The Best Concept Cars Of The 1930s

A decade defined by art deco beauties and occasionally goofy technology

Auto shows have been around almost as long as the American auto industry has existed. The first one was put on by an auto dealers association in Detroit in 1907, and was simply called the Detroit Auto Show back then. At first, such shows were like mega dealerships, bringing together lots of automakers in one place all vying for attendees orders. In the 1930s however, as aviation and other technology seemed to develop at a comparatively rapid pace, automakers began to have been dreaming big dreams about what cars they'd like to build, if only it were the future.

The Great Depression and the rise of WWII couldn't slow down the creation of the concept car as an object of experimentation and vision, though those two world-rattling events sure did try. Here are just a few beautiful flights of fancy in automotive form from one of the toughest decades in global history.

The Schlörwagen

This fast-looking pod was designed by Karl Schlör, an engineer at Germany's pre-war Aerodynamic Research Institute. Schlör wanted to create a car with the same aerodynamics as an airplane wing. He managed to squeeze a drag coefficient of just 0.186 out of his wagen. As Mercedes Streeter noted in her story on the Schlörwagen: "To put that into perspective, the Mercedes-Benz EQS is touted as the most aerodynamic production car right now with 0.20."

Now that's slick. So slick in fact, that the car was never built as strong headwinds could knock it right off the road. It is believe the car was scrapped following WWII.

This goofy three-wheeled people hauler was supposed to be a flying car someday. Designed by architect Buckminster Fuller using his own trust fund, the Dymaxion (named for dynamic, maximum, and tension) was a death trap at high speeds or in high winds. Autoweek took a replica for a drive, and it's obvious where the problem is:

The Dymaxion car's bizarre configuration should be the first clue that it's not exactly going to be the most stable thing on three wheels. The reverse-trike configuration is a decent start, but it all quickly goes to hell: though it is front-wheel drive, the Dymaxion car's Ford V8 is way in the back — just ahead of the singular rear wheel, which is cradled by a suspension system cobbled together from Ford components.

That rear wheel is how you steer the car, for some reason. In theory, this front-wheel-drive-rear-wheel-steering configuration gives the Dymaxion car a very tight turning radius. In practice, it walks all over the road, even at the low speeds (20 mph to 35 mph) we held it down to; crowned or rutted road surfaces are extremely difficult to negotiate.

Keeping Bucky's beached whale pointed straight demands slow, deliberate and constant steering adjustment. At the back of our minds there was the fear that a quick input or an overcorrection would send the car swinging back and forth across the road like an out-of-control pendulum, ultimately leading to our horrible, embarrassing death. This fear was not unfounded, as the car the Lane Museum replicated most closely (prototype number one of three built) killed its driver back in 1933.

Yup, one of the three prototypes built back in the '30s was hit by another car, killing the driver of the Dymaxion who was even wearing a seatbelt at the time (a very rare safety precaution for the 1930s.) Fuller made a lot of wild claims about his car, like how it could travel 90 mph and squeeze incredibly milage out of a totally unmodified flathead Ford V8. Sure, he sounds like a shyster, but aren't all dreamers and visionaries a little bit crooked as well?

1938 Buick Y-Job

The Y-Job isn't just a concept car, it helped create the modern idea of what a concept car should be: Batshit wild ideas straight from the future. Here is how Jason Torchinsky described this wild concept that came out of Depression-era Detroit:

The father of the Buick Y-Job was Harley Earl, head of GM's "Art and Color" department and a man who later would order the chrome trim on Oldsmobiles by the pound. Earl saw that styling was increasingly driving consumer's purchases of cars after the depression, and decided to create a "concept car" which would be used to try out new styling ideas and exercises, new technologies, and gauge public reaction. Based on this, he didn't just create a concept car, he created the entire notion of concept cars, and defined their fundamental purpose and goals: Try out something crazy, and see what happens.

