Labor Day Only Became A National Holiday Thanks To A Deadly Railroad Workers' Strike

We all enjoy a three-day weekend, but let's not forget the people who died to make it happen.

Labor Day has always felt a little bit like Senior Skip Day from high school. A day off? Just because we labor? Makes you think we should have these three-day weekends year-round. But like so many American traditions, scratch the surface of this innocuous federal holiday and you'll find rampant capitalism and bloodshed.

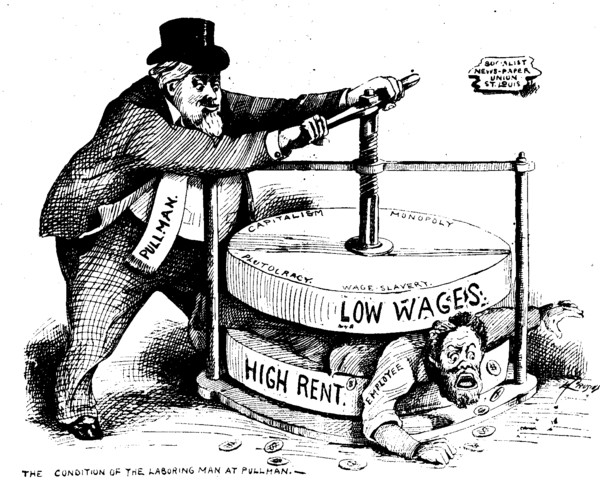

In the forgotten labor history of America, transportation has always played a big role. Decades before the UAW dragged the most powerful companies in the world to the bargaining table, there were the railroads and all the unions associated with their operation. The Pullman Railway Strike of 1894 would see 250,000 people walk off the job; federal troops broke the strike, with 30 people left dead. The reasons why those workers went on strike would be familiar to many of us today. Case in point, this political cartoon from a Chicago labor newspaper, which might as well have run in 2022:

To get to know the Pullman strike and how it radically changed America, you first need to know a little about the Chicago sleeping-car magnate George M. Pullman. Pullman was the son of a building mover, and he did well in the family business, getting hired to lift all of Chicago a few feet, according to Chicago Magazine. Able to buy his way out of serving in the Civil War, he instead spent his time creating and streamlining the production of opulent sleeping cars for trains. They weren't the first sleeper cars, but they were the first to explode in popularity. Pullman considered himself a Republican in the vein of Lincoln, and prided himself for hiring so many former slaves from the south that Pullman became the largest employer of Black Americans by 1900. He also was an early adopter of the concept of the company town, building neat little brick houses, a library, and the first indoor shopping mall in the midwest, all near the transportation hub of Chicago. The town of Pullman still exists, somewhat, as a neighborhood in that city.

But not everything was well in the Pullman factories and train cars. Black train porters were paid a pittance, relying mostly on tips from virulently racist passengers used to seeing Black people as chattel slaves. George Pullman is actually credited as one of the people who made tipping a cultural phenomenon in the U.S. The very hiring of these southern Black men was based on racist ideas of the docility and servile nature of recently freed slaves, according to the book Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of America's Labor Movement. These workers had a thick manual of rules and codes to live by, and were forbidden from eating in view of passengers or even sleeping on long cross-country routes. The hiring of Black Americans into low service positions reinforced the racial divide already present in every aspect of American life. White passengers would frequently refer to porters as "George," reflecting the notion that these employees were essentially owned by George Pullman. Black maids had it even worse, facing sexual assault and gender discrimination from both passengers and porters alike, all for even lower pay.

For Pullman Palace Car Company factory workers, life in Pullman, Illinois, was hard. Life was also closely controlled, with a messy lawn or fight with your spouse ending with a house call from your boss. The rents on factory-adjacent homes were incredibly high, even before the worst economic disaster in American history (at the time) hit in 1893. Pullman slashed wages and laid off workers, but didn't reduce rents. That left his workers destitute, sometimes with only a few dollars left to stretch for two weeks after rent was deducted from their paychecks. One Pullman employee claimed that, after his hours were cut and his rent was deducted, his paycheck showed he owed the Pullman company two cents. (He had the check framed.)

