Ireland's Other Cars

Ask anyone to name an Irish car and the best they're likely to come up with is the DMC DeLorean, which was financed by Americans, largely designed by the British and built in the part of Ireland that remains in the United Kingdom. Absolute die-hards might name the Shamrock, a 1959 tailfinned, fibreglass abomination designed for US export, using Austin mechanicals. Ten of those were built before the factory shut down and all the remaining parts were, thankfully, dumped in a lake.

There was the TMC Costin too, a competent little sports car of the mid-Eighties designed by famed aerodynamicist Frank Costin. Around forty of those were built in Ireland by the Thompson Manufacturing Company, and the design was later bought by Dan Panoz, tweaked, and sold in the US in the Nineties as the Panoz Roadster. Apart from a handful of names from the early days—Chambers, Alesbury, Thomond—Ireland has never been a powerhouse of automotive production like Britain or France. But that's not to say that the country's car-building history is completely barren.

Driving into the village of Ballinascarthy from the city of Cork, visitors are greeted by the sight of a metallic, life-sized replica of a Ford Model T at the roadside.

Ballinascarthy is a small village, even by Irish standards. It's a case of blink and you'll miss it, if you're traveling along the road connecting Cork with the scenic west of the county. Lining the road for barely a quarter mile is a creamery, a filling station, a tiny grocery store, a used car dealer, and a pub with "Henry Ford Tavern" emblazoned in Ford-esque script above the door. In 1847, at the height of the Great Famine, William Ford left Ballinascarthy, ending up in Wayne County, Michigan. He became a businessman and married an American, Mary Litigot, before Mary gave birth to a son, Henry, in 1863. Mary was the adopted daughter of another Corkonian, Patrick Ahern, who had left the city of Cork around the same time as William Ford.

Young Henry idolized Patrick who regaled him with tales of the old country, which fostered a strong Irish identity in the boy. In 1912, he visited Cork and the house that Ahern had left, and the street name, Fair Lane, would later be bestowed upon his Dearborn mansion and on one of the company's models.

Bearing all this in mind, one can probably assume that it wasn't just Cork's deepwater port and geographical location that led the Ford Motor Company to set-up its first purpose-built factory outside North America there in 1917.

The Albert Kahn-designed plant, located at the Marina along the banks of the River Lee in Cork, was originally slated to build Fordson tractors with production beginning in 1919. By 1921 though, the first Model Ts were rolling off the production line alongside the tractors, and the facility was employing over 1,500 people, a figure which, within a decade, would shoot past 7,000.

In the 1922 divorce settlement between Ireland and the United Kingdom, the north-eastern corner of the country remained part of the U.K., becoming Northern Ireland, with the rest of Ireland becoming independent. One problem for the new Irish Free State (the precursor to the Republic of Ireland) was that the economy was almost entirely agricultural. Belfast, now in Northern Ireland, was where all the heavy industry was. They'd built the Titanic after all.

The Free State's only large factories were those of Guinness in Dublin and Ford in Cork.

Irish industrialists and government ministers began to look at Cork as a model for progress. In the past, it had primarily prospered thanks to its large agricultural hinterland and a trade in butter. By the early Thirties, it was, thanks to Ford, becoming an industrial city, its workforce better paid than any other in the country. If Ireland wanted to truly modernize, it would need factory workers, managers and foreign investment, not just small farmers. Some of those businessmen and politicians seemed to think that car production was the way to go.

In 1932, Frederick Summerfield approached the Minister of Industry Seán Lemass with a hare-brained idea about assembling cars in Ireland. If the Minister were to impose a huge tax on the import of Fully Built Up (FBU) cars, it would incentivize Irish entrepreneurs to start importing the cars in component form (CKD—Completely Knocked Down) and assembling them in Ireland using locally-sourced parts. Summerfield was of the opinion that, in addition to the jobs created by assembly, factories producing tires, glass, batteries, spark plugs and seats would spring-up, employing thousands more. The idea certainly appealed to Lemass, who, in the midst of a trade war with Britain, knew that unless Ireland established a capable manufacturing sector, the country would never be able to attract other foreign manufacturers like Ford. He greenlit Summerfield's idea and by the end of December, 1933, he was taking a Irish-assembled Dodge for a test drive around Dublin, a city on whose seagull-ridden cobbled streets horses and carts still acted as delivery trucks.

