Speed Kills Was A Car Zine For Fugazi Listeners

In happier times, you could read about Pavement and the NHRA in the same pages

Making his case for national 55 mph speed limits in the summer of 1988, Senator Frank Lautenberg brought out a well-worn highway safety slogan: "The statistics show that speed kills." Many of his colleagues, still working in the long shadow of the sixties counterculture, could have situated that grave warning in congressional testimony about flower-children in Haight warning each other off amphetamines: "Speed Kills!" And if you wandered into the right record store in Chicago in the early 90's, you may have seen a music fanzine promising drag racing, record reviews, and more: "SPEED KILLS."

For the uninitiated: a music fanzine was a kind of connective tissue. A local zine (pronounced "zeen", like maga-zine) could tell you about recent shows in your area, or present an interview with musicians who lived or worked nearby. Many published reviews for recently released music, with mailing addresses for independent labels and distributors. Everything wasn't analog, obviously. Usenet groups discussed music as far back as the 1980's, and by the late 1990's an mp3 could travel well enough on 56 kb/s for Napster to scare the RIAA. But to actually get music into your hands, and to hear it at its full texture, you could carefully copy an indie label's mailing address out of a fanzine, stuff a few bucks into an envelope, and wait by the mailbox. If you liked what you heard, and kept following that thread, massive ecosystems of D.I.Y. music opened up to you.

While some music fanzines took a caustic approach, many emerged out of irrepressible enthusiasm for their scene or their subject. The more present, immediate, you could make it for the reader, the more they could grab onto and understand why you love this thing so much that you can't hold it back. This is the kind of thing people say about car culture: bring someone with you to a race; bring them to a car show you're passionate about; bring them a souvenir at least, so they can touch a piece of it. Connect it somehow to the things that they're already interested in. Make your enthusiasm tangible. In the case of the fanzine, that means type and cut and glue your own zine for print, and and use it tell anyone who will listen: "I love this stuff! This stuff will change yr life!"

