Read Nixon's Never-Delivered Speech In The Event The Moon Landing Failed

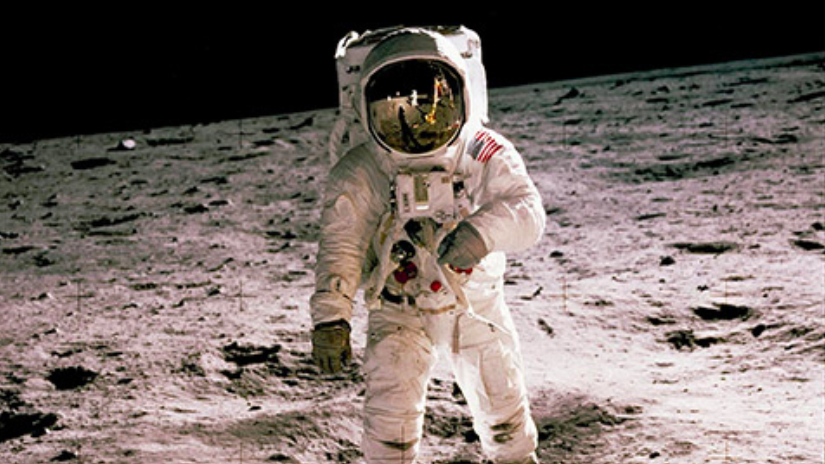

It's been 50 years since American astronauts landed on the moon, and it remains one of the single greatest achievements of modern human history. The moon, as it turns out, is really, really difficult to get to, and the fact that we pulled it off at all in 1969 is incredible. So incredible, in fact, that the very real possibility of its failure is almost nearly forgotten.

In 1969, William Safire, who served as President Richard Nixon's speechwriter, was asked to prepare a speech in the event that the Apollo 11 mission failed. The ask caught him off-guard, as he recalled during a July 18, 1999 interview with Tim Russert on NBC's Meet the Press.

"I remember when Frank Borman, who was the astronaut who acted as a liaison with the White House, called me up and said, 'You're working on this moon-shot. You'll want to consider a, uh, alternative posture for the President in the event of mishaps.'"

Mishaps. A delicate way of putting a potential catastrophe that would involve two dead astronauts before the eyes of the world, and a disaster for space exploration in general. He continued:

"... that was, as far as I was concerned, gobbledegook, and I didn't get it," Safire continued, "until he added, and I can hear him now, like 'What to do for the widows.'"

A number of things could have failed and resulted in the deaths of Commander Neil Armstrong, lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin and command module captain Michael Collins. The ship could have exploded. The lunar module could have failed to dock, thus stranding the astronauts in space. Scientists weren't even really sure if the surface of the moon was safe or not.

"At that time, the most important, the most dangerous part of the moon mission was to get that lunar module back up in orbit around the moon and to join the command ship," said Safire. "But if they couldn't, and there was a good risk that they couldn't, then they would have to abandoned on the moon."

He added, "Left to die there. And Mission Control would have to—to use their euphemism—close down communication. And the men would either have to starve to death or commit suicide. And so, we prepared for that with a speech that I wrote and the president was ready to give that."

The speech is short. It is titled, "In the Event of Moon Disaster" and it reads:

Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.

These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice.

These two men are laying down their lives in mankind's most noble goal: the search for truth and understanding.

They will be mourned by their families and friends; they will be mourned by their nation; they will be mourned by the people of the world; they will be mourned by a Mother Earth that dared send two of her sons into the unknown.

In their exploration, they stirred the people of the world to feel as one; in their sacrifice, they bind more tightly the brotherhood of man.

In ancient days, men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations. In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood.

Others will follow, and surely find their way home. Man's search will not be denied. But these men were the first, and they will remain the foremost in our hearts.

For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.

A small note at the bottom of the speech advises that, prior to making the statement, the president should also call "each of the widows-to-be." And that after the president makes the speech and when NASA ends communication with the astronauts, "a clergyman should adopt the same procedure as a burial at sea, commending their souls to 'the deepest of the deep,' concluding with the Lord's Prayer."

The speech is also dated on July 18, 1969, two days before Armstrong and Aldrin set foot on the moon, which means that both NASA and the Nixon Administration were already prepared for a stranding.

