I'm So Sad To Say That Bruce Meyers, The Man Who Created The Dune Buggy Industry, Is Dead At 94

I've realized that I sort of have a type when it comes to people I hold as personal heroes. They tend to be mechanically-minded tinkerer/artists, people like Alexander Calder or Rebecca Horn or my friend Tom Jennings. They don't necessarily take themselves too seriously, but they do meaningful work. There's another big one on that list, someone I've admired for years: Bruce Meyers, the man who pretty much singlehandedly started the whole wonderful industry of Volkswagen-based kit cars and dune buggies. He died today, at his home in Valley Center, California.

Bruce was best known for the car that bears his name, the Meyers Manx, which is, I think, an absolute icon of automotive design, still the image that pops into everyone's mind when they hear the words "dune buggy."

People in Southern California had been hacking together "dune buggy"-like vehicles from old Jeeps and stripped-down cars for years, and once the Volkswagen Beetle began to gain popularity in America in the 1950s, the sort of people that liked to drive in piles of sand began to notice that the light little car had surprisingly good traction, was tough, and the body was easy to remove, all great qualities for a little off-roader.

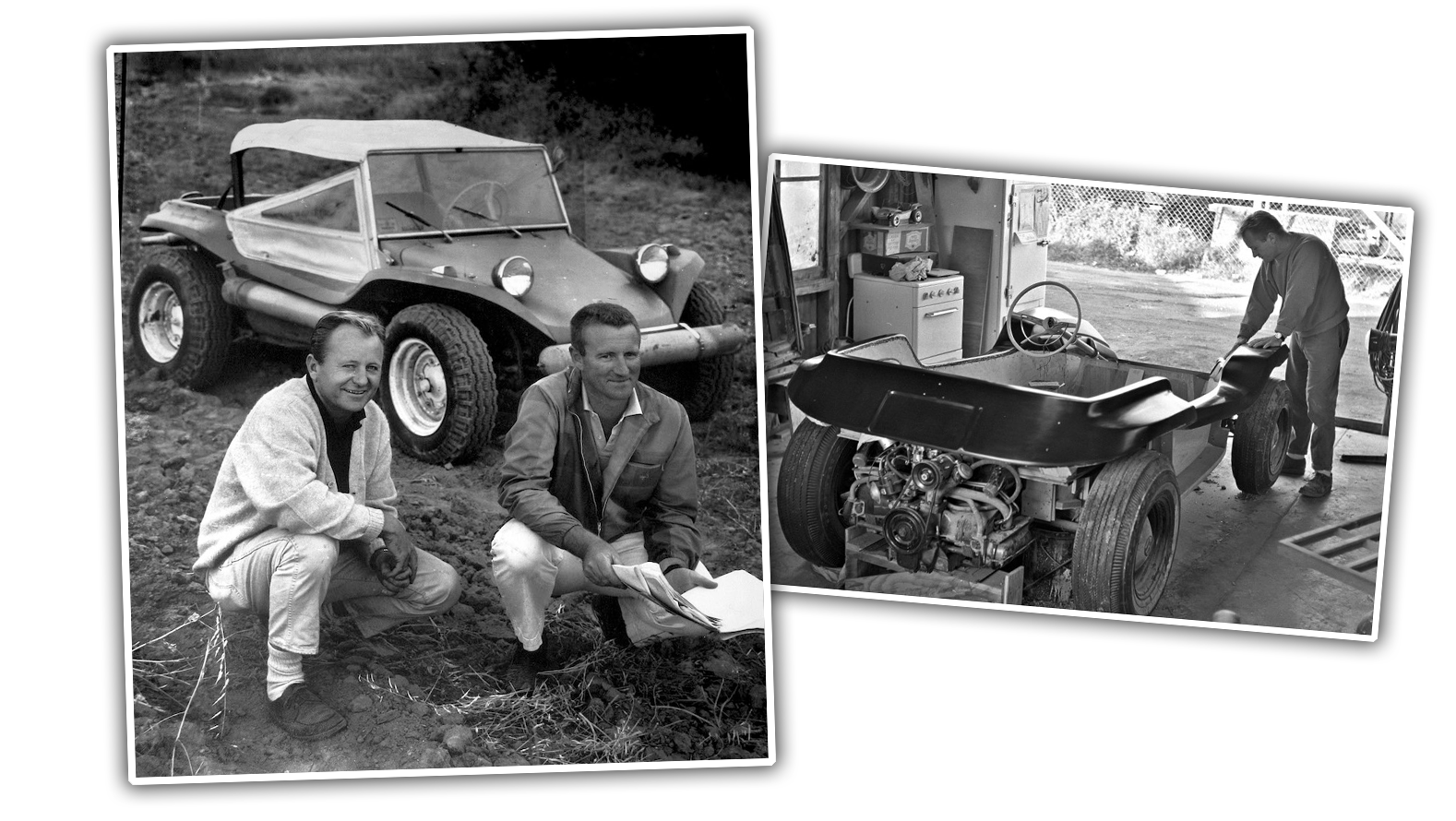

People began stripping Beetles down for off-road use, and Bruce noticed this in the early '60s. Bruce wasn't just content yanking the fenders off a Bug and calling it a day; Bruce was an actual, no-joke artist, and he had been building fiberglass boats for Jensen Marine, a combination that led to the formula that would make him famous: a wonderfully-designed fiberglass body that could bolt right on to a (shortened) Beetle chassis.

The first version of Bruce's idea, built in 1964, was a bit different than the later production ones that would come to be called Manxes, after the tail-free cats, in that it was more of a unibody design, with hard points to bolt the Volkswagen axles and drivetrain but no need for the pan.

That first Manx, with green add-on fuel tanks made from re-purposed welding gas tanks, was known as Old Red, made a record-setting off-road run from Tijuana to La Paz, a run that would inspire the famous Baja 1000 off-road race that's still run today.

