The Man Who Turned Speedboats Full Of Weed Into Indy 500 Glory

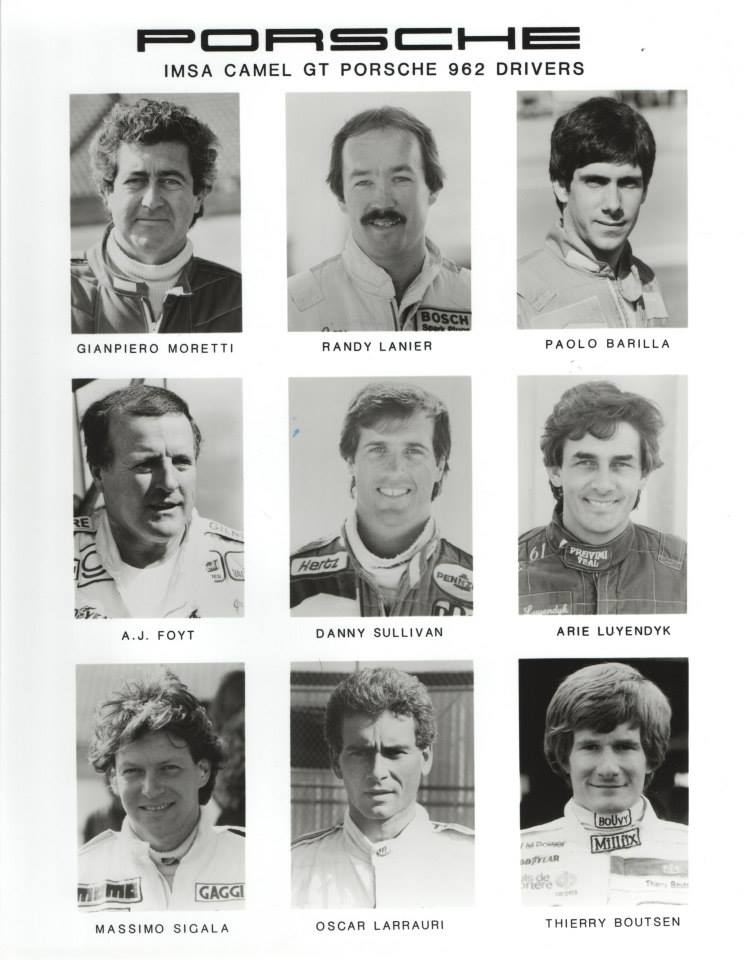

In 1986, everyone knew Randy Lanier was fast. He'd just won a sportscar championship and shattered an Andretti record to become the Indy 500 rookie of the year. What most people didn't know is he paid for his racing dreams by smuggling massive quantities of marijuana past the feds.

By 1988, Lanier was a fugitive in the Caribbean, running from the government and from responsibility for his role in a $300 million drug smuggling operation. Before long he would be caught and sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole.

At the height of the Reagan-era War on Drugs, federal prosecutors charged Lanier and his associates with shipping more than 600,000 pounds of marijuana into the U.S. from Colombia. For eight months, he was also a fugitive, hiding out until his capture in Antigua and arrest upon arriving in Puerto Rico.

Lanier's harsh sentence was made possible by a recently-passed "anti-kingpin" drug law, and the sheer quantity of drugs his operation brought to America.

During his sentencing a federal judge said the former racing star "ruined a lot of lives in this country." But Lanier, who was 34 at the time, balked at the outcome and said, "A person should not have to spend the rest of his life in prison for marijuana."

Until this month, it almost seemed like he would.

