Team Lotus' Essex Formula 1 Sponsorship Collapsed In The Wake Of Financial Scandal

David Thieme's Essex Overseas Petroleum company was too good at making money.

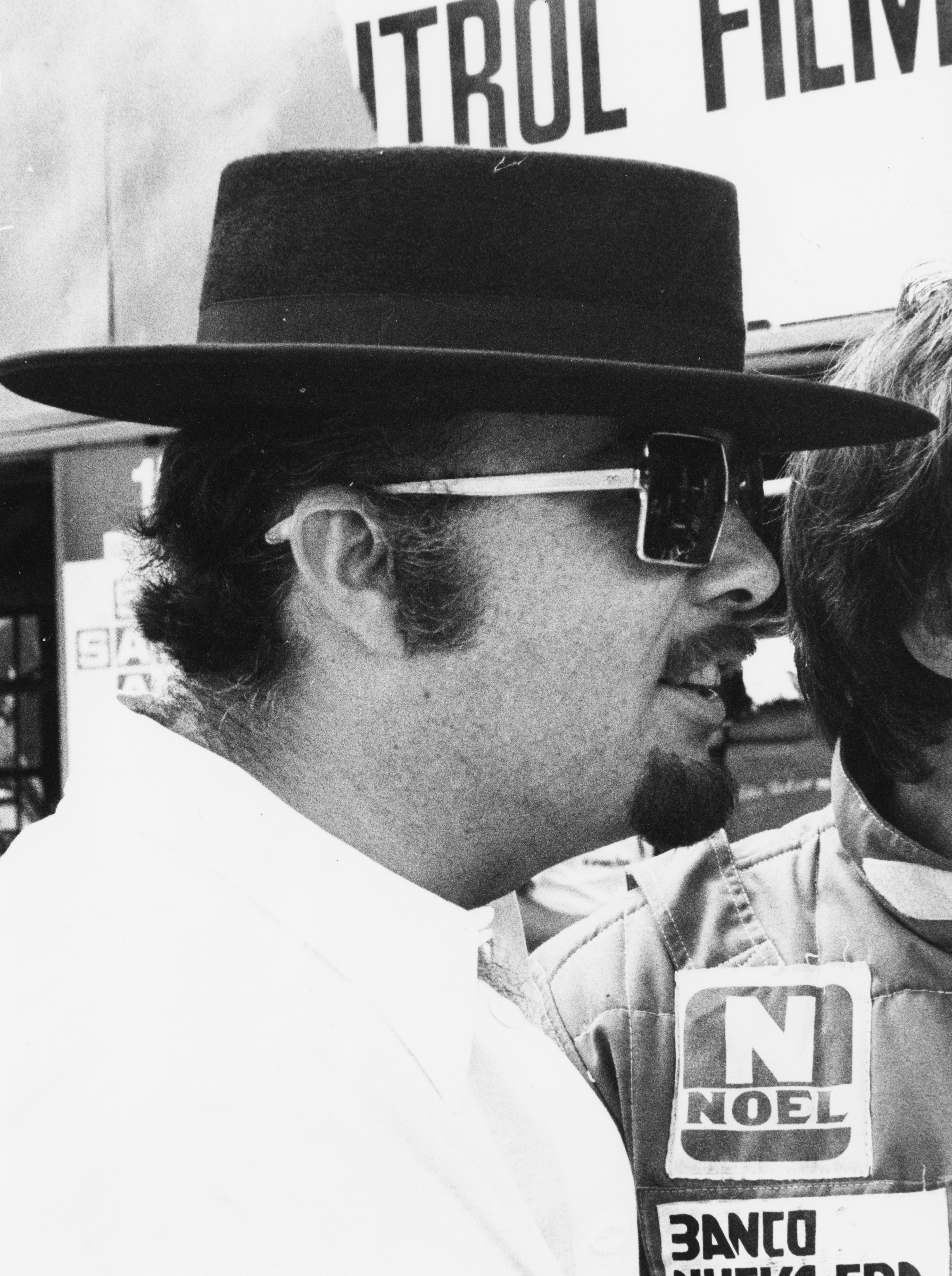

If you were to imagine the consummate playboy of the late 1970s and early 1980s, there's a good chance you might picture someone like David Thieme. Show up to any elaborate Team Lotus party during a Formula 1 weekend, and you would inevitably find Thieme holding court with his goatee, black fedora, and square sunglasses. He and his company, Essex Overseas Petroleum Corporation, seemed impossibly good at making money and spending it on racing. And then he was arrested.

(Editor's note: This week marks the release of Racing with Rich Energy: How a Rogue Sponsor Took Formula One for a Ride by Elizabeth Blackstock and Alanis King. To celebrate a book that began as a blog on Jalopnik, co-author Blackstock is covering the history of some of F1's other questionable sponsors. These sponsors are touched on in the book, but not in depth. Racing with Rich Energy is available via McFarland, Amazon, Kindle, and Eurospan for international buyers.)

The Lotus team is one of the most storied in Formula 1 history. Colin Chapman had spent several years perfecting his groundbreaking road cars before he hit the Grand Prix circuit for the first time at Monaco in 1958, and the team's first victory came three years later at the 1961 United States Grand Prix. Of its 489 starts spanning several decades, Lotus took 79 wins, seven Constructors' Championships, and six Drivers' Championships. The team fielded legends like Graham Hill, Jim Clark, Pedro Rodriguez, Jochen Rindt, and Mario Andretti.

It was also the team that effectively invented modern sponsorship as we know it, with Colin Chapman accepting Gold Leaf Tobacco money in exchange for painting his cars in the brand's colors. It was a significant departure from the past, where cars were painted a specific shade to represent a country. It enabled teams to operate on larger budgets — but it also created the potential for sponsorship money to come from questionable places.

One of those places was Essex Overseas Petroleum Corporation, owned by American designer David Thieme.

