The Car Loans That Never Die

Some credit companies have been shaking down car buyers for decades.

Richard Parker locked down a job at a Ford plant in the Detroit area, and, like most residents of the region, needed a car to get to work. It was 1991, and at the time he had shaky credit, so it was plenty difficult finding a company willing to lend him money for the purchase. That changed with Credit Acceptance Corporation, one of the largest subprime auto lenders in the U.S. But he never imagined he'd spend the next two decades paying for it.

In May of that year, Parker went to a dealership owned by Credit Acceptance's founder, Don Foss, in Redford, a Detroit suburb that borders the city's west side. After talking it over, a salesperson at the dealership scratched out an agreement for Parker to purchase a grey 1988 Chevy Blazer for $16,000. Parker put $3,390 down up front; Credit Acceptance agreed to finance a $9,198 loan at 22 percent interest, meaning Parker would have to pay about $3,500 in additional finance charges over the life of the 36-month loan.

The original MSRP for a 1988 Blazer was about $12,700, and like any used car, it had already depreciated in value by the time Parker had signed the sales contract. Parker knew it wasn't the best deal, but that's often the reality for a subprime car buyer with rough credit and not a lot of cash: dealers and their financiers are essentially free to set rates and purchases as they please. The reason for high-interest transactions, the dealer and lender's argument goes, is to account for the risk they're taking in financing a low-credit buyer's car.

Parker came to actualize the risk he'd taken on about two years after starting at Ford, when he fell ill with a serious virus and had to go on disability.

"I almost died," Parker told Jalopnik last month.

Then, he fell behind on his $351.28 monthly car payments. So, in late 1994, Credit Acceptance had the Blazer repossessed. He hasn't seen it since.

"That car's been gone, it's been 20 years," Parker said. But his debt hung over his head for more than two decades, growing in size and scope even as his wages and income taxes have been garnished, to the point where it was double the original loan's size—plus interest. Thanks to the terms of that loan, and Credit Acceptance's ability to involve a debt collector for nearly a quarter century, Parker kept paying and paying on a used '88 Chevy Blazer, a car note that never seemed to die.

"I know it was my responsibility and everything, but they make the most money out of people who are in bad situations," he went on. "And you would think they wouldn't go after them because, OK, they're in bad situations, how they going to pay for this?"

But Credit Acceptance found a way—and while the Blazer almost certainly ended up junked in a scrapyard, Parker's debt survived. He and consumer advocates see it as a system that sets subprime car buyers up to fail.

"If you buy these cars on the terms they're suggesting, it's going to amount to indenture that's going to be very difficult for the consumers to get out from underneath, let alone within the time of their contract," said Ian Lyngklip, a consumer protection lawyer in Michigan. "The cars aren't expected to last that long, they're going to fail before these contracts expire, and these people are not going to have the means to pay for them, without the benefit of having transportation."

"I don't understand how they can even get away with that. That's worse than loan sharking."

In December 1994, Credit Acceptance—which is based in the Detroit suburb of Southfield—filed a lawsuit against Parker in Wayne County Circuit Court, which has jurisdiction over Detroit, after he missed too many payments.

Two months later, a judge sided with Credit Acceptance, and ordered Parker to repay $13,053 (the remaining balance by then, having already ballooned above the initial $9,800 loan), plus interest and attorney costs.

It's nothing new to point out that subprime car buyers are routinely portrayed as the main actor at fault in a lending transaction gone awry. But the reality of the situation is far more complicated: it's not that subprime buyers want to pay an absurd amount for a cheap beater, it's just all they have access to, and often the terms of subprime loans are much more predatory and damaging than a prime loan would be.

And for most working Americans, a car is a necessity, not a luxury. Most people—about 85 percent of adults—use a car to get to work, so those with shaky credit take out a loan for a car at with a sky-high interest rate. If a dealer doesn't step in to ensure they're being put in a car they can afford, well, the buyer may be driving off the lot in a financial deathtrap.

That's why Parker's situation is emblematic of the contorted equation that drives subprime auto lending: an individual makes a mistakes or falls into financial trouble—say, they lose their job, get sick or go through an expensive divorce—and that trouble takes a hit on their credit rating. To rebuild their credit rating, they try to take on a car note, an argument deployed by lenders to support financing subprime auto purchases. But then higher interest auto loans are associated with a higher chance of default, and a default could lead to their car being repossessed, and the repossession makes it increasingly likely they'll file for bankruptcy, and so on.