The Y-Job (named because most experimental cars were named X-something, so he just went one letter up) was built in 1937, and contained styling elements and ideas that GM would still be pulling from well into the 1950s. It had GM's first horizontal grille, motorized pop-up headlights (though the Cord 810 had hand-cranked ones just a bit earlier), radically long, low proportions, no runningboards and flush door handles for super clean lines, very deco chrome detailing, a motorized, concealed convertible top– this thing was packed full of radical, exciting ideas. Earl drove it around as his own personal car for a while as well, which islets one thing the Y-Job had over most later concept cars, which often have no real working drivetrain at all.

GM would use ideas it developed on the Y-Job for decades to come, with other automakers copying the more attractive elements as well.

1939 Mercedes-Benz T80

Meant to make Germany's first attempt at a land speed record, the T80 never moved under its own power thanks to, you guess it, the outbreak of WWII. Built by Mercedes-Benz and developed and designed by Ferdinand Porsche, the T80 gained a cool nickname and nationalistic paint job from an unfortunate source—Hitler called the T80 Schwarzer Vogel, or Black Bird. The land speed attempt was set for 1940, and would have been Germany's first attempt at a land speed record. Then came the war.

The Germans estimated that the T80 could hit speeds of 465 mph, a record that would not be achieved until 1965 with Craig Breedlove's run in a jet-powered specially designed vehicle. Guess we'll never know, as this wild vehicle lost its DB 603 engine in 1940. It's now on display at the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart.

1934 Porsche Type 32

It just wouldn't be a list of legendary 1930s concepts if something sort of related to the VW Beetle wasn't featured. This is another design idea from Ferdinand Porsche and you can clearly see design cues—along with the torsion bar suspension and air-cooled engine—that he'd bring back in 1935, when he received a commission to design a Nazi-subsidized "People's Car."

1932 Helicron #1

Yes, that is a car with a giant propeller on it and yes, Lane Motor Museum takes care of this incredibly concept as well. Our own Jason Torchinsky got to actually drive this incredible vehicle. It turns out, propellers are just a crappy way to move ground-based vehicles. This one-off never had a chance:

The Helicron is a one-off built by an unknown French airplane enthusiast back in the 1930s. It's based on a Rosengart chassis, but flipped backwards, so the steering gear is at the rear. Originally, the car had a flat-twin engine, but that was replaced with a Citroën GS flat-four after it was discovered and restored in 2000.

A propeller is fantastic when you're not actually in contact with anything solid, like the ground, but given the choice between pushing against the big, hard ground and pushing against the mix of nitrogen and oxygen we call air, I'll take ground every time.

The crazy thing about driving the Helicron—and I suspect every propeller-driven car—is that it reverses all the sensory stuff you expect when driving. For example, when I was trying to get up a hill in the Helicron, I had the throttle pegged, and I heard the engine roaring at maximum revs, and felt the wind blasting my face from the propeller spinning.

It was just like going really fast in any old, open car, with the one difference that I was barely crawling up a hill.

Physics! Why do you have to make a mockery of every cool and good idea.

Pierce-Arrow Silver Arrow

Pierce-Arrow looked around at other luxury automakers going belly up during the Great Depression and thought "Nah, never happen to us. What we need is an even more ridiculously luxurious car to cheer everyone up!"

Enter the Silver Arrow on the scene of the 1933 New York Auto Show. The car's slogan "Suddenly it's 1940!" really drives home how excited everyone was to get that miserable decade over with only three years in. From Auto Evolution:

Conceived at a time when Piece-Arrow was losing millions, the Silver Arrow was penned by Phil Wright, who was still in his 20s, and immediately approved by Harley Earl. With fully integrated fenders and headlamps mounted high with the line flowing up and back past the doors, the Silver Arrow resembled no other car from the company. And no other car available at the time, for that matter.