The scheme was, pretty much, an overnight success. Lemass had imposed a cap of around 500 FBU cars that could be imported in any given year. With demand for transport increasing, if the public wanted cars, they had to buy Irish and, if that demand existed, the market had to supply it. By 1935, a list of car brands being built in Ireland included Vauxhall, Adler, Chrysler, Mercedes-Benz, Peugeot, Hillman, Standard, Dodge, Hudson and Armstrong-Siddeley in Dublin. Fords, Studebakers and more Dodges were assembled in Cork. Not all manufacturers catered for the CKD system though. Fully-built Packards had to be disassembled in Detroit, the parts loaded into crates, shipped to Ireland and re-assembled in Dublin. There were, admittedly, some inefficiencies in Summerfield and Lemass' scheme.

When the Second World War hit, supplies of bodies, chassis and steel from Britain, the US and continental Europe ground to a halt. This was the death-knell for some of the smaller assemblers like Adler, Chevrolet and Chrysler. The larger ones managed to mothball themselves for the duration of "The Emergency," some turning to incredibly left-of-field methods to keep their workers occupied.

According to Bob Montgomery in his definitive book, Motor Assembly in Ireland, the Ford plant, which had been downgraded in 1932 to an assembly plant for the Irish domestic market, began sending its workers out to peat bogs near Cork to cut turf which was sold at the factory gates as home-heating fuel. The Marina's manufacturing capacity turned to carving wooden clogs for schoolkids, making screwdrivers from old valve stems and salvaging bent nails and timber from packing crates for resale.

When the first car, a Ford Prefect, rolled off The Marina's restarted production line in 1946, it marked the start of a period of domination for Ford in the Irish market.

In the early 1950s, Ireland was dirt poor. The roads were rough and rutted. With a deficit of used cars, people lapped-up the cheap, rugged little sedans from Ford despite them being dull, wheezy little things. Ford held around 30% of the Irish market, with one model, the Prefect, outselling all other brands combined. But it was about to gain some high-quality competition from the re-emerging Germans. The first Volkswagen assembled outside Germany was built by Motor Distributors Limited in Dublin in 1950 and today resides in VW's museum in Wolfsburg. Irish buyers took to the car for most of the same reasons buyers in other countries did—it was cheap and it was tough.

British cars were popular too. Irish-built Morris Minors could be differentiated from Cowley-built models by grilles and wheels painted the same color as the bodies. Another identifying factor across a whole range of Irish-assembled cars was a little shamrock etched into the side windows.

By the 1960s, with Ford Cortinas, Austin 1100s, Minis, Morris Minors, Volkswagens and Hillman Hunters, the big brands were all building cars which perfectly suited the Irish market—cheap, small cars, which could fit a big family (because Catholicism). That in-built conservatism meant that colors couldn't be too showy either, with the most common being black, grey and brown. That's not to say there weren't other, weirder makes assembled though. Alfa Romeo, Citroën, Panhard, Borgward and Messerschmitt were some of the stranger ones. Even Eastern European cars like Skoda and Wartburg had a showing. Ireland's motor assembly industry ran the gamut from Adler to Wolseley, though sadly neither Zastava nor ZAZ were ever built, though suitable alternatives from Fiat and NSU were certainly available.