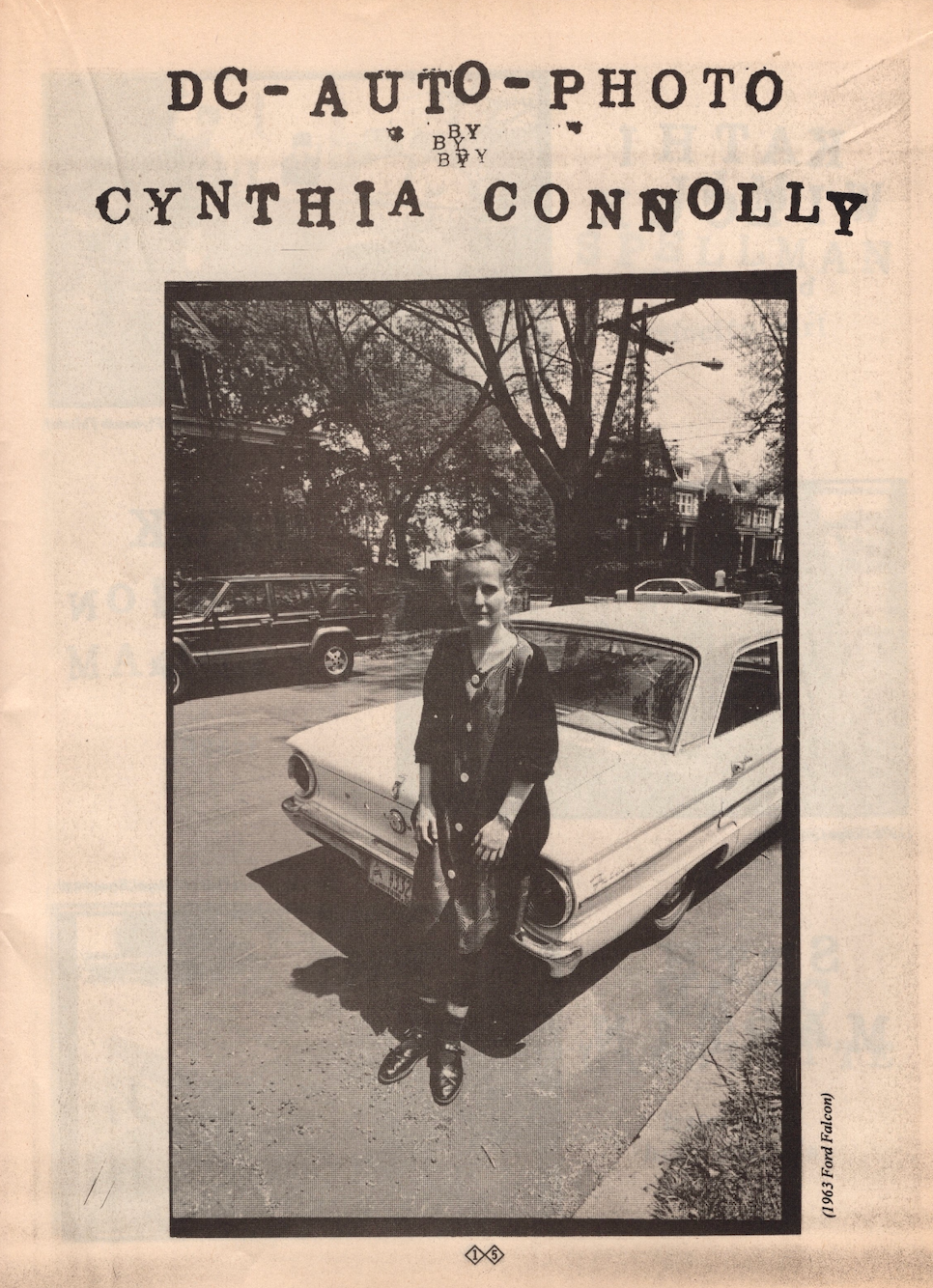

Chicago music fanzine Speed Kills, edited by Scott Rutherford, made its particular "stuff" clear when its first issue went to print in 1991. The hand-screened cover shows a cartoon skeleton in a dragster, and promises two interviews (Seaweed and Gas Huffer) plus "DRAG RACING! 60'S STYLE," and "LOTSA REVIEWS!" to identify itself as a music zine.

The music reviews in Speed Kills #1 are standard fare, pulling from the catalogs of Sub Pop, Merge, K, SST, and Drag City, among others. Reviews for Nirvana, Pavement, Smog, and Superchunk run across Speed Kills' newsprint pages, next to standard indie label ad-buys (and, in a little Speed Kills twist, vintage ads for auto parts.) It's not all tonal, structured stuff: two Trance Syndicate releases are recommended in the "gtr. fuzz tape collage damage" of Pain Teens and the "unnervingly demonic" tape loops of Crust. But a curious reader skipping the rest of the zine to check the reviews will have their eyes already in motion, past Harriet Records' Wimp Factor 14 and Chicago locals Wreck, into the next page. And across the page gutters from the last reviews, continued from page 21, is an interview talking about Ford and oil springs instead. Flipping back to page 21, we find the promised feature on drag racing.

The interview is with Larry Ammons, introduced here as "one of Cleveland's local legends!" Rutherford prompts and follows along, as Ammons talks about street racing in Cleveland, driving to Livonia to ask Ford engineers questions, and the Detroit Autorama. He tells anecdotes and talks about the cars he drove in the sixties, he rattles off names and specs. What's striking is the detail kept in the interview. In preparing it for print, Rutherford left the details in: as Ammons discusses the innovations he put into his Boss 429, he talks about journals, bearing surface, a model of carburetor. For someone picking up Speed Kills for the music reviews, who's never thought twice about what's under a car hood besides the recommended maintenance intervals, this is all alien. But the parties involved talk about it with total fluency, without pausing to explain. The curious reader flips to the music interviews for something grounding. What's the deal with Gas Huffer? Well, in boxes throughout their Q&A, you'll find quick, readable, mildly sarcastic instructions on how to replace the rear main seal on a crankshaft.

This was the connective tissue that Speed Kills provided: you're already here to see what the curious, creative, weird people of the world can do when they get their hands on music; wait until you see what they can do with cars.