The car also featured a few groundbreaking aero features, such as flush-fitting rear fender skirts, recessed door handles (common on modern cars), and a sharp sloping rear section. The cabin was flanked by a V-shaped windscreen in the front and a slit-like window in the rear. The latter was pretty useless in terms of visibility, but it added to the car's futuristic, Batmobile-like styling.

Pierce-Arrow's out-of-the-box thinking continued with the placement of the spare wheels. Most cars of the era had spares mounted on the rear (attached to the trunk box) or placed on the front fenders, which were individual units, separated from the body. The Silver Arrow had them hidden in lockers in the impressively long front fenders. These could be opened by remote controls in the dash.

Art Deco in general is a bitchin' design period, and the Silver Arrow is the pinnacle of the style. The pricing however, made the five examples sent to the auto show completely out of reach of most of America then, even the formerly very wealthy. Pierce-Arrow would go belly up in 1938 after producing a watered-down version of the New York Auto Show car.

1932 Chrysler Airflow Trifon Concept

The famous Airflow concept is remarkable as it is one of the first cars designed using wind tunnels.

The car came with remarkable modern details according to Car and Driver:

Probably the best-known American streamliner is the too-futuristic-to-sell-well Chrysler Airflow. This is the prototype of that groundbreaker, built to test out engineer Carl Breer's wind-tunnel-tested shape along with numerous other innovations like a rear-hinged hood, quasi-unibody construction, and a one-piece curved windshield. The car was licensed with the named Trifon (after one of the project managers) in order to throw the competition off. This historic piece belongs to the Walter P. Chrysler Museum.

Chrysler would go on to use the Airflow name, as well as what it learned about aerodynamics, on some beautiful, but commercially unpopular vehicles. Recently, the brand brought back the Airflow name in an EV concept aimed directly at Tesla's Model Y and Model 3.

GM Futureliner

These beautiful art deco buses were built by GM to showcase amazing new technologies across in the country. After a pause for WWII, the company sent out the Futureliners again for what GM called its "Parade of Progress." GM built 12, of which nine exist today, according to The Drive:

A little context is necessary to complete the picture. As I already mentioned, a dozen GM Futurliners were originally built to tour the country and show off new technology back in the 1930s, and after a pause for WWII and a vital postwar restyle, they crossed the nation again in the Parade of Progress to tell Americans about the exciting future of everything from refrigerators, to jet engines, to heavy industry and more. One whole side of the Futurliner opens up to show a diorama-type display, so outside of that they're fairly useless vehicles. But man, there is something magnetic about the industrial optimism the Futurliner exudes. And even today, its design holds up—undeniably from the past, but also timeless.

GM never intended to actually build the Futureliners. After the Parade was done, the remaining buses slipped into private collections and museums.

