In 1962, A Lost U-2 Spy Plane Nearly Triggered World War III

In October 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis threatened to escalate into global thermonuclear war. The United States and Soviet Union both mobilized over nuclear missiles in Cuba, and a single spark could have effectively ended civilization. But what's not well-remembered today is that at the height of that dispute, a lost plane near the North Pole nearly led the world down the same path.

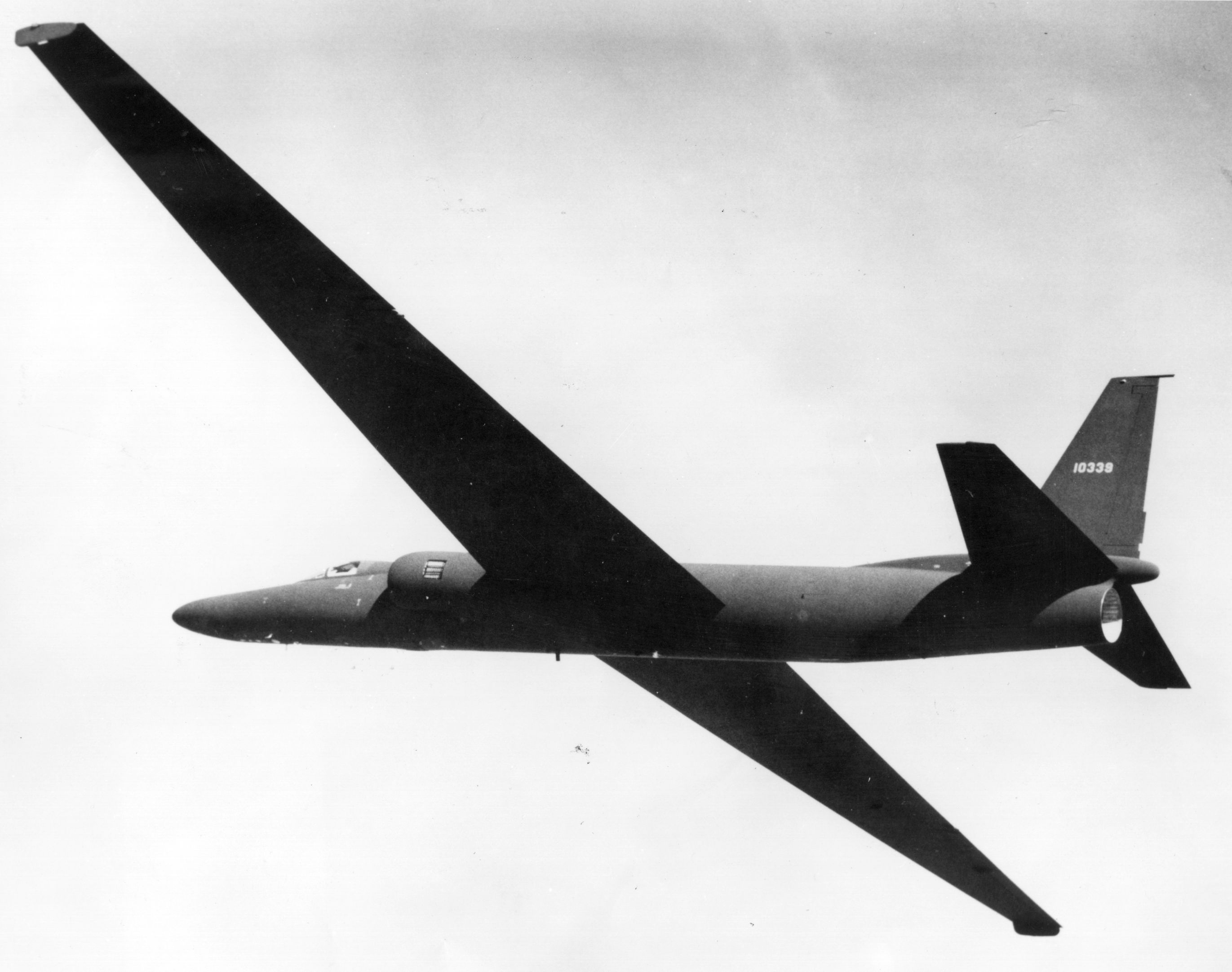

On October 4, 1962 a U-S spy plane on a reconnaissance flight over Cuba made a disturbing find: Soviet SS-4 short-range ballistic missiles and SS-5 intermediate range ballistic missiles. Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev had jumped at Cuban leader Fidel Castro's offer to host missiles in his country, just a few hundred miles from America—and within easy launch range.

A furious Washington ordered the U.S. Navy to blockade the island country, technically an act of war, and prepared both an invasion force and its nuclear forces—just in case. U.S. forces worldwide were at DEFCON 2, just one step below imminent nuclear war.

On October 27, as U.S. intelligence attempted to assess the construction of missile facilities, a U-2 piloted by Air Force Major Rudolph Anderson was shot down over Cuba. The shootdown prompted Assistant Secretary of Defense to state, "(The Soviets) have fired the first shot."

What decision makers at the time did not know was that there was a very, very good chance of a second shot—one that might have triggered all-out war.

As the U.S. intelligence community put Cuba under a microscope, other reconnaissance operations against the Soviet Union continued as normal. Also on the October 27th, a U-2 piloted by Captain Charles Maultsby took off from Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska.

Maultsby was headed to the North Pole region, where he would collect air samples that could inform about Soviet nuclear tests north of the Arctic Circle.

GPS had not been invented yet and Maultsby was too far north to rely on ground navigation systems, so the pilot navigated reading the stars. Unfortunately, in part due to the Northern Lights, Maultsby got lost and started heading in the wrong direction: into Soviet airspace.

