I Put 2,300 Miles On A New Honda Gold Wing And Now I Dig Dual-Clutch Motorcycles

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The Honda Gold Wing has a reputation as an old rider's bike, a plush and ponderous road couch for those who've finally unbent their beat-up bodies and settled onto something more accommodating to creaky knees and sore backs. But that doesn't mean you have to be one step away from a rocking chair to appreciate it. Though it may help.

At only a few years shy of 70, and with half a century of riding behind me, I have no qualms about including myself in that group of riders looking for a little comfort. At this point, anything that makes riding easier and more convenient gets my vote, so when I saw Honda had not only updated the Gold Wing by making it smaller, lighter, and sportier, but also by making the company's dual-clutch transmission (DCT) an option, I had to try one.

(Full Disclosure: Honda loaned me a Gold Wing to road test for a big, long road trip.)

I've owned two Gold Wings, a 1984 GL1200 and a 2003 GL1800. I can't recall why I sold the 1200, but I know exactly why the 1800 went away. On the open road it effortlessly put hundreds of miles per day in the mirrors while I lounged in a pillowy seat behind a barn-door fairing. But the rest of the time—around town, in parking lots, or in the garage—it was just too damn big and heavy. Eventually, no matter where I rode, I felt like a Fremen on a sandworm. I replaced the 'Wing with an 865 Bonneville, and wasn't that sorry to see it go.

A Slightly Sleeker ’Wing

My first impression of the new GL1800BD was echoed by nearly everyone who saw it. "That's a Gold Wing? It looks so... small."

At a claimed 800 pounds it's no lightweight, though it is about 80 pounds lighter than its predecessor. The lack of a trunk (currently only Gold Wing Tour models come with trunks) has a lot to do with the bike's slimmer appearance. The fairing, too, is narrower than the old one, and the angular styling makes the new Wing appear sleeker and less massive than its orca-like predecessor.

The Gold Wing's transformation was in part a result of a problem that's been plaguing another manufacturer of big touring bikes, Harley-Davidson. The riders who make up H-D's longtime customer base are getting older and dropping out of the hobby, and there are fewer younger riders stepping up to take their place.

Honda, with its broad range of bikes in contrast to Harley's anything-you-want-as-long-as-it's-a-big-V-twin line-up, nevertheless had a similar problem with the Gold Wing, and the solution was to make it more appealing to a younger demographic.

That appeal begins with the smoothly beating heart of the B (base model) D (dual-clutch transmission) Gold Wings: a liquid-cooled, horizontally-opposed flat six. Aside from a handful of fasteners, every part in it is new compared to the previous generation's engine. Aluminum cylinder sleeves in place of iron liners reduce weight, and allow the bores to be closer together for a more compact engine. The crankshaft is made of a stronger material than before and it's lighter, more compact, and more rigid.

Weight is further reduced by Honda's Unicam valvetrain, which uses a single camshaft to operate each cylinder's two intake valves via finger rockers between the intake lobe and the valve stem, and the two exhausts via roller rocker arms. An ISG (integrated starter/generator) combines two heavy components into one lighter one.

The six cylinders are fed by a single 50 mm throttle body, and the intake-manifold volume has been reduced by 10 percent for more direct airflow and sharper throttle response. As a result of these and other weight-saving measures, the DCT-paired engine is a claimed 8.4 pounds lighter than the previous model's manual-transmission powerplant.

Honda has a long history of making "because we can, that's why" bikes like the six-cylinder CBX and the CX500 Turbo. The need for either of them was questionable, but they showcased what the company could do in a time when the "Universal Japanese motorcycle" (UJM) bike design was the norm.