D-Day was much the same way; another sweeping triumph that we rally behind. Today, we celebrate it as the biggest seaborne invasion ever, where we successfully liberated Nazi-occupied France and helped the Allies win the war. But what if the mission had failed?

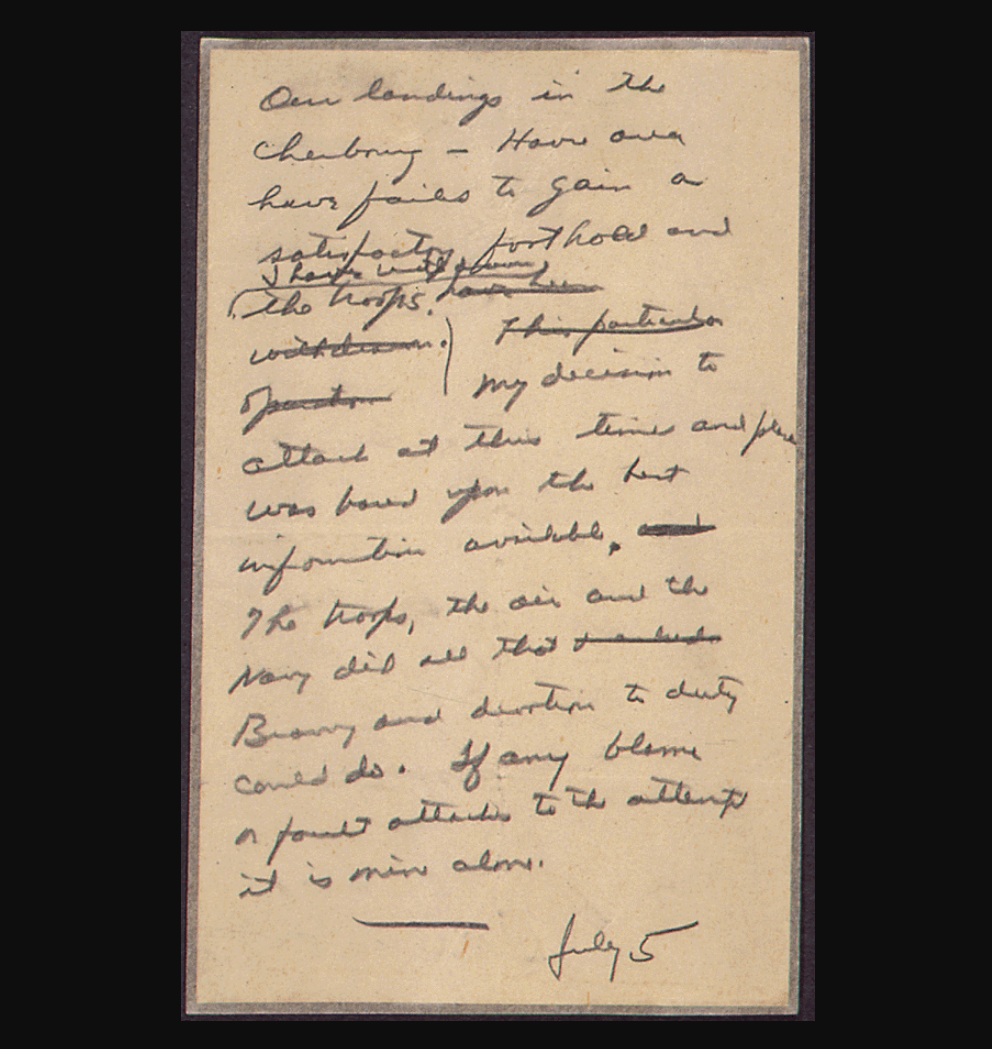

Failure was definitely on Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower's mind at the time. He composed a note he would have to deliver if things went badly. It, too, is short and reads:

Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available. The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.

You can see a scan of it below.

It's interesting to see that Eisenhower crossed out "this particular operation" and instead put "My decision to attack," thus signaling his willingness to accept all responsibility should we have lost. And he underlined, in an apparently violent rightward slash, "mine alone."

Ultimately, that note was unnecessary, but it also is evidence of a victory that we project as easy and given but was actually dangerous and fraught with risk of failure.