Thieme had made his fortune first from his own design firm when he took on ownership of oil trading company Essex Overseas Petroleum Corporation. Essentially, Thieme took advantage of political instability in the Middle East by buying oil when demand was low and selling it at a huge mark-up when countries started battling. In 1977, he even managed to nab some extra money from Credit Suisse to make larger trades and, in turn, make more money.

As part of an oil company, Thieme had been involved in the development of certain cars and jets, which gave him his introduction to the racing world. With former driver turned sponsorship guru François Mazet, Thieme struck up a friendship with the legendary Colin Chapman in the late 1970s. By the end of April in 1979, Essex logos adorned Team Lotus' cars — and Thieme was so inspired that he also sponsored Porsche factory entries at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

What started out as a sponsorship quickly became more. From the Colin Chapman Museum:

In December 1979 he launched Essex Team Lotus at the Paradis du Latin cabaret in Paris, with feather-clad dancers and a Lotus in Essex colours descending from the roof, with Mario Andretti, clad in a dinner jacket, descending with it. In 1980 Thieme took the title sponsorship of Team Lotus, with a flashy new red, blue and silver livery for Andretti, Elio de Angelis and later Nigel Mansell. Everything that Thieme did was extravagant, with the 1981 launch at the Royal Albert Hall, with 900 guests and his double-decker hospitality bus parked outside with Thieme's helicopter (in Essex colours, of course) on top. Ray Charles and Barbara Dickson sang for the guests (including Margaret Thatcher) and an Essex-liveried Lotus Esprit was raffled and much Dom Perignon was drunk. The 1981 season proved to be difficult with the twin-chassised Lotus 88 causing controversy when it was introduced in Long Beach.

Thieme wasn't afraid to spare any expense. Journalist Maurice Hamilton remembers Thieme hiring Michelin-starred chef Roger Vergé to cook for Lotus in the team motorhome and hearing rumors that Thieme hired his own 747 specifically to fly in enough bougainvillea for one party to make it feel like the venue was in the French Riviera.

