Still Waiting For A Savior: Before GM Left, Avanti Sold An Ohio Town An Impossible Dream

When the first Avanti finished in Youngstown, Ohio, rolled off the line on Sept. 30, 1987, it was touted as a rebirth for both a once-revolutionary car and for a region ravaged by the closure of its steel mills.

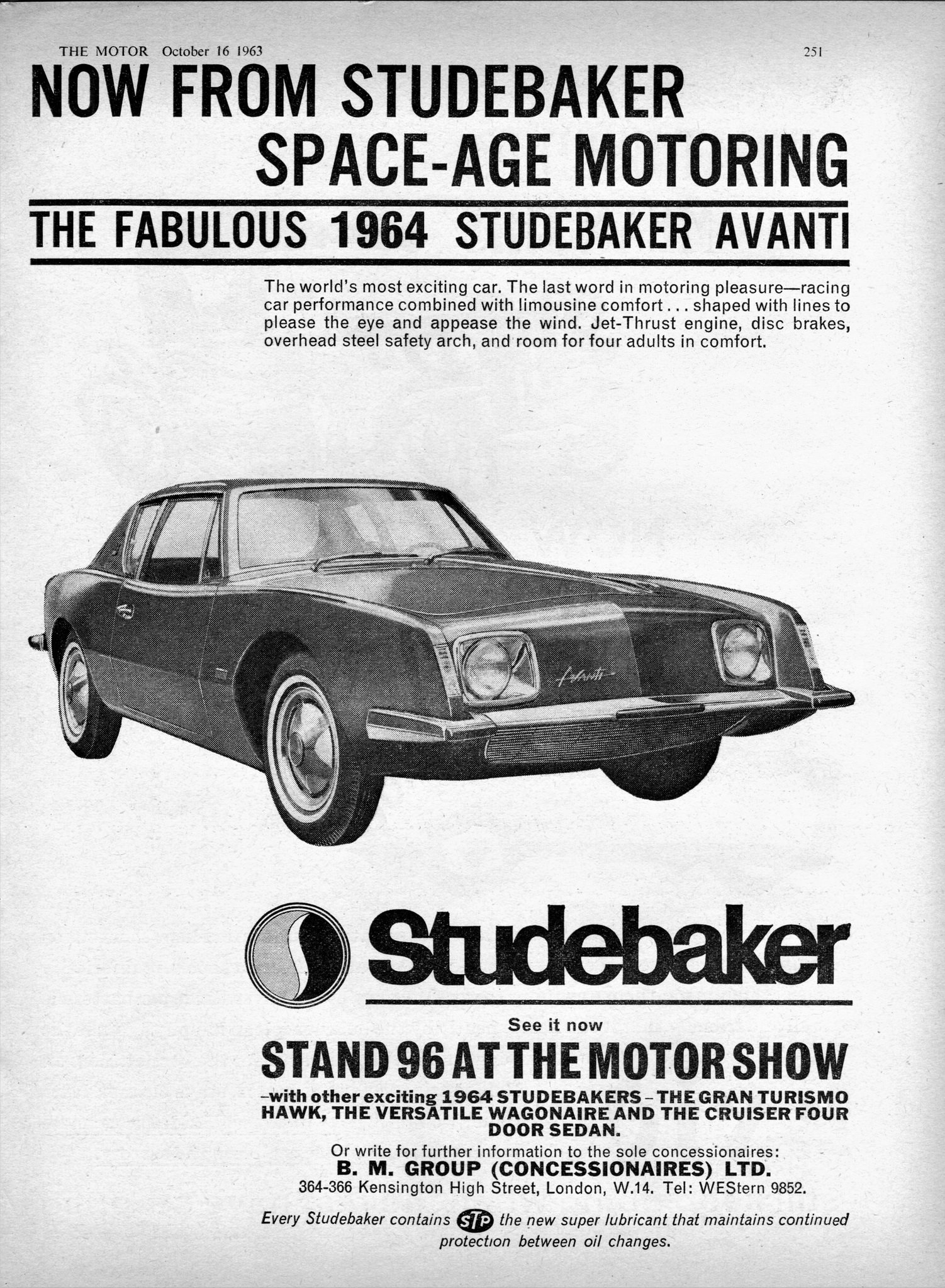

Introduced two decades earlier as Studebaker's last gasp, the Avanti wasn't enough to save the venerable automaker in the 1960s, but the unique vehicle acquired a cult following and lived on in limited numbers.