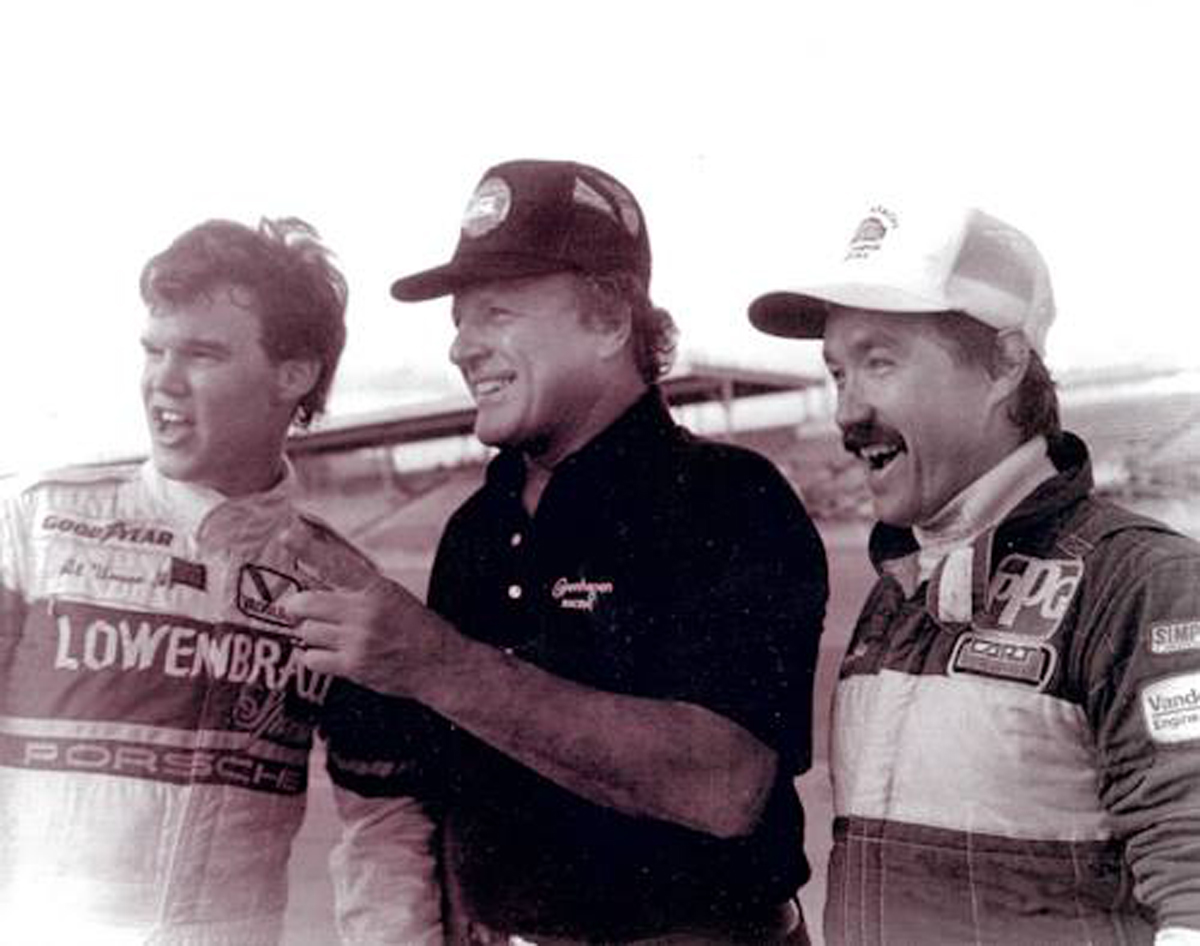

Lanier at right with Al Unser, Jr. and AJ Foyt.

Today, Lanier is a free man. Released on Oct. 15 under circumstances that remain sealed by a court order, he is living in a halfway house in Florida. He is reunited with his family. And as he looks at a world that has changed considerably in three decades, he says he does so with a new perspective.

"Everything has been going wonderfully," Lanier, now 60, told Jalopnik. "It's like falling in love all over again."

Lanier's life has been one of extreme ups and downs. Once a racing champion, Lanier was convicted as one of the country's biggest drug kingpins in the 1980s. It was a shocking outcome for driver who had raced in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, secured the top sports car racing title in America, and looked to have a bright future in the open-wheel Championship Auto Racing Teams series during its heyday.

As strange as Lanier's fall from grace was, it was largely forgotten in the racing world until Autoweek broke the news that Lanier's release was imminent.

"He's a real-life person who has just been warehoused away for years," Cheri Sicard, a cannabis activist who became acquainted with Lanier about a year ago and now runs his website and Facebook page, told Jalopnik. "The world just kind of forgot about him."

A Cinderella Story

"Racing is in my blood," Lanier said. A native of Virginia who grew up in South Florida, he recalls having always been into cars and listening to the Indianapolis 500 on the radio.

Lanier speaks in a gregarious, easy-going manner. His voice is high-pitched and full of an exuberance that makes him sound younger than he really is. And he readily admits that he's made mistakes in life, mistakes he has remorse for; things he wishes he had done very differently.

His racing career had humble beginnings, he said. At a car show in the late 1970s, he went up to a Sports Car Club of America booth and decided to sign up for a racing course with the goal of getting a competition license. Soon he was running a Porsche 356 in regional events.