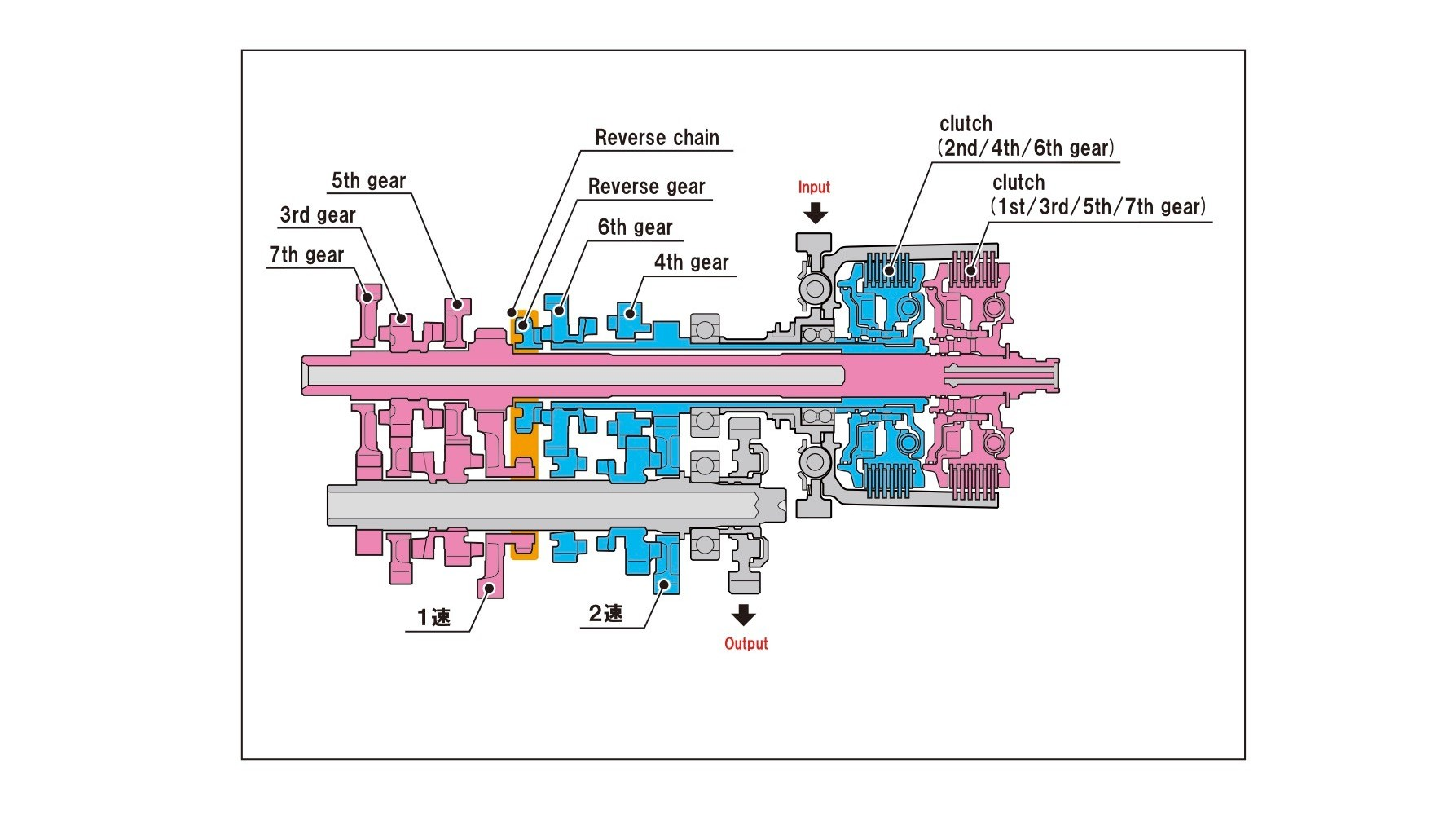

In making a seven-speed DCT optional on the Gold Wing, Honda is firing another shot across the bow of the industry, showing not only what it can do but possibly pointing the way for the future of motorcycling.

A Dual-Clutch You Don’t Have To Shift

DCT is a manual automatic or an automatic manual, take your pick. There is no clutch lever on the handlebar, nor is there a shift pedal (unless you order the optional foot-shifter kit my loaner came with).

