The Brown Bullet Is A Reminder That Racing's History Has Always Been Segregated

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

When Rajo Jack first got behind the wheel of a race car, it was only because he'd spent years getting to know the people at the track, who decided they liked him enough to let him get behind the wheel. As a Black man in California during the 1920s during an era where it was physically dangerous for him to drive alone to the race track, he was lucky to have even gotten that far. That's the story Bill Poehler tells in The Brown Bullet: Rajo Jack's Drive to Integrate Auto Racing.

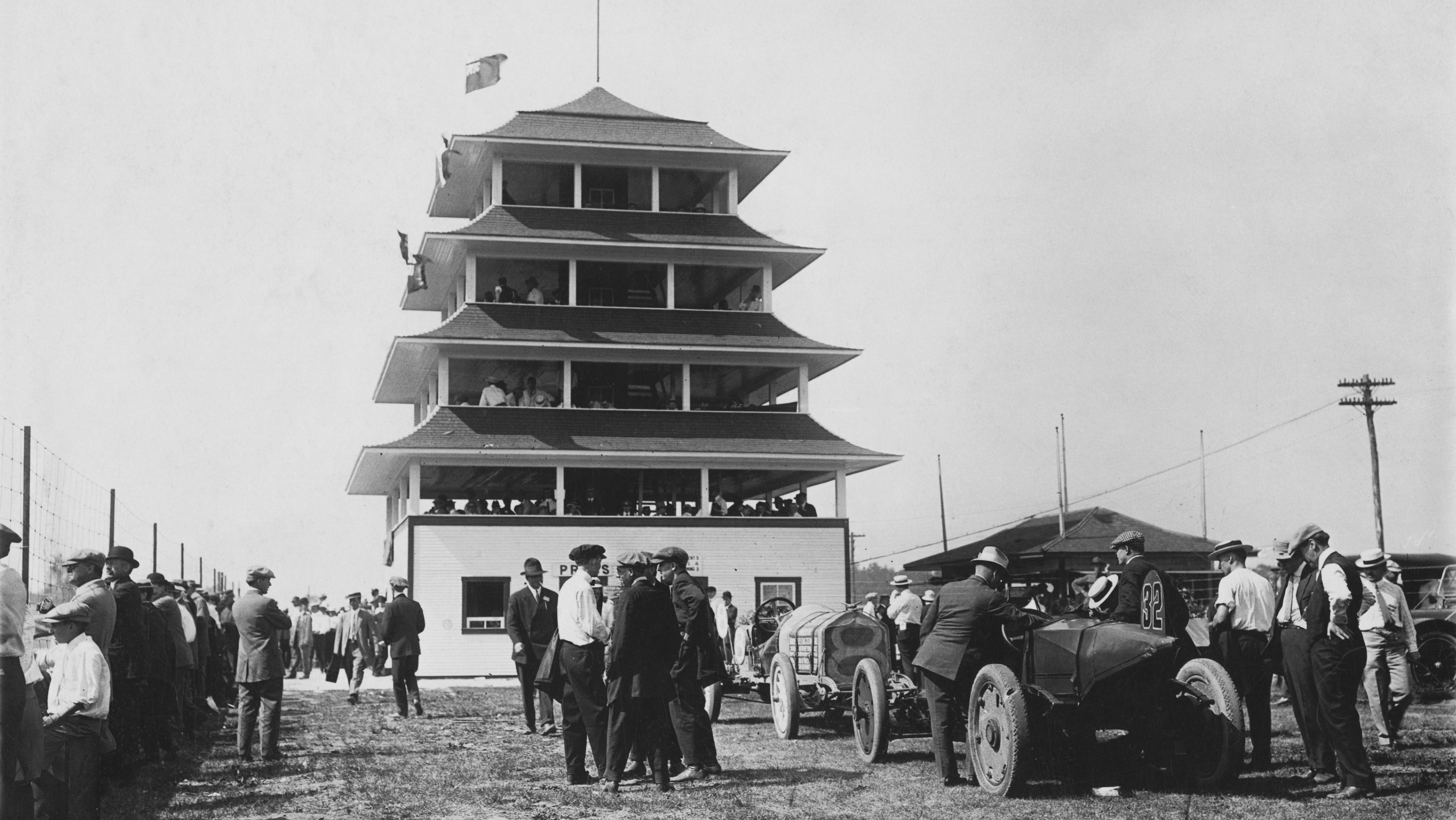

Back in the early 1900s, the American Automobile Association (AAA) sponsored all the big races in the United States—including the Indianapolis 500. To contest those races, you needed a AAA racing license. To work those races, you needed a AAA mechanic's license. If you didn't get those things, you'd be forced into 'outlaw' races, where racers couldn't guarantee that the promoters would actually pay them prize money instead of just running off with it after the race.

The problem was, the AAA pointedly did not allow Black racers to compete. Their license applications would be rejected immediately. If the AAA didn't realize the driver was Black and accepted the license accidentally, the driver would still be disallowed from entering the pits at the track. That's the kind of life Rajo Jack was forced to live driving as a Black man in the early 20th century.

Jack's career started off unconventionally. His Texas-based family, the Gatsons, thought they could find better prospects in California and were proved wrong. They only lived in the Los Angeles area for a year before returning home, but that was long enough for young Dewey Gatson (who took on tons of different names before settling on Rajo Jack) to meet a man named M. B. Marcell, a part-time photographer and full-time scammer. Marcell, a white man, promised Dewey Gatson a job when he got older.

And Dewey took him up on it. He walked out of his family home at age 15 and took every cent he had to California to hunt down Marcell... who had moved to the Portland area to avoid getting in trouble for a scam he'd been caught in. Marcell's current grand plan was selling "medicine" that could supposedly cure every ill, which he marketed via a traveling circus. Marcell didn't remember young Dewey Gatson, but he needed a hand driving all the trucks to different locations. To stay out of trouble, he posed as a Portuguese man—sufficiently exotic enough that anyone who gave him a hard time about his skin color would have to think twice.

