Listen To A Race Car Too Fast For Its Own Good

With Ferrari booked for an appearance in Le Mans' Hypercar class, it is hard not to think of the howl of old V12s tearing up forgotten racetracks. When I think of a Ferrari engine at the greatest sports car race in the world, though, I think of this thing.

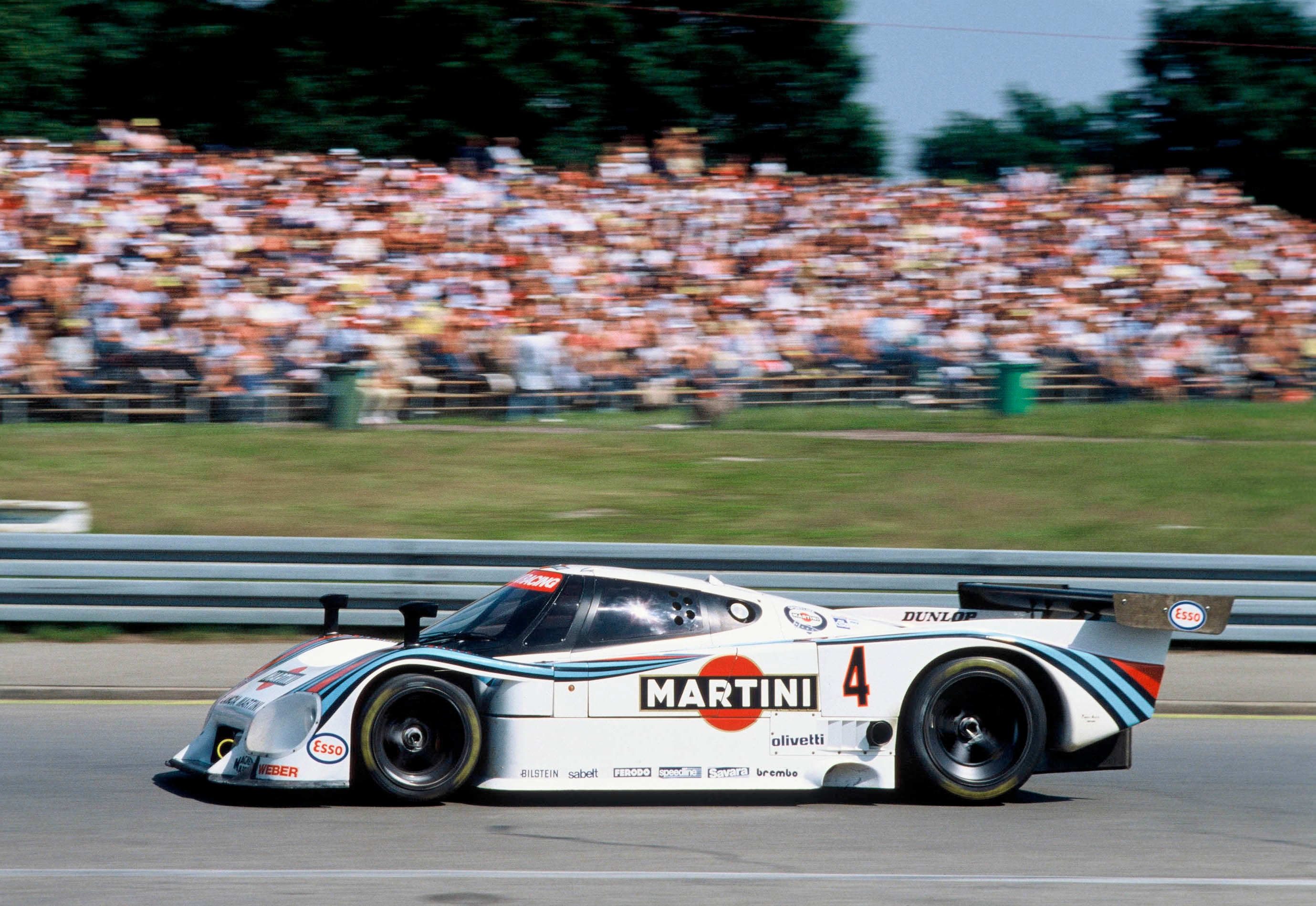

It's the Lancia LC2, the company's first Group C prototype. The YouTube algorithm sent me this video of one doing some dyno testing, and I could not resist the urge to post the vid and write about the car.