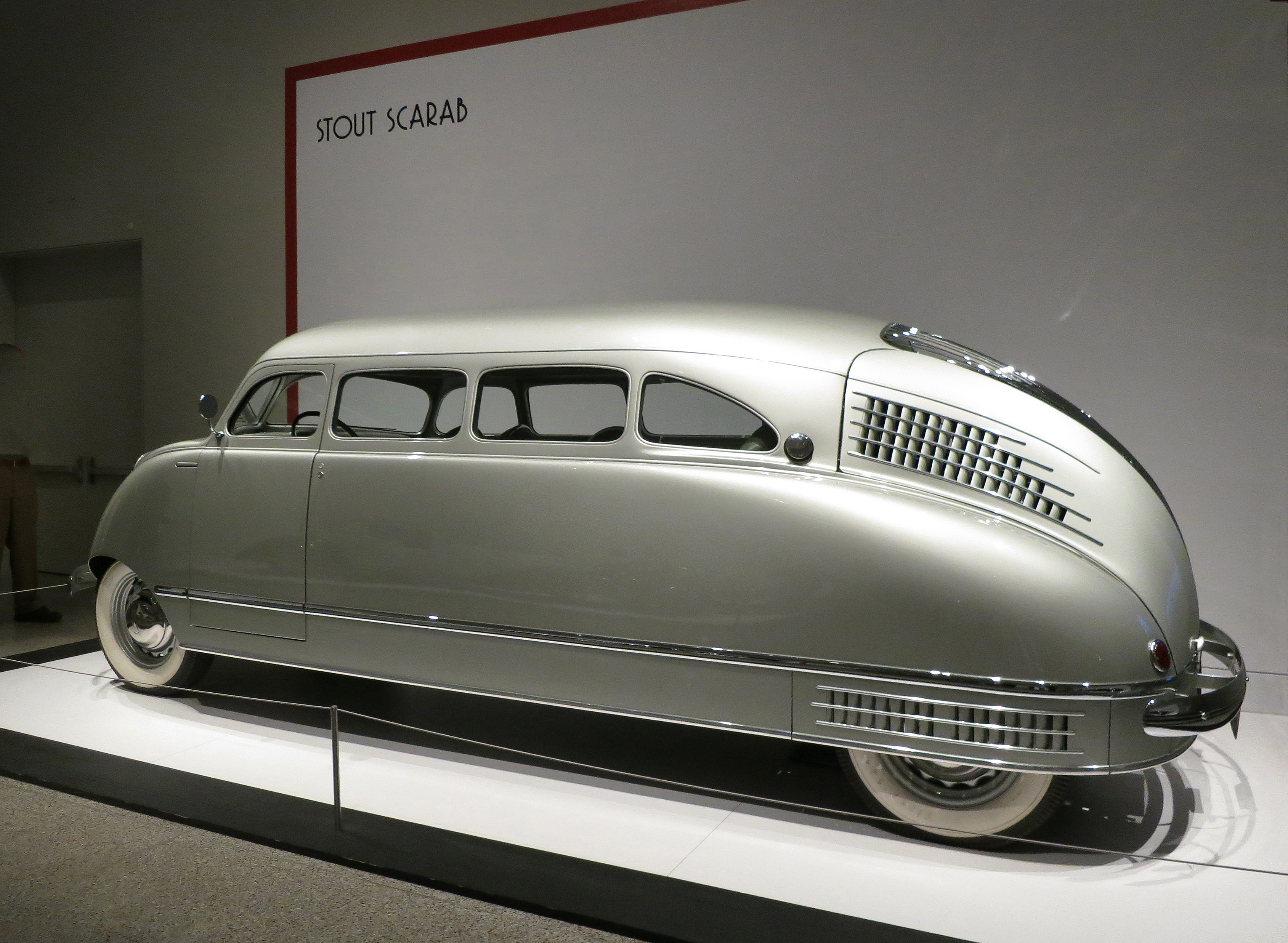

The Stout Scarab

No list of amazing '30s concepts would be complete without the ultimate in art deco design and arguably one of the first Minivans ever conceived: The Stout Scarab.

William B. Stout is consider the "father of modern aviation," according to Hagerty. His Stout airline, the first with a set schedule, would eventually become a little company called United Airline. He eventually wanted to try his hand at more innovative mechanical design and so came up with the innovative Scarab:

"The driver will have infinitely better vision from all angles," Stout wrote in the Scientific American in 1935. "The automobile will be lighter and more efficient and yet safer, the ride will be easier, and the body will be more roomy without sacrificing maneuverability."

Inside, only the driver's seat was fixed. The others could be turned up to 180 degrees to face each other, and there was a fold-down table for meals or to play games. The cabin also offered cutting-edge amenities like a dust filter to enhance the inside air, interior lighting, thermostat-controlled heat, and power door locks. Only the driver's door was located in its conventional place; passengers entered and exited through a central, push-button passenger door. The ceiling was covered in wicker-looking lacewood, front to back.

Stout thought he had a real winner on his hands. But with the Great Depression, few could afford the $5,000 asking price (some $100,000 in today's money.) In the end, only nine cars were built and all of them went to members of the board for Stout Motors. Only five remain today.