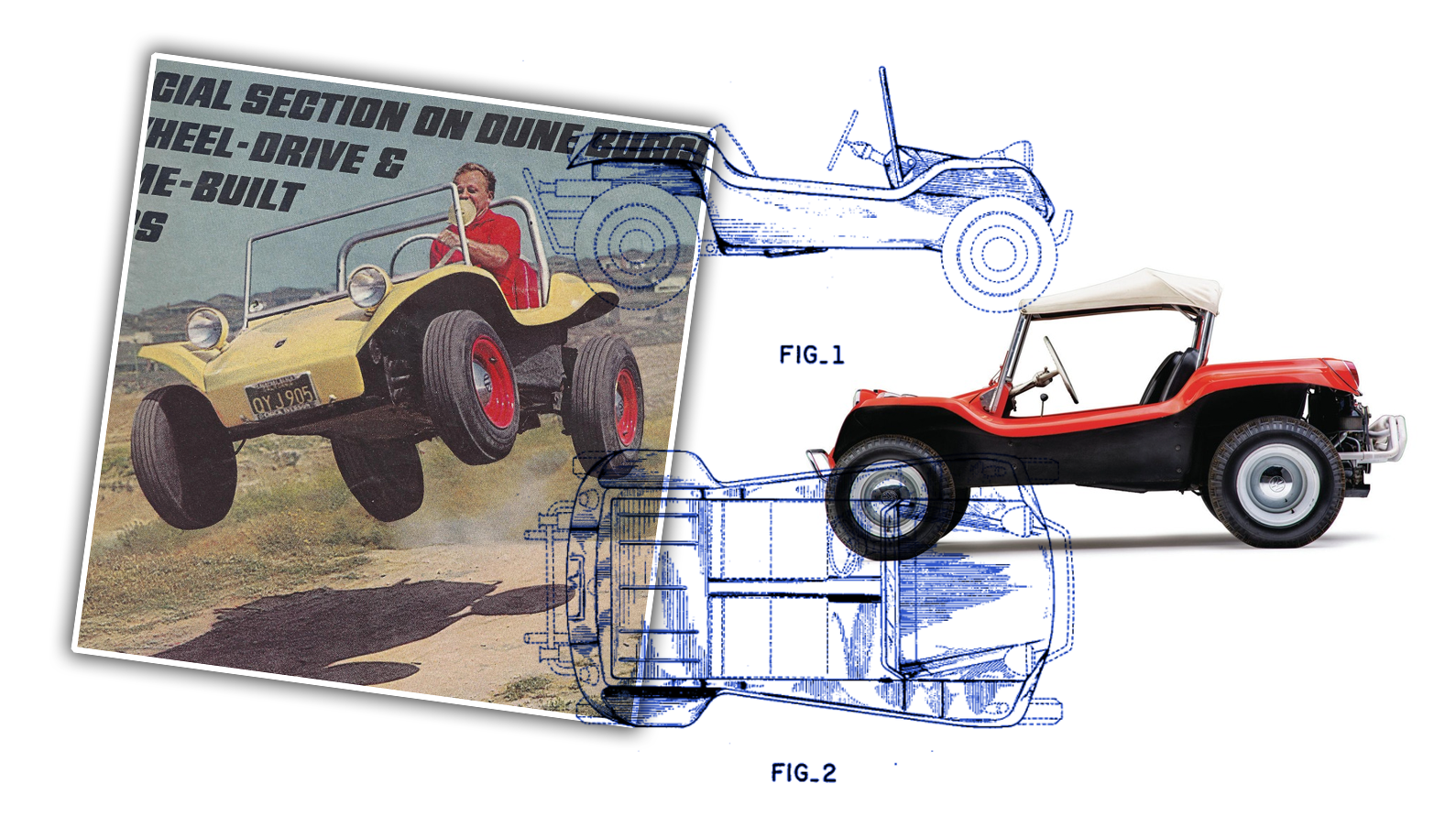

Let's just take a moment here and look at the Meyers Manx, because it's one of those designs that's so woven into our cultural automotive consciousness that it can be hard to think of objectively.

Given the limitations of the requirements for the Manx—tough, cheap, easy to put together in a backyard with basic tools—the result is, I believe, and absolute design triumph.

The body is one basic tub that incorporates pretty much everything—you just bolt on a windshield, lights, and a roll bar and you're good to go, pretty much. For the era, it was a completely up-to-date design, a completely different design direction from the 1930s Beetle design, and with its almost-catenary curved fenders that form the overall shape feels like an Eero Saarinen architectural work, just on a much smaller scale.

Meyers described the Manx in an interview:

I'm an artist and I wanted to bring a sense of movement and gesture to the Man. Dune buggies have a message: fun. They're playful to drive and should look like it. Nothing did at the time. So I looked at it and took care of the knowns. The top of the front fenders had to be flat to hold a couple of beers, the sides had to come up high enough to keep the mud and sand out of your eyes, it had to be compatible with Beetle mechanicals and you had to be able to build it yourself. Then I added all the line and feminine form and Mickey Mouse adventure I could."