He said the camaraderie of the sport — more of a team sport than many realize — was what he loved most.

"It's a wonderful individual feeling, but winning as part of a team because you went out and did your job is even better," he said.

According to the Indy Car Advocate, Lanier said his big break came in 1982 at the 24 Hours of Daytona when a crew member for the famed Ferrari-slinging North American Racing Team offered him a slot when one driver, who turned out to be Janet Guthrie, fell ill. Though their race ended in transmission failure, Lanier was invited to race in the vaunted 24 Hours of Le Mans with the team.

"That in and of itself was amazing," Lanier said of Le Mans. "Before I even got to the track, I was overwhelmed at the bigness of it."

The 1983 Le Mans race ended in retirement, but Lanier had impressive showings in other sports car races around the time, including a second place finish at the 1983 24 Hours of Daytona.

"I told my wife then that this was what I wanted to do the rest of my life," he said.

In 1984, Blue Thunder Racing appeared seemingly out of thin air. Despite having no major corporate sponsors, Lanier founded his own racing team with Fort Lauderdale brothers Bill and Dale Whittington.

Bill Whittington and another of his brothers would eventually meet the same fate as Lanier: prison for marijuana smuggling.

But in the mid-1980s, they were part of Lanier's upstart International Motor Sports Association GTP team, which won race after race at places like Watkins Glen, Laguna Seca and more.

They earned enough points to be the IMSA champions for 1984, earning the top sports car racing title in the country.

Still, more than a few other racers and league officials wondered this: Who was bankrolling this team? At no point in history has motorsports been a cheap and accessible venture; sponsorless Blue Thunder's money had to be coming from somewhere. How were they able to afford the $750,000 it cost to run in the series for a year?

Lanier would claim in interviews that a fabrication shop in Florida and a watersports rental company in Hollywood was his source of income. The world would later learn his money came from a very different place.

By 1985, Lanier was trying to transition his career into open wheel series like CART, a higher and more prestigious level of motorsports competition than he had previously been involved with. He secured a spot as a driver for Arciero Racing's open wheel team.

Lanier attempted to qualify for the Indy 500 in 1985 only to have the United States Auto Club officials decide that he didn't have enough experience racing on an oval track to be doing Indy. That, as the South Florida Sun Sentinel wrote at the time, was a race where "all a sportscar championship and a quarter will get you is a cup of methanol."

"I wanted to win the Indianapolis 500," Lanier said. "That was the goal. The competition that goes into the Indy 500 is like nothing else in the world."

So Lanier came back the next year, and became the fastest rookie qualifier in Indianapolis 500 history up to that point with a run of 209.964 mph.

His run obliterated a rookie qualifying record previously held by Michael Andretti. It was good enough to earn him a starting position in the fifth row of the race, where he ultimately finished ninth.

Today he looks back on that memory fondly. "The team was elated," he said.

But 1986 was a year that would not end well for the rising star.

The Sword Comes Down

The same year Lanier was named Rookie of the Year at the Indy 500, Bill Whittington and his brother Don Whittington were indicted in federal court on charges of conspiracy to import marijuana, tax fraud and income tax evasion. (Dale Whittington was not implicated in that case.)

According to a Sun Sentinel article at the time, the brothers were accused of running an operation that smuggled massive quantities of marijuana into the U.S., something that netted them as much as $73 million a year.

And as one does when one has millions of dollars in ill-gotten drug gains, they hid this information from the IRS.

The drug smuggling, prosecutors said, was how the Whittingtons financed their racing, including a $200,000 Porsche 935 Turbo they used to compete in the 1979 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The Whittingtons had been dogged for years by rumors that they and their associates financed their racing through drugs. From a 1986 Sun Sentinel story on the charges:

A second association with drug smuggling surfaced later that year when it was disclosed that the cars Bill and Don Whittington drove in their inaugural appearance at Indianapolis in 1980 were sponsored by C.W. Cobb, a Fort Lauderdale suntan lotion distributor who was later convicted of running a $300 million pot smuggling ring uncovered during a federal probe dubbed "Operation Sunburn."

Again, the Whittingtons denied any connection to drugs or smuggling.

"If we've been in Florida that long and been dealing in drugs, how is it we're not in jail yet?" Bill Whittington said in May 1983.

