The Dream Of New York's Forgotten Elevated Subway

Until 1969, you could go to the Myrtle Avenue-Broadway station in Brooklyn, walk upstairs, and go back in time, to a borderline-decrepit wooden platform served by an ancient wooden train car (the last ones in the system), and there you could continue your journey west on the Myrtle Avenue Elevated.

"They had this seating made out of cane reeding, it was woven and it used to be all messed up. If you had dungarees on it wasn't a problem, but if you had dress pants on it would poke holes in your clothes, and women, it would catch on the skirts," said Michael McKay, a retired projectionist living in Ridgewood with memories of the line.

He added that a breeze often came from the large, open windows, presenting you with the unique smell of each neighborhood's industry, such as Rheingold beer and the chemical, steamy smell of knitting mills.

It was an experience out of another century, but for the 4.1 million commutes it facilitated per year at the time of its closing, it was "old reliable." As one rider told a New York Times reporter, "it looks like a Toonerville Trolley, but it gets there on time."

For sure, 1969 saw America, and its methods of moving people around, at a crossroads. The U.S. had just landed two astronauts on the moon, and human (particularly American) ambitions for where we could go soared to new heights. But for us non-astronauts, an era of disinvestment in public transit was well underway. After decades of innovation and growth, many transit networks across the country were shrinking.

And in Brooklyn, 1969 marked the last year (October the last month, and the fourth the last day) that you could take the train from North Brooklyn, a once-industrial center that is today home to gentrifying neighborhoods like Bushwick and Ridgewood, to the busiest, most populous part of the borough.

In doing away with what was then seen as an eyesore, the city didn't know what it had.

The El's ultimate destination was, and still is, the borough's civic center. Look west down Myrtle Ave today from Broadway and you'll still see a block-long steel skeleton reaching out towards it. Downtown Brooklyn is home to courthouses, museums, schools and universities, and the largest central business district in New York City outside of Manhattan. Billions of dollars have flowed in from private investment after the area got rezoned in the 2000s, and it's easy to understand why if you're a bureaucrat or a stock market type just over the water in lower Manhattan. The Fulton Mall, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Barclay's Center, and a dense concentration of the borough's colleges and universities are served by the 2, 3, 4, 5, B, D, N, Q and R trains, making it easy to get to, particularly from Manhattan as well as some neighborhoods in Brooklyn—but not others.

Further northeast on Myrtle Avenue, Williamsburg and its adjacent neighborhoods of Bushwick and the Brooklyn/Queens-straddling Ridgewood make up another, equally important Brooklyn, a birthplace of major music, fashion, food, and intellectual trends.

But it's cut off. The main connection from there to the borough's heart is the B38 bus, which the Bus Turnaround Coalition has found to have a 53 percent on-time performance rate. (They gave it an overall letter grade of "D.") Going to other neighborhoods in Brooklyn often involves riding the M or L all the way back into Manhattan, then going back into Brooklyn on a different line. North Brooklyn might as well be a different borough.