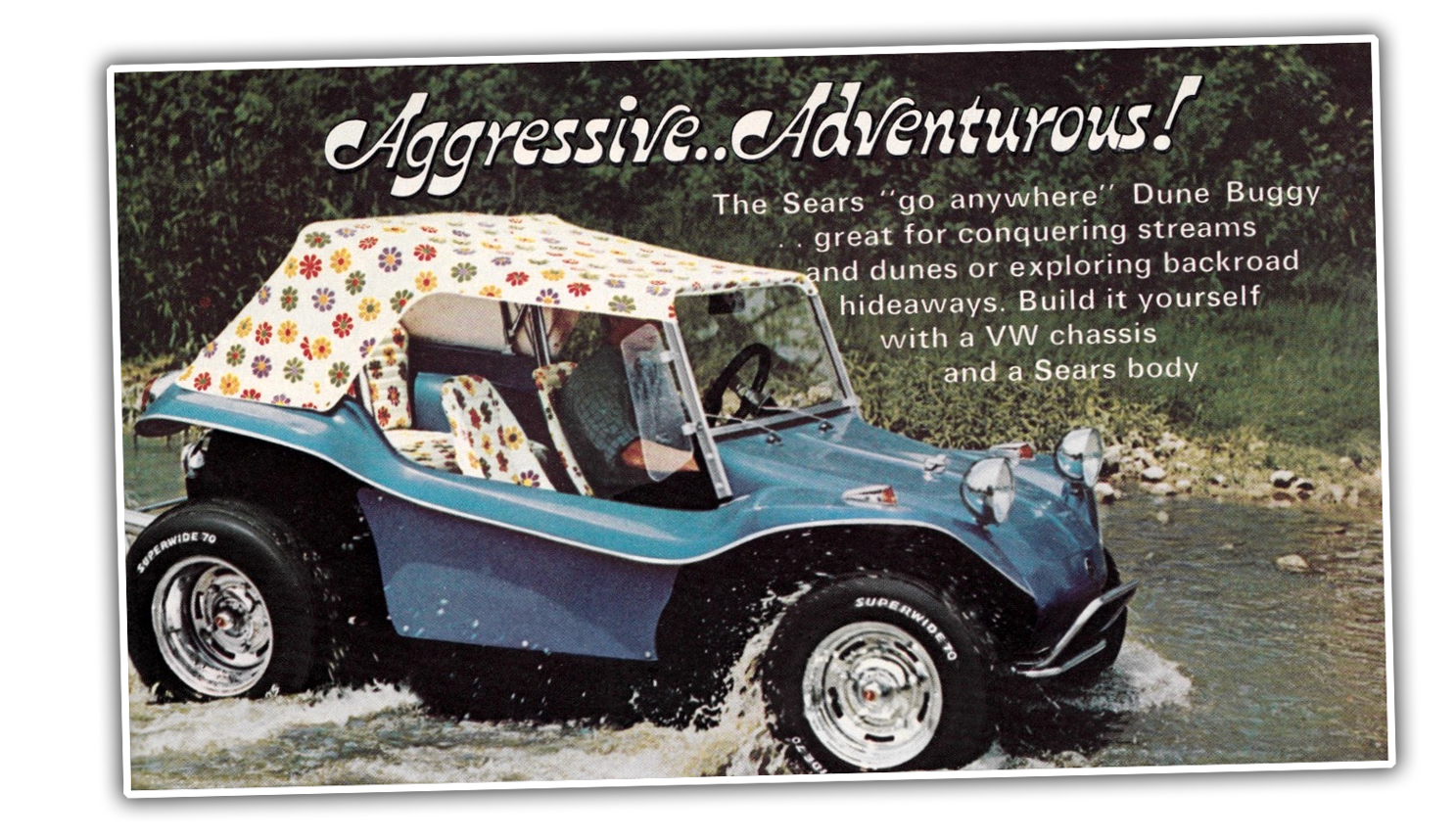

The result was absolutely perfect for what it needed to be, perhaps too perfect, because it was imitated almost immediately, mercilessly and unrelentingly.

Everyone, even upstanding cornerstones of American commerce like Sears, were cranking out and selling shameless Manx-clones, and despite holding a design patent, Meyers was unlucky in court, and the flood of knockoffs ended up putting him out of business in 1971.

Bruce bounced back, inventing the fiberglass hot tub, and later in life getting back into building Manxes.

I got to meet Bruce a few years ago, when I was driving a Class 11 desert racing Beetle; he was warm and kind and we talked at painful length about all kinds of Volkswagen and dune buggy ephemera. He was so sharp and warm, and it was hard to reconcile that this was an actual human being who had created this thing that seemed like it must have somehow always existed.

The Manx dune buggy design was so iconic to me that meeting Bruce had the same sort of surreal effect that you would feel if you were introduced to the person that invented that feeling you get after a long fun day at the beach with friends, when you're young and beautiful and a bit sunburned and your hair feels thick and salty and the sunset is making the inside of your car shades of vivid orange and everything feels wonderful in the world.

It'd be like meeting that person. Only all of that feeling is a car.

Bruce Meyers I think doesn't often get the recognition he deserves as a car designer; he gets recognized sure—his first Manx is on the National Historic Vehicle Register, after all—but I think his achievement puts him among more recognized auto designers like Virgil Exner or Gordon Buehrig.

He designed a car that sparked a whole new class of vehicle, a whole sub-industry; how many car designers can say that?

Bruce Meyers showed the world how much fun cars could be, then put the ability to actually build those cars into the hands of any one with a few free weekends and a ratty old Volkswagen. His Manx was free of pretension or foolish status or posturing—it was simple and fun, and a gift to everyone who loves the sensation of being in motion.

Bruce remains one of my automotive heroes, and he'll be missed.