Please Enjoy My Favorite Detail About An EV Of The Early Crap Era

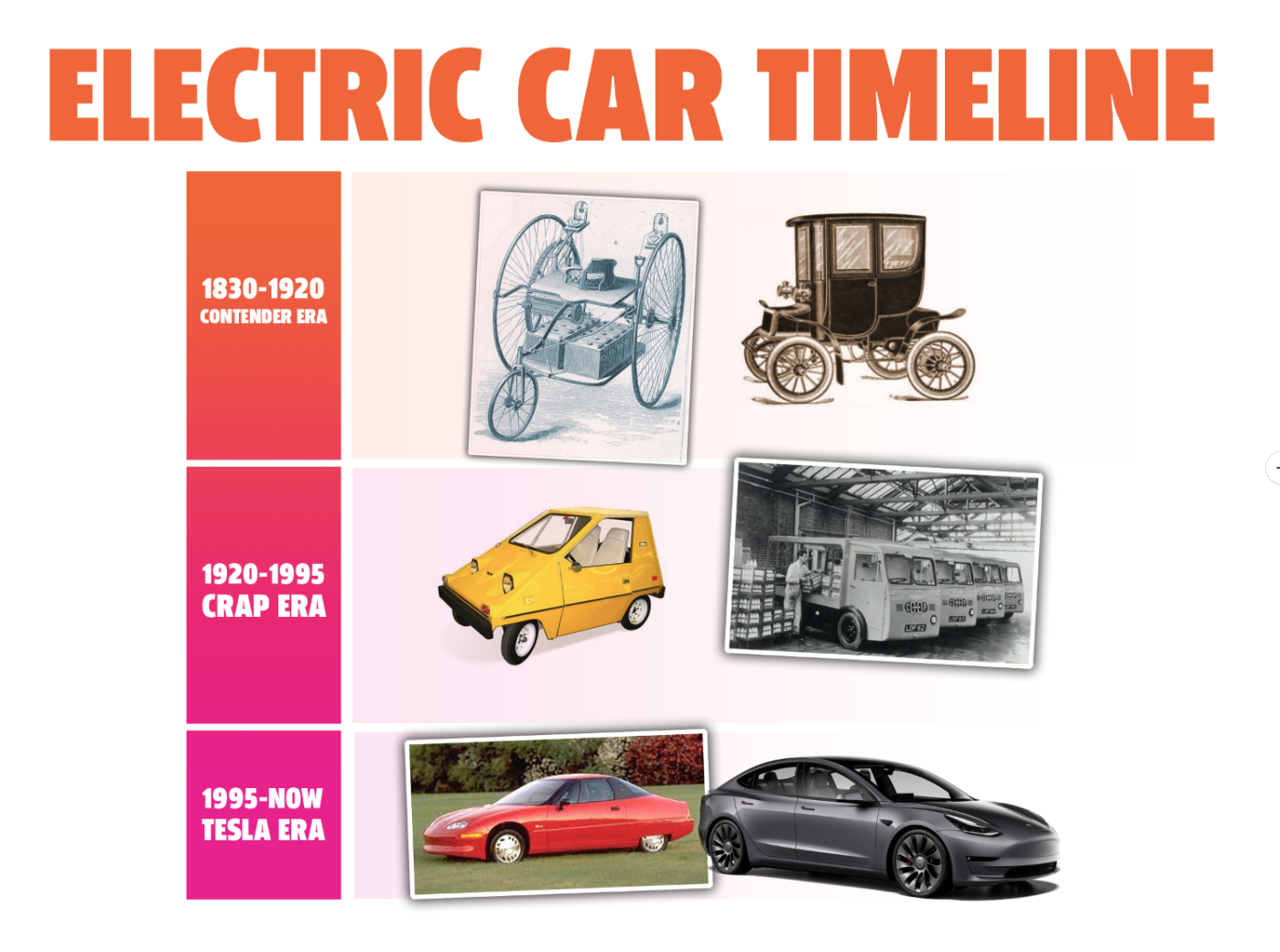

I'm not sure if you're aware of this, but I have a whole mental timeline for electric cars that divides their history into three categories: the Contender Era, when EVs and gasoline and steam cars were all equally plausible rivals; the Crap Era, when EVs developed their reputation for being slow, unusable shitboxes; and our current Tesla Era, which actually starts with the GM EV1. Today I just want to point out a fascinating detail of a Crap Era car, because I think it explains so much.

I will talk more about my EV timeline ideas soon — I just shot a little video explaining it, so, you know, stay tuned.

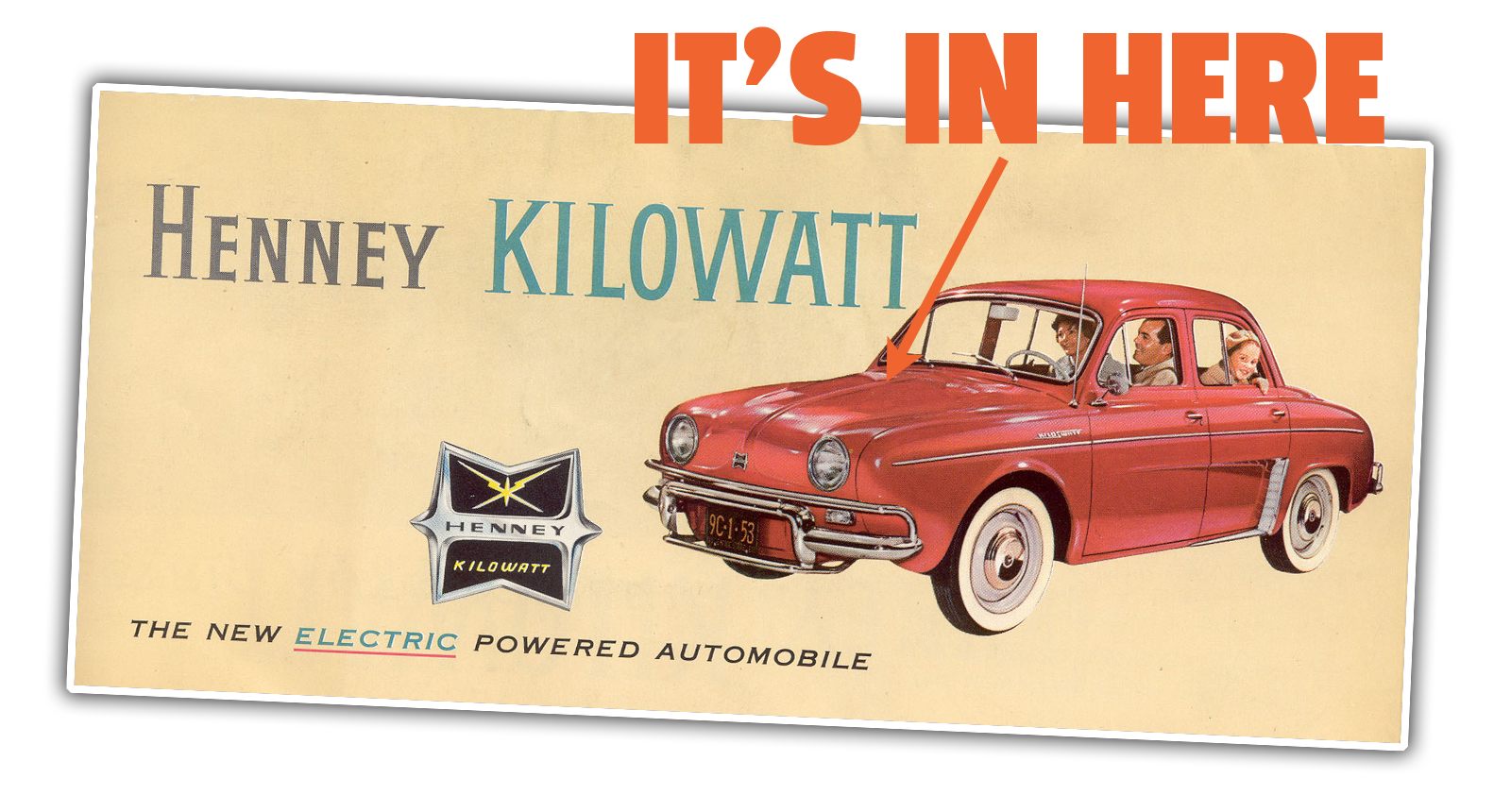

The Crap Era car I want to focus on is one of the best, in some ways, as it was a conversion of a car that is a genuinely charming little car: the Renault Dauphine.

The Dauphine was a lovely little rear-engined car, and in the U.S. for a while it sold reasonably well, being the number two import in America after the Volkswagen Beetle.

Renault didn't really have the dealership or service network to support the cars well enough, and the massive scale of America was a bit more than the cars could really deal well with, so by the later 1950s Renault was scaling back their American operation.

The Dauphine, though, was light and well-packaged and this didn't go unnoticed; in 1959 National Union Electric and the Henney coach-building company (who did work for Exide batteries) ordered 100 Dauphines sans drivetrains, with the plan to convert them to electric power.

Fitted at first with a dozen six-volt batteries that gave it a very symmetrically disappointing 40 mph top speed and 40 miles of range, and then later upped to 14 6V batteries that got those numbers to 50 mph and 46 miles of range, the Dauphine became the Henney Kilowatt, one of the first attempts to convert an existing car and sell it as an EV.

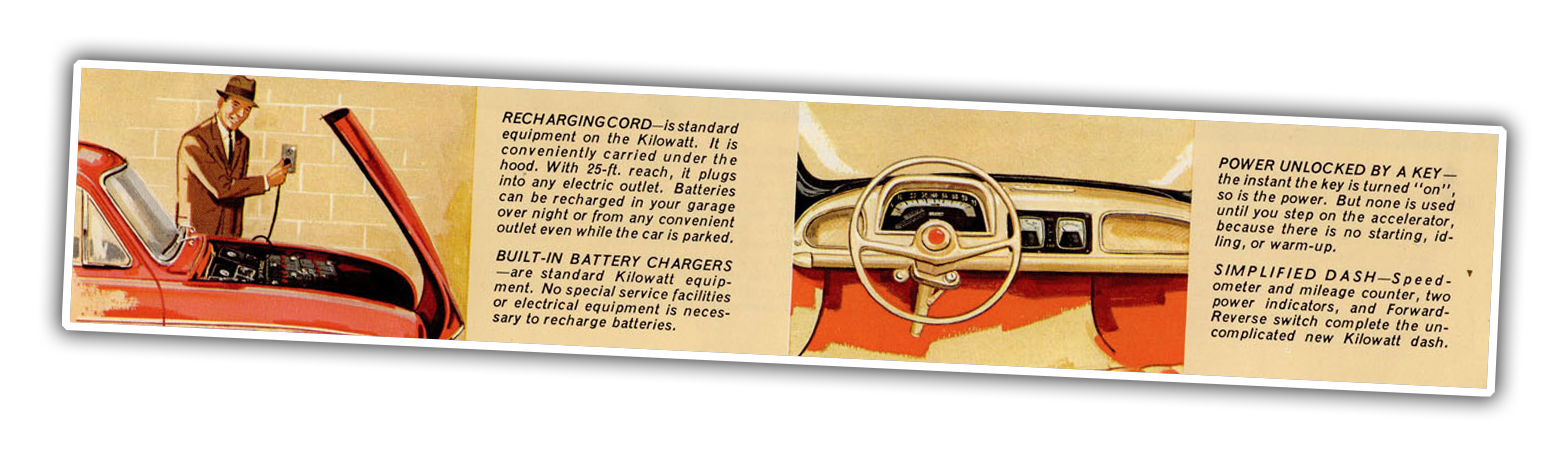

The conversion of the Dauphine into Kilowatt is a great way to see what the state-of-the-art was for EVs in mid-century America. All of the available space in the Dauphine's engine compartment and its trunk was completely consumed with bulky batteries and clunky motor controller and other electrical hardware.

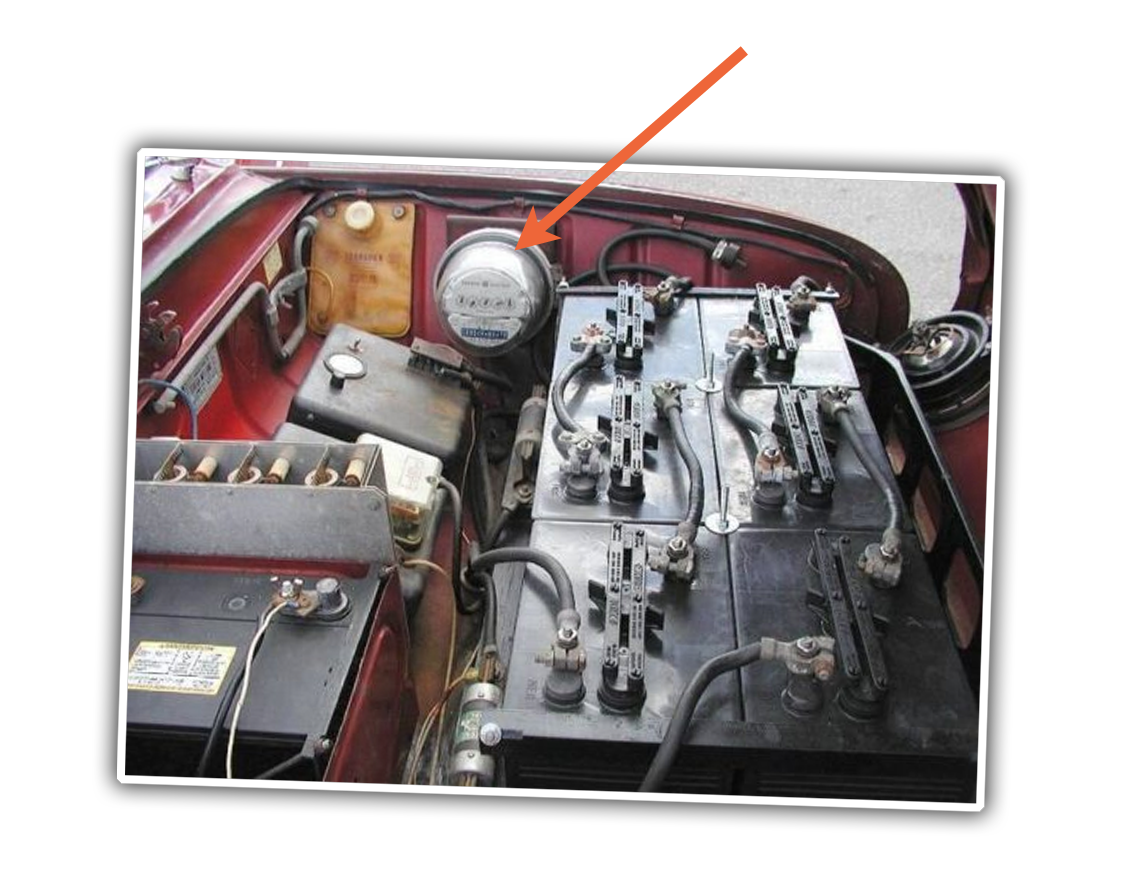

And that brings us to the detail I want to point out:

See that? That's an electric meter. The exact same kind of meter that you'd install on a house. They're still in use (in updated digital form) today! Here's a pic of one on a house, and in another Henney Kilowatt:

I've always found this absolutely insane. A house electric meter is huge, fragile, and designed to sit on the side of a very immobile house at precisely zero mph for decades at a time. The idea of using one in a car is absurd, and what it shows, better than paragraphs explaining it, is that at this point in time, nobody was thinking seriously about electric cars, and you can tell because to get a decent electric meter in this car, they had to use one designed for the side of a fucking house.

The Kilowatt was so ahead of its time that there were simply no good commercial automotive components around to build an effective EV, so we ended up with clunky solutions like this that look hilarious to modern eyes.

Today, of course, the equivalent of much of these electronics could likely be fit in a box you could comfortably hold in your mouth, if you were so dared. But the only way to get to this point is to start somewhere, and that's exactly what the Henney Kilowatt did — it got this difficult but crucial era of EVs going, so we could figure out all of the rough parts and make them better.

So, as we enter this bold EV era, take a moment to think about the Henney Kilowatt, and the shock that the 47 people who actually bought one must have felt when they opened the ex-trunk and saw the exact same thing inside there that the meter reader came by their house to check.