The company changed hands a couple times and filed bankruptcy before finding a pair of advocates in Michael Kelly, an auto industry executive whose "Midas touch" belied a checkered past, and J.J. Cafaro, the flamboyant, workaholic scion of a Youngstown family that had grown from humble origins to one of the largest commercial real estate developers in the country. Both men, later in life, would face convictions for financial wrongdoing.

But earlier in 1987, Kelly was looking for more space to expand Avanti's line, made in Studebaker's old factory in South Bend, Indiana. He found Cafaro and Youngstown, an area with a tradition of making things, on the prowl for something—anything—to try to compensate for the sudden loss of thousands of steelmaking jobs that sent the Ohio economy into a tailspin a decade earlier.

"At that time it was a fantasy," Kelly was quoted as saying in the Youngstown Vindicator newspaper, as the gunmetal gray convertible rolled off the assembly line in a building once home to one of the steel mills that were so vital to the Mahoning Valley's economic well being. "I'm glad to say it's a dream come true."

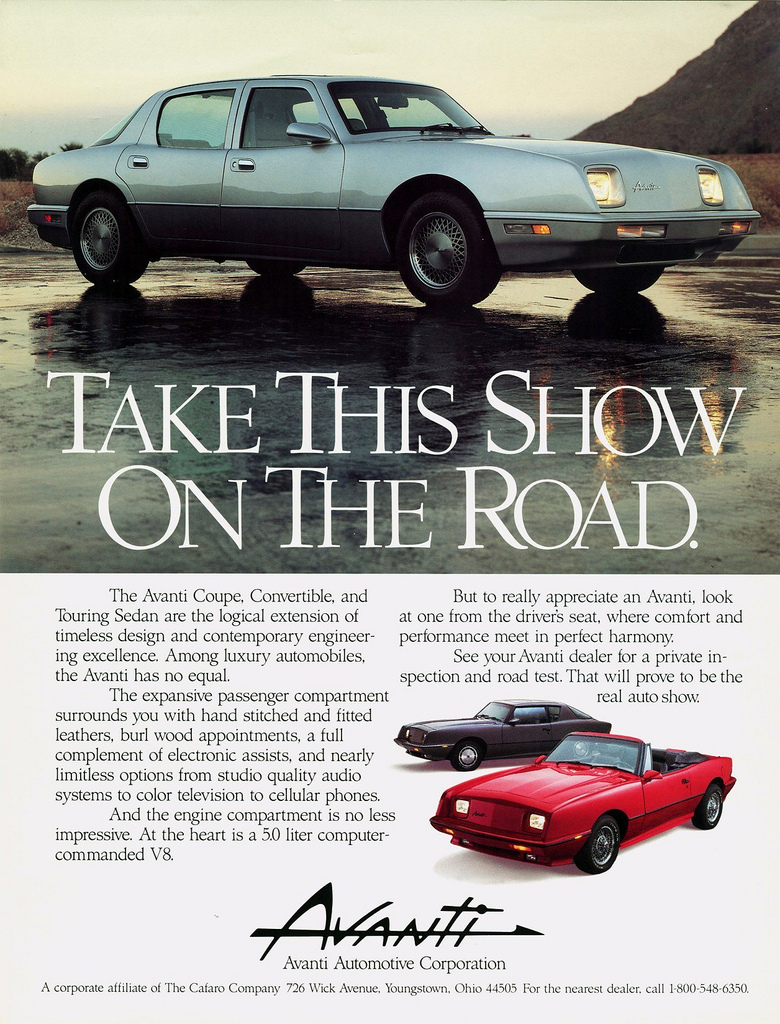

Kelly and Cafaro's big plans for Avanti included new models, like a sedan and a limousine in addition to the convertible and coupe. Soon, Kelly and Cafaro promised, hundreds of people would be working there. Ads were bought. A character on the TV show Dallas drove an Avanti, and one of the cars would be given away on Wheel of Fortune.

