The Cautionary Tale Of An Idiot, A Mercedes C43 AMG, Bald Tires And 2,000 Miles Of Blizzard

I should have known that things were off to a bad start when the airport check-in kiosk wouldn't read my passport.

Sure, the woman behind the counter was cheerful when she told me I "mis-booked" my flight, and that I had to cough up $600 to get the flight I wanted in the first place.

But it didn't help, and it later proved to be the first of several bad omens to come.

The plan was to fly from my home in Minneapolis to pick up a car in California and drive back. I wanted to take U.S. Route 50 out of Sacramento through Lake Tahoe and continue on across Nevada, and from there I'd shoot up through Salt Lake City and across the Dakotas.

I hadn't bought something and drove it this far in some years. The last time was a 1972 911 from Virginia. Or maybe that 200,000-mile 996 from South Carolina. Or the Yugo GV from North Dakota. It all runs together.

Anyway, this time my requirements were specific. I wanted a manual, from Europe, with rear-wheel drive, it had to be special, and under $10,000. Time on Bring a Trailer proved how unexpectedly difficult this has become; evidently I missed the boat on cheap E36 M3s, and every other M3 under $10,000 has had a hard life. Interiors are destroyed, miles are high, and more often than not, there's a salvage title in the glovebox. And to be honest, they're underrated, but not that special.

What else was there? An E34? E30? E39? An older manual Mercedes 190E? A Porsche 944? I looked at everything. Facebook is useless for a buyer searching for in specific locations. Craigslist is still a crapshoot. Phone calls are frustrating. Most cars were sold, but the ads still lingered. I told one guy he was a little high on the car. He thought I meant actually "high" and hung up on me.

An imported E34 turned up, but after several days of back and forth it turned out the guy didn't have a title. Another guy with an E30 ghosted me. And thanks to that aforementioned auction website, where a six-speed 540i with a manual and 150,000 miles commands obscene prices, every slightly unique toilet of a car is forged in gold, cast in the foundry that is Bring a Trailer.

I settled on a 190E, a cool car overshadowed by "God's chariot," dead reliable when maintained right and pretty comfortable. They made tons of them, and while most are totally pounded, the good ones are still cheap at around $4,000 to $6,000. The perfect one existed on Craigslist in Ohio, but the owner I contacted was out of town for a while.

Back to square one. But that took me where this journey ultimately led: the Mercedes C43 AMG. A 4.3-liter V8 with 300 horsepower in a tiny '90s C-Class? Sign me up.

This car was a product of an era when Mercedes was kind of struggling to catch up to the stuff made by its German rivals at BMW's M division. For much of the late '80s through the late '90s, Mercedes' most badass cars were made by someone else—the AMG Hammer, or the 500E built by Porsche. By stuffing a V8 into what used to be the six-cylinder C36, Mercedes—which took full control of AMG in 1999—aimed to strike back. It was more expensive than the E36 M3, and despite having significantly more power, didn't perform quite as well in many regards.

I didn't care. It was special.

Yet just like the E36 M3s, the early AMG stuff has been badly abused. The unfortunate thing is that production numbers were far lower, so finding a good one is thus considerably tougher. Only about 4,200 C43s were manufactured from 1997 to 2000—and that's globally. The AMG badge and its cheap initial cost make it the perfect choice for sketchy guys in striped track suits whose hobbies include carrying concealed weapons and referring to everything as "lit."

The upkeep isn't easy though. Unless you do the work yourself, just changing the spark plugs (it's a twin plug engine) and wires is a $500 affair, and brakes can be over $1,000. Deferred maintenance has slid most C43s into the dustbin of history, or worse, they're somehow kept limping along, as mere husks of their former selves. I found a black one with 150,000 miles before I found out in the fine print that it was actually in Puerto Rico. Another graced Bring a Trailer, but it had a salvage title.

Just before I gave up on getting a C43, returning to beige interior, beige dash, beige emotion E39s, I came across a white one in San Francisco. After a few pleasantries and more photos, a deposit was exchanged, and a flight was booked.

On the wrong day.

Upon meeting this car it proved cleaner than I'd expected, a rare occurrence. According to the owner it needed an alignment, and according to my fingers the rear summer tires were over half worn, but not to the bars.