Eventually, that's where they ended up. The Whittingtons pled guilty and were sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Journalists at the time wondered whether motorsports had a "drug problem," not so much with drug use among drivers but with drug money financing racing teams. In the freewheeling drug culture of the 1980s — which coincided with law enforcement's large-scale crackdown of narcotics use and distribution at all levels — it certainly seemed plausible.

For his part, Lanier denied any knowledge of his former teammates' activities. From an interview in that same Sun Sentinel story in March 1986:

Davie's Randy Lanier is also in an awkward position, having teamed with Bill Whittington to win the 1984 IMSA championship. But even during their association, Lanier said, "I didn't even know Bill was in trouble."

"We heard rumors for years," Lanier, 31, said. "It's unfortunate, but I don't think less of him as a person.

"I hope people will take me on my driving skills, not whom I associate with."

Although federal authorities said Bill Whittington ran a $73 million marijuana smuggling operation, Lanier said he knew of no drug money being invested in Blue Thunder Racing's operation when they won the title, "not to my knowledge. If it was, I didn't see it."

Eight moths later, the drug charges came down for Lanier as well.

‘It Seemed Easy And It Was’

The thing is, Lanier had been at the drug smuggling game for a long time.

He said that way back in 1973 or 1974, he bought a Magnum power boat and through an associate got involved in unloading other boats that came into Florida carrying large quantities of marijuana.

"I kind of bit right into it, as long as I could get a portion and sell it," he said.

The Bahamas are just a short boat ride from Fort Lauderdale, and so Lanier would take his boat there, acquire as much as 700 pounds of marijuana, and then bring it back and sell it. "It seemed easy and it was," he said.

Pretty soon, the boats got bigger and bigger, as did the quantities of marijuana. "It just kept evolving," he said.

This, as he has long since admitted, was how he had paid for his motorsports ventures.

"Truth is important to me in my life," he said. "I financed racing through drug smuggling."

In October 1986, 11 people were charged in a Miami federal court by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration for engaging in what investigators said was "a major drug and money laundering organization."

The indictments centered around three people: Lanier, champion power boat racer Benjamin Barry Kramer, and Benjamin Kramer's father, Jack Kramer. (Coincidentally, Jack Kramer was related by marriage to famed mob accountant Meyer Lansky.)

The group was accused of bringing more than 100,000 pounds of marijuana into South Florida between September 1983 and June 1985, according to news reports at the time.

"That was a blow," Lanier said. "I tried to work it out with my lawyers and the Justice Department, but we couldn't come to terms."

According to FBI agents, the operation worked in three parts: Benjamin Kramer, the ringleader, arranged for the purchase of marijuana in Colombia; another party brought it to the U.S. via the barges; and Lanier worked with a network of distributors to sell the drugs.

Lanier surrendered to authorities when the indictment came down, still recovering from a fractured right leg from a crash at the Michigan 500. He posted bond and was released.

But his legal problems were just beginning. Though he was already charged with smuggling drugs into South Florida, the FBI brought down additional charges in January 1987 that accused Lanier of being part of an organization that smuggled 150 tons of marijuana in various amounts into U.S. ports in over a three-year period, according to a Miami Herald story at the time.

Federal investigators said they had netted one of the largest drug smuggling and distribution operations in America, and an up-and-coming racer in Florida was somehow at the heart of it all.

The Operation

The drug operation Lanier was charged in, prosecutors alleged, was hardly a trivial one where a small amount of foreign-sourced pot was sold to teenagers and casual smokers. It involved more than 150 people, money laundered through international banks, and distributing huge quantities of pot across the U.S. after it had been shipped from South America.

FBI officials at the time said the group had access to tugboats and barges, which were loaded up with marijuana and then secretly sailed to the U.S. (It's not clear how the pot-laden boats escaped Customs investigations.) The boats entered ports in New York, New Orleans and San Francisco.

From there, the marijuana was transferred in giant bales to trucks that took them to storage warehouses across the country. It was then sold in several states including Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Florida, California, West Virginia and Louisiana.

In total, Lanier and others were charged with brining some 600,000 pounds of marijuana into the country.

The drugs were only one component of the government's case; the money laundering was the other. Prosecutors said the ring set up numerous fictitious corporations for the purpose of laundering money in foreign banks. (One of them, a DEA agent told the Miami Herald in 1986, was called G. Reedy Holding Co., which stood for "greedy.)

DEA officials said the group laundered the drug money through banks in England, Panama, Hong Kong, the British Virgin Islands and other places, which got Scotland Yard involved in the investigation as well.