But the resurgence was not to be. Within a year, Kelly would be out at Avanti. He had made his money. Two years after that, the factory was officially closed. Cafaro lost more than $26 million trying to make a go of Avanti in Youngstown, a place still waiting for its savior.

This week it lost the only one it had left. Although the Mahoning Valley was known through most of the 20th century as a center for steelmaking, its history is interwoven with the American auto industry. The General Motors Chevrolet Cruze plant in nearby Lordstown is ending production this week after GM announced last fall it would be "unallocated"—not "closed," as that would violate its union contract.

The GM Lordstown plant opened in 1966, when the steel mills were still running full tilt, and after the mills started closing a decade later, has been one of the last remnants to the region's industrial past and prosperity.

The area had long bet on GM, but by the end of this month, according to reports, 1,700 full-time workers will be out of jobs. The last 40 years have been bleak in the Mahoning Valley, and GM Lordstown's closure is making things a little bleaker.

But there was another time the Mahoning Valley rested its fortunes on an automaker and got bit, when two entrepreneurs sold the area on bringing a 25-year-old car back from the grave.

When Kelly bought Avanti from bankruptcy in 1986, it had already acquired a reputation as "the car that wouldn't die."

It was the last collaboration between Studebaker, a company that got its start building covered wagons in the days before the Civil War, and Raymond Loewy, a French native who'd become one of the pre-eminent industrial designers in the world.

Even as a soldier in the French Army in World War I, Loewy had a sense of flair, tailoring his uniform pants so they looked better on him. After the war, he came to America. He worked briefly as a window dresser for Macy's—he was fired after one day, he wrote in his autobiography, because his style didn't mesh with his supervisor's—and was an artist for advertisements before branching into the field of industrial design.

His work is familiar to most consumers even if his name isn't. He redesigned the pack for Lucky Strike cigarettes, changing the color from green to white (leading to the famous ad campaign during World War II, "Lucky Strike Green has gone to war!") The Air Force One jet still bears the livery he designed for John F. Kennedy. Exxon, Shell and BP stations bear logos that were his design as well. He helped Coca-Cola redesign many products and craft its modern look, and was responsible and many other things, from household appliances to railroad locomotives.

Of course, he also designed cars. His first relationship in the auto industry was with Hupmobile in the early 1930s. Foreshadowing his relationship with Studebaker, it was a car manufacturer throwing elbows to try to stay relevant in the market. His designs were too bold for them, but he found a longer-lasting and more productive relationship with Studebaker.

Loewy first designed Studebakers for the 1938 model year. By that time, the automaker had weathered the Great Depression—although not before going into receivership in 1933—but the end of World War II brought new challenges, as the company was one of the last independent automakers in the United States (its location away from Detroit, in South Bend, Indiana, was probably no help).

Studebaker was the first American manufacturer to come out with new models after the war, in 1947. They were designed by Loewy's team too. His designs for the 1953 coupes celebrating the company's centennial, now informally referred to as "Loewy coupes," were heralded as works of art.

But Studebaker was limping along through the 1950s, and when his contract was up in 1957, it wasn't renewed, as a cost-saving measure.

In 1954, Studebaker was bought by another now-vanished American manufacturer, the luxury automaker Packard. It was supposed to be a win-win. Packard would benefit from Studebaker's larger dealership network, and Studebaker would get a badly-needed infusion of cash.

It turned out to be a disaster. The debts were too much to handle, and Packard's auto plant in Detroit shut down in 1956, with production moving to Studebaker's factory in South Bend, Indiana. The name survived for two more years, but the cars, little more than Studebakers with a Packard insignia, were derided as "Packardbakers."

In 1961, Sherwood Egbert, a California native with no automotive background, was named president of the company. Egbert perused auto magazines while flying back and forth between California and Studebaker's headquarters in South Bend, and hit on an idea of a new car to get away from Studebaker's moribund image. He enlisted Loewy's help in making it a reality.

"Raymond, I want you to do it at once," Loewy recalled Egbert telling him, in a 1984 story in Collectible Automobile magazine. "And it must be an absolute knockout."