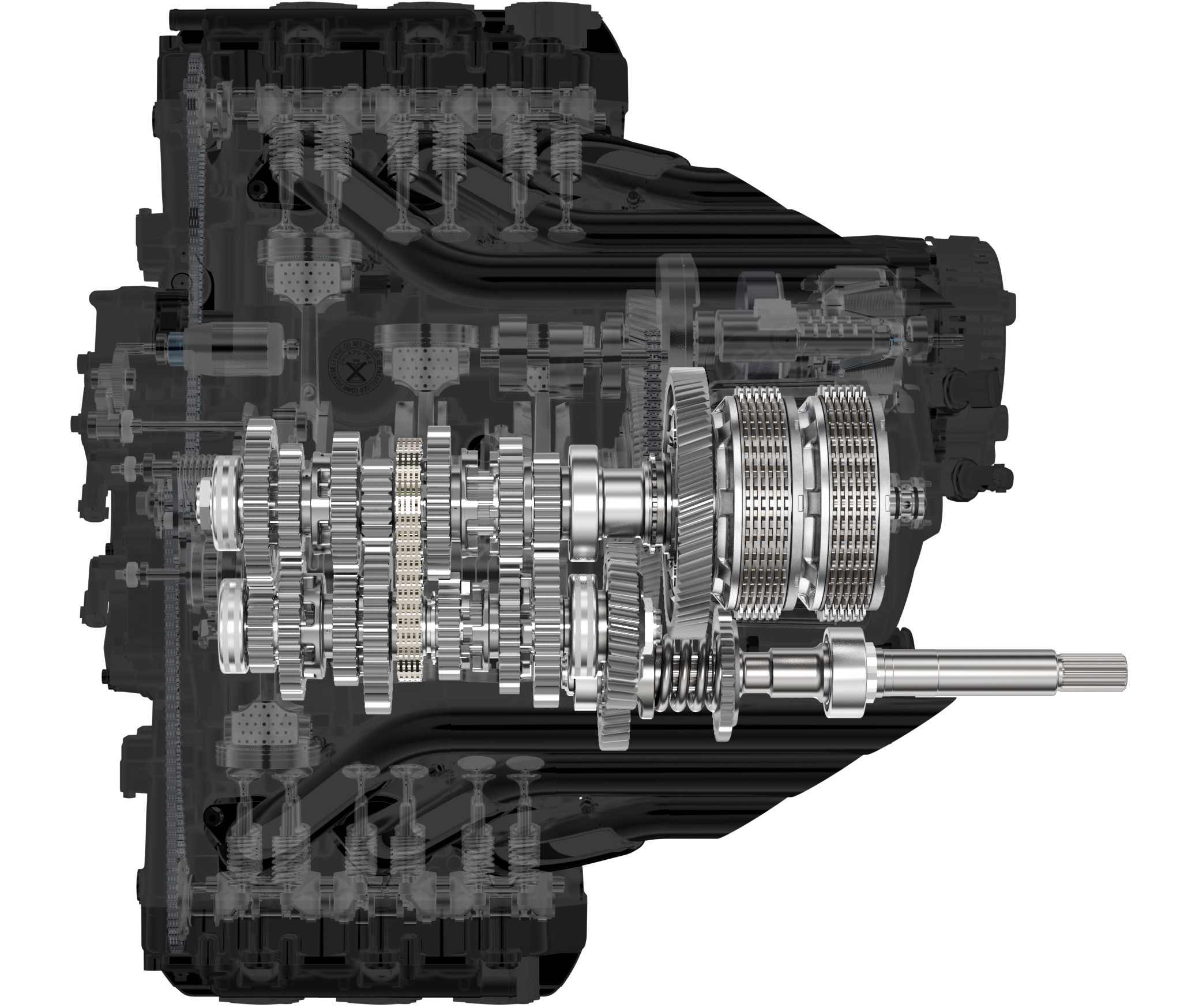

There are two wet multi-plate clutches in the back of the engine, placed one in front of the other. One controls even-numbered gears, the other odd-numbered gears. When one clutch is engaged the other is disengaged; they alternate with every gear change. The hydraulically activated changes are quick and virtually seamless and can be made with the throttle wide open. Because DCT uses multi-plate clutches like a manual-shift bike, rolling off the gas produces useful engine braking, unlike the automatic in a car or the CVT (constantly variable transmission) in a scooter.