He got his start behind the wheel there, but he really started earning money selling Rajo heads, which were non-stock performance headers that could be fitted to Ford engines to give racers a leg up. Dewey Gatson would receive $10 for every head he sold and $10 for every head he fitted. He started raking in the money. And with that extra cash lining his pocket—and a new name, Rajo Jack—he hit the racing circuit to give it a try himself.

The only qualm I really had with this book is the fact that there are sections that come across as just a straightforward recounting of Rajo Jack's races, but that issue has less to do with the writing than with the nature of the subject. Jack was a man who went by countless different names, both intentionally and unintentionally. He didn't keep a diary, and he wasn't a frequent interviewee the way many racers are now. He didn't have any children to tell his story, nor did anyone in his immediate family. And he was a person that a fair amount of folks in the racing world likely would have preferred be forgotten. When he died, it was entirely possible that his legacy could have died with him.

Brown Bullet is, however, a great book highlighting the more insidious side of racing back in the day. I've read tons of books about that era of racing in the United States, and they never touch on the fact that the AAA was rooted in some serious antagonistic sentiments. No women, no people of color. Rajo Jack, one of the best racers in the country at the time, was forbidden from ever really growing professionally. He managed to strike up deals with white promoters and smaller racing organizations to pay him appearance fees, but no matter how many races he won, Rajo Jack stagnated.

It's hard reading about the tail end of his career. He went from being a billboard-advertised main attraction to a has-been pretty damn quickly. A rock smashed his racing goggles and filled one eye with glass. Doctors saved it, but he tried a motorcycle race, crashed, and ended up asking to have that eye removed. He went to the Midwest chasing bigger purses and crashed in his first race, leaving him with a broken arm that he could never fully extend again. His marriage failed. World War II left him unable to race for years, and when he got back on the track, his equipment was so outdated that he was often uncompetitive.

It's hard to read that, knowing that he could have found success at the Indy 500 or even as a AAA champion but that he never got a chance because of his race.

Brown Bullet is an excellent read to give you the context behind modern racing in the United States. It's the biography of a man who did a hell of a lot with the little he was given but could have been so much more. And it's a reminder that the faces spotting the Borg Warner are almost exclusively white men for a reason.