The 20 Weirdest Indianapolis 500 Traditions And Superstitions Explained

With 106 years of tradition under its belt, the Indy 500 can seem a little mysterious to new fans

With this year signaling the 106th running of the iconic Indianapolis 500, it would be more than fair to say the race has had a chance to accumulate its fair share of traditions and superstitions along the way. Some of these traditions might seem totally strange to new fans — but we here at Jalopnik are here to break down 20 of the strangest Indy 500 traditions so you can better appreciate some of the weirder aspects of the race.

Why Do They Drink Milk?

After he took the checkered flag, 1933 and 1936 Indy 500 winner Louis Meyer climbed out of his car and asked for one thing: a cold glass of buttermilk. Legend has it that his mother told him to drink it on hot days, so Meyer went ahead and did it. A few drivers followed suit in the aftermath, but shortages during World War II saw the milk soon replaced by water.

The tradition of winners regularly drinking milk was revived in the mid-1950s, when milk companies started sponsoring the event — if you sip milk in Victory Lane, you'll receive a handsome $10,000 award. And with the American Dairy Association sponsoring the event, you have to drink some form of dairy milk. Sorry to those of you who are lactose intolerant!

The milk thing is serious. I'll never forget arriving at the track bright and early for my first Indy 500 and watching a man walk through the Pagoda Plaza with a suitcase handcuffed to his wrist. When I asked someone what was inside, I was expecting it to be a cash prize. No — it was the bottles of milk, primed and ready for the winner to drink.

Don't believe that it's a Thing? In 1993, Emerson Fittipaldi decided to sip some orange juice instead of milk since he, y'know, owned citrus farms and wanted to promote his business. Fans weren't having it, and he was heavily booed at subsequent race weekends. Folks in Indiana still hold a grudge.

What Does “Carb Day” Mean?

While most folks at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway will be imbibing plenty of carbs in the form of beer, Carb Day isn't actually about those carbs. Formerly called Carburetion Day, it was the name for the final practice session on the Friday before the Indy 500, when drivers and teams would tune their carburetors based on race day conditions.

Indy 500 cars haven't featured a carburetor since 1963, but tradition dictated that the name stick. Now, Carb Day features practice, a pit stop competition, and plenty of concerts.

Why Isn’t This a Normal Race Weekend?

Most modern race weekends are composed of three days. On Friday, there's practice; Saturday is qualifying; Sunday is the race. Instead, the Indy 500 features several days of mid-week practice leading up to two days of qualifying during the weekend before the race. Why?

Well, starting with the first-ever Indy 500 in 1911, practice for the race opened on May 1. Not every team was out there with a car on track at that time, but there were plenty of local outfits that would set up shop in the Speedway as early as mid-April. That's why people refer to the weeks leading up to the Indy 500 as the "Month of May." It quite literally used to be a full month of track time.

1974's energy crisis, though, saw the May schedule reduced. It was well-received by fans, drivers, and teams, so the shortened schedule has remained. This year, the Month of May has included a race on the IMS road course, four days of practice leading up to two days of qualifying, plus one day of practice and one Carb Day session leading up to the race.

Are Those Bagpipes?

The Indianapolis Gordon Pipers are a staple of both the Indy 500 and Colts games in the area — but it can be a little surprising to see a group of bagpipers walking through the track on race day morning. A group of volunteers, the Gordon Pipers have been performing at the 500 since 1962. You'll see them at the 500 Festival Parade, during pre-race ceremonies (they often lead the Borg-Warner trophy into the track), and while the winner heads to victory lane.

Why “Back Home Again in Indiana?”

"Back Home Again in Indiana," one of the best-known songs about the state, has been performed before the race every year since 1946, and it immediately precedes the command for drivers to start their engines. Because of that, many longtime Indy 500 fans get chills each time they hear it.

The most notable performer of the song is undoubtedly Jim Nabors, who led fans into the Indy 500 between 1972 and 2014 — though there are some reports that it was played as far back as 1919 to celebrate the event.

Since Nabors' retirement from singing, Jim Cornelison — singer for the Chicago Blackhawks — has taken up the mantle.

That Is a Massive Trophy

An iconic race deserves an iconic trophy, and the Borg-Warner is just that. First introduced in 1936 by automotive supplier BorgWarner, the trophy is something of a Speedway relic. While it's awarded to every single Indy 500 winner in Victory Circle, it resides in the IMS Museum for the rest of the year. Winners are instead given a replica of the trophy, affectionately known as the Baby Borg.