Honda's DCT has two shift modes, Drive and Manual. In Drive it shifts like the automatic transmission in a car, although you can override it at any time (and in either shift mode) with small paddles on the left handlebar's switch cluster to shift up or down, after which it returns to Drive mode. I rode the Gold Wing for 2,300 miles during the time I had it, 95 percent of it in Drive. If there's a downside to letting a 125-horsepower engine with 126 foot-pounds of torque decide for itself when to shift, I didn't find it in any of those miles. When I wanted to pass a truck I just thumbed it down one or two gears, made the move, and let Drive take over again.

Manual mode lets you decide when to upshift. Unlike Drive, which makes its way to top gear quickly, Manual lets you hold a gear all the way to—and even past—redline (sorry, Honda, but I had to find out). In this mode, you shift up and down as needed as if you were riding a manual-transmission bike, and the only time the DCT overrules you is if you slow down enough in a given gear to lug the engine. At that point, the DCT reverts momentarily to Drive mode, downshifts, then returns control to you when the gear and the engine revs match up. The only thing missing from DCT is a little smirk icon on the dashboard that lights up and says, I got this.

I rode the Gold Wing for 2,300 miles during the time I had it, 95 percent of it in Drive. If there's a downside to letting a 125-horsepower engine with 126 foot-pounds of torque decide for itself when to shift, I didn't find it in any of those miles.

In addition to the two shift modes, there are four ride modes: Tour, Sport, Economy, and Rain. Through the bike's throttle-by-wire system they modify the speed at which the throttle body opens, change the shift points, and in the case of Sport, make the braking a bit more aggressive. Tour is the one I used most, and it tended to upshift early and settle into seventh gear as soon as practical. Sport could easily be called Beast mode. Select it, and the Dr. Jekyll-ish engine goes full Mr. Hyde on your ass, snarling and spitting you from corner to corner, holding each gear a lot longer than the prudent Tour ever thought of doing, and generally making you suddenly very aware of the bike's size and weight. And not in a comforting way.

Sport is actually the Gold Wing's true personality, raw and unfiltered; the other three modes all tone it down in various ways. I found little use for Sport except passing long lines of cars and keeping myself wide-eyed between coffee stops.

Economy and Rain modes are pretty much what their names imply. Both soften the power delivery and throttle response and tailor the shift points to increase gas mileage or reduce the risk of losing traction on wet pavement. Because I live in Oregon I had several opportunities to use Rain, but I never got around to riding enough full tanks in Economy to see exactly how economical it was.

I never realized how much concentration shifting gears required until I got into some heavy urban traffic in an unfamiliar town and didn't have to do it. Honda initially expected DCT models to account for about 30 percent of GL1800 sales; the current reality is more like 70 percent. And it isn't just graybeard touring riders like me who prefer it. Shiftless models account for almost 50 percent of Africa Twin dual sport sales as well.

DCT isn't a gimmick, it's a useful and forward-looking technology that could trickle down the entire Honda range in time, helping attract the new riders the motorcycle industry desperately needs for its survival, many of whom have never had any experience with manual transmissions on bikes or in cars.