Credit Acceptance's aggressive pursuit of buyers for nonpayment is widely acknowledged as a well-greased machine, and it's built into the company's business model: The company previously said it repossesses about 35 percent of all vehicles it finances.

Once Credit Acceptance had secured a judgment against Parker, the company was able to start garnishing up to 25 percent of his wages and tax returns to pare down the remaining balance—and keep doing it until the judgment had been paid off entirely or Credit Acceptance, for whatever reason, drops it.

Parker's case is an extraordinary example of how that practice materializes, but it shows just how far Credit Acceptance will go to recoup whatever costs it can.

By August 1999, when Credit Acceptance asked the court again to order his income tax returns garnished, Parker's balance had increased to $16,781. By April 8, 2004, thanks to the exorbitant interest rate applied to his original sales agreement, it spiked again to $25,595.

Court records show that a garnished payment was applied toward the balance on April 21, 2004—which Credit Acceptance took as "acknowledgment of the continuing vitality of the debt" underlying the initial judgment, the company wrote in a court filing, meaning it believed Parker was still good for the loan.

"What they do, right before it drops off, they just re-file it again," Parker said. "That's how they keep doing it, and I never understood how they could do it."

That's because Michigan law allows it. Garnishments can happen for 10 years, the statute says, but because of Parker's 2004 payment, Credit Acceptance argued in court a year later that the judgment against him for the remaining balance should be renewed. It was effectively a request to continue punishing him for doing what's ostensibly the right thing: if Credit Acceptance had been unsuccessful in obtaining any money through a garnishment, the lender would no longer have had legal recourse for the outstanding balance of the loan.

On April 22, 2005, the court again sided with the lender, ordering Parker to continue paying back a judgment that had by then grown to $27,315.

Credit Acceptance didn't let up. In October 2012, it filed another request with the court to garnish Parker's income taxes. At that point, he'd had $17,575.32 garnished—nearly double the amount of the original loan—but due to the interest costs accrued from the original judgment, records show, he still had $9,781.96 to go.

The last garnishment request Credit Acceptance made was in October 2014, after Parker had an additional $9.40 garnished, leaving his remaining judgment balance at $9,864.17—more than the original loan he'd received from the lender 20 years prior.

Credit Acceptance didn't respond to a request for an interview nor a series of questions from Jalopnik.

"Ain't that crazy?" Parker, now 49, said with a laugh. "I don't understand how they can even get away with that. That's worse than loan sharking."

Rampant fraud across the banking industry and unfettered access to credit for home subprime buyers led to the housing industry's demise a decade ago, but lenders never turned the spigot off for auto lending.

Once the dust settled from the 2008 crash, the financial industry shifted its gaze to low-credit buyers, and in turn, car sales picked up. The focus on subprime auto lending brought record sales across the car industry in 2016 and 2017. Now Americans hold $1.24 trillion in auto loan debt.

Credit Acceptance and other lenders argue they're filling a crucial area for low-income buyers by providing them an opportunity to obtain credit from a traditional source.

"Our financing programs are offered through a nationwide network of automobile dealers who benefit from sales of vehicles to consumers who otherwise could not obtain financing," Kenneth Booth, the company's chief financial officer, wrote in May.

But economists and financial institutions themselves have watched as the newfound trend led to a sharp rise in defaults. Today, a record 6.3 million people are 90 days or more behind on their auto loan—an increase of 400,000 car buyers from just a year prior.

Credit Acceptance itself has long faced lawsuits over its lending practices, and attention from regulators has picked up in recent years. The Federal Trade Commission in 2017 opened an investigation into the company's use of GPS starter interrupter devices, which can disable the ignition of a car owned by an owner that fell into arrears.

And in April, Credit Acceptance disclosed that an investigation had been launched by the New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) financial frauds & consumer protection division. The company said in filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission that the NY DFS believes Credit Acceptance violated laws related to the fair lending act, misrepresented to consumers information related to GPS starter-interrupt devices, and provided inaccurate information in the court of a DFS audit.

