I Read The Men Because Of Its Hilarious Name And Walked Away With A Whole New Take On Vintage F1

Not every racing book will change your perspective. The Men will.

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

There's something about motorsport that makes it a difficult thing to capture in words, and that's especially true when it comes to nonfiction books written by motorsport journalists. Sometimes, you strike gold, but most of the time, a broadcasting voice or recap-ready wit just aren't cut out for a book. But Barrie Gill was firmly a part of the former camp when he penned 1968's The Men, a brief nonfiction book about the drivers competing in F1 in the mid- to late 1960s.

(Welcome back to the Jalopnik Race Car Book Club, where we all get together to read books about racing and you send in all your spicy hot takes. In honor of being trapped indoors, I've made the reading a little more frequent; every two weeks instead of every month. This week, we're looking at The Men by Barrie Gill, a then-current look at the mid- to late-1960s F1 scene.)

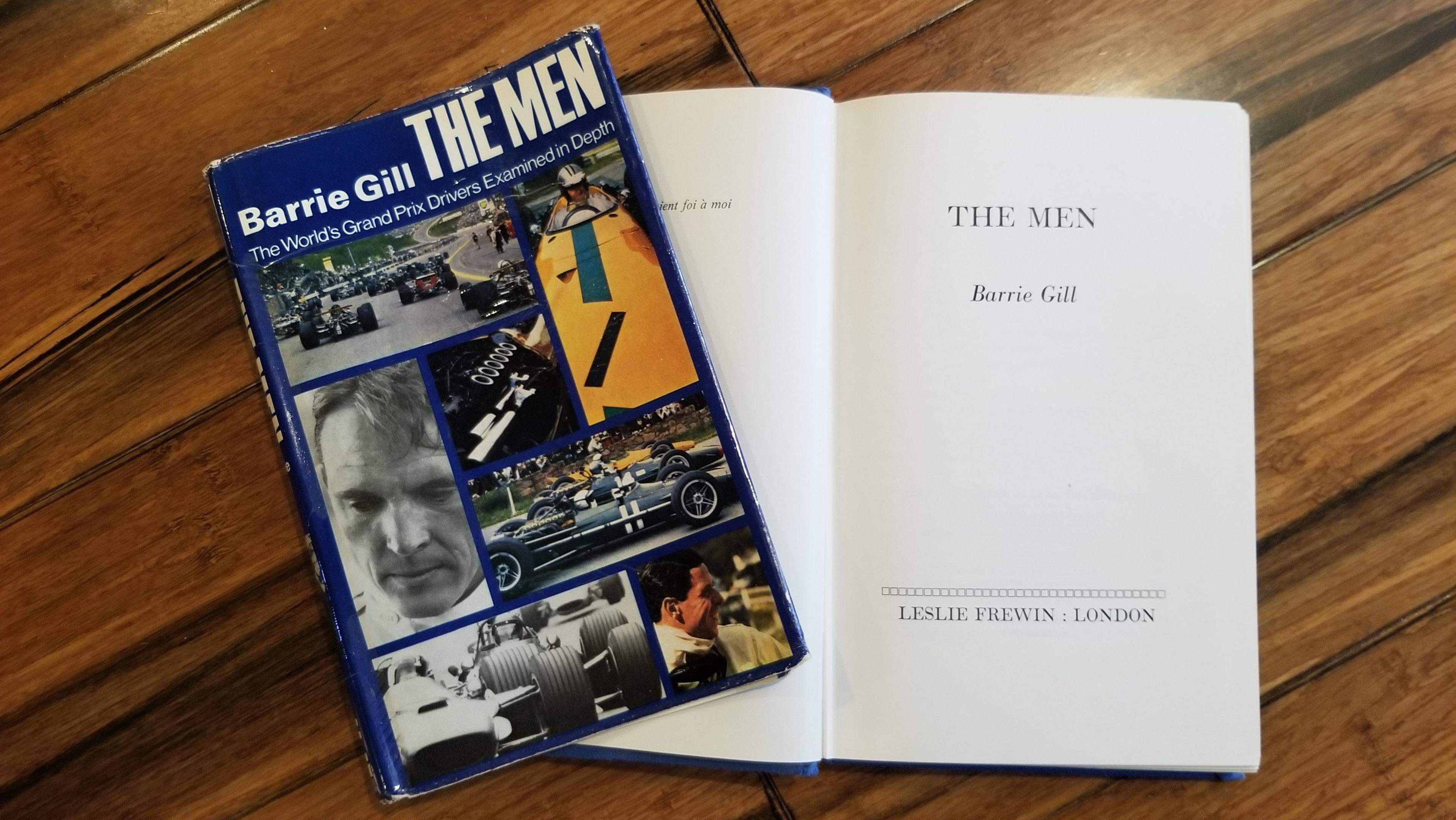

A kind soul that read my François Cevert blog earlier this year reached out to offer me some old racing books he was getting rid of; he said he'd rather they go to a good home all at once than have to worry about selling them on eBay. He wouldn't accept payment and only humbly accepted my thanks — but among this pile was one title that stuck out to me: The Men.