While few would turn down a party, Thieme's money also helped out with the massive expenses that came with building a new car — in this case, the legendary Lotus 88.

This specific vehicle was made entirely of carbon fiber and introduced a groundbreaking "twin chassis" technology. After the FIA banned moveable skirts, which teams used to generate greater downforce in the ground effect era, some teams began looking into ways to circumvent the rules with hydropneumatic suspension. Essentially, when stationary, those vehicles seemed to comply with ride-height regulations — but get them moving on track, and the suspension enabled the car to suck right down to the ground. It was uncomfortable for drivers, but the pace it created was immense.

Alongside designers Peter Wright and Tony Rudd, Chapman transformed the former Lotus 86 into the Lotus 88, which featured two chassis, one inside the other. The inner chassis contained the driver's cockpit and was independently sprung, so the driver wouldn't feel the buffeting impact of ground effect. That meant the outer chassis could totally get rid of its wings, since it essentially became one large ground effect system that created obscene amounts of downforce.

The FIA quickly banned the car, which Chapman argued was totally legal — but that wasn't the only problem to take place in 1981.

On April 14, 1981, UPI reported that Thieme was arrested upon arriving at the Kloten airport in Zurich, Switzerland on allegations of fraud. According to Credit Suisse, he had fraudulently acquired $7.6 million of the bank's money, which resulted in many of Thieme's belongings being impounded. After spending two weeks in jail, he was released on $150,000 bail thanks to Saudi Arabian businessman and Williams sponsor Mansour Ojjeh and subsequently disappeared. With him fell the Essex empire.

Thieme had joined up with the Lotus team just after it secured the Constructors' Championship in 1978, and he was rewarded with a handful of podiums during his time as team sponsor — but the ever-evolving technology of the early 1980s left the team with a string of retirements and only a handful of points-paying finishes during Thieme's tenure. Winning, though, seemed to mean less to Thieme than did the act of being seen flaunting his wealth at the race track.

The arrest, too, coincided with the banning of the Lotus 88. In The Tuscaloosa News, Chapman responded to a question about whether or not he'd pull out of racing with, "I have to. I haven't got any cars now and I don't know about my sponsorship."

The team did manage to finish the year with a seventh place overall in the 1981 Constructors' Championship.

Lotus didn't fold in the immediate wake of Thieme's arrest; instead, Colin Chapman's death in 1982 preceded a period of chaos that was eventually resolved as the team hired a slew of new visionaries to design its cars. By 1984, Lotus was regularly performing well, and with Ayrton Senna as part of the team, the crew secured seven wins in three years between 1985 and the conclusion of the 1987 season.

Unfortunately for the team, though, Lotus began to decline soon after, and as the 1990s kicked off, it was a rare sight to see a Lotus machine in the points. Its final points were scored at the 1993 Belgian Grand Prix, and, at the conclusion of the year, finances were so tight that there wasn't enough money left over to to develop a new machine for 1994. The team struggled on with old machinery until the fifth race of the season, but soon after, Lotus applied for an Administration Order that would protect it from creditors.

Before the end of the year, the team had been sold off to David Hunt, brother of 1976 World Champion James Hunt, but development of the car stopped by the start of the 1995 season. Lotus' last race was the 1994 Australian Grand Prix.

Was the team's decline directly caused by David Thieme? It would be very hard to make a compelling argument in that regard. Instead, though, Thieme's fall from financial grace did likely contribute to Lotus' eventual dissolution, as it was one in a series of unrelated events that took place in the early 1980s that ultimately changed the direction of Lotus. Without Thieme's presence, it's entirely likely Lotus could have folded, anyway. But as we've seen time and again, the very fact that a team falls victim to a fast-talking moneyman has only been a black mark in its history.