Watch as the tuner can't help but crack a smile hearing the turbocharged Ferrari V8 crackle behind him. It's a very different sound to other turbo V8s, like the earth-shattering rumble of the Mercedes that raced at the end of the Group C era. Here's actually a rare chance to hear one of those engines running naturally aspirated:

And for a bit more context, with turbos:

Back to the LC2. It's a weird car in that it didn't come around to replace a bad one. Its predecessor, the Lancia LC1, wasn't a slow car by any means. It repeatedly beat the greatest Porsche of all time, and it did it with a tiny 1.4-liter four-cylinder turbo. The only problem was that the LC1 was built to Group 6 regulations, and by the time it hit the race track, those had been phased out for Group C. No matter how much the LC1 won, it wouldn't count any points towards a championship.

So out went the open-topped LC1 and in went the closed-topped LC2. (There was an LC1 coupe that ran at the 1983 24 Hours of Le Mans, but I can't find a great deal of information about it. I also don't know the story behind this photo of it running without one of its doors!) Out, also, went the turbocharged 1.4-liter Lancia engine and in went a Ferrari V8, also turbocharged.

This was also very good, as I wrote back in 2016:

The car that replaced it was the LC2, pictured above, no longer with a little 1.4 liter four-cylinder but a big 3.0 liter Ferrari V8 with two turbochargers good for seven or eight hundred horsepower. The LC2 was amazingly fast, almost always on pole position when it competed with factory support from '83-'85. At the '84 Le Mans, a Lancia LC2 took pole a good 11 seconds faster than the next fastest Porsche.

But the car often blew up, with engine and transmission failures taking it often out of contention. And while Lancia was struggling to keep its Martini-backed factory cars in the race, Porsche was filling the entire entry list for races with privateer teams, completely gaming the system.

So Porsche outlasted the Lancia LC2 and we barely remember it anymore.

The thing was that Group C was all about endurance. It was fine to be fast, but that meant nothing if your car didn't last to the end of the race. It was also a fuel economy formula, and the LC2 drank too much fuel, as recounted by the wonderful Imca-Slotracing.com, a now-dead website run by a race team owner of the time.

Still, these were noble cars, as Imca-Slotracing details:

Without the works Lancias LC2 1983 Group C racing should have been of an unbelievable monotony. It were the lonely cars saving the public from an endless row of German machines fighting among themselves. But the public is not interested at all if the winner is a Kremer Porsche, a Joest Porsche, a Fitzpatrick Porsche, a Richard Lloyd Porsche, an Obermaier Porsche, a Brun Motorsport Porsche or a works Porsche. For the crowds that are all the same cars. But the crowds wish to see a combat of David against all that Goliaths. So Lancia had the nice (but impossible) role to play, and without the Lancias Group C could have died in its second year.

The weak points of the LC2 are all too interesting to be really bad. It made more power than its rivals (from 680 horsepower in its initial 2.6-liter configuration up to 828 HP as a 3.0-liter) so it drank more fuel. It was so fast, the team struggled to find tires that worked for it and wheels that didn't explode, as Imca-Slotracing details of Lancia's troubled 1984 season:

After Pirelli retired definitively from racing, Lancia had a problem to find the correct rims for the Dunlop tyres it had now to use. The solution seemed to be found in Speedline three-piece rims, specially made for the Dunlop tyres. During the winter the suspension was redesigned for the now required unique wheel-size. Also redesigned were the gearboxes. The aerodynamics were updated. Ultimate goal of all that hard work was to increase the reliability of the LC2 and its nervous handling. However, already at the first round, trying to win the pole, on his way to Lesmo, Patrese was victim of a split rim. So the three-piece rims, having so much contributed to a better handling, could not be used, and most of the work during the winter had been at no avail.

In its last season in 1985, the LC2 had grown so fast as to be called a "bomb on wheels," probably for better and for worse. They drank fuel so much they had to drive under their limit for most of their races, only getting to unwind at the end. This strategy was undone, in at least one case of the Monza 1000 KM, by a tree falling on the track and stopping the race early, as Imca-Slotracing recounts.

So the LC2 may have lost its important races, but it helped save Group C as a racing series altogether. There's something romantic about that, and it's what makes this car so endearing even to this day.