This trophy is massive. It clocks in at 5'4" and weighs almost 153 pounds. Because it became tradition to add a bas-relief of the winning driver on the trophy, a large base was added in 1986 and subsequently replaced with an even larger base in 2004.

Fun fact: You'll usually see the Borg-Warner photographed from a few specific angles. That's because the little man with the flag on the top of the trophy is naked, and his penis is out:

so here's a fun fact for all my new Indy 500 friends:

the massive Borg-Warner trophy is generally photographed from the same angle for a reason. that reason is because the little man on top is flashing the entire world his peepee pic.twitter.com/vPvxWuR47K

— Elizabeth Blackstock (@eliz_blackstock) May 24, 2022

I appreciate the effort to preserve his modesty, but we will not be doing that here on Jalopnik dot com.

What’s Up with the Yellow Shirts?

As early as 1945, track safety personnel started wearing bright yellow shirts to make sure they were easily visible to fans and drivers. The current yellow short-sleeve t-shirt was first adopted in 1975. Now, members of the safety patrol are simply known as "yellow shirts."

The Yellow Shirts have become an institution in Indy; they're largely volunteers but are paid $8 per hour. I know plenty of Yellow Shirts who volunteer because it's basically a free way to see the race — as long as you're willing to prove that you should be allowed to, say, patrol a grandstand.

Why Do Drivers Still Get a Wreath?

Victory wreaths used to be a big thing in motorsport, and the first wreath awarded to an Indy 500 was made for Jim Rathmann in 1960. They were designed by a florist named Bill Cronin, who had consulted on everything from the Rose Bowl to the Indy 500.

When Cronin died in 1989, the wreath's design remained the same in tribute to him. Now, the victor will don a wreath with 33 ivory cymbidium orchids that feature burgundy tips in honor of all 33 starters for the race. Woven into the wreath are red, white, and blue ribbons and tiny checkered flags.

Is That Really the Drivers’ Meeting?

On the Saturday of the Indy 500 weekend, all 33 drivers starting the race are presented with their starter's ring, along with several other awards, in a totally public forum that fans can watch. This is called the drivers' meeting, and when I attended my first Indy 500, I was kind of surprised; aside from general rules, it didn't really seem like a proper drivers' meeting.

That's because it's not. It's just a ceremonial meeting, while the actual meeting takes place on the morning of the race. The public drivers' meeting is a way to get fans involved in the pre-race action.

Saturday has also become a day of autographs and fan festivals, so make sure to get to the track early.

What’s the 500 Festival?

In 1957, longtime fans of the Indy 500 founded the 500 Festival, a non-profit organization that promotes the Indy 500 leading up to the race. There are dinners, races, and more, but the organization is best known for the 500 Festival Parade, which takes place on the Saturday before the race. The parade features all 33 drivers, including some celebrity grand marshals, floats for local businesses, and marching bands.

Why Is it Called the Brickyard?

