The 'Crime Of The 20th Century' Was Made Possible Thanks To A New Invention: The Rental Car

100 years ago today, Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold murdered Bobby Franks in a rental car.

Roaring '20s Chicago was the epicenter of a wave of American inventions, like a new, more violent kind of organized crime and most importantly in this story, the rental car. One hundred years ago today, the humble rental car was the lynchpin in a plan by two rich teenage psychopaths to commit the perfect crime; the senseless murder of a 14-year-old boy.

Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold were two friends, sometimes lovers, who came from the upper crust of Chicago. Both seemed to have every advantage in life. A year before the murder, the outgoing and friendly Loeb graduated the University of Michigan at 18 years old—the youngest person ever to graduate from the university at the time. The more reserved, severe Leopold was obsessed with the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of the superior man. He was still attending the University of Chicago as a law student at 19 years old. Sure, their upbringings were a little screwed up, but they never wanted for anything. Indeed, both would have simply inherited positions of power and respect without lifting a finger, if they hadn't committed a horrifying murder.

They believed so much in Nietzsche's Übermensch because, clearly, the philosopher was talking about guys just like them. To prove their superiority, they started small. The two engaged in petty acts of crime like thefts and vandalism, but it wasn't enough. The pair believed they were intellectually superior to their fellow human beings, and to prove it, they'd commit the perfect murder just for the thrill of escaping the consequences.

They spent seven months planning the crime. One of the most complicated aspects was renting a vehicle for the murder. Loeb's own Willys-Knight was flashy—bright red, covered in chrome and sure to be recognized by any potential witnesses. To get away with the perfect crime, the two would-be murders needed the perfect getaway vehicle. So they turned to the brand new industry of rental cars, born right there in their hometown of Chicago.

A story originally published in 1952 in the Saturday Evening Post details what the early days of rental cars was like:

In 1920, however, Walter L. Jacobs, a Chicago car salesman, embarked with a stock of 12 secondhand Model Ts on what was to be the nucleus of the present Hertz system, first taken over by John Hertz, of Yellow Cab fame, then becoming a division of General Motors.

In 1924, a rental Willys-Knight became infamous as the car used by Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold in murdering Bobby Franks in Chicago. This luridly emphasizes the fact, which old-timers candidly admit, now that the business is unimpeachably respectable, that during this first rugged decade their patrons were not all Sunday-school superintendents.

One veteran says renters used to be 90 percent bootleggers, hoodlums — the Capone mob, for instance — and ladies practicing the world's oldest profession. The percentage may be exaggerated, but few deny the general impression. Bootleggers, for instance, liked being able to make customer deliveries in inconspicuous rented jobs with never the same license tags twice. After repeal, however, the index of customer respectability gradually rose.