On May 14, 1894, Pullman workers walked away from their jobs in disgust.

Normally, such a strike may not have garnered much attention, but Pullman workers were members of the American Railway Union. From coal miners to longshoremen, industry and railroads west of Detroit began to shut down in the name of solidarity. The Pullman Strike would show the country and its powerful oligarchs the strength of labor. From Smithsonian Magazine:

...the Pullman employees were members of the American Railway Union, the massive labor organization founded just a year earlier by labor leader Eugene V. Debs. At their June convention, delegates of the ARU, a union open to all white railroad employees, voted to boycott Pullman cars until the strike was settled.

At the convention, Debs advised members to include in their ranks the porters who were essential to the Pullman operation. But it was a time of intense racial animosity, and the white workers refused to "brother" the African Americans who manned on the trains. It was a serious mistake.

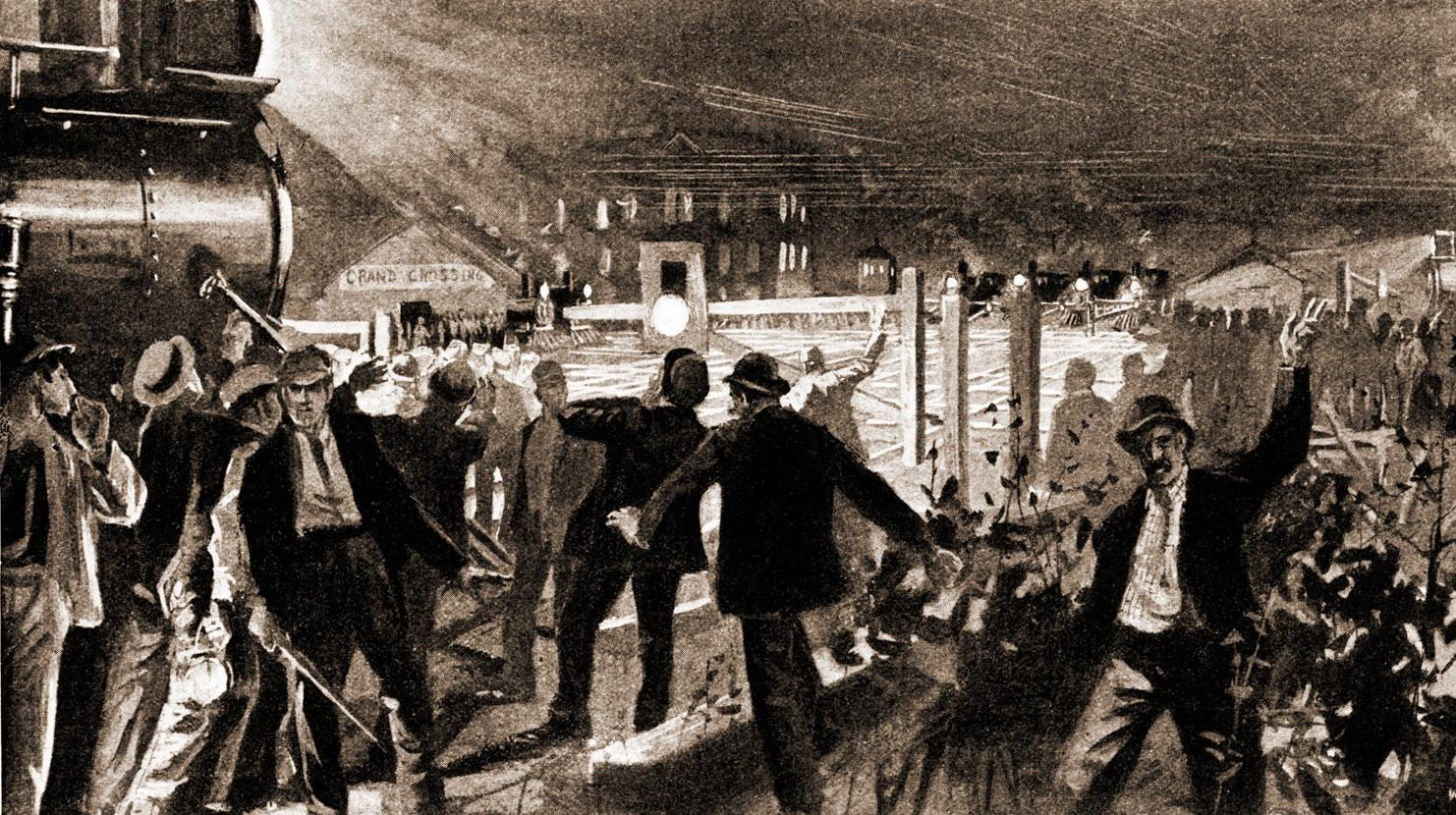

The boycott shut down many of the nation's rail lines, particularly in the West. The workers' remarkable show of solidarity brought on a national crisis. Passengers were stranded; rioting broke out in rail yards. Across the country, the price of food, ice, and coal soared. Mines and lumber mills had to close for lack of transportation. Power plants and factories ran out of fuel and resources.

George Pullman refused to accede to his employees' demand, which was to assign a neutral arbitrator to decide the merits of their complaints. The company, he proclaimed, had "nothing to arbitrate." It was a phrase that he would repeat endlessly, and one that would haunt him to his grave.

And this is how a rich, paternalistic oligarch, who saw himself as a patriot and hero to the downtrodden, ended up known as one of the greatest villains of the early American labor movement. Pullman got in touch with U.S. Attorney General Richard Olney, a practicing railroad lawyer, who managed to convince the courts to place an injunction on the union, making the strike illegal.

The strike continued, however, and snarled so much of the country that Congress put into place Labor Day as a national holiday in hopes of placating strikers. Before the strike, Labor Day was a holiday celebrated in only a few states, with Oregon being the first to pass a law recognizing Labor Day on February 21, 1887. New York quickly followed suit the following year, along with Colorado, Massachusetts, and New Jersey.