What Makes The ’Wing Smooth

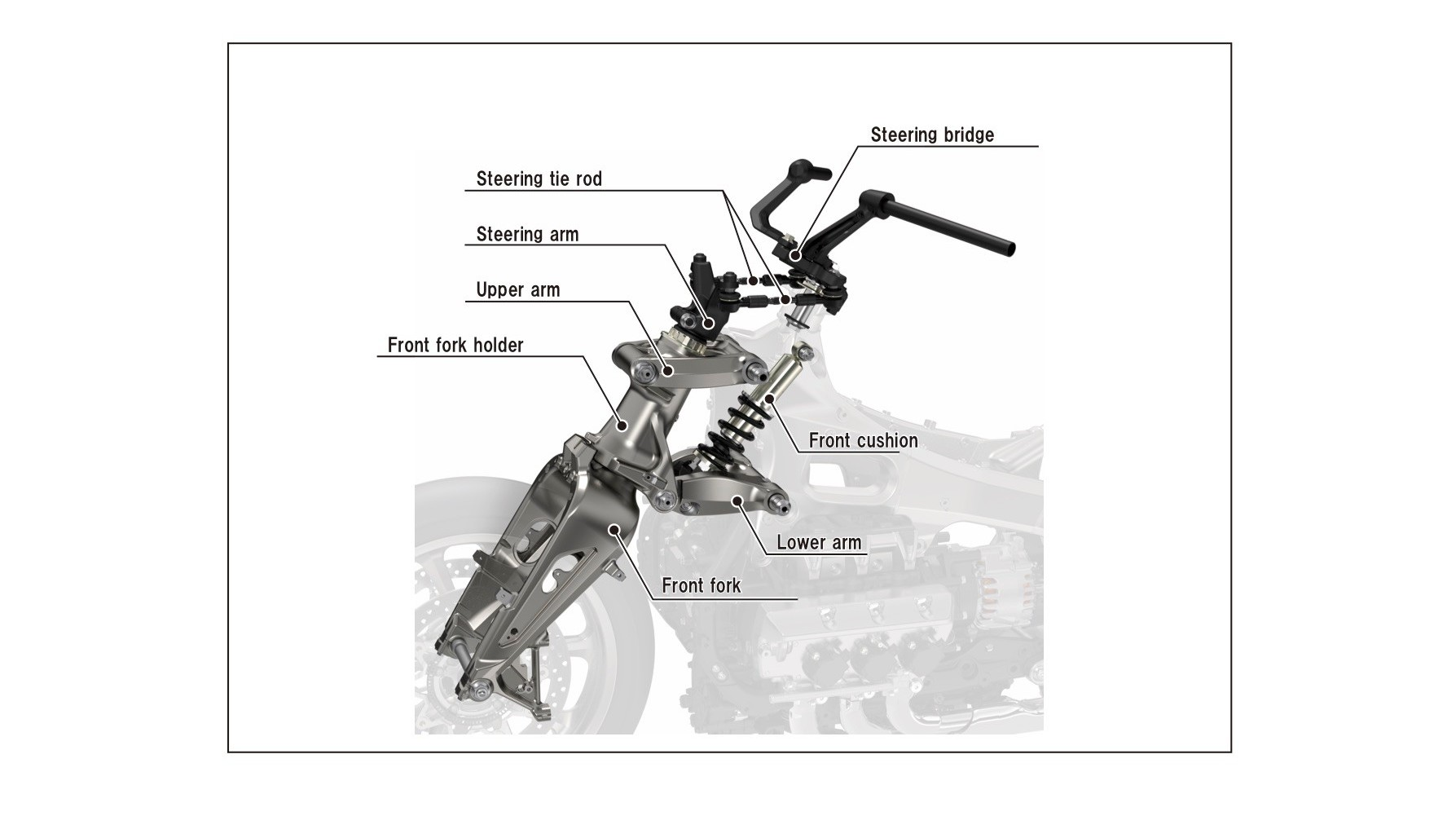

Another item on the Gold Wing's "because we can" list is the new double-wishbone front suspension. It resembles the fork developed in the 1970s by Norman Hossack and used later by BMW in its Duolever fork. But Honda would prefer you think of it simply as a double A-arm front suspension from a car (a Honda car, if you don't mind) turned 90 degrees and adapted to motorcycle use.

A stout, solid upright structure loops over the front wheel and is connected to a pair of wishbones that pivot vertically on the frame. At the forward end of the arms is a fork holder that acts like a steering head in which the upright turns. The handlebars turn on bearings in the frame and are connected to the upright via links with ball joints at both ends. Wheel movement is controlled by a single shock absorber attached to the lower wishbone on one end and the frame on the other.

This system removes most of the friction inherent in telescopic forks so there's less initial resistance to wheel movement when you hit a bump, and the double-wishbone design has inherent anti-dive properties that reduce the sudden forward weight transfer under braