Piper PA-24-250 Comanche: The Jalopnik Airplane Review

The PA-24-250 Comanche was Piper's shot at the high performance, retractable (landing gear), piston single (single piston engine) market. It was also the only light civil aircraft to come with four, six, and eight-cylinder options from the factory. It's an important airplane, in its own way, and today we're going to review it

(Editor's Note: We got an email from a pilot who wanted to write reviews of small aircraft. Since none of us are pilots, and this seemed like a fun thing to do, we figured why the hell not? We fact-checked as best we could, at any rate. So this is the first of what may become a series of sky-car reviews.)

The Comanche’s Backstory

In the late 1950s through the 1960s, while the Big Three automakers were busy competing with higher-performance cars to sell to public, the Big Three of general aviation were dreaming up faster and more powerful planes to dominate the skies.

Beechcraft, Cessna, and Piper had each been enjoying successes since the end of World War II, but the demand for faster personal aircraft and availability of cheap leaded fuel in the ensuing decades drove each of them to develop four-seat airplanes with larger engines and retractable landing gear.

Beechcraft was the first out of the gate, originally selling the 180 horsepower Bonanza in 1947. It had a sexy low-wing design and ruddervators. By 1956, Beech's fork-tailed sensation had 225 HP and a claimed cruise speed of over 180 mph. Like a sports car for the skies, it was known for its nimble and satisfying handling, build quality, and propensity to kill pilots that overstepped their (or the airplane's) limits.

At the time, Piper's most successful aircraft was the Cub, a wood and fabric taildragger with 65 HP and a blazing maximum cruise of 85 mph. To compete, Piper would need to break out the drawing paper and start over. What design elements did they use? Laminar flow wing (just like the P-51 Mustang!) and retractable landing gear. It also had a spacious and aerodynamic four-seat cabin... and a weak 180 HP four-cylinder engine. Oops.

While it was faster than fixed gear airplanes, Piper realized it had brought sticks to a gunfight with the Comanche 180, and it just couldn't compete with the Bonanza.