Egbert initially envisioned a two-seat roadster, but the new model, built on Studebaker's Lark platform, would be a personal luxury car, a growing segment of auto sales in the early 1960s. It was suggested that the car would carry a revived Packard name, or possibly Pierce-Arrow (which had been owned by Studebaker briefly in the 1930s), but it was ultimately called "Avanti," from the Italian word for "forward," and Egbert wanted it in a year, no small feat when the lead time for new cars is usually several years.

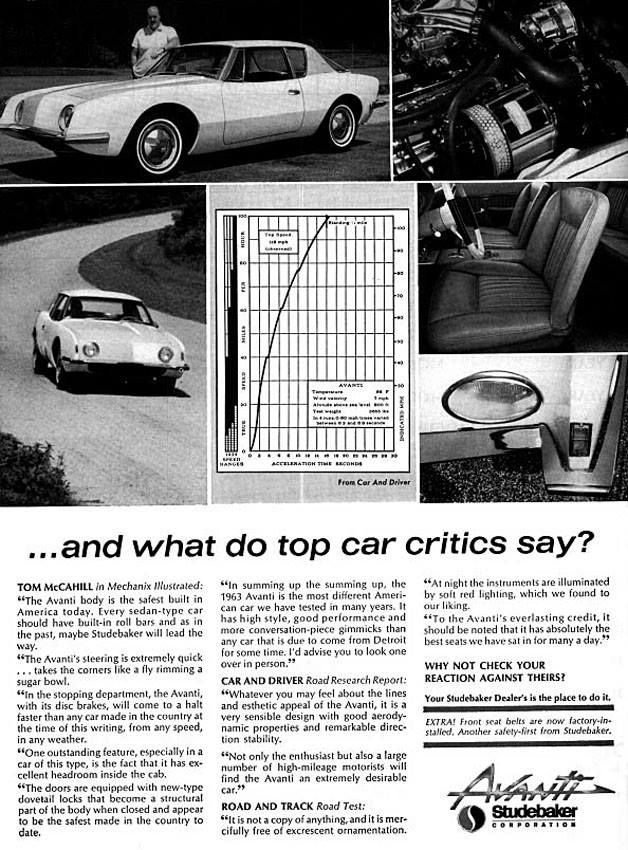

The car made its debut at the 1962 New York Auto Show, and it was like nothing that had ever been seen before. The coupe had a fiberglass body (by necessity; a steel body would require expensive and time-consuming retooling) but no grille, very little chrome and no fins in an era when they were omnipresent.

"The Avanti has created a new class of American automobile," Egbert said in promotional literature. "It is a car of sophisticated design and great elegance. To this it adds the advantage of high performance with unusual safety."

Beyond its looks, it was technologically advanced in its time as well. The car had disc brakes, a built-in roll bar, and years before the Nader pin became a standard safety feature, the Avanti had one, to secure what were touted as the biggest doors on any production auto.

"Its handling ability compares with the very best I have ever driven," said auto racer Andy Granatelli, who test-drove the Avanti, in a news release distributed by Studebaker at the Avanti's release. (It's worth noting that Granatelli's Paxton Products was a subsidiary of Studebaker by then.) "It certainly out-handles all other American built automobiles with no exception."

Studebaker made 4,643 Avantis, but the car's creature comforts and handling weren't enough to save the company, which closed its South Bend factory in 1963 (the same year Egbert, ill with cancer, resigned; he died six years later) and retained a Canadian presence until 1965.

Nathan Altman and Leo Newman, a pair of Packard dealers who started selling Studebaker after the merger, bought Studebaker's buildings, dies, blueprints and parts. They wanted to save the Avanti.

"We thought the Avanti was a car years ahead of its time," Altman said.

Altman first went to every automaker in Detroit and they all turned him down. Then Altman and Newman started to build the cars themselves. The car was redesigned slightly (almost imperceptibly) and now used a Corvette engine.

Avanti positioned itself as an American Rolls-Royce, handbuilt and sold in low numbers, fewer than 300 per year. Altman died in 1976, and his brother sold the company to Stephen Blake, who had been fascinated by the car since buying one in 1972.

"I still think it is one of the best-looking cars in the world," Blake said in a Forbes interview in 1989, four years before his death from cancer. "But I bought a mom-and-pop company that was building a 20-year-old car on a 40-year-old chassis with 70-year-old workers in a 100-year-old plant."