It drove exactly what a car made for hauling around suitcases full of track suits and MP5s should feel like. The 300 HP did its job and pressing your chest lightly into the seat. The shift at 100 feels the same as the rest. When it was new, 300 horses was a lot, and honestly, it feels like a lot in a small car like the C43. The cruise control worked just fine at 135 mph, and there was no problem getting to the electronically limited 155 if you wanted to, which I didn't.

The steering was heavy, and pushed back nicely with no electric motors interfering with the conversation. The traction control, however, was pretty annoying—there's no way to turn it off short of presumably unplugging the ABS module, so I was stuck with a triangle strobe light off the line or whenever I tried to re-enact my favorite scenes from Ronin.

I was set to meet an editor from another car publication for breakfast the next day before starting my drive back to Minnesota. Just before taking off on my connecting flight I scheduled an alignment for that morning. On the test drive, the alignment felt okay, just a slight drift to the right. Manageable.

My budget had been stomped by the $600 plane ticket. I checked the weather for the route home. It seemed like it could snow, but I figured I could drive around it.

I cancelled the appointment. A late afternoon departure put me in Nevada at 9 p.m.. I'd drive through Lake Tahoe, and take highway 50 across Nevada. It would cost me an hour on paper, but I knew I could make up time on the desolate highway in the obviously Autobahn-engineered C43. Right?

The climb up to Lake Tahoe from Sacramento started out well. It was about an hour out when I realized things were going poorly. Signs popped up warning of snow chains and impending hazardous road conditions. I'd checked the weather. How could this be happening?

The snow started to pile up imperceptibly on the side of Interstate 80. First a trace, then it was up to the armco barriers. I had to quit fiddling with my radio transmitter.

The rain had turned to flurries, and slush was starting to pile up on the road. Deep ruts from tire chains had destroyed the right lane. The alignment went from "Yeah okay, this isn't so bad, just a little pull to the right" to "Do I remember what my kids look like?"

The car darted in and out of the ruts. The front toe was way out and the rear tires were worthless. Slush between the lanes yanked the car around. The giant yellow triangle in the middle of the speedometer blinked, warning me to not do whatever it was I was doing.

I reduced my speed to 50 mph, eventually settling on 35 mph. I crept just off center in the rutted right lane as more responsible motorists with good alignments and good tires passed by.

The snow was past the armco and my roof. It towered above the car, 10 to 15 feet from the ground. It was a white wall. I wondered what crashing into it would be like.

Nevada was a welcome sight. Lower elevation and drier air cleared the roads, and in turn, my speeds increased. I realized the wiper that was on the car was at the end of its life. The local small town parts store didn't have a new one. It's a mono wiper, moving like the guy throwing the advertisement in front of the "taxes for free" office.

Walking back out of the store, I noticed that the driver's side headlight wiper was in the upright position. It seemed symbolic—and probably expensive.

I'd wanted to snag photos on Highway 50 as the sun fled into the distant mountains. The high desert of Nevada is alluring. Highway 50 is known as the "Loneliest Road in America."

It probably isn't. Some of the routes through middle Nevada are far less traveled. It starts its cross-state run at Reno with the last town being Ely, over 320 miles. It used to be hundreds of miles between fill-ups, but towns have filled in.

The roads were clear to Austin, Nevada, 100 miles into Highway 50. The wind started to pick up after. I had no cell phone service. The light amount of snow that had fallen earlier was now blowing across the road. It lay on the pavement in stripes. The car lurched over each one, revealing the true nature of its alignment. I'd realized in Tahoe I needed tires and an alignment, but no one stocked the tire.

In the middle of nowhere Nevada, the odds were stacked even further against me. I kept on. I was the only one on the road.

The sunset I was after never came. The clouds never gave respite. Darkness fell, and visibility came and went. Road conditions had varied until the halfway point, but there was no thinking "I'll drive through this" any more after that. It had begun to snow, and the winds kept up.

In the distance two headlights were pointed off and down, illuminating the side of a berm. One headlight was askew. It was a semi pulling two separate trailers full of hay. The wheel on the driver side was pointed in a different direction, the tie rod obviously broken. Snow and dirt were shoveled up over the top of the bumper, about halfway up the grille. The driver must have dipped just one tire off. I drove past, then stopped, then backed up. I hadn't seen anyone on the road in over 30 minutes.