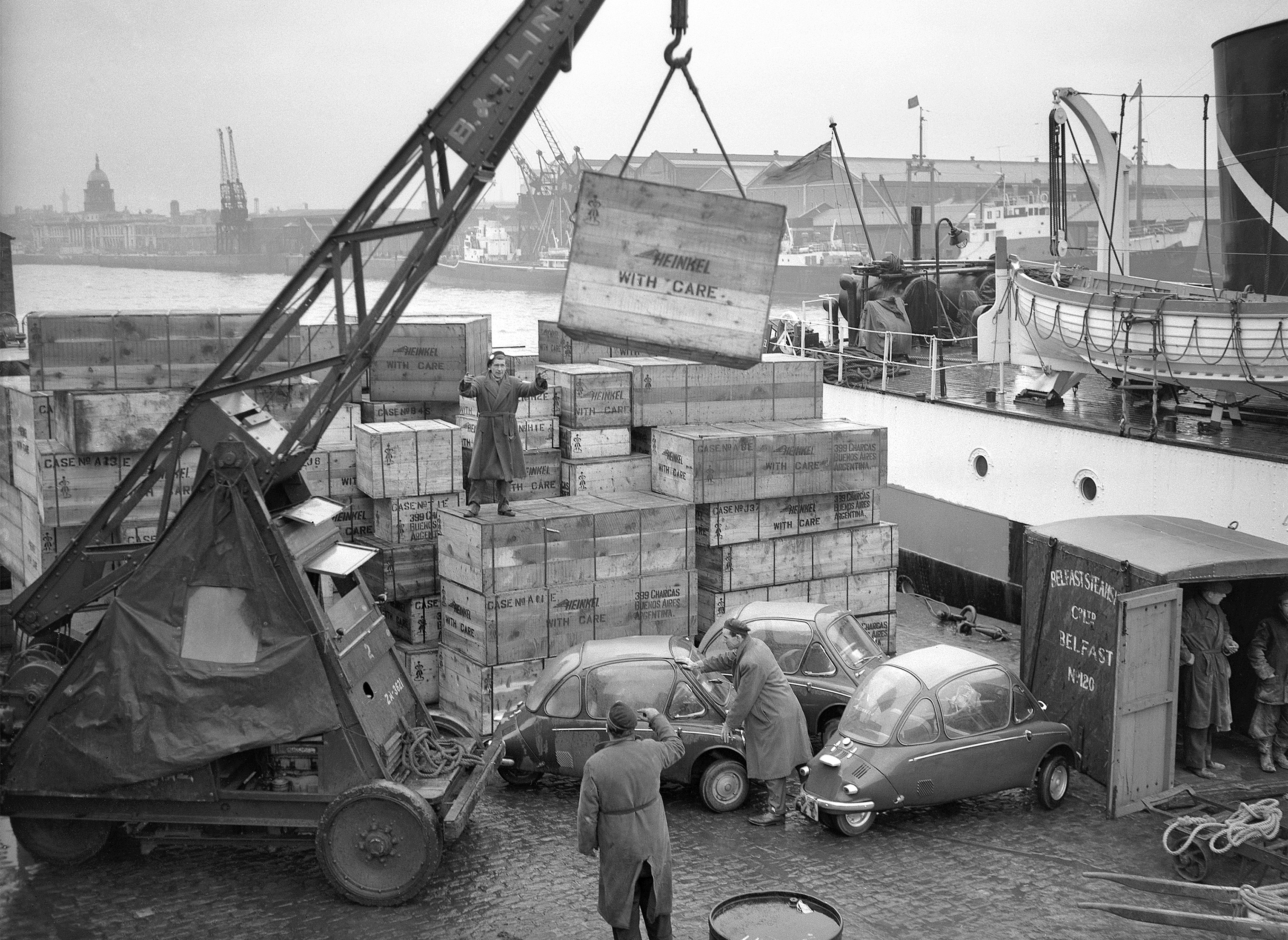

Factories weren't just confined to Dublin and Cork either. Nor did assemblers just put-together cars for the Irish market. When the Great Northern Railway works in Dundalk shut down in 1958, the town was faced with mass unemployment. The government decided to step-in and bought the full production rights to Heinkel bubble-cars. Heinkel, like Messerschmitt, was happy to divest itself of car production which it had only been doing as a stopgap while it waited for sanctions on aircraft production to be lifted. The Dundalk factory never came near the 6,000 units a year it needed to break-even, even if it did export cars to the US and South America in crates cutely labeled "Heinkel With Care". It shut down in 1961.