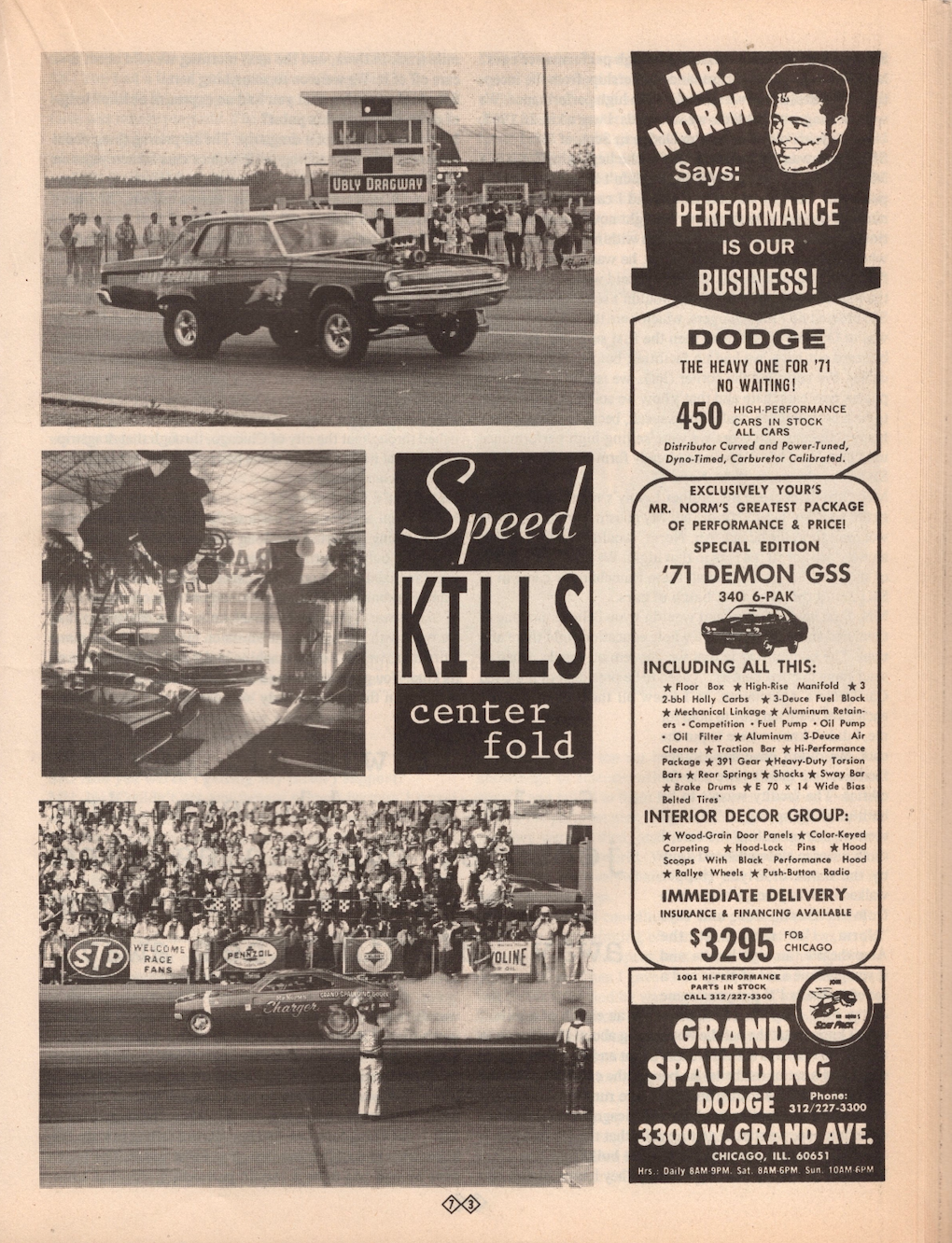

The received wisdom about subcultures is that this could never work. Surely, if you like drag racing, you're blasting "I Can't Drive 55" from your car stereo, not reviewing records from the label that put out Double Nickels On The Dime. These are decades-old Types of Guy locked in ideological combat. But there's a useful frame for this in issue #6's feature on Hot Rods From Hell. Speed Kills correspondent Rich Dana describes the group's purpose: "To seek out new life in a racing style mostly overlooked since the big bucks of corporate-sponsored funny cars and top fuelers eclipsed it in the early seventies." HRFH organizer Scott Jezak concurs, and Dana quotes him as saying: "Funny cars now are basically tools to get down the track... I love to watch them run, but drag racing today lacks character and individuality."

In 1994, John Force and capital-F capital-C Funny Car may not have been NASCAR or F1, but for these drag enthusiasts closer to their hobby's margins, everything is relative. Is this so different from how D.I.Y. labels hand-dubbing cassettes looked at Sub Pop, even before their Warner takeover? Sub Pop still oversaw great records after 1995; you still love to watch Funny Cars run. But if you want something tactile, something accessible, you have to get lower to the ground.