The truck idled, the only thing other than my car making any noise for miles. "Hey, man do you need help?" I asked. The return was in Spanish. His voice was absurdly cheerful, and upbeat, given the situation. I tried to offer help but the communication barrier was too much to overcome. I hoped someone was coming to get him. I simplified the interaction with "You okay?

He said, "I okay." I bid farewell with "buenos noches," and rolled on.

It was dry again 90 miles from Ely. I was going to be late. The next town I came to was asleep. The gas station was closed with pay at the pump available. I filled up and fixed my misaligned headlight. It was an empty gesture and unlikely to help in the blowing snow.

A forgettable green Ford Explorer pulled up, and a young woman with purple slippers hopped out. I wondered where she could be going alone at this time of night, in this place. She stood in the dirty slush, her heels and toes outside the fuzzy confines of her slippers. I quietly muttered "what are thooooose?" to myself. One hotel sat in the middle of town. There was one car in the lot.

The elevation jumped very slightly as I rolled by. The traction control light started up. It's giant triangle not blinking for seconds, but minutes. It was relentless. The car was riding on pure ice.

The differential in the C43 offered itself up, somehow allowing both wheels to weakly attempt to move the car out of the town and up the next hill. I got about a half-mile out of town and could go no further.

I didn't want my last words to be "what are thooooose?"

A brand new Cadillac Escalade pulled up next to me. I looked over at his tires. They were gnarly, with knobs out to the top sidewalls. The driver rolled down the passenger window.

I asked the guy inside if he wanted to trade vehicles. Clearly unimpressed at my attempt at humor, he declined and asked me if I had chains. I didn't. He implored me to go back, as it only got worse. I would. He took off in a manner I could only dream of.

Turning around on the steep incline wasn't easy. I was on a curve. Any input on the accelerator pulled me backward and sideways towards the ditch. In fact, anything I did at all induced slipping. I would have to back up into a J turn. I got about halfway through it when the car started to slide down the hill at a perpendicular angle to the road. I had no control. It was a tenuous, prolonged descent, angled slightly towards the ditch.

The tires caught the rumble strip at the side of the road and stopped. I put the car in reverse, muttering "so slow, so careful" as if I had to convince myself that getting stuck here would be an awful situation. I had AAA, but it would take all night for them to arrive. I'd have to walk back to my hotel, ashamed at all the choices I had made. I wasn't even sure decent tires would have helped at this point. I had less tread on my shoes than the tires did, and falling down over and over again all the way to the only hotel in town seemed pathetic.

Slowly, and carefully, I reversed horizontally across the road. Momentum and brakes took me the rest of the way back down the hill and into a town called, humorously, Eureka.

I rang the doorbell at the desk of the Sundown Hotel. It was 11:30 or so. I heard some rustling above me, and a woman clomped down some stairs and fell on to the stool behind the desk. Seventy-nine dollars, she said. Fine.

She mentioned they usually took care of the roads by 7 a.m., and that all of this weather was out really of season. It helped me feel less like an idiot, but not much.

It was cold in the room. The heat was off. Outside it was 25 degrees. Inside it wasn't much better. I poked the bed. The blankets were thin, and the hotel should have sprung for a new mattress years ago. I turned the shower on hot, which wasn't. I crawled into the shitty bed with the shitty blankets and thought about my shitty tires. I remembered the woman had told me she was going to bed, knowing there was nothing I could do short of sleeping in the car.

I feared dying from an exhaust leak in there, the world thinking I'd just had enough of this stupid used AMG and the snow. I was shivering. I checked the weather, wondering how far I'd be able to go the next day. There was a blizzard coming, and I-80, my route home, was closed. I hopped on DiscountTire.com and bought a set of tires and set them up to be delivered to a location in Salt Lake City.

I slept for 45 minutes.

I decided I'd head back the way I had come, where it had been dry, and then shoot straight north to I-80 via U.S. 276. The roads had deteriorated, but 276 was flat and it wasn't snowing. Oncoming truck traffic was brutal. Each one pulled snow off the road surface and blinded me for a few moments. I couldn't see the road, or anything out any of the other windows either.