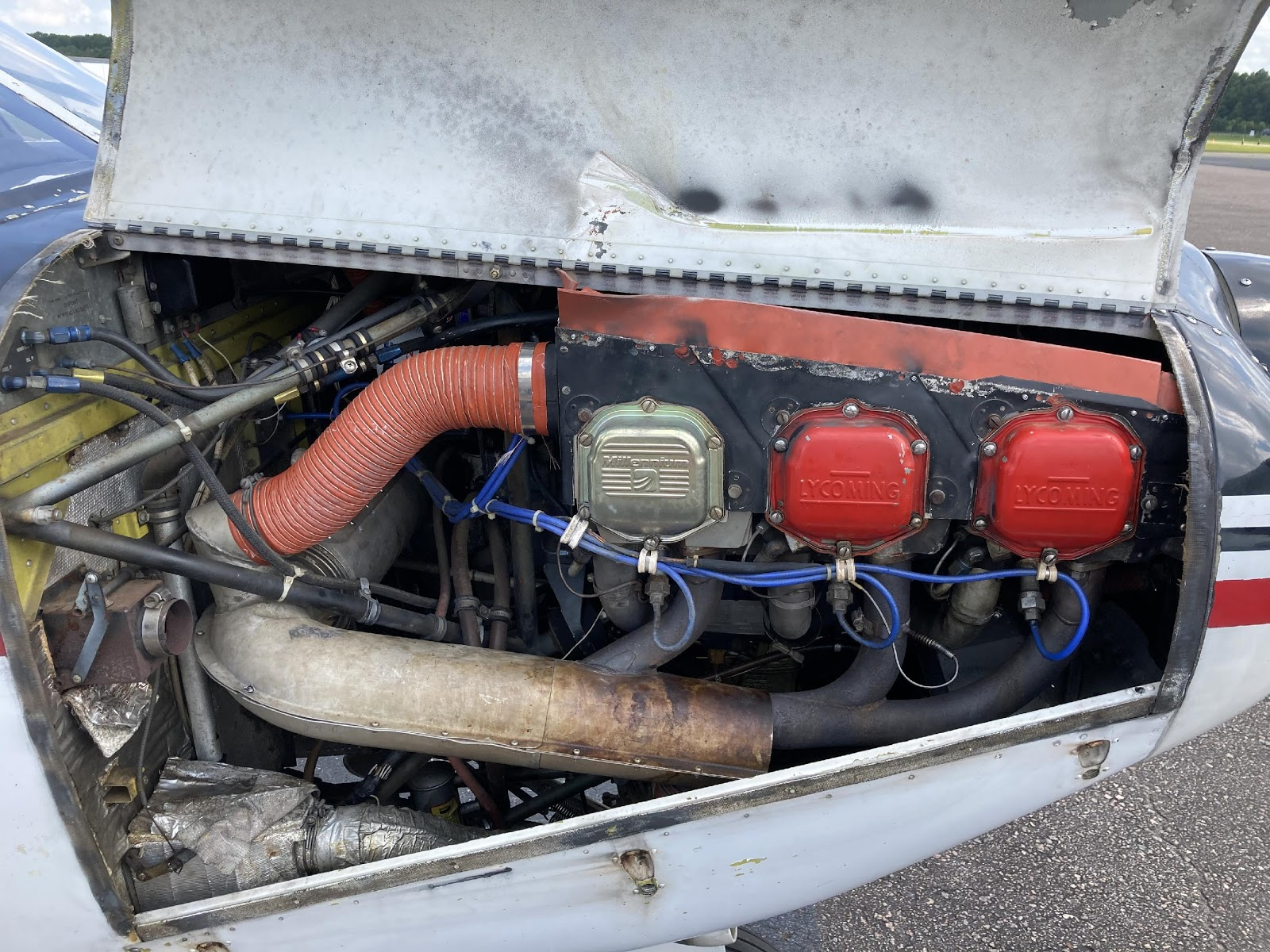

In 1958 it released the Comanche 250. Powered by a 540 cubic-inch Lycoming flat-six, the 250 HP version of the Comanche finally gave performance that could rival the Beech, and at a lower price. The better climb rate, cruise speed, and useful load of the 250 made it much more popular than the 180 and pushed Piper to go even further.

Using the deeply scientific formula of more engine = more better, Piper followed the muscle car trend and threw eight cylinders under the hood. In this case, a 720 cubic-inch fuel injected flat-eight with 400 HP at 2,650 RPM. With a 1,600 FPM rate of climb and cruise speed over 210 mph, the massive engine gave good performance, but was also the airplane's biggest flaw.

Fuel burns of 20-23 gallons per hour scared off many aspiring owners, and like a cheap AMG Mercedes, engine work could easily cost more than the value of the plane itself after a few years. Piper dropped the 400 after 2 years and, just like Hal and Lois Wilkerson, focused on making improvements to the better balanced middle child of the family.

Adding fuel injection bumped power to 260, and adding a window plus removing a cabin wall allowed fifth and sixth child-size seats on the 260B and 260C variants. Sales never did catch the Bonanza, and the Comanche was proving expensive to build. In 1972, the Lock Haven factory where the Comanche was built flooded, and Piper decided to focus on the slower and cheaper to build Cherokee line.

The Comanche Today

Walking up to the Comanche 250 today, one of the first things you notice is that it sits low to the ground with a nose-up attitude. The low, smooth wing and all moving stabilator give the impression of low drag, but the open front cowling and non-filleted wing to fuselage transition give the aircraft away as an older design. Entry into the cabin is via one door on the passenger side, requiring a quick step up on the wing and then climbing over the seat to get into the left or the back.

Once in the pilot seat, you notice that nose-up attitude and long cowl restricts your forward field of view somewhat while on the ground. It's no worse than in some comparable singles, but requires you to scoot your seat uphill to reach the controls.

Speaking of controls, I found the pedals closer than I'd like when I got the yoke where I wanted, but the seat and cabin width let me splay my legs where it wasn't too uncomfortable. Other than the heat.

It was a balmy 92 degrees the day of my flight, and while the Comanche has smaller windows than many other aircraft, the single door opening and credit card-sized vent window on my side did little to diminish the EZ Bake Oven experience. Naturally each side has a beautiful chrome ashtray.

A few pumps of the primer, throttle in slightly, key to start, and the carbureted flat six comes to life with a lightly muffled, big bore growl. The fan up front cools the cabin some, as long as you accept the noise of the open door. During taxi, the pedals feel initially stiff, but the nose steering is responsive, and all but the tightest turns can be accomplished without using brakes.

On the takeoff roll, pushing in the throttle to max power provides a decent shove, but far from heart-stopping acceleration. Minimal right rudder is needed to keep centerline, and the plane requires a light pull to rotate at 85 mph. Book numbers put takeoff distance at 750 feet on a standard day, but the takeoff roll was closer to 1,300 feet on our hot and humid afternoon.

Initial climb was right around 1,000 feet per minute with the gear up. Not a rocket by any means, but not bad for the conditions. Best rate climb speed is 105 mph and provides a decent aircraft attitude and view forward. As expected, climb diminished with altitude, giving 870 FPM at 3,000 feet, and 790 FPM at 4,000.

Still, 790 FPM is better than a lot of planes can do at sea level on a cold day. Since one of the main selling points of the Comanche was cruise speed, I decided to see what she could do at 6,000 feet. Using 24 squared (24 inches of manifold pressure and 2m400 rpm on the propeller) I got a two-way GPS average of 150 knots, or 173 mph.

Not bad, especially considering the hot day and the condition of my test bird, rented and kept outside for the past 15 years or more. Many owners have reported cruise of 155 knots true, and around 13 gallons per hour of fuel burn, which seems believable.

At cruise, the plane feels smooth with a good balance of stability and responsiveness. Light turbulence settles quickly and causes no noticeable lateral motions, plus the flat attitude gives a good forward field of view, and even a decent view of the ground in front of the wing.

Roll and pitch controls have good harmony, with a moderate force, and almost no rudder needed to coordinate turns. Roll response is moderately quick – nothing like an Extra 300, but still fun and about as fast as you'd want in a non-aerobatic aircraft, lest you get excited and your passengers involuntarily redecorate the interior.

Think sports sedan, not track toy. The net effect is a sense of speed (helped by an airspeed indicator in MPH vice knots) that you never really get in something like a Cessna 182. You even get enough airflow through the circular cabin vents to finally cool off.

Leaving the power up in a shallow dive gets you 200 mph quickly, and even pulling the power to idle, you don't want to plan on going down and slowing down simultaneously. Bringing the speed all the way back to a clean stall, you'll get the stall horn first, then some definitely noticeable buffet, then the nose drop around 80 mph. Plenty of warning and nothing scary on the drop.

Once back in the landing pattern, the airspeed and gear and flap changes turn something that was a minor annoyance into a real issue: The pitch trim is a horizontal window crank above your head, like an old Volvo sunroof.

Whoever's decision it was to make up-down changes a left-right crank must have either thought it was a great prank, or had almost no experience with airplanes. Or humans. This turns flying the pattern into an exercise in rubbing your head and patting your stomach simultaneously, and takes way too much mental energy, to the point where I just flew portions of the pattern out of trim.

Later versions had a more traditional up-down wheel located right below the throttle, but how the roof crank ever made it out of the factory is a mystery to me. Maybe focusing too heavily on which shade of chrome for the ash trays.

While you're busy fighting one snake in the cockpit, you notice the nice airflow from earlier has nearly died off, and the smallish windows mean you lose sight of the runway turning downwind. The good news is the well-balanced controls are still there and the flaps and gear give enough drag to correct from moderately high or fast. Also, the landing gear is built tough.

Why is that last one particularly important today? Remember that nose-high attitude from the ground? Yeah, it didn't go away while flying. Years of not flaring to land in the military may have eroded my ability to be particularly delicate while landing light airplanes, but I've got enough recent experience in them to usually avoid any major bouncing or negative comments from the other seats.

Not today. What I thought was a normal flare attitude resulted in bouncing the nosewheel, then the mains on the first try. Add power, go around, try again. Lower to the ground this time, flare a little too nose high, slightly overcorrect, hit the nose and mains simultaneously with a bit of a bounce.

"You may be slightly out of trim." Thanks. The last two landings I managed to grease the main wheels down, but still got a bit of a bounce on the nose. Whatever. I'm sure there's a way to get it right, but there's a reason many owners pump up the main struts or install a smaller nosewheel to get a flatter attitude on the ground.

Value

Prices for Comanches vary from about $35,000 for one with a higher time engine and older avionics to $110,000+ for updated C models. Getting into an airplane that hasn't been built in nearly half a century seems a little daunting, but the airframes are very corrosion resistant, and parts availability isn't too dire.

It's also one of the most commonly modified airframes, with several "speed mods" and auxiliary fuel tanks available to push range up to nearly 900 nautical miles. The march of technology is slow in general aviation (a new $750,000 Bonanza has 300 HP and cruises around 170 knots), so you're not giving up all that much performance by getting something old, just a bit of refinement.

My personal opinion? 90 percent of a flight is going to be gear retracted, moving quickly, and the Comanche 250 is a good balance of performance, space, and fun to fly for a fairly low price.

Just make sure it has a damn trim wheel. Maybe pump up the struts too.