The Convoluted History Of Why The Carrera GT Sounds Like An F1 Car

How an engine intended for racing at the highest level found a home in a storied automaker's vanity project.

The Porsche Carrera GT has always been known for its screaming wail of an exhaust note, not so different from an old F1 car. As it turns out, there's a very good (if complicated) reason for that.

Let me start by saying Porsche has a long and often-overlooked history as an F1 engine manufacturer. The company powered two constructor's championships and three driver's championships in the '80s with over two dozen wins to their name.

Well, not exactly to their name.

Porsche designed and built the V6 turbo engines that took McLaren to its very lofty highs from '84 to '87, but you tend not to hear about that. The reason is because the entire engine project was funded by a Luxembourger company of the name TAG (Techniques d'Avant Garde), and they held the naming rights to the engines. Some press reports credited Porsche, which had their name stamped on the plenum chamber, but the German company's great success still hasn't had the recognition it deserves.

Porsche's Grand Prix program stretches even further back in the 1950s and '60s, actually. They started out racing two-seaters in Formula 2, then built a dedicated single seater F2 car, and then in 1961 finished the design of a fully-fledged F1 car, the 804. It had a mid-mounted air-cooled flat eight and it managed to score a single win with American Dan Gurney at the wheel in 1962's French Grand Prix at Rouen.

Don't forget to tell your friends about that win at parties. Rouen! You'll remember it forever.

In any case, after Porsche's turbo success with McLaren in the '80s, they tried a naturally aspirated engine in the '90s. The same guy who was in charge of the '80s V6 turbo program (the great Motor Pope Hans Mezger) was at the head of the '90s N/A one, and his solution was basically to graft two of those old V6s together and drop the turbos.

Here's Mezger standing proud with his new V12. It took its power out of the middle of the engine (a Mezger specialty) and its twin-six origin is pretty clear.

It was one of his rare failures.

The engine was overweight and underpowered, possibly because of confusion between Porsche and their F1 customers, the much-maligned Footwork team. Porsche's 3.5 liter V12 was actually so large that Footwork had to redesign their car just to get it to fit.

The 1991 Footwork with its Porsche V12 was so bad that Footwork actually dumped Porsche and switched to Ford engines in the middle of the season. To say that the program didn't go great would be an understatement.

In the midst of all of this, Porsche was developing a new engine for the 1992 season, a 3.5 liter V10. The Footwork deal getting cancelled basically pulled the rug out from under the new engine and Porsche had to figure out what to do with it.

Porsche officially denied the V10 program existed, as motorsport tech site Mulsanne's Corner claims.

Porsche couldn't exactly let a perfectly good race engine lie around, so it ended up powering Porsche's upcoming Le Mans program. Porsche had been very active in Le Mans in the 1990s with three overall wins. Two came from Porsche-powered TWR prototypes and one came from Porsche's prototype-in-a-fancy-suit GT1 car.

