The Boeing 747 'Queen Of The Skies' Has Reached The End Of The Line

Production is soon coming to an end on an aircraft that helped define a generation of flying.

Over 53 years ago, the Boeing 747 took its first flight with a destination for the history books. The aircraft had earned the nickname "the Queen of the Skies" and became synonymous with the term jumbo jet. But with just four aircraft left in Boeing's order book the ride has come to an end for one of the most majestic planes put into production.

Back in March, Boeing 747-8F freighter, registration N633UP, rolled out of a paint shop. Its fresh livery was that of UPS Airlines, the aviation arm of the logistics monster. This aircraft is important, as it's the last Boeing 747 that UPS will get and it's one of the last that anyone will receive new. There are just four more 747s left in Boeing's order list — all freighters bound for cargo airline Atlas Air. Then, the books will close on the jet that helped define an era of air travel. Let's remember the Boeing 747, the Queen of the Skies.

Depending on who you ask, the 747's story starts with the iconic Boeing 707, a plane that kicked the tires and lit the fires of American commercial jet aviation. There's precedent for this, but we'll start with another aircraft that gave some inspiration.

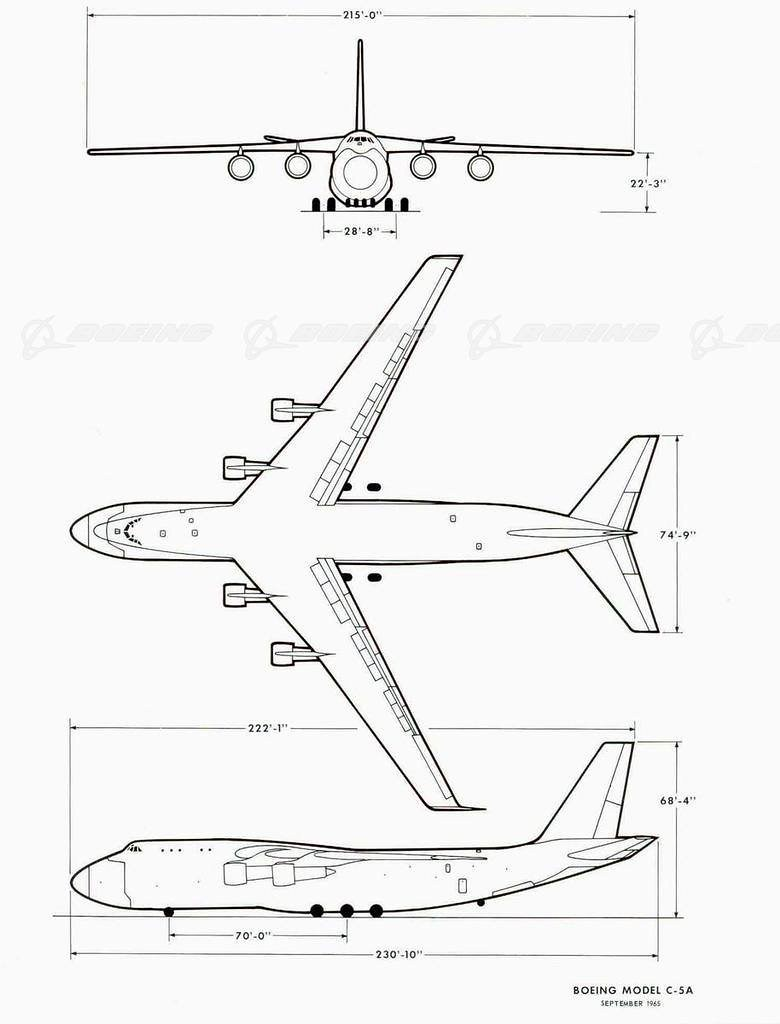

In 1961, the U.S. Air Force began looking into a replacement for the Douglas C-133 Cargomaster and a complement to the Lockheed C-141 Starlifter. Many aircraft manufacturers took on the challenge. It took until 1963 for the military to finalize what it was looking for in its Request for Proposal for a large military transport aircraft. The project was dubbed the Cargo Experimental-Heavy Logistics System, or CX-HLS.