Lanier was charged by a federal court in Southern Illinois because the investigation into the syndicate "mushroomed" after a State Trooper there stumbled onto a broken-down truck delivering a small amount of marijuana. From there, authorities unraveled the entire organization.

When that second indictment came down, Lanier faced a minimum of 10 years in prison and a maximum of life in prison, had he showed up in court to answer the charges. He didn't, instead leaving his two young children behind to escape the law.

"I did probably the worst thing I could have done — I fled the country," Lanier said.

Fugitive

Despite being on the run in Europe and the Caribbean, Lanier said he never gave up his dream of racing. As unrealistic as it sounds now, he hoped to go to New Zealand and race down there.

"That wasn't reality," he now admits. He treated the potential that he would be caught and extradited like a racer would, putting it out of his mind.

"You don't think about hitting a wall at 200 miles an hour," he said. "You say, 'It's not going to happen to me.'"

Meanwhile, racing began to feel the sting from the indictments of Lanier, the Whittingtons, and other drivers involved in drug smuggling like John Paul Sr. and Jr. Drug testing became mandatory before the Indianapolis 500, and drivers from both CART and NASCAR got involved in various "Say No to Drugs" youth campaigns. For a while, IMSA was even derided as the "International Marijuana Smugglers Association."

Others faced embarrassment from even a casual association with Lanier. In another Sun-Sentinel story from 1987, famed driver A.J. Foyt recounted an incident from before Lanier fled from justice:

When A.J. Foyt was photographed standing next to Davie's Randy Lanier while leaving an Indianapolis hotel in May, he thought little of the picture that was about to be circulated by the national wire services.

Then he learned about the drug trafficking charges about to be filed against Lanier.

When the two met again in November at the Indy-car race in Miami, Foyt says he told Lanier, "Man, don't you ever walk beside me when they're taking pictures."

The FBI worked with local authorities in the countries where Lanier was suspected of hiding out. Eventually the law caught up with him in Antigua.

Lanier said he was out on his boat that day when he saw a huge boat blocking his entrance to the port. Knowing what was coming, he escaped to shore on a smaller boat, ran onto land, and was chased by several Jeeps down a down dirt road until he was captured.

Police in Antigua put him on a plane as an undesired alien, but that plane was diverted to Puerto Rico. Once on U.S. soil, Lanier was arrested.

Kingpin On Trial

As Lanier sat in jail awaiting his court case, the world moved on. Dominic Dobson beat his Indy 500 qualifying speed record. The former star's racing career became a distant memory, eclipsed by the reputation he had gained as a drug kingpin and the possibility that he could spend the rest of his life behind bars — a brutal sentence for a man who was only in his early 30s at the time.

Lanier's trial began in July 1988, along with Benjamin Kramer and other co-defendants in the case.

Witnesses — often those involved in the smuggling operation who made deals with prosecutors — testified they saw Lanier hand a power boat captain $100,000 in an envelope for bringing bales of marijuana to Melbourne, Florida; described how cash collected from drug sales flowed to Lanier and others; and detailed various aspects of how the ring operated.

Lanier's defense attorney told jurors that Lanier "succumbed to the irresistible lure of marijuana" when growing up in South Florida in the 1970s when it was a fixture of beach culture. But he maintained Lanier, who appeared tearful in front of jurors, was not guilty of spearheading a smuggling operation.

"Proof will show the federal government has entered into an unholy alliance with a bunch of dope smugglers which encouraged them to minimize their roles," the attorney was quoted as saying in UPI dispatch from the trial.

At the end of the unprecedentedly-long three-month trial, jurors didn't buy it. Lanier was convicted of engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, conspiracy to distribute more than 1,000 pounds of marijuana, and income tax fraud. The other co-defendants, including Kramer, were also convicted.

A few days before Christmas 1988, Lanier received the punishment he feared most: life in prison without parole. Prosecutors had urged this sentence, arguing it would "send a message" to men and women who made themselves wealthy in the drug trade as Lanier had. In addition, Kramer and co-defendant Eugene A. Fischer all received the same life sentence.

The reason Lanier received such a harsh sentence for the importation of marijuana was the 1984 "super drug kingpin" provision of the Continuing Criminal Enterprise Statute, which mandates life without parole depending on the amount of drugs and money involved. Lanier's operation made so much money and brought so much marijuana into the country that the law mandated he spend the rest of his life in prison.

While Lanier has accepted much of what happened to him, he still finds the sentence ludicrous today.