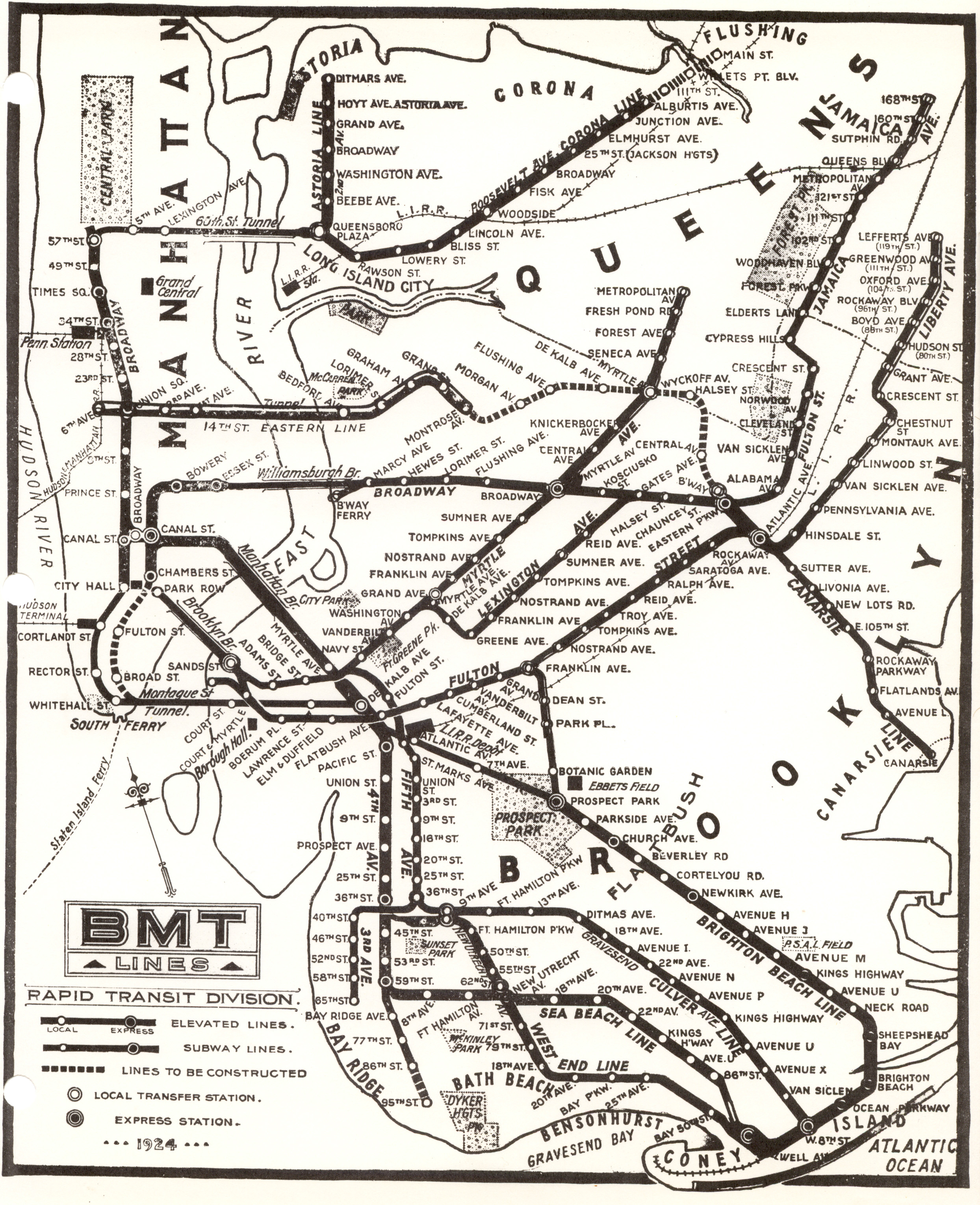

The Myrtle Avenue Elevated, which partially survives today in a modernized form as the M train, originally opened to fares on April 10, 1888. After going through Ridgewood and Bushwick, it served Bedford-Stuyvesant, Clinton Hill, Fort Greene, and Downtown Brooklyn, with stops at Sumner Avenue, Tompkins Avenue, Nostrand Avenue, Franklin Avenue, Grand Avenue, Washington Avenue, Vanderbilt Avenue and Navy Street. It played an important role in urbanizing the then-rural areas of north Brooklyn and southern Queens, and just 10 years after opening, the line was even extended across the Brooklyn Bridge, where it terminated in Manhattan's Park Row.

This heyday, however, turned out to be shorter than the time that has now passed since its closure. In 1944, the Adams Street, Sands Street, and Park Row stations were closed, cutting off the connection to Manhattan once again after 46 years of service. By the late '60s, the city had allowed the line to deteriorate. It had gotten to the point where, it told passengers, it would cost between $13 and 25 million to repair and strengthen for the modern steel subway cars. This would be about $92-176 million now, a pittance in today's MTA money.

(For photos of what life looked like on the Myrtle Ave El in the mid- to late-1950s, look to these images from photographer and Brooklyn native Patrick Cullinan, linked here but not republished for copyright reasons.)

By 1969, it was decided that the beleaguered Myrtle Avenue BMT line (as it was then called) would be pared back to the version we know today, with the remaining stations east of Myrtle-Broadway receiving the modern steel cars and the upgrades needed to carry them. "We have reached a point of no return," Harold McLaughlin, assistant general superintendent of the Transit Authority, told the Assembly Committee on Transportation. "Either money had to be made available or the line had to be discontinued."

What remains of the line today only enters Brooklyn through the Williamsburg bridge and confines itself to the northern part of the borough. Bushwick and Ridgewood were left without a direct subway connection to Clinton Hill, Fort Greene and Downtown Brooklyn.