In that same spirit of the Hot Rods From Hell, seeking out the visible hand of the other human, Speed Kills faithfully devotes review space to small labels. This isn't to say that its top-fuel brand ever lets up for long. The eye catches on bands with automotive-themed names among reviews: Cheater Slicks, Fastbacks, Alcohol Funnycar, Voodoo Gearshift, Crain. But space is made for music that only exists as the painstaking work of people with day jobs and tape recorders. Speed Kills often features short but glowing reviews for Refrigerator, brothers Dennis and Allen Callaci of Shrimper Records. Shrimper, best known as the first home of prolific rockers the Mountain Goats, is based in Claremont, CA; ten miles from the old NHRA headquarters, and thirty from Riverside International Raceway. A Speed Kills review of a neighboring label's split single demands: "What the hell is going on in Claremont?" What, indeed, was going on just north of the Pomona Raceway? Speed Kills gave up trying to answer that on at least one occasion. Sidestepping an actual review of the hypnotic, churning rock of Shrimper alumni Halo, the SK review section rambled instead about the '68 Chevy Impala 4-door on their CD's cover.

Throughout its run, the staff of Speed Kills negotiated its two primary sensations—speed and sound—this way, one turning into the other. An interview with 1978 NHRA Champion Kenny Cook reveals mid-way that Cook's brother Jon plays guitar with Louisville rock band Crain (friends of the magazine), and that Kenny fixes the band's tour van. When Speed Kills sent out Issue #5's "Fave Car Survey" questionnaire, it drew responses not only from John Pearley Huffman (formerly of Car Craft), but from mischief-maker Nardwuar, Merge Records' own Laura Ballance, and Steve Albini. An interview with musician Eric Lunde gets loose halfway through, and leaves music behind for a long discussion about the aesthetics of collision, and the sacredness of Figure 8 crashes.

In one of its strictly automotive features, Speed Kills opted for a different kind of zine scene report during its run: interviewing Chicago's own Norm "Mr. Norm" Kraus, legend of Grand-Spaulding Dodge and drag racing innovator, at length. The interview is introduced "brought to you by the Speed Kills Historical Society!" in jest, but it gets quite literally down to nuts and bolts. You can almost hear the joy, reading Norm Kraus's answers about the kinds of custom work they did for customers, making their cars faster: "We found out that the 383 bearings worked better than the Hemi bearings!" Asked about performance and weight, he goes on at length about the '67 Dart, about the manifold being too close to the steering coupling in early tests. He talks about how he ended up in racing, and slides into long lively anecdotes, dutifully transcribed and giving a feeling of constant easy motion. His sense of where things were on the cars and how each part he altered would make things faster, who he worked with and where he was, his tactile feeling, all comes through clear and sharp. The "Mr. Norm" interview runs long, split in half and pushed to the back of the 6th issue, to hold all of these details. The interview is original work, valuable work, and can't be replicated or re-done. Norm Kraus passed away in 2021.

Last summer I was mailed a heavy cardboard box. Inside was a stack of music fanzines, scattered issues, all from roughly the same early 90's period and with some interesting niches. The Tim Alborn/Harriet Records zine Incite! interviewed librarian-musicians in its 28th issue, asking whether they preferred Dewey Decimal or Library of Congress systems. Another zine, Escargot (eds. Jeanne McKinney, Kathleen Billus, and Windy Chien) had detailed information about getting online in 1995, from picking an ISP to netiquette to UNIX commands. Issues #5, #6, and #7 of Speed Kills came to me among these other enthusiasms, a kind gesture from a friend sending me research material. Digging through the reviews, wandering back through the features, I got the gist of Speed Kills and set it aside to keep sifting through all the material on hand. But I kept coming back to the 6th issue, which had originally been mailed out with a Superchunk single. I hadn't heard of Speed Kills, but I wondered if any of my Superchunk devotee friends had seen the name, or had a copy.

The 6th issue of Speed Kills is easier to find than the early issues. Because of the Superchunk single, an item with reasonable demand and value for collectors, copies of issue #6 are more likely to have been bought, bagged, stored, indexed, along with the 7". There's a very real possibility that the interview with Norm Kraus, in all its great energy, all its detail, will survive for a drag racing enthusiast further down the line to study and enjoy, well beyond the bounds it might have otherwise.

And on the level of sheer enthusiasm: I myself hadn't given drag racing or hot rodding much thought, before digging into these. Now my ears perk up when I hear news about the NHRA, or when I see old issues of Car Craft by the antique store rows of Road & Track. Scott Rutherford and the rest of the team who made Speed Kills poured their effort, their time, and their love for their own niche of car culture into the zine, and that reached me still in 2024. It brought me along, and it told me the only thing I needed to know: they loved this stuff. This stuff could change yr life.