But one extra day off a year was not enough. These were workers who had jobs, but remained destitute under the yoke of their bosses both on the job and at home. When the legal wrangling and Congressional platitude didn't work, Olney convinced President Grover Cleveland to send in armed troops to break the strike, all without the individual states' approval. In the end, 30 Americans, mainly in Pullman's hometown of Chicago, would die in the riots, shot and bayoneted by their fellow countrymen. Thousands more were injured or lost their jobs.

While the strike was put down without any negotiations between labor and management, Pullman's reputation was in tatters, never to recover. When Eugene Debs, the labor organizer arrested for defying the court's injunction of the strike, was released from jail, a crowd of 100,000 people showed up to cheer him. He'd become a major force in organizing and strengthening unions. The strike also led to the first all-Black union in the American Federation of Labor, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. (Much to Debs' frustration, the brotherhood of the ARU voted to still only admit white workers into its ranks, even though some Black workers participated the massive strike.)

Compare Debs' fate to what happened to Pullman, according to the Smithsonian:

The federal commission that investigated the strike judged that his company's paternalism was "behind the age." A court soon ordered the company to sell off the model town. When Pullman died three years after the strike, he left instructions that his body be encased in reinforced concrete out of fear it would be desecrated.

A clergyman exclaimed at Pullman's funeral, "What plans he had!" But most remembered only how his plans had gone awry. Eugene Debs offered the simplest eulogy for his pompous antagonist: "He is on equality with toilers now."

Things haven't changed all that much from 1894. If railroad workers and management don't come to an agreement by September 15 on a new contract, those workers could head to the picket line, sending further ripples through the fragile recovering economy.

As we watch Jeff Bezos, CEO of the largest online retailer in the world and notorious abuser of his own workforce, get involved in rental housing during a historic housing crunch and skyrocketing rental prices, we have to ask ourselves if we are falling into the same traps that defined America's Gilded Age. During a time of unrestrained profits for companies, and seemingly unrestrained inflation for the rest of us, it's good for Americans to remember what can happen when working people don't get their fair share of the good times.