Several "subway deserts" were created that persist to this day; in fact, to this day there is only one train station on Myrtle Avenue west of Broadway, the Myrtle-Willoughby G. Developers openly admit that they are less likely to build anything in these "deserts," freezing them in time.

Brooklyn residents were outraged by the city's decision to follow neglect with demolition. People living on the further reaches of the line in Ridgewood would be particularly affected, with a major route out of the north Brooklyn vicinity cut off. In July, Assemblymen John Flack and Assemblywoman Rosemary Gunning of Ridgewood wrote to then-MTA Chairman William Ronan, arguing that "the elimination of train service to downtown Brooklyn will create severe hardship and great inconvenience to workers, students, shoppers and other residents who must use the line daily."

On September 30, 1969, five days before the line was set to close, protestors marched in front of the New York City Transit Authority building at 370 Jay Street with signs like "Our constitutional rights have been denied us! No public hearing/Help us Save the El" and "If the El is so bad, how come it was the only one that ran after the snowstorm?"

Now, the Myrtle Avenue El wasn't Brooklyn's only elevated line linking neighborhood to neighborhood. (Manhattan had yet more, but those are a story for another time.) You can still ride the Franklin Avenue Shuttle today along its four stops connecting Flatbush to Crown Heights and the bottom of Bed-Stuy, even though the reason the line was originally constructed is no more. (The line was built to take people to the long-gone Ebbetts Field, home of the equally-gone Brooklyn Dodgers.)

The Franklin Avenue El had a similar history of neglect and then planned demolition, only it was saved by a tide of community action and revival in the 1990s. Locals forming action groups and committees pointed out that other neighborhoods with newer subways got their lines repaired, as the New York Times reported, while the Franklin Avenue line was met with austerity. That campaign worked, but in the 1960s, the city wasn't having any of it and tore down Myrtle no matter how much the locals called it out as a mistake.

Residents along the line continued to protest after it closed, showing up to a State Transportation Committee hearing that January to plead for the line's restoration. The New York Times reported that "Some witnesses arrived at the hearing an hour and a half late because of a subway delay on the small, northernmost spur where trains still operate on the line. A few persons were still shivering from the chilly walk they had taken from their stalled train to the nearest station." Students in southern Queens attending colleges in Brooklyn had been forced to transfer to buses to complete their journeys, which even back in 1970 "cre[pt] between parked cars on Myrtle Avenue and t[ook] twice as long as the El did." Even in the era before today's miserable gridlock, it was clear within a few months that Myrtle Avenue El riders had gotten a raw deal. It was just another blow to the affected neighborhoods during a lengthy period of white flight, disinvestment and decline, culminating perhaps in the looting and arson during and after the 1977 New York City blackout.

But not everyone at the time could see the elevated train as a public good serving residents and connecting neighborhoods. Its deteriorating wooden structures were regarded by various interests as an outdated blight, and removing them was often talked about as an aesthetic improvement, opening the streets beneath them to light and air. Local neighborhood groups such as U-CARE (University-Clinton Hill Area Renewal Effort) lobbied for the demolition of the Myrtle Avenue El, citing the increased real estate values and tax benefits to the city that had occurred when similar structures were demolished in Manhattan.

But these benefits were abstract in comparison to riders' everyday needs. As constituents decried the line's closure at a State Transportation Committee hearing, a Brooklyn merchant retorted that "community planning boards held a hearing in the Brooklyn Borough President's office at which members of the community expressed approval of these plans." Clearly, the other people at the hearing had not been included. (A 1973 New York Times article pointed out that the demolition of the structures alone wasn't exactly a stimulus package: "Recently the oldest portion of the Myrtle Avenue elevated... was taken out of service and most of it dismantled, exposing to the sunlight the drabness and poverty that had characterized long stretches of Myrtle Avenue.")

Now, with transit construction costs in New York beyond the realm of sanity, the demolished elevated lines make us wonder about what could have been.

They also point to an era when transit was a public good, an ethic that New York has never completely abandoned, and that it is holding up once again as an example for other cities to follow. Turning back to Els could even help solve the MTA's exorbitant cost problem, which has prevented it from expanding significantly for over 70 years. Modern elevated tracks are made from concrete, making them whisper-quiet, and can be elevated high enough to free up the streets below to light and air.

With startups and entrepreneurs pushing their algorithmic ridesharing systems along these routes and dreaming up boondoggles like the BQX, it's important to remember that not only is better transit possible, but that it once actually existed.