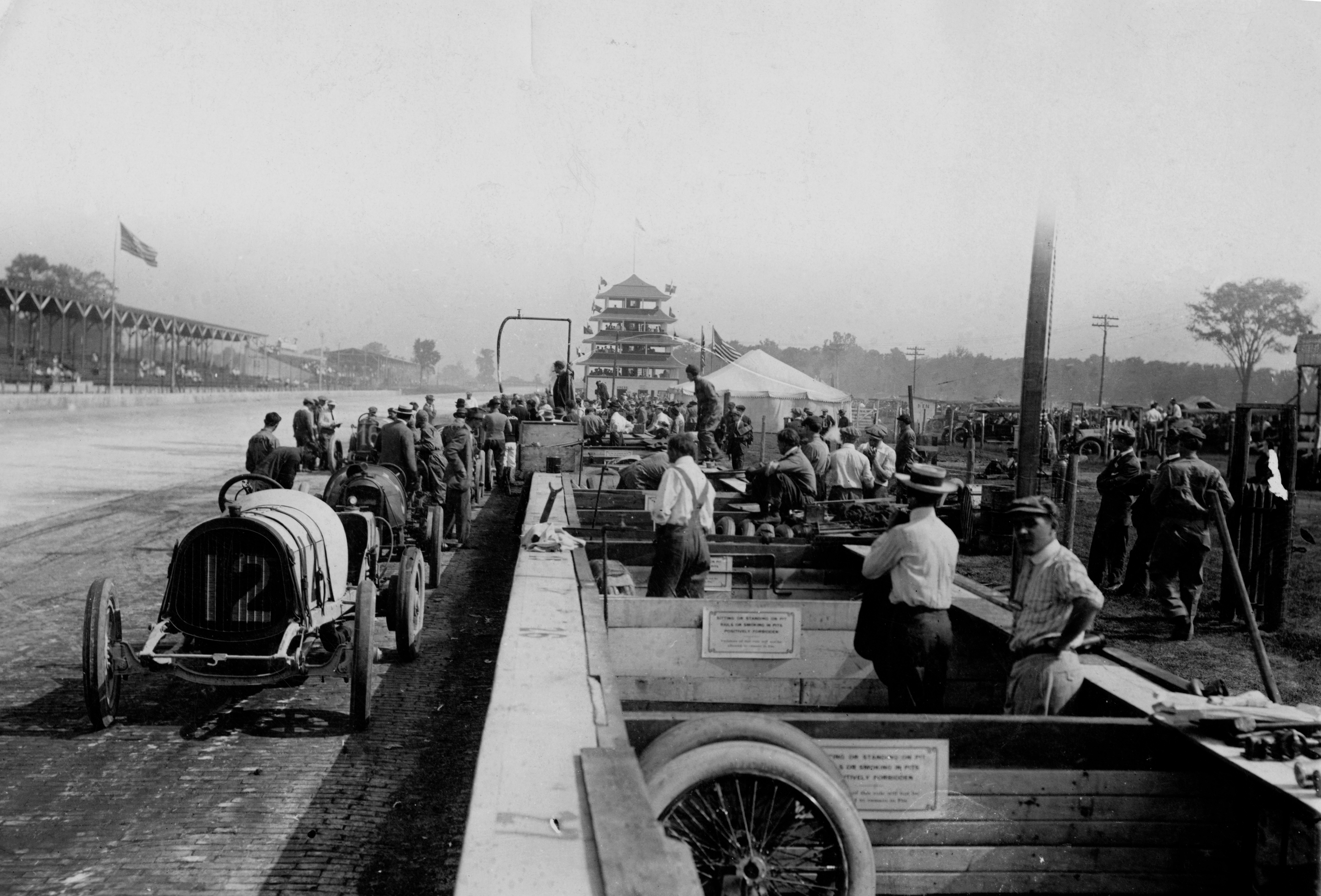

When the Indianapolis Motor Speedway track surface was originally laid in 1909, it was covered in a mix of crushed stone and tar that proved to be totally unsuitable for racing. To prepare for the mounting importance of the 500-mile race, the surface was quickly paved over in brick.

If you think brick is a strange surface for racing, you're correct, and track management realized that by the 1930s, when they started paving over the brick with asphalt, one piece of the track at a time.

The full circuit was fully paved over after the 1961 event, with one exception: One yard of bricks was left exposed at the start/finish line to preserve some of the circuit history. Those bricks remain today.

What’s Gasoline Alley?

No one is quite sure where the name "Gasoline Alley" came from, but it has been a way people referred to the garage area of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway for decades. Some sources say the name comes from a comic strip also called Gasoline Alley, but the exact origin is likely lost to time — and the name has stuck despite the fact that IndyCar phased out gasoline in the mid 1960s.

The Andretti Curse

The Andretti family is something of a dynasty at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway — but not because they've had any success. After Mario Andretti's 1969 victory, four other Andrettis have competed in the race, but none of them have won.

According to IndyCar reporter Robin Miller, the bad luck was reportedly the result of a hex. Andretti won his only 500 behind the wheel of a car owned by Andy Granatelli and Clint Brawner — but the following year, Granatelli and Brawner started feuding over ownership of the team and parted ways; Andretti stuck with Granatelli, leaving Brawner out in the cold. Brawner's wife Kay allegedly placed a curse on the Andretti family, vowing that no Andretti would ever win another 500.

Whether you believe Miller's colorful yarn or not, it is a bit curious that Andrettis could perform so well at the Speedway... except on the lap where it counted most.