"I was willing to do 10 years," Lanier said. "No way should people be imprisoned for life without parole for marijuana. It's Draconian sentencing. Where's the rationality in that?"

A decade in prison would have been "a sane amount to keep me from doing it again," he said. "If your freedom is taken away, and you don't learn something from that, you don't understand what freedom means in the first place."

The Aftermath

As Lanier languished in prison, his family members also felt the sting from his crimes. His girlfriend, Maria De La Luz Maggi-Lanier, was sentenced to nine years in prison in 1993 for money laundering. She later became his second wife while he was behind bars. Federal agents confiscated his brother's home in 1991 and auctioned it off, saying it was used for illegal activities, although the brother was never charged with any crimes.

Lanier attempted several appeals while in prison, including alleging that one of the prosecution's witnesses lied under oath, but none were successful. Meanwhile, federal agents cashed in on the organization's assets — cell phones, Corvettes, boats, jewelry and real estate were all sold off to line the government's pockets. According to one St. Louis Post-Dispatch story, Lanier's seized assets alone totaled $150 million.

As for his co-defendant Benjamin Barry Kramer, life behind bars got even stranger. In 1990, one of Kramer's associates arranged an escape attempt where a helicopter would fly into the exercise yard of the Dade's Metropolitan Correctional Center where he was serving time and pick him up.

Not surprisingly, the plan didn't work. As Kramer held onto the runners of the helicopter, its rear rotor became entangled in a fence, causing the machine to come crashing down into the yard. Kramer suffered a broken leg in the incident.

"Desperate men do desperate things," Lanier surmised about his former partner. "He didn't want to spend the rest of his life in prison. But who does?"

Another case that dogged Kramer for years was his link to the murder of Donald Aronow, owner of a marina near his and the inventor of the "go-fast boat." Aronow was shot to death in February 1987. For years after that his former protege Kramer would be one of the prime suspects, but he wasn't charged. (Lanier was not involved in that case.)

Kramer's lawyers long denied their client was involved in Aronow's murder. But in 1996, Kramer — already serving life in prison for drugs — pled guilty to manslaughter charges and copped to ordering Aronow's death over a business dispute. Kramer took the plea as part of a deal to get transferred from county jail, where his health was suffering, the Miami Herald reported at the time.

Kramer remains in prison at a high security federal facility in Florida.

Freedom

As for why Lanier was released so suddenly, that remains perhaps the greatest mystery of this entire case.

With the motion sealed by a federal judge, prosecutors and defense attorneys are unable to talk about why exactly Lanier has been let out now, almost 30 years after his conviction.

Sicard — the cannabis activist who befriended Lanier while he was behind bars — called Lanier "Mr. Sunshine," and said he never gave up hope that he would be released. "He's the most positive person I've ever known," she said.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Jim Porter, who prosecuted the case, said he couldn't elaborate on the circumstances behind Lanier's release because of the seal. However, he said such outcomes do happen from time to time.

Porter added that the U.S. Department of Justice's stance on such crimes has evolved since the days when Lanier was sent to prison. Some of the recent "Smart on Crime" reforms pushed by Attorney General Eric Holder included avoiding life imprisonment sentences solely based on the quantity of drugs, Porter said.

And while Lanier was not a part of the program, the U.S. Sentencing Commission has begun reviewing and possibly shortening the sentences of tens of thousands of drug offenders in an effort to de-crowd prisons.

"In the future, this will not be a completely unusual situation," Porter said.

Lanier dips his toes in the ocean following his Oct. 15 release

Lanier said that while in prison, he took up yoga, tai chi, meditation, painting and chess. He mentored younger prisoners. He read car magazines, and now marvels at seeing some of them on the streets. He stayed close with his two children, now 28 and 35.

"I don't have an ounce of bitterness in me at all," Lanier said. "I know who I am. I have an understanding of my inner self."

Few people find thrills greater than 200 mph race cars. Lanier thinks he paid the price for his.

Lanier said he's good with the conditions of his release, which mandate drug and alcohol counseling and time in the halfway house. He hopes to re-enter society soon. He's 60, but said he feels 30, and he hopes to find a job working around cars or in racing if he can. He's wowed by the Internet and cringes at how everyone seems to have their nose stuck in a cell phone all the time.

He wants to get back to a track soon. He wants to smell the gas and the rubber and the asphalt.

"One moment at a time," he said. "I'm gonna toe the line 100 percent and make the best of it. I look forward to every moment of every day."