Production nearly doubled under the watch of Blake, a real estate salesman and consultant in Washington D.C., and a convertible was introduced. But quality control issues plagued the company, and Avanti was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1985.

The company would soon find a pair of unlikely saviors.

Like most cities in the Great Lakes region, Youngstown had dabbled in the auto industry in its early days, as cars like the Fredonia, Glenwood, Mahoning and Wick all flowered into existence in the first decade of the 20th century and then promptly died. When motoring got started in earnest, seemingly everyone wanted in for a bit. But then as now, making cars is hard, and most of these early companies failed or were absorbed into larger conglomerates.

The most famous automobile with roots in the Mahoning Valley, ironically, was Studebaker's future partner Packard. James Packard had bought a Winton in Cleveland and was unsatisfied with the quality of the car. An engineer by trade, Packard corresponded regularly with Winton, and finally, fed up, the manufacturer effectively told Packard if he could make a better car, then he should do so. Packard started a factory in 1899, and four years later, the company moved to Detroit, which was quickly becoming the hub for American auto manufacturing.

Packard's other concern was an electric company he'd started with his brother in 1890. That company, ultimately employing thousands in the Mahoning Valley, was sold to General Motors in 1932. The General Motors presence in the area grew in 1966 with the opening of a new plant on farmland in Lordstown, roughly halfway between Youngstown and Warren.

The valley's major industry for most of the 20th century was steel. A year after James Packard made his first car in Warren, the Youngstown Iron Sheet and Tube Company was incorporated. The word iron was dropped from its name shortly thereafter, and Sheet & Tube became one of the largest steel producers in the country and, for a brief time in the 1920s, the largest corporation in Ohio. Additional mills for U.S. Steel and Republic Steel could also be found in the Mahoning Valley, leading to the narrator of a 1940s film produced by the U.S. Office of War Information to intone, "In Youngstown we make steel. We make steel and talk steel..."

Those mills required thousands of laborers, one of whom was William Cafaro, who lived not far from the Truscon Steel mill where he worked on the city's east side. Cafaro started the Ritz Bar, also on the city's east side, that quickly became a dining and entertainment destination. From there, he branched out into real estate development, becoming one of the richest men in the country by developing grocery stores and later shopping malls.

In the postwar era, the Mahoning Valley continued to boom. Youngstown Sheet and Tube opened its new headquarters in 1957 — in the suburb of Boardman, mirroring the movement of residents from Youngstown to its surrounding communities. The mills ran three shifts, and the unionized jobs led to one of the highest standards of living in the country, including a home ownership rate that outpaced the national average. But all was not well. The mills dated back to the turn of the century and were outdated technology, and a national steel strike in 1959 opened the door for imported products — made quicker and more efficiently by using the latest technology.

By the 1970s, the auto industry played a major role in the local economy, with more than 50,000 direct or indirect employees. And every one of those jobs would soon be vital to the area's health. In 1977, Youngstown Sheet & Tube, which had been bought by an out-of-town corporation eight years earlier, announced it would close one of its mills a week later, throwing 9,000 people out of work. It was estimated that the loss of Sheet & Tube and deindustrialization in general put more than 50,000 people out of work in the Mahoning Valley.

"Every time politicians came to town, they wanted to use the mills as a backdrop to begin their campaign," said Pat Ungaro, who served on Youngstown City Council before becoming mayor in 1984. "They wanted to show everything that had gone wrong. I got disgusted."

Ungaro said the city was forced to take on the most aggressive economic development plan outside of Hong Kong, and that led to them occasionally getting burned. But when Kelly said he was looking for a second site to produce the cars, Ungaro felt obligated to at least check out the possibility, and he and a contingent of Youngstown city government officials – and Cafaro – to South Bend in April 1987 to plead their case to Kelly.

"We're going to offer everything we can offer to make this thing go," Ungaro said.

When Kelly bought the company out of bankruptcy in 1986 for $722,000, he told the Detroit News, "As a worse case, I can sell off my assets in two years and double my investment."