Curse of the Smiths

Almost 800 drivers have started the Indy 500 in its century of existence, but not a single one of them has had the surname "Smith." It's especially strange, since Smith is the most common surname in the United States. The closest we've ever gotten is with Sam Schmidt, whose surname is a German-language translation of "Smith."

Green, Rabbits, and Number 13

With such a long history, certain superstitions have risen, such as:

-

Number 13: The number 13 is generally considered bad luck, but that was compounded in the first Indy 500 with the No. 13 car failed to make the race. The number was then actively disallowed between 1926 and 2002. Since then, only three drivers have used the number: Greg Ray, E. J. Viso, and Danica Patrick. (Neither Viso nor Patrick finished the race).

-

Green: Despite the fact that two winning cars have been green, the color has been considered bad luck by many drivers, and some teams would even go so far as to disallow the use of green sponsor logos during the race weekend.

-

Peanuts: There's been a longstanding rumor lingering in the Speedway since the 1940s that says a crashed car was found with peanuts in the cockpit. There's never been confirmation of this, but peanuts were banned from the track until 2009.

-

Rabbits: Finally, a sign of good luck! Because the Indy 500 was the only race hosted by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway for eight decades, the track's surroundings played host to all kinds of wildlife. Seeing a rabbit was considered good luck for drivers.

Why Are There 33 Drivers?

The Indy 500 starting grid is limited to a field of 33 cars, or 11 rows of three cars. But there is a reason — and we've written about it before here on Jalopnik.

To put it quite simply, interest for the inaugural 1911 Indy 500 was extremely high, and 40 cars were entered in the race. At the time, the event was sanctioned by the AAA, and its Contest Board though that 40 cars might be a few too many.

The AAA decided that each car should have 400 feet of track to itself in order to preserve safety by preventing crowding. On a 2.5-mile oval, that meant a maximum of 33 cars could start the race.

Not every race has included 33 cars, though. The Speedway's first president limited entrants to 30, and the Great Depression years actually saw over 40 cars compete.

That’s a Long Pre-Race Ceremony

The Indy 500 isn't just a race, it's a daylong event. Hardcore fans line up for the dropping of an aerial bomb at 5 or 6 a.m. that signals the opening of the gate, and from that point on, they'll be greeted with marching bands, music, driver introductions, parade laps, and more.

Basically, the slow crawl of time means that the Indy 500 has accumulated a ton of pre-race traditions throughout the years, and if there's one thing Indy 500 fans love, it's tradition. So, while the pre-race buildup might seem excessive to an outsider, each moment is a warm, fuzzy reminder of Indy 500s past for longtime fans.

Why Memorial Day Weekend?

The decision to race on Memorial Day goes back to the very founding of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In its first year of existence, the track intended to host races on Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, and Labor Day, but low attendance in the second and third races of the year convinced management to consolidate those three races into one long event.

But why Memorial Day? Well, Memorial Day tended to coincide with a break in local farming activities, and the weather was generally cooperative. However, since most farmers worked on the weekends, the race was actually held on Memorial Day proper: May 30. The goal was to host a 500-mile race in the morning, leaving time in the evening for viewers to return home for supper.

When the Uniform Monday Holiday Act was enacted in 1971, Memorial Day was moved to the last Monday in May, and the race moved to the weekend leading into that Monday.

What’s the Last Row Party?

Each year, the Indianapolis Press Club Association hosts an event called the Last Row Party. Part cocktail party and part roast, it's a charitable event that anyone can buy tickets for. The drivers that make up the last row of the grid turn up for interviews and some jokes, and they're awarded 31, 32, or 33 cents, depending on their grid position, and some other goodies like jackets.

The event has run since 1972. The cost of tickets go toward scholarships for aspiring teen journalists.

No Donuts — But Kisses Are OK

It's pretty common for the winners of American motor races to celebrate their win with some donuts on the front stretch of the race track — but that is not kosher in Indianapolis. In fact, it's considered pretty disrespectful, since the front stretch is lined with the aforementioned yard of bricks. Those bricks represent the history of the Speedway, and burning rubber over them is bad form, since it causes unnecessary damage.

In 1996, though, NASCAR Brickyard 400 winner Dale Jarrett chose to celebrate his victory in a new way, one that paid respect to that yard of bricks. In fact, he kneeled down to kiss them. That tradition was picked up by IndyCar drivers in 2003 and has lasted ever since.