Upon seeing one, I pulled as far right as I could and slowed to 10 mph. Despite the dangers from the trucks, 276 was mostly unpopulated, just like 50. Other than the road, there were little signs of humanity. No power lines, no buildings, and no real roads. In the distance, mountains sat stoically on their bedrock. The snow thinly veiled their shape, smoothing out much of their rocky surface. It was stunning.

In all my travels in the western U.S., I'd never seen anything like it. The mountains stood in contrast to the usually arid, desaturated scene. It made the previous night's problems seem like currency paid to see the view. With the car off there was near silence, the only sounds the wind whistling in and out of the rocks, brush, and drifts.

I-80 came, and with it, a sense of relief washed over me.

I got my tires and an alignment, so by the early evening I was on the road again. I drove until I couldn't, to Evanston, Wyoming. That hotel had heat and hot water, so things were looking up, until I learned the next morning that I-80 was still closed.

In the belief that I was going broke by not sleeping for free in my own bed, I decided I'd push on. The interstate was dreadful, even where it was open, it was covered in varying surfaces: hard packed ice, snow, small drifts, and slush. I pushed north around West Yellowstone, Montana near the northwestern-most point of Wyoming.

In Montana, I'd hook up with 12 or 94 and hope those interstates, which were also closed, would open. Just past West Yellowstone, I pulled over for a few photos. I observed the car would need spacers, because for some reason the rear wheels just didn't fill out the fender wells as they should.

The snowpack was still deep, but the roads cleared up the farther north I went. Driveways had 15 feet or more of snow lined up. It was deep enough you couldn't see the gas stations behind them.

At a gas station in Bozeman, Montana, I took a closer look at the stance. Through some of the sweepers on U.S. Highway 20 out of Yellowstone, I'd had some rubbing. The front tires had 245s on them, and so did the rear... at least on the passenger side. I stood up straight, not believing what I was about to discover. Indeed, the other side of the car had the 225s on it. Are you fucking kidding me?, I screamed inside my mind.

My morale was low, the interstates were closed, and now I was going to be stuck in a tire shop getting the wheels swapped around. Discount Tire apologetically paid for the work at another company's shop, and then some. Customer service, it turns out, is not dead.

