiker arrives at a shelter, it is customary to leave a journal entry telling of the day's events (if any) and a thank-you to the shelter's caretakers.

"Galapagos." Male, looks like Jamie from Mythbusters. He was a teacher, and didn't say much.

"Cinder." Male, thin beard. He earned his name after partying too hard and falling into a fire pit, he said.

"Spicoli." Male, clean shaven hiker from Tennessee with shoulder-length blonde hair and a build like a varsity gymnast. He was joyful and eager to talk. Over the following two days, Spicoli gave me the most complete interview of any hiker on the trail. More on that later.

"Refill." Male, a tourist from northern Germany. He flew to the U.S. just to hike the AT. Refill had to hustle because his visa was scheduled to end on September 20, leaving him just over two months to walk from Port Clinton to the AT's northern terminus at Mount Katahdin in Maine.

My Snap-On magnetic shop light hung from one of the ropes strung up on the Pavilion's ceiling joists. Hikers suspend food bags from ropes so rodents have a harder time finding the goods. Crushed beer cans were fixed halfway down the ropes, to further aggravate any critter brave enough to scurry down.

"The worst feeling is mice crawling on your face while you sleep," Rumblejunk said. "That's why some people set up tents on the other side of the road. You get privacy and bugs and mice can't get at you...but I'm sleeping in the Pavilion tonight."

The sun went down completely. I told the gang I'd return tomorrow. Spicoli and others wanted resupply rides.

July 13, 10 a.m., Port Clinton Pavilion

Thunderstorms were in the forecast this day. Most of the hikers stayed under the Pavilion's roof. Around went a collapsible bong. I took a very small hit, out of courtesy.

"Erin." Female, possible townie. Late teens or early 20s. Erin showed up about 30 minutes before I arrived in the Falcon. She wore a tie-died sundress which was hemmed above the knees. On her feet were generic-looking work boots, Columbias or maybe Red Wings. Erin brought a box of french fries for all the hikers to share. The fries were thick-cut steak-fries from a family restaurant just north of Port Clinton, the type of fork-and-spoon diner where your grandparents like to eat, talk, and agree that all teenage boys belong in jail, except for Tom Williams' son, he's a nice boy.

Erin drove an early 2000's silver-gray Chevrolet Cavalier with factory alloy wheels and a deck spoiler. The front clip was cracked and rashed from either a low-speed accident or parking mishap. Erin sat at the picnic table and talked to Rumblejunk while twirling her hair. She asked him when he tried his first beer. Rumbejunk said he didn't remember. Erin smiled with a slightly open mouth. Rumblejunk added plainly that alcohol wasn't that important to him.

"Hold on, Hold on," interjected Michigan, "have y'all ever smoke crack?"

Around came the bong. Thru-hikers rarely carry any liquid other than water. Alcohol is a great deadener but it is too heavy, even in plastic bottles. Every ounce counts. Cannabis is much lighter and its pain-relief-to-carry-weight is better suited to hiking.

The sun was getting lower in the sky and some hikers were still arriving. An older man with a tight crew-cut and light blue eyes trudged up the Pavilions concrete steps.

"The post office lost my mail-drop!" he announced to everyone and no one.

A mail drop is when you, as a hiker, mail yourself a package to your future self strategically up the trail. Some hikers do this before the even begin a thru-hike. Hikers will pick towns along the trail, fill a box with non-perishable foods, and mail the box to a Post Office in a town in which they know they will pass in the coming months.

"You can have some of my oatmeal," Turtle said.

"I have extra instant coffee I'm not going to use," said another voice.

"Oh, I got it," said the crew-cut-man, holding up a Flat Rate USPS box, "she [the postmaster] had it, she just lost it. As dumb as she was, I'd be all over that like a bad rash!" he added.

The portable bong bubbled. No one had a response.

We (the other hikers and I) began calling crew-cut-man "Michigan" behind his back, because he repeatedly said he was from Michigan, even though his accent put him square in Kentucky. Michigan told us he worked at a United Auto Workers plant for 30 years up in Detroit, "doin' brakes."

"Hold on, Hold on," interjected Michigan, "have y'all ever smoke crack?"

All conversations in the pavilion stopped. Everyone looked at Michigan.

"I'm from Michigan, I didn't think it was good, but I'm telling you, it's awe-SOME!"