Boeing, Douglas, General Dynamics, Lockheed and Martin Marietta all had their own bid for the best CX-HLS before the military pared it down to just Boeing, Douglas and Lockheed. Due to the requirements of the aircraft needing to be loaded from up front, all three designs placed the cockpit above the cargo area. Lockheed went with a spine that ran the length of the fuselage while Douglas and Boeing elected for cockpit pods.

While Boeing was competing for the CX-HLS, interest for a massive passenger aircraft came from Pan American World Airways. CEO Juan Trippe was looking to capitalize on the explosive growth of commercial air travel with an aircraft double the size of the Boeing 707. Pan American was the launch customer for the 707 in 1958 and the airline also wanted to solve the problem of airport congestion.

Boeing lost the bid for the CX-HLS, but it wasn't going to let the military stop it. Pan American placed its order in 1966, kicking off 747 development.

Boeing notes that the 747 is intentionally different from the previous military project, but a few attributes made it over. The obvious one is the hump for the cockpit and the upper deck. High-bypass engine technology then being developed for the CX-HLS would find a home in the 747 in the form of four 43,000-pound-thrust Pratt & Whitney JT9D-3 turbofans.

Pan American's Juan Trippe had some say in the design, asking for the plane to be able to carry 400 passengers. Another benefit, noted by Northwestern University, was that by going huge, Pan American would be able to reduce the price of a ticket per seat. And with cheaper prices, more people could enjoy flight. As noted by learning site Infoplease, Boeing at one point saw the aircraft having a full double-decker design, scaling back to the signature hump after the potential for upper deck evacuation problems arose.

Boeing agreed to deliver the first 747s to Pan American by the end of 1969. When that agreement was reached, the aircraft manufacturer had just 28 months to design and build the plane, from Boeing:

The 747 was the result of the work of some 50,000 Boeing people. Called "the Incredibles," these were the construction workers, mechanics, engineers, secretaries and administrators who made aviation history by building the 747 — the largest civilian airplane in the world — in roughly 16 months during the late 1960s.

The 747 took its first flight in 1969 before deliveries started to Pan American in 1970, changing aviation history.

Boeing has produced a wide array of 747s over the years from the stubby 747SP to the 747-400 Dreamlifter, a modified 747-400 that carries 787 Dreamliner assemblies on its wings. The 747 has been used for travel all over the world and has been featured in countless forms of media. Even wacky Soul Plane used a goofy CGI version of the plane.

For decades the jumbo jet was the pinnacle of air travel.

Unfortunately, the march of technological advancement and a change in how people fly has made the quad-engine jumbo jet an endangered species.

Today, twinjets have more capability than they used to, allowing them to cover the routes that were once reserved for planes with three or more engines, from Simple Flying:

At the time the 747 was designed, twin engines were severely limited in operation and not permitted to fly more than 60 minutes away from a diversion airport. This made transoceanic flights the domain of the quadjet.

This has changed. ETOPS (Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards) regulations were introduced in the 1980s and recognized the improved performance and reliability of twin-engine aircraft. The first rating given to the 767 permitted operations up to 120 minutes from a diversion airport. This has increased today, with ratings of up to 350 minutes for the Airbus A350.

On top of that, planes like the 747 work best on a "hub and spoke" model. In this operational model, people fly from hub-to-hub on a large aircraft, then board something smaller to reach their final spoke destination.

Today, you can board a flight that works from point-to-point without necessarily needing to connect at hubs. Of course, these flights will often have fewer people onboard, making such large planes unnecessary.

That means that the numbers of 747s in the sky are dwindling. The type's largest customer, Japan Airlines, retired its last aircraft in 2011. Some others have retired their passenger 747s, but still have freighters flying.

The pandemic was a huge hit to the world fleet as the decline in air travel allowed airlines to retire their 747s earlier than planned. You can still ride aboard a 747-8 with Air China, Korean Air, and Lufthansa. And if you like things old school, the 747-400 is still flying with Air China, Air India, Asiana, Rossiya and Thai Airways. And who can forget that the President will be flying on a version for years.

The end of production means the end of an era. But don't cry just yet. With a total of 1,568 of them delivered as of this year, we're bound to see the beauty for years to come. You may not be able to fly on one once passenger variants are fully retired, but if you hang around an airport you'll be sure to catch a freighter taking to the skies with that sublime hump.