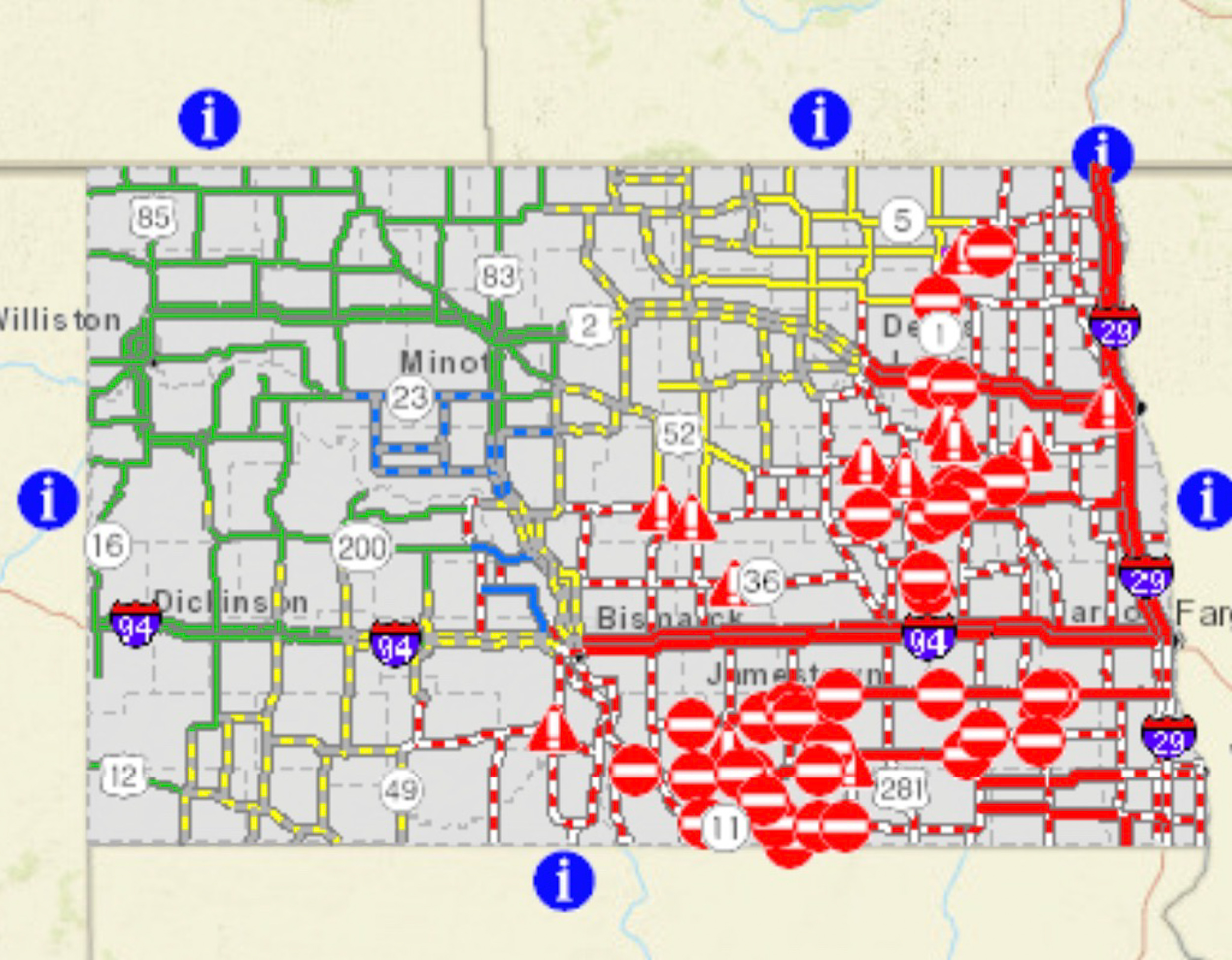

Miles City, Montana sits at the Interstate 94/U.S. 12 split near the Dakotas. One goes into South Dakota, the other North. Either way is a wasteland of a drive, and both were 100 percent closed. I pushed on towards Bismarck via I-94, where the closure occurred. With new tires (on the correct hub) and an alignment, the C43 finally felt like the car it was supposed to be. It ate up the miles.

For hours I violated the law on an absolutely barren stretch of interstate. There were no trucks and just a few cars. With no way through, people had elected to stay home, or just hole up. Truck stops were overflowing, far past their capacity. On ramps and off ramps were parking lots. Thus far the roads were dry and nearly perfect. About two hours short of Bismarck my radar detector lit up. I actually wasn't even speeding.

I made eye contact with the North Dakota State Trooper through my illegal tint. I laughed as I went by, elated that I wasn't going to get pulled over. I realized it was the first time I'd laughed, or said much other than "checking in" in several days. Several minutes later he pulled me over. While I was drifting towards the rumble strip, I raised my hands in disgust, my emotion finally getting the best of me.

The trooper asked if I'd like to explain my frustration in his police car. He was nice enough. He had a K-9 too. I suspected this section of road to be a drug corridor. I apparently smelled fine and was sent on my way.

Bismarck came up fast, and eventually I-94 opened like a gated, private road just as I rolled into the city limits. I was alone, and the newly opened interstate was mine. The roads were still garbage; there was little that would shake my resolve. There were no more obstacles, and I was six hours from home. I was just an idiot in a C43, but I'd made it.

So what do you take from this, if you want to buy an old car out of state and then drive it home? People do it all the time. I've certainly done it. A lot of preparation is needed, but in the end you never really know what's going to happen.

In hindsight, I should have addressed the tires and alignment first. I should have pushed harder for the previous owner to drop the car at a tire shop at my expense before I got there. I could have made that a deal breaker, and I can't imagine he would have balked. Following your own advice is often the hardest.

I was so enamored with finally finding a car that didn't suck I overlooked the exact thing I tell everyone to do: a pre-purchase inspection. A lot can go wrong in 2,000 miles. (It was 2,071, to be exact.)

Yet the solitude and ups and downs built a relationship with the car I wouldn't have otherwise. Even though I was a lot poorer, I didn't care. Driving isn't always about attacking, performance, and lap times. Sometimes it's just a way to experience things you never would have before, regardless of what road you're on.

Kristopher Clewell is a motoring journalist and photographer from Minneapolis.