Dead silence.

"It comes in this big-little fuckin' rock! It gets you higher than high. You get stoner than stoned! You get stoned on top of stoned!"

"So, you like crack?" asked Rumblejunk.

"Here's how you do crack: you do two lines of the best Colombian, then you smoke the crack. I've never met anyone who never smoked crack!"

"What's it like?" asked Galapagos.

"It's like five shots of Jack and five Vicodins!"

A train whistle blew in the distance, through the trees. Michigan "yee-haw'ed" back.

A local girl passed by the Pavilion, walking a dog. Michigan's "yee-haws" turned into donkey "hee-haws."

"I wish I was that dog! I'd be getting a BONE! HEE-HAWW HEE-HAWW!"

All of the other hikers got up and quietly walked out of the Pavilion, one by one. They whispered to each other that they're going to dinner at the Port Clinton Hotel. Galapagos stayed behind to watch the packs. Michigan asked where everyone was going.

"Out," someone said curtly. The group of hikers was already 50 yards down the road.

I said goodnight to Galapagos, got into the Falcon and drove home.

July 19: My day with Spicoli

Spicoli gave me the longest interview among my time with the thru-hikers. His trail-goal was to gain a sense of self and break-out of what he felt was the crushing malaise and "sameness" of small-town Tennessee life.

Spicoli had the build of a varsity gymnast with prominent biceps and traps, as if he hoists himself up on the rings daily. He carried the heaviest pack of all the hikers I met. Fifty pounds.

"The more weight you carry, the stronger you get!" he said with all sincerity.

We sat for lunch at Cabela's in-store cafeteria, a fetishistic tableau to mythic American masculinity with taxidermied animals and a bush plane suspended from the ceiling. Our lunch: pulled pork and reuben-like sandwiches, a meatfest.

"I've been off the trail for a few days," Spicoli said, "I went to Montage Mountain for the—"

"Oh yeah! The ski area!" I interrupted.

"...Yeah...yeah, there were lifts. Anyway, there was a trap music festival going on and that whole-side trip from the AT was just a part of my whole self-discovery thing I have going on with the AT. Ever do acid?"

"LSD? No...I mean, if the right situation same along...maybe."

"LSD is love. I'm serious. It takes 40 minutes to kick in. Colors get brighter, and the bands all had lasers going. You feel love...pure...it's a social drug more than people give it credit for. I had a full conversation with myself out loud and figured out my life. It was...yeah...the most important moment of my life.

"What did you figure out about yourself?" I asked.

Spicoli thought for a beat. "I am doing the AT because one day, back home, I lost myself. I was 19 years old last year, huh, it felt longer, but anyway, I had a crisis after graduating high school... I suddenly lost me. I couldn't relate to people—a bad funk. I didn't talk to friends, or really anyone from June 2015 to March 2016. I got accepted to Colorado Mountain College at Breckenridge to study education... and I freaked out about it. I... couldn't speak, I was so depressed. Talking was too much."

"The act of speaking, forming words, was hard?"

"Yeah."

"Did you go to Breckenridge?"

"No, I stayed home and took some classes at a community college. Friends from high school saw me and wondered what happened because they thought I left, but I was just staying at home and not talking to anyone. My parents took me to a psychologist to get me help."

"What happened there?"

"I found out about the Appalachian Trail and how it changes you. I've never been happier! Doing the AT is the best thing I ever did. I'm ready to be a teacher when I finish."

Spicoli and I finished and walk out to the Vagabond Falcon. "Where do you want to be dropped off?" I ask.

"Can you go to the Eckville shelter? Is that OK?" he asks.

"Sure thing."

Vagabon Falcon is a car that may kill you, just as the Appalachian Trail is a path that may kill you. Watch the rocks. Watch other drivers. Count on bears being dicks. Count on other drivers being dumb. Count on hiker trash being drunk. Count on wayward drivers being drunk. Accept charity but don't expect it. Accept a functioning engine but don't expect it. No safety either way.

The Eckville shelter and trail head is high on Hawk Mountain and I opened all four carburetor barrels to climb the mountain road at speed. Spicoli stuck his arm out the window. No seat belts in the Falcon.

Mr. Regular is one half of Regular Car Reviews. He occasionally writes for Jalopnik, Road & Track and other places.