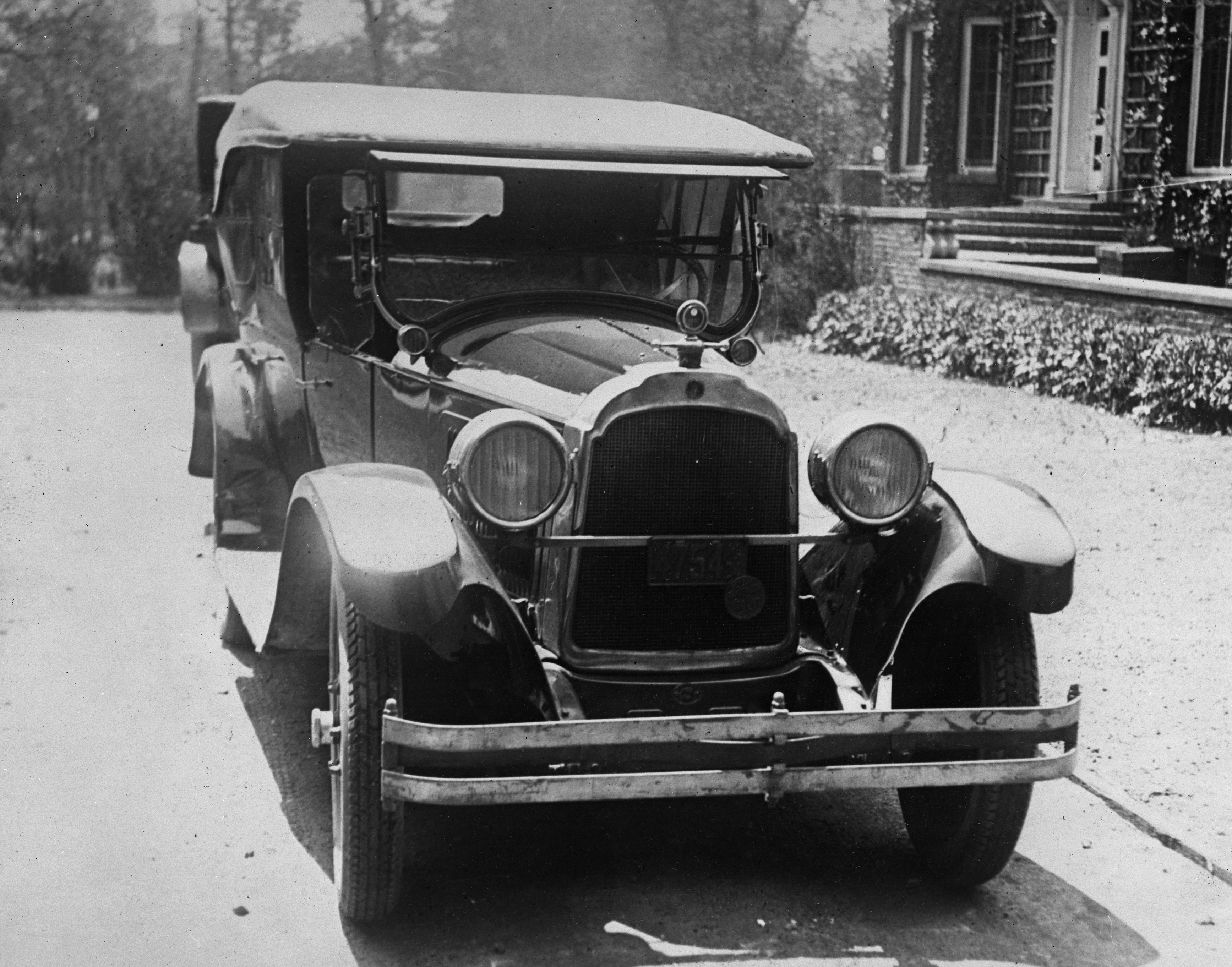

Leopold and Loeb rented a Willys-Knight which looked something like this:

Of course, it was a pain to rent cars back then, as it is today (some things never change.) Just check out the lengths these two went to, from their confession:

What kind of a car does Nathan Leopold have?""Willys-Knight sport model, red in color. His car is very conspicuous, and for that reason we deemed it inadvisable to use it, and therefore decided to get a car — rent a car from the Rent-A-Car people. Also in view of the fact that such a car, if obtained under a false name would not be incriminating, were it to be discovered in connection with the crime.""So what did you do in connection with the car?""So in order to assume a false name and a real identity, we went and Leopold deposited $100 at the Hyde Park State Bank under the name of Morton D. Ballard. from Peoria. Following out the same plan, I went down to the Morrison and registered under the name of Morton D. Ballard., carrying with me a suitcase, an old suitcase containing some books.""Where did you get the books?""From the University of Chicago Library.""And the purpose of taking those books in that suitcase to the Morrison Hotel was to lead them to believe that you really intended to live there?""Yes.""And had clothing of some kind?""Yes. We addressed several letters to the Morrison Hotel inder the name of Morton D. Ballard.""So that you might receive them?""So that we might recieve them; and on the following day I went in and got those letters.""That is, you would call for those letters on the following day?""Yes, the day after that, and I am practically certain that is what it was, it was the third day — the day after we went — pardon me, down to the Rent-A-Car people.""For the purpose of fixing the time, that was about when?""About eleven o' clock in the morning.""I mean, about the twentieth day of April?""Yes. I am not sure of the time, I mean the date. I wouldn't swear to that. The twentieth of April, how long is that?""Just about a month before.""Yes, about a month. Leopold went alone with four hundred dollars in his pocket, which I had drawn from my account in the Hyde Park State Bank, and with the letters sent to Morton D. Ballard. at the Morrison, as with also his check book — not check book, his bank book from the Hyde Park State Bank. He told the Rent-A-Car people that he was a salesman new on the route, that was the first time he had covered this district, he was a salesman from Peoria, and that the only person he knew in Chicago was a Mr. Louis Mason. He told them this, because the Rent-A-Car people demand three in-town references, in order to take out a car. However, he wanted to persuade them to give him the car, anyhow, in view of the fact that he was new, and that Mr. Louis Mason would vouch for him, and also because he would be willing to deposit $400 there if necessary in order to get the car."I was posted in a little restaurant or cigar store on Wabash Avenue. Do you want the exact name?""Yes, if you recall the address?""This cigar store is a little bit north of 16th street on the west side of Wabash Avenue. I went in this cigar store and sat near the public phone booth whose number Leopold had, and he told them this was the number of Mr. Louis Mason. The Rent-A-Car people called up, and I immediately answered the phone and told them that I was Mr. Louis Mason.""You are in this cigar store now, or in the vicinity of 16th Street, near the Rent-A-Car people?""Yes.""And you placed yourself at the booth?""Yes. The phone rang, and I immediately answered the phone and the Rent-A-Car people asked me if I was Mr. Louis Mason. I said, 'Yes.' They asked me if I knew Mr. Morton D. Ballard. of Peoria; I said 'Yes,' They asked me if he was dependable. I said 'Absolutely dependable.' That was the end of the conversation.""You were then posing as Mr. Ballard?"

"No, I was posing as Mr. Louis Mason; Leopold succeded in getting the car and told the Rent-A-Car people to forward the identification card which they demand as necessary to get a car any time without the trouble of getting references over again and everything, he asked them to forward this identification card to the Morrison Hotel. We took the car out that morning at eleven and returned it at four.

Almost not worth going through all that just to commit the pointless murder.

Once they actually got their rental, Leopold and Loeb drove around for two hours until they spotted Loeb's second cousin, Bobby Franks, a boy from a similarly wealthy family. Franks was lured into the car, bludgeoned, suffocated (most historians believe Loeb did the killing while Leopold drove, but under questioning both claimed to be the driver) and his body unceremoniously tossed on the floor in the back. The two drove around until nightfall, when they made a half-assed attempt to disfigure the corpse, leaving poor Bobby Franks naked and stuffed into a drainage pipe.

Police caught the two almost immediately. There wasn't even time for Bobby Franks' father to drop the bogus kidnapping money the two tried to squeeze out of the family before he was informed there was no longer a child to ransom. Bobby Franks' body was found by a passerby, and found alongside the body was a custom pair of eyeglasses that had only been made for three people in the world; one being Nathan Leopold. Once again, the car came into play, from the Washington Post:

Leopold gave police a flimsy alibi that he and Loeb had been driving around Chicago in his family car the night of the killing and picked up two girls whose last names he didn't know. The Leopold family's chauffeur, however, told police the family car hadn't left the garage that night. Plus, Leopold's handwriting matched that on the ransom letter envelope, and the typewriter used for the note matched one Leopold used for legal notes.

With evidence mounting, Leopold and Loeb separately confessed. However, each claimed to be the driver and said the other was the killer. The slaying was so shocking that newspapers declared it the "crime of the century" — with 76 years still to spare in the 1900s.

After they were caught, the two showed no signs of contrition. In fact, they said given the opportunity they would kill again. The two pled guilty and their lawyer—the famous attorney Clarence Darrow—argued for 12 hours in front of a judge that the pair did not deserve the death penalty. He was persuasive, and both received 99 year sentences. Loeb died in a fight with an inmate in 1936 while Leopold actually got a second chance at freedom. He was paroled and lived for 13 years in Puerto Rico before his death in 1971.