Renaults were assembled in the south-eastern harbor town of Wexford (in the county from whence the Kennedys came) from 1965 and working conditions there were pretty typical of the larger assemblers. Accidents weren't infrequent, the roof leaked, people set themselves on fire in the spray booth, chemicals were dumped into the Slaney estuary and new arrivals on the factory floor were slathered in grease as an initiation ritual. The Wexford plant exported Renault 4s to Italy into the Eighties, and for years the packing crates in which the bodies arrived were seen in back yards around Wexford used as garden sheds.

The two biggest things that would ever affect the Irish car market happened in 1973. The first thing was that assembly began on the first Japanese car sold in the country, the Datsun Sunny. Toyota Corolla production began a month later. In the late-Sixties, around a third of all cars produced in Ireland were from British makes with all their associated quality issues.

When the Japanese arrived on the scene with their conservatively-engineered but reliable cars offering a radio as standard, Irish buyers couldn't get enough and British cars rapidly fell out of favour. 1973 also saw Ireland joining the European Economic Community, one of whose central tenets was the promotion of free trade. Unfortunately for Ireland, the CKD system wasn't really in the spirit of things. One of the conditions of Ireland's accession was that CKD would be dismantled by 1984. That was still a decade away though and the assembly business showed no signs of slowing-down.

Even The Marina was exporting again, with 4,000 Ford Escorts and Cortinas sent annually to Britain. It was still considered a valuable part of Ford's European division. After all, when Ford of Europe had been formed in Cork in 1967, it was a merger between Ford of Britain, Ford Germany and Henry Ford & Sons, Ltd. In 1982, Ford even invested £10 million to ready the plant for production of the new Sierra. The inefficiencies of The Marina and the CKD program in general were plain to see when looking at the numbers of cars it produced in relation to other Ford factories. According to Miriam Nyhan's book on The Marina, Are You Still Below?, in 1983, the Genk plant in Belgium was churning out 1,300 Sierras a day. Dagenham, in England, was building 1,000. Cork, just 80.

The Marina shut its doors for the last time after 67 years in July, 1984. The factory's tire supplier, Dunlop, located nearby, closed-down too with a loss between them of over 1,800 jobs, which may not sound like much, but, in a city the size of Cork, it helped drive unemployment up by 21%. It was a blow from which it would take the city over a decade to recover as guys, many of whom had worked at the plant for 35 or 40 years, struggled to find work amidst the recession.

The last Irish-assembled car, a Mazda 323, rolled off the line towards the end of 1984 at the Motor Distributors Limited plant in Dublin— a plant that had originally built cars for Volkswagen, Goggomobil and Mercedes. In 1983 and '84, the operations of Daihatsu, Datsun, Fiat, Ford, Mazda, Renault and Toyota shut up shop leading to the loss of 12,000 jobs nationally and significantly contributing to the 1980s depression in which Ireland found itself.

What Ireland got in return in the ensuing years, thanks to globalism and freer markets, was an in-rush of foreign tech, among other new businesses. In the late-Eighties, for example, chip-maker Intel decided to set-up its European manufacturing facility west of Dublin. Hewlett Packard opened-up nearby and Dell had a plant in Limerick. How about Cork, the city nearly wiped-out by the closures of Ford and Dunlop? Today, in addition to Apple's plant and European headquarters, the city and surrounding area produces 45 percent of the world's Tic Tacs and almost all of its Viagra.

Those plants and tech companies were largely responsible for the stratospheric performance of Ireland's economy in the 1990s and 2000s, which helped drag the country, for better and worse, into a more liberal modernity. But before all that, don't forget the cars. So the next time the doctor prescribes you those little blue pills, also pour one out for the Irish motor assembly industry. I always do.