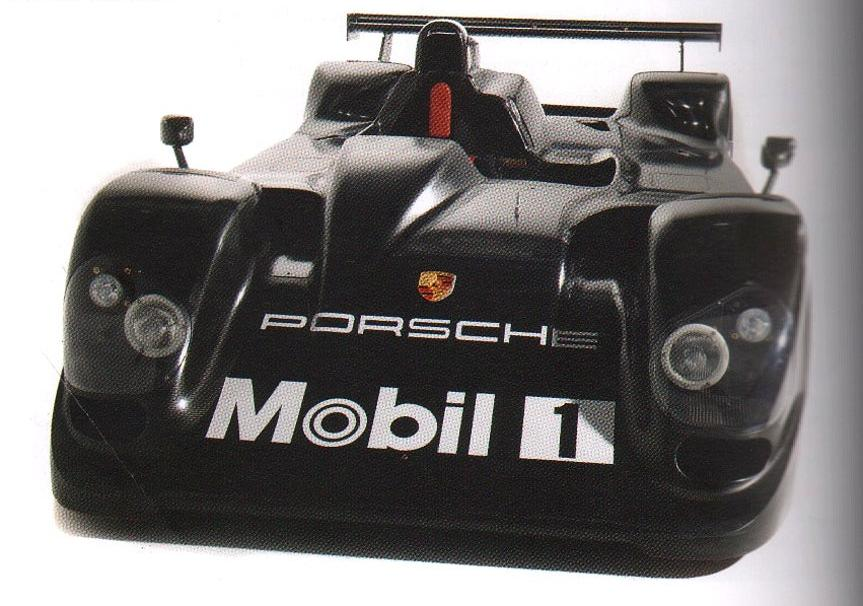

That last GT1 win was in '98, but it was clear that full-fledged open-topped prototypes were the way forward for the 24LM, so Porsche set about developing an LMP1 car. They called it the 9R3 and they did a fair bit of work to the F1 engine to make it Le Mans-viable. They increased the capacity to both 5.0 and 5.5 liters, added in air restrictors for endurance racing's regulations, and they deleted the F1 engine's cutting-edge pneumatic valve system.

This is the only studio photo of the car I've ever seen, found by Mulsanne's Corner and taken from an internal Porsche calendar.

The motorsports team got reasonably far with its development when the whole program got canned.

Porsche as a company was struggling financially and their head honchos axed the fledgling LMP1 program and dumped its funding into the Cayenne SUV as a last shot at keeping things afloat. It may be more than a coincidence that the Cayenne shares its platform with the VW Touareg and that VW's friends at Audi started to dominate Le Mans just when Porsche's program got cut. Was a nefarious deal struck between Porsche's Wendelin Wiedeking and VW's Ferdinand Piëch? That's a question for conspiracy theorists.

Much to the disgust of Porsche purists, the Cayenne was a huge success. Suddenly Porsche had enough money to greenlight an expensive vanity project, so they approved the design of a new brand-affirming supercar. I think you can see where this is going.

Porsche grabbed that old V10 off the shelf, probably gathering dust after not one but two failed racing programs. They bumped the displacement again, boring it out to 5.7 liters. It made 605 horsepower and 435 lb-ft of torque.

Like a racing engine, the Carrera GT's motor was dry-sumped and bolted right to the carbon-fiber chassis as an integral member. It's a 68-degree vee with no cylinder liners. The cylinders are coated with Nikasil, a nickel and silicon solution Porsche had been using since the 1970 917 and was most famously deployed in, uh, the Chevy Vega.

I can also tell you that the engine used a fully-closed deck for strength, titanium conrods, and variable cams. Porsche further stated in their press release that "camshaft drive is a combined sprocket/chain system with rigid cup tappets that guarantees a stiff and sturdy valve drive," though I have no idea what that means.

I can, however, say that I now feel a distinct lack of cup tappet rigidity in my vehicles.

The whole engine weighed 472 pounds.

When the Carrera GT went on sale in 2004 (four years after its debut as a concept car), its figures were low compared to its supercar rivals at Ferrari or McLaren-Mercedes, but the way the engine worked was like nothing else on the road.

There was the sound. Dear lord the sound. It's a challenge to find good videos of what the car sounds like wailing up to the 8,400 redline, and I think this review with Germany's Tim Schrick gets it best. The title of the video is "Drift Orgy in the Mountains," and you can it appreciate even if you don't speak German.

The revs rose and fell like a racing engine, and the thing wailed like the F1 car it was intended to be. Coupled with a tricky carbon clutch, the Carrera GT was actually so sensitive to the throttle that it developed a reputation for stalling. Here's how Car and Driver described it.

The downside to this is that you will stall the car from a standstill. Everyone who sat in the driver's seat did. Well, you'll either stall it, or your big dumb right foot will call for far too many revs, spin the rear tires furiously, and a second later get shut down by traction control.

People soon figured out that you had to let off the clutch with your foot completely clear of the gas pedal to get the car to trundle away. Porsche eventually figured out some kind of fix and the later cars weren't such aggressive stallers.

But little tricks like that are just what you get when you have a road car with an engine from not one, but two racing cars.