NASA Issued The Plan To Return Humans To The Moon By 2024 But They Need $3.2 Billion To Get Started

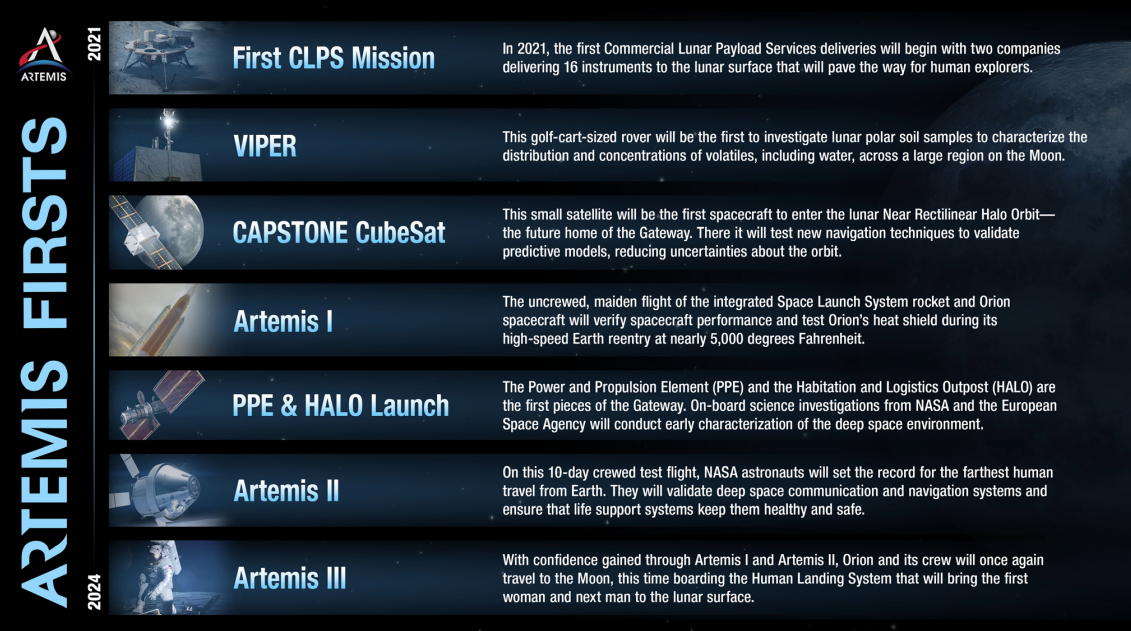

NASA released detailed plans to return to the moon by 2024 on Monday, landing the next human since the last Apollo mission in 1972, and, significantly, the first woman. This time, NASA plans for the moon are designed to be longer-term than the Cold War-era get there fast and jam a flag in the ground plan. The program, known as Artemis, will incorporate long-duration missions, establish a base at the lunar South Pole, place a permanent orbital station near the moon, and reach out to private industry for landing vehicles. They just need Congress to cough up $3.2 billion dollars pretty damn soon to get started.

If you want to read over the full proposal — and you should, it's pretty fascinating — you can see it all here and even download it and print it out if you want, because NASA is a government agency, so it's yours, enjoy.

Getting back to the moon by 2024 is a tight timeline, but NASA thinks it's doable if they can get all the $28 billion the multi-year program requires and not much goes too terribly wrong.

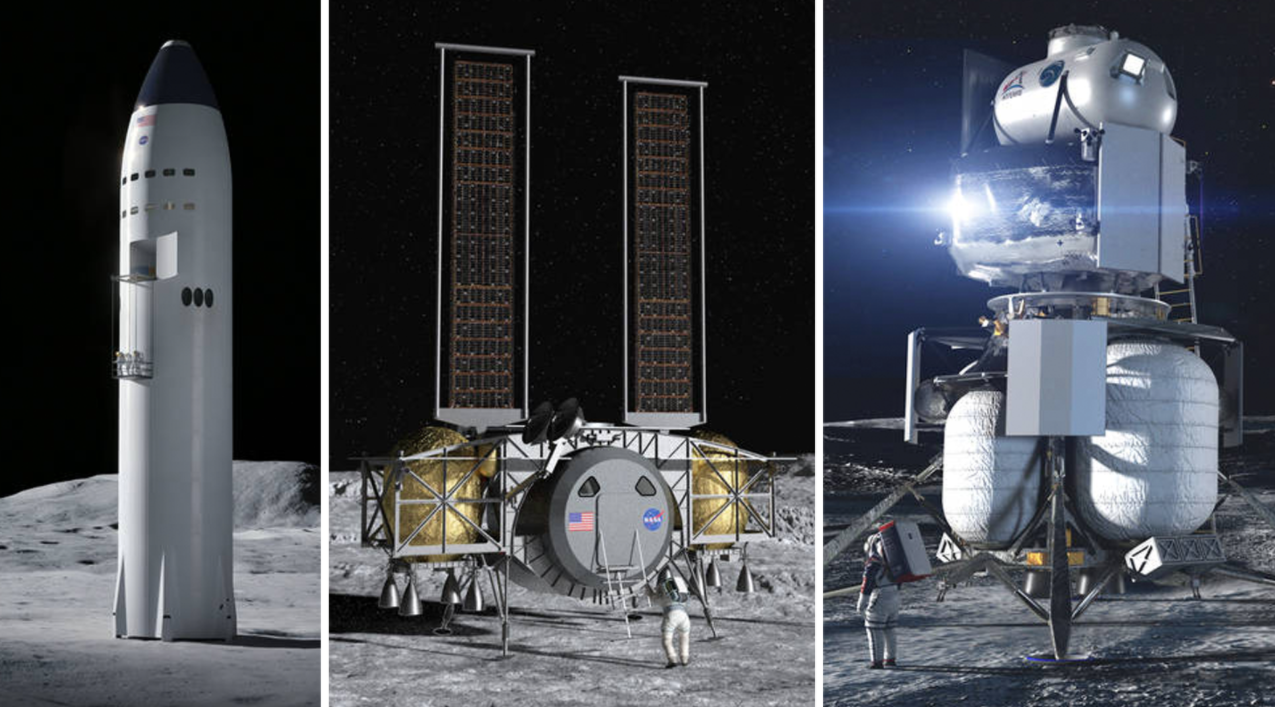

The key components of the Artemis program are the launch vehicle, the largely Shuttle System-derived Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, the multipurpose human-carrying spacecraft, the Orion, a space station designed to orbit the Moon called The Gateway, and the landing vehicles, which are currently being developed by Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX.

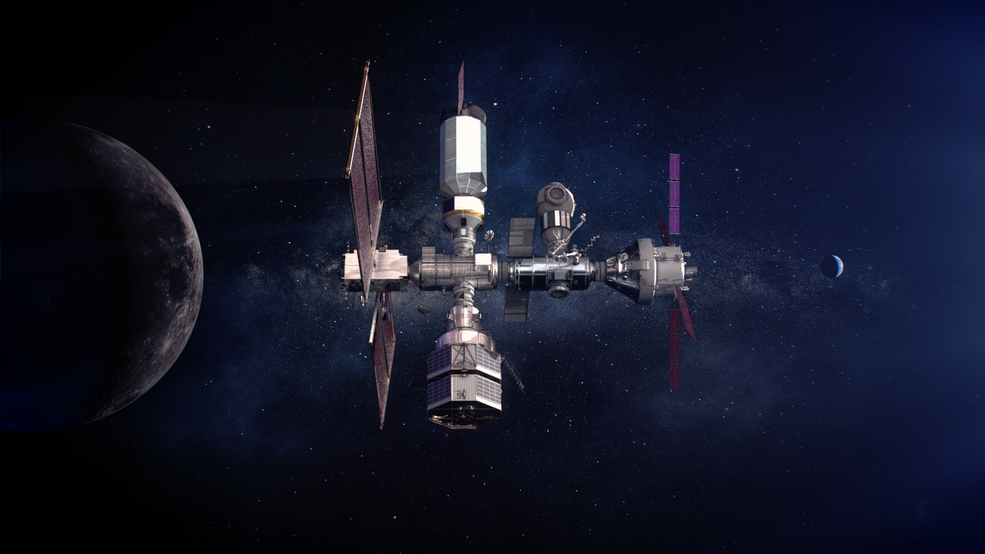

The SLS and Orion are quite far along in development, and, of course, are crucial elements. The Gateway, though not planned to be fully operational by the 2024 landing target date, will be partially completed and is also likely the component most crucial to the long-term viability of a human presence on the Moon.

The Gateway will provide a point for spacecraft to dock and refuel and resupply; it will allow landers to be re-used, and crewed vehicles refueled and resupplied for longer missions, including those to Mars. If there's any real game-changing element to all this, I think it has to be the role of The Gateway.

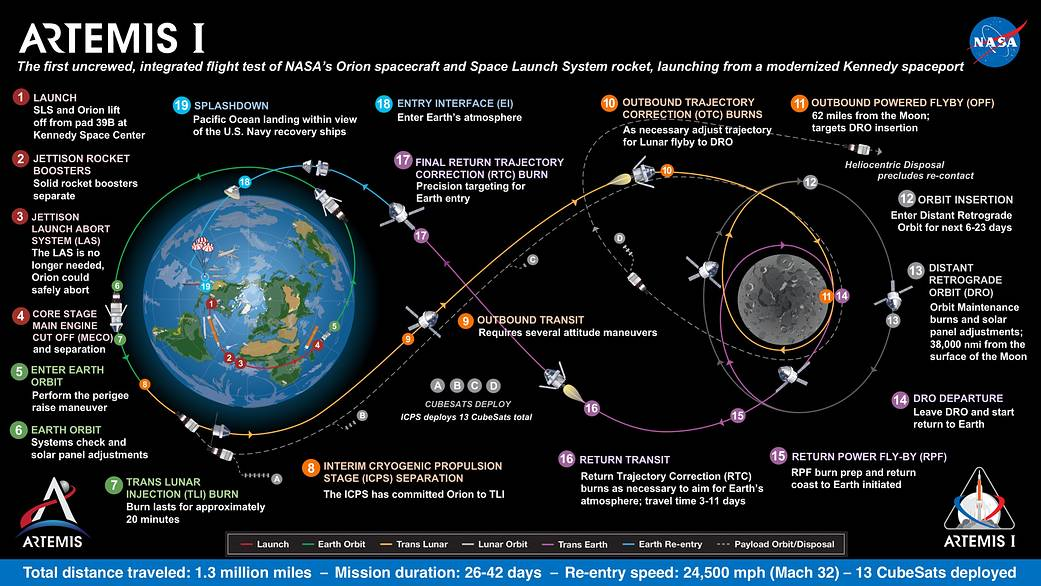

The first Artemis mission is an uncrewed shakedown mission to test the various components and is planned to launch late next year. It will send the Orion capsule farther into space than any crew-capable spacecraft has ever traveled. This is a big deal. The entire mission could take between 26 and 42 days, by far the longest ever mission for the start of a new program.

Here's a good video outlining what the Artemis I mission will do:

Or, if you like these big space mission charts (I definitely do), here's the one for Artemis I:

The orbit of the Orion spacecraft will be on a free-return trajectory but will spend a significant amount of time in a very large lunar orbit—stage 13, the Distant Retrograde Orbit—which will take it as far as 38,000 miles from the surface of the Moon. At the other extreme, the Orion will also approach as close as 62 miles to the lunar surface.

The next Artemis mission, cleverly named Artemis II, will be similar, but will send four astronauts around the Moon, and will send the quartet the farthest humans have ever traveled in space.

This mission will test all systems and procedures needed for an actual lunar landing, including rendezvous and docking procedure tests with the SLS's interim cryogenic propulsion stage standing in for the lander.

Artemis III is the big moon-cheese quesadilla. The big difference here is that the Orion will dock with the landing vehicle in lunar orbit (future missions will likely have the Orion and the lander dock at The Gateway together) and then use that to land on the Moon.

Whichever of the three companies is that builds the lander for this first mission will have conducted separate tests and shakedown missions prior to this, in case you're worried about sending astronauts into an untested lander. NASA doesn't work like that, don't worry.

I'm pretty excited by what I read in the report; while there are all sorts of opinions about every part of this flying around the internet, I think the inclusion of The Gateway and an emphasis on doing things in a sustainable way this time around mean the Artemis program really could become more important and do more to change the scope of human space exploration than Apollo ever did.

Hopefully, Congress will toss them the cash they need to get started before the year is out. If they don't, well, maybe a GoFundMe?