I'll admit it; I laughed out loud. The Men — often followed by a trademark symbol — is how I refer to the male trolls that like to send me bitchy comments and emails. So I set The Men aside with the intention of reading it first.

Here, though, is a book you can't judge by its title. This is a genuine masterpiece of motorsport literature. Through general descriptions of the atmosphere and short biographies of the racers in the mid- to late-1960s F1 scene, Gill paints a beautiful picture of a bygone era in motorsport, one that we tend to look back upon with both awe and shame.

Gill notes in the introduction that the book took him several years to publish because, just as he was preparing to send it to his publisher, several of the book's subjects died: Lorenzo Bandini, Jim Clark, Mike Spence, and Ludovico Scarfiotti. He needed help to begin the monumental task of rewriting the book, which I can tell you isn't easy. And I've never had to undertake a rewrite due to the fact that its subjects — people who I spent ample amounts of time with and truly cared about — were killed.

There's a certain heartache to The Men that comes from the fact that Gill is writing firmly in his era. When he projects that Bruce McLaren will soon give up driving to instead focus on becoming a business mogul, he doesn't know that McLaren will be dead before he has the chance. When he wishes the best for Dan Gurney's Anglo-American Racers team and the American driver's effort to bring more American drivers into F1, he doesn't know that Gurney will remain one of the few American drivers to ever enter the sport, let alone win a race.

I read a lot of biographies, and I've read a lot of multi-biography collections, but what stands out about The Men is the fact that the stories of these drivers are told in the present tense. This isn't Sid Watkins looking back on Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost — two drivers whose legend is well-known — or someone recounting an entire career with its ending already in mind. The Men is a moment in time. We learn about Jack Brabham and Bruce McLaren, whose storied careers have been transformed into countless books and documentaries, but we also learn about Jacky Ickx and Jo Siffert, men whose tales were kept closer to their chests.

I think that really helps to paint a strong picture of the era. Yes, many of these drivers had ties with racing — Ickx's father was a racing journalist, Jackie Stewart's brother competed in motorsport, Bruce McLaren's dad and uncles were masters of two wheels — but their parents generally weren't the multi-millionaires we see in F1 today. Chris Amon's family, for example, farmed. Jackie Stewart's owned an auto repair shop. Graham Hill didn't even drive a car until he was in his mid-20s, let alone think of racing one.

In Dan Gurney's section, Gill recounts the American racer noting that he wanted to race in Europe as opposed to America because, in Europe, there was a sense of care, tradition and engineering prowess that meant not everybody could participate, which he contrasted with the run-what-you-brung attitude of American oval tracks.

But there still was a chance for just about anyone to compete in European open-wheel road racing. Gurney was racing with Ferrari before he'd competed in 25 total events. Jo Siffert went from skipping school to pick and sell flowers to feed his family to racing F1. I won't say that every family of an F1 driver at the time was blue-collar, but they certainly weren't the industry moguls we see in Lawrence Stroll or Dmitry Mazepin today.

It gave me a different perspective on motorsport at the time than I had before. It's been clear to me and most other F1 historians that the 1960s and 1970s were when the sport really started changing, but where I've always been inclined to peg that mostly on safety and technology, I started to realize the economic aspect as well. In one part of The Men, Gill recounts Jackie Stewart joking about how he wanted to become a millionaire by age 30 — something that was, at the time, frankly unheard of for F1 drivers.

But that quote is indicative of the shift taking place at the time, where F1 had gone from being a pastime where you could make a few extra dollars to a lucrative career opportunity that would launch you into superstardom. This was the era where it happened. This was the era where F1 skyrocketed out of the grasp of the pretty-well-off to the extremely wealthy. Had Jackie Stewart come along 10 years later, he likely wouldn't have had the opportunity to race in F1 because he didn't come from a family of massive budgets, nor did he have a storied background in racing as a child. And yet, he was one of the figures that saw those conditions come into being.

It's not often that a motorsport book makes me rethink the way I've always understood the sport, but the broad scope of The Men painted a picture I'd never seen before: one of a world in flux that doesn't realize it's in flux; one of a dying yet rapidly blossoming era that would set the groundwork for years to come. I don't even think that was Gill's intention; he simply couldn't have known the importance of his era at the time of publishing unless he'd had a crystal ball. The best books, though, are the ones that you can return to time and again and walk away with something new. And I know I'll be doing that with The Men.

And that's all we have for this week's Jalopnik Race Car Book Club! Make sure you tune in again on December 6, 2021. We're going to be reading Grand Prix by Manning Lee Stokes. And don't forget to drop those hot takes (and recommendations) in the comments or at eblackstock [at] jalopnik [dot] com!