But Kelly appeared to love the Avanti too much to do that. He grew up in South Bend, and was just entering his teenage years as the Avanti debuted. Kelly, touted in the Youngstown Vindicator as "the epitome of the American success story," started work at a body shop, struck out on his own as a customizer and then owned a successful recreational vehicle dealership before branching into the manufacture of ethanol in the days of the 1970s gas crisis.

Initially, Kelly reassured South Bend officials that Avanti production would stay in Indiana, and new models would be built in Youngstown, but in August 1987, it was announced that Avanti was closing up shop in Indiana and moving completely to Youngstown. South Bend Economic Development Director John Hunt said in the Plain Dealer the following year that Kelly set up the city "as a straw man and then knock(ed) him down."

In the spring of 1987, shortly after the deal was announced for Avanti to come to Youngstown, the Cleveland Plain Dealer also wrote stories indicating that all that glittered with Kelly was not gold. His foray into ethanol ended in a morass of lawsuits, broken promises and angry investors in five states. But the city launched its own investigation, and satisfied, it and the state were still willing to make a deal with him in the name of economic development.

The city promised a $300,000 subsidy in addition to help in demolishing buildings on the site of the plant, on property owned by the Cafaro Co. that ironically was the site of the former mill where patriarch Bill worked. The state would offer a $1.5 million loan.

Avanti sold hope to the Mahoning Valley, with Ungaro saying the move into the former steel mill site "was something money can't buy."

The Cafaro Co. would also put $1.5 million of private equity into the company.

"From what we see, the benefits outweigh the risks in this case," said Cathy Ferrari, a spokeswoman for the Ohio Department of Development, which planned to recommend to the state Controlling Board in favor of the $1.5 million state loan.

Kelly relocated to the Youngstown area, buying a mansion that was owned generations earlier by one of the city's captains of industry. Initial plans were to employ about 200 people, but more than 11,000 applied to work at the new factory. Goals were set to increase production from one car daily to two the following year, up to 1,200 per year by 1990, by which time 450 people would be working at the Avanti plant. Plans included expansion to make the chassis in-house, leading to more jobs.

The new cars didn't look different from the 1960s Avantis, but used a modern Chevrolet chassis instead. More models were planned beyond the coupe and convertible. But the sedan, which was supposed to premiere as a 1988 model, was held off continuously.

As it had been during Blake's ownership, quality control was again an issue. A year after the first car rolled off the assembly line, Kelly was gone, bought out of his interest by Cafaro. He was going back to car customization, stretching limousines, and had plans for another sports car based on a prototype built in Brazil.

When asked if he'd realized his "worse-case scenario" and doubled his money, he said he did. When asked if he made more, he was suddenly coy, saying, "Everyone got what they wanted out of the deal. It was an amicable parting." However, he did say without the influx of capital from Cafaro, he would "probably still be at Avanti ... but looking at spinning it off and going on to my next project."

"My expertise is getting a project up and running for the next person," Kelly said in an interview with the Youngstown-Warren Business Journal where he almost gave the game away. "In the meantime, I make money and hopefully they can make theirs."

Cafaro could not make his. The company lost $2.8 million in 1988, and more than $4.2 million in 1989.

The story is a familiar one to anyone who has followed car startups today: excessive overhead and production costs, quality issues, a questionable sales market, a pricing structure not guaranteed to make a profit and overly ambitious plans eventually doomed the enterprise. One of the reasons the Avanti was able to survive throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s was that the car itself was relatively unchanged.

Plans for a convertible, sedan and even a limousine came all at once, and ultimately, sales figures didn't support everything going on. Cafaro eventually realized he was throwing good money after bad, and it was time to close up shop.

From a Chicago Tribune story a few years after:

"What killed them was trying to copy the BMW and Infiniti with a four-door sedan," said Johnny Nocera, an exotic car dealer/car clinic talk show host in Naples, Fla. He claims to have a 40-person waiting list for Avantis. "Today you can't make the economics of building only 100 or 200 cars a year work unless you charge about $100,000 each."

"If they did what Porsche did-improve on the original a little bit at a time-they might have made it," said Tom Kellogg, a member of the original Avanti design team. "But Cafaro went overboard. He gave up some of the lines that made the car a classic. Now Avanti is really little more than a name."