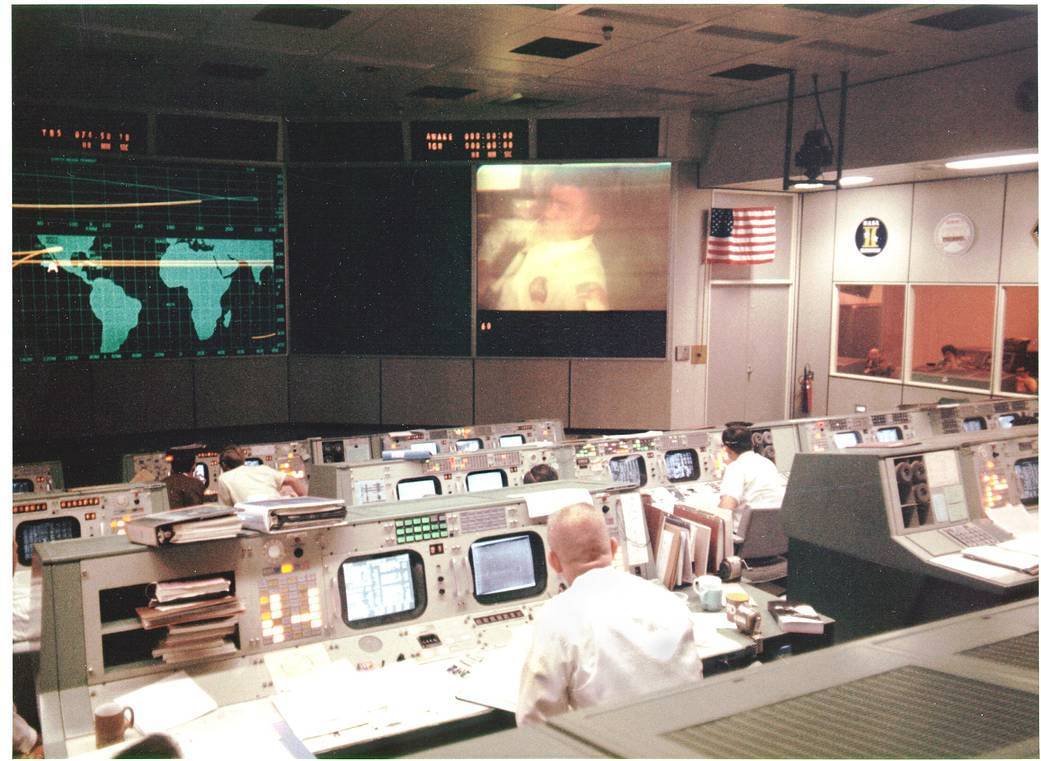

NASA is one of those agencies that we like to think of as never failing. The quote "Failure is not an option" from the 1995 Apollo 13 movie is attributed to NASA Chief Flight Director Gene Kranz. It depicts the failed mission and subsequent safe return to Earth. It's spoken by Ed Harris, who portrays Kranz, but the truth is the term apparently never originated from Kranz.

Nevertheless, it's a motto that both Kranz and NASA adopted. Kranz published his autobiography in 2000 and used it as his title. In 2004, it was used again as the title of a historical NASA documentary. And if you search the phrase on NASA's own website, you hit on a titled photograph of Kranz that's captioned:

Gene Kranz (foreground, back to camera), an Apollo 13 Flight Director, watches Apollo 13 astronaut and lunar module pilot Fred Haise onscreen in the Mission Operations Control Room, during the mission's fourth television transmission on the evening of April 13, 1970. Shortly after the transmission, an explosion occurred that ended any hope of a lunar landing and jeopardized the lives of the crew.

There's no doubt what NASA pulled off with the Apollo 11 mission was heroic, the stuff of legends. But the reality was everything was extremely uncertain. The threat of death was extraordinarily high. Nobody knew what was going to happen. But we remember it the way we do because people were willing to take one of the greatest risks in human history.

"We have a tendency now to just assume that the moonshot, Apollo 11, was an enormous technical feat that exhibited great hope for mankind," Safire mused. "But the headline of 'Man Walks on Moon'—that will be looked at 100 or 1,000 years from now."