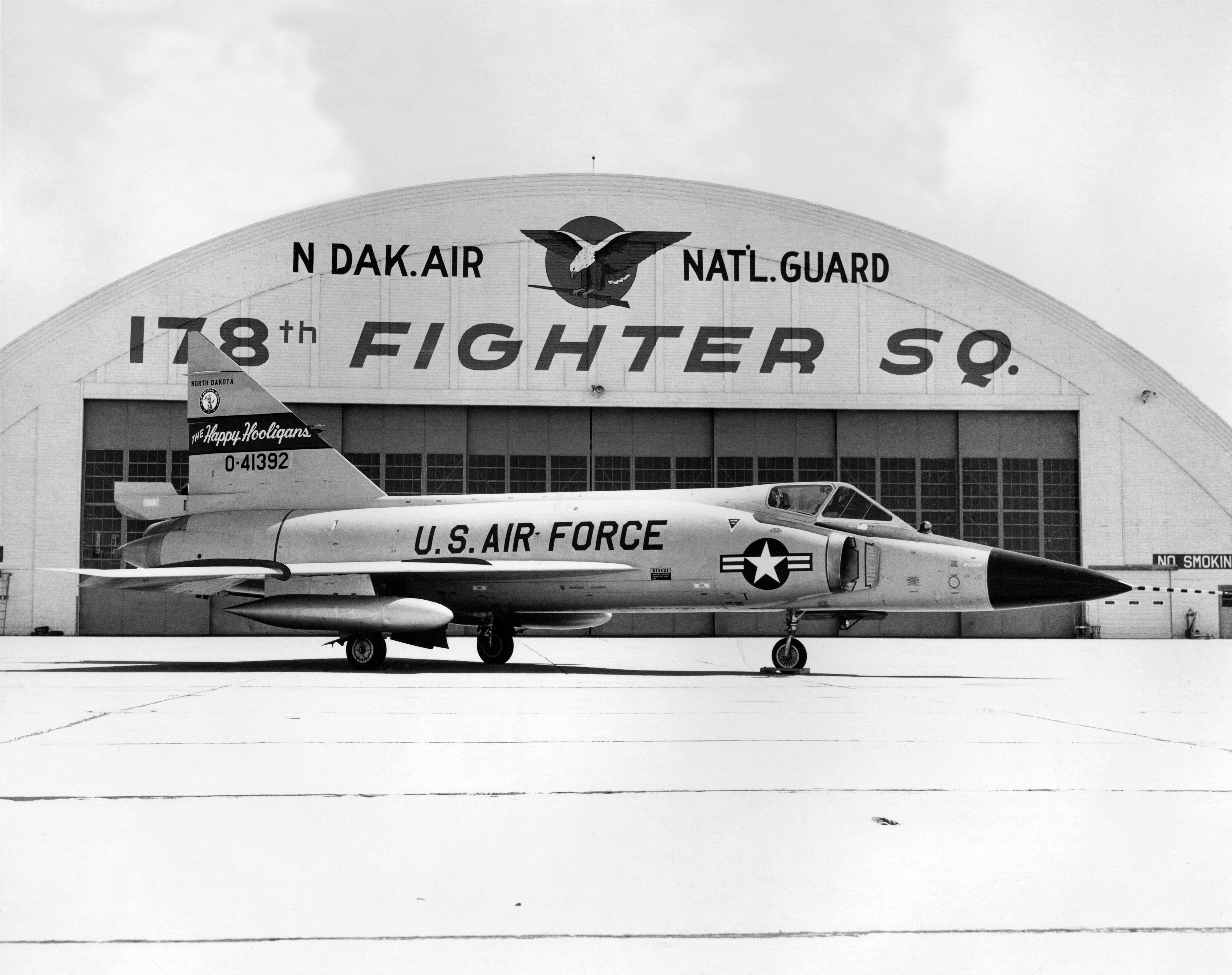

The Soviet air defense command, PVO Strany, detected the U-2 and scrambled MiG-19 fighters to intercept. At the same time, the U.S. Air Force scrambled a pair of F-102 Delta Dagger fighters to protect the U-2 and bring Maultsby home. The fighters typically carried Falcon air-to-air missiles, and their wartime mission was to shoot down incoming nuclear-armed Soviet bombers. One very concerning detail: once the Pentagon shifted alert status to DEFCON 3, the Delta Daggers' conventionally armed missiles had been swapped out with nuclear ones. Once equipped with the missiles, the pilots could launch them and their nuclear warheads at will.

(The AIM-26A Falcon was armed with the W-54 nuclear warhead. The W-54 also armed the Army's Davy Crockett battlefield nuclear weapon, seen here at a test attended by Robert F. Kennedy. The W-54 had an explosive yield the equivalent of .25 kilotons, or 250 tons of TNT. Hiroshima, by comparison, had an explosive yield of 16 kilotons.)

What happened next? Obviously, you and I are here, so it was resolved peacefully. It is however very easy to imagine an alternate outcome where we are not.

The F-102 pilots were ordered to defend the U-2 from Soviet fighters, but had only nuclear weapons to carry out their mission. Had they indeed launched at their Soviet counterparts, Moscow would have almost certainly would have interpreted it as the first moves of an all-out nuclear war. Their worst fears confirmed, the Soviet leadership could have ordered a first strike to destroy as many American nukes on the ground as possible. A key part of this strike would have been the launch of missiles in Cuba against targets such as Washington D.C. and New York, with retaliatory strikes turning the island country into a radioactive ruin.

Alternately, if Captain Maultsby had been shot down or crashed and presumed shot down, the U.S. government could have considered that the "second shot" and an attempt to blind U.S. intelligence before an all-out attack. Again, the pressure to use nuclear weapons before they were destroyed by surprise attack would have been overwhelming.

For America, tensions between both Russia and China right now feel more severe than they have in a long time. But at least electioneering and trade wars aren't nuclear holocaust, though the powers that be must never forget how close we can get to that—and how close we've come relatively recently.

For more information on the incident, watch Mark Felton Productions' latest mini-documentary above find out more. There's also this extended piece on the incident Vanity Fair published in 2008 that's definitely worth a read.