By September 1990, the entire workforce was laid off and the Youngstown plant was idled. A global recession that began that same year certainly didn't help the car's intended luxury market.

"It was sad the way it ended," Ungaro said. "I think a lot of people thought it wouldn't succeed, but it went farther than a lot of people thought it would."

All told, 405 Avantis were built in Youngstown. The company was besieged by lawsuits—including from the Miss Universe pageant, which was promised an Avanti as a prize that was never delivered, and the public relations firm that had helped build the myth around Kelly.

In the 2000s, both Kelly and Cafaro would end up in court again. This time, it was federal criminal court.

Before that, in 1999, Kelly said he'd bought the rights back to the car company, and a ribbon-cutting foretold production of a new Avanti, different from the classic model. He had resurfaced in Carroll County, Ga., near Atlanta.

Robert Andrews, one of the members of Loewy's team, had made sketches for a roadster. They were updated, and three prototypes were built in Pennsylvania, called AVX, for Avanti Experimental.

Seven years later, once again, amid great fanfare, Avanti was announced in Cancun, Mexico (a website still exists). By then, Kelly held citizenship in Belize and Mexico, and was deeply involved in the resort business.

On Dec. 22, 2006, two months after its opening in Mexico, and about two months before he was supposed to unveil a new Avanti at the Chicago Auto Show, Kelly was arrested in Florida by the FBI and accused of running a Ponzi scheme, defrauding 7,000 people—many of them retirees who were looking for investment income—out of more than $342 million. Prosecutors said Kelly sold timeshares in resort properties, with the option of leasing them to other buyers through a company he controlled.

Avanti was named as a relief defendant, receiving ill-gotten money from the scheme.

More than five years after his arrest, Kelly pleaded guilty to one count of securities fraud. He was sentenced to five years in prison and credited for time served—nearly six years. He faced additional charges of mail, wire and securities fraud, but was released to his home in Indiana for treatment for colon cancer.

After Avanti, Cafaro's next investment was U.S. Aerospace, a company to develop a laser guidance system, which was also beset by problems. Cafaro tried to enlist the help of the Youngstown area's U.S. House Representative, Jim Traficant. In Traficant's 2002 federal trial on bribery and corruption charges, Cafaro testified that he paid Traficant $13,000 for help.

Court documents also revealed he gave Traficant the use of an Avanti. Cafaro pleaded guilty to providing an illegal gratuity, and was sentenced to 15 months probation and a $150,000 fine. Cafaro was also later rapped on the knuckles for illegal contributions to his daughter's Congressional campaign. (His daughter, Capri Cafaro, later served 10 years in the Ohio Senate.)

Seven years to the day he was arrested, Kelly died at the age of 64 at home in Indiana, surrounded by his family. His obituary at Palmer Funeral Home's website omits his criminal record, but talks at length about his business ventures, saying, "The closest to his heart has always been Avanti."

The Mahoning Valley is still looking for its white knight, and the years have been no kinder to the area. The city's population loss has accelerated dramatically, from 115,000 in 1980 to about 62,000 today. Portions of the East Side—not far from where Avantis were built on the old Republic Steel site—have been given back to nature as the city struggles to match its services with its population.

The American auto industry has taken a beating since, too, and that's had an effect on the Mahoning Valley. Delphi Packard went into bankruptcy in 2005 and the following year closed many of its plants. The ones that didn't close—like in Warren—saw their workforce severely reduced.

The workforce at the General Motors plant in Lordstown eventually dwindled as well, peaking at nearly 15,000, but down to 1,500 per shift—with only one shift running—when General Motors announced that the plant would be "unallocated."

Like Avanti, General Motors had been given tax breaks to stay operational. Unlike Avanti, the reaction in the Mahoning Valley to GM's announcement wasn't disappointment. It was rage. It was one more blow to an area that could ill afford them, and was tired of taking them.

"We had a lot of cons come through," Ungaro said. "People like to take advantage of you when you're down and out."

He was talking about economic development in the 1970s and 1980s. It's not any less true now.

Vince Guerrieri is an award-winning journalist and a son of the Rust Belt. His grandfather took him to the Avanti dealership in Youngstown when he was a child.

Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify Raymond Loewy's role in at Coca-Cola.