"I had enough of them garnishing my checks. That's what made me do the bankruptcy."

"We have not received any written communication from the DFS regarding its conclusions," Credit Acceptance said in the filing. "We are cooperating with the inquiry, including through the exchange of certain written correspondence. We cannot predict the eventual scope, duration or outcome at this time. As a result, we are unable to estimate the reasonably possible loss or range of reasonably possible loss arising from this inquiry."

A DFS spokesperson told Jalopnik the agency "does not confirm or comment on whether an investigation is in progress."

Whatever the case, the company's business model has been good to its bottom line. Credit Acceptance has a market value of $8.66 billion and, in 2017, it yielded $470.2 million in net profits.

Company execs have done well, too. CEO Brett Roberts has a compensation package worth $54.2 million. Foss, the Credit Acceptance founder, made $128 million last year, after selling off his company shares upon announcing his retirement.

The company rarely provides interview opportunities with execs to discuss its business model. But Roberts offered the standard line about providing opportunities to car buyers in 1999 for a story from the Washington City Paper, saying Credit Acceptance has received praise from "countless" consumers.

Roberts told the newspaper that consumers, "because of CAC's willingness to provide funding, were able to purchase a reliable automobile, reestablish their credit rating and consequently move their lives in a positive direction."

But Toronda Seahorn can't say her life has been moved in a positive direction as a result of the lender.

In 1998, a then-early twenty-something Seahorn went to a dealership in the Detroit area with her sister's friend, who'd asked her to co-sign on a vehicle. She assumed it wouldn't be a big deal, but Seahorn learned a few months later that the friend had, as she put it, disappeared.

"I couldn't get in contact with him," she said. "I just had this debt hanging over my head."

Credit Acceptance went to court and secured a judgment against her for the loan's balance, but Seahorn said wasn't even made aware of the issue until her checks started getting garnished.

"They were sending letters," she told Jalopnik. "I had my sister's address. Once I moved from my sister's address—that's the last address they had—and I hadn't been checking my mail frequently, but once I seen I was being garnished I'm trying to figure out where it's from, and it's them."

Seahorn never managed to track down the family friend who took the car, so the lender kept taking her into court. Now 42, Seahorn said she'd managed to delay one of the company's garnishment attempts several years ago, "but it was only stopped for so long before it started up again."

A decade after the initial suit was filed, records show Credit Acceptance secured a renewed judgment in 2008 against her for $4,704. The garnishments continued, Seahorn said, "until I got to the point I had to figure out what to do."

"I had enough of them garnishing my checks," she said. "That's what made me do the bankruptcy."

When she filed for bankruptcy in 216, she reported having $27,874 in liabilities, including $3,057 in student loans, various credit card debt, a hospital bill, and a car payment to get to work, where she earned $1,852 per month after taxes. The Credit Acceptance judgment is what tipped her into insolvency, she said.

The situation is a sharp deviation from what prime buyers, who have lower-interest payments, may go through. A lender still has recourse to go after a prime car buyer if they fall behind on their monthly bill, including repossessions, but studies have shown high-interest loans are associated with a higher chance of default. And that puts subprime car buyers, who are often already poor, at an extra risk.

Subprime buyers may struggle to secure a loan from a traditional bank to the shop around for their best deal, so they're left to dealers to arrange terms for them. And most states have regulations for auto lending that allow dealers to set whatever interest rate they want, even though there's statutes barring usurious terms.

Taken together, the overarching risk of taking on a loan like this—one deemed essential for consumers to get to work or the doctor, and, in turn, fix their credit so they never have to accept such burdensome terms again—is that subprime lenders like Credit Acceptance have the ability to ensure the consumer pays back the loan, even if it takes chasing them down for the better part of their adult life.

Twenty years on, at this point, Seahorn couldn't even name the make or model of the vehicle financed by the loan. She just knows the loan and the aggressive collections practice by Credit Acceptance to recoup whatever it can pushed her into bankruptcy.

"I can't remember what car it was, honestly," she said. "It's been so many years."

It isn't known how many collections lawsuits are filed against car buyers each year, but a study on Credit Acceptance that asserted the company's finances are shaky found more than 18,000 were levied in Detroit between 2007 and 2017.

"It's devastating," said John Van Alst, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center and expert in auto finance issues. "First of all, from a practical standpoint, what it does to their credit and their ability to try to get another car to get to work and to keep making the payments, that is huge."

"If their wages are getting garnished," Van Alst went on, "it's before they even have a chance to decide what bills they're trying to pay and anything else. So that can be really devastating, as well. It makes things really difficult going forward, and most of these people are obviously people who need a car in the first place, or else they wouldn't have gotten one."

Another buyer Credit Acceptance sued in its backyard is Detroit native Demarco Cotton, who, in 2008, took out a $5,000 loan through the company for a used car.

Living in Detroit, Cotton's accustomed to the shoddy, fractured public transit system associated with the city and its surrounding region. Working for a cleaning business, he said he needed something reliable to get around town with ease.

"From a practical standpoint, what it does to their credit and their ability to try to get another car to get to work and to keep making the payments, that is huge."

But after only two weeks on the road, the transmission of his Pontiac Grand Am broke. He said he took it back to the dealer to get it fixed, but a couple days later, it gave out again.

"I never even had a chance to make a payment," he said. The dealer told him to have it taken to a lot, while they contacted Credit Acceptance. Cotton said he stopped making payments at that point. Within a couple years, the lender took Cotton, 30, to court and got a $9,400 judgment secured against him. Working three jobs at the time, Cotton said the lender took a massive chunk out of his wages. He wasn't sure what to do.

"For a long time, I was just like, 'I'm going to face it and accept my debt,'" he said. "I was trying to, but any time I would get any money, no matter where it comes from, if it was a check from Walmart [where he worked as a customer service manager], or from another job they would still try to take it." The lender tried to dock his 401k account at one point, he said.

Cotton even took drastic measures that, at first, could seem counterintuitive, but underscores the reality of how the garnishments can make someone exceedingly desperate.

"I had to actually quit my job and I forced myself out of there by getting fired for attendance, basically, not showing up," he said. "Just abandoned my job, and, in transition, I went to a hotel to make $3 less per hour just so I could avoid the garnishment."

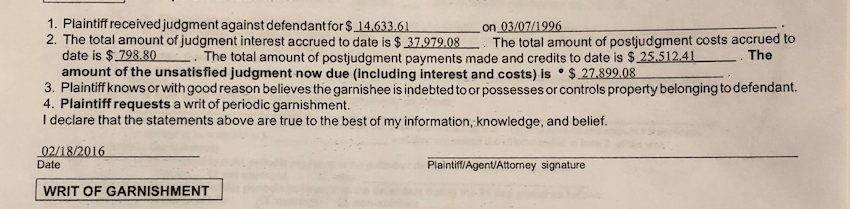

Collection cases brought by Credit Acceptance could even seem arbitrary, on occasion. Take, for example, a suit brought by the lender in 1996 to collect on a Detroit resident's $27,834 loan for a 1991 Chevrolet Corvette due to nonpayment.

In March 1996, the judge ordered the resident to pay a $14,633 balance remaining on the loan. By 2012, about $13,000 had been repaid, but due to the 22 percent interest on the original sales contract for the Corvette, the resident still had a $33,619 balance remaining.

Four years later, in February 2016, Credit Acceptance asked the court to garnish the resident's wages from his job at FCA. By then, he'd repaid $25,512—on a judgment that originally started at $14,633.

That June, for reasons that go unexplained in court records, Credit Acceptance abruptly reversed course, and told FCA to stop garnishing the resident's wages. With a $27,899 balance remaining, Credit Acceptance wrote in a filing to the court and said only that the judgment "has been satisfied in full."

Cotton said he couldn't escape insolvency with the garnishments from Credit Acceptance hanging over his head. This past April, he filed for bankruptcy, which tampered down the collection efforts. The auto loan and Credit Acceptance's collection efforts, however, have still left a lasting mark.

Nearly a decade after the debacle began, Cotton said getting Credit Acceptance "off my back is a victory, but I kind of regret it at the same time."

In early August, he started looking into possibly buying a house. But most lenders pointed to his bankruptcy as a problematic factor that could inhibit his chances of securing a mortgage, he said.

"I wouldn't have filed bankruptcy if it wasn't for Credit Acceptance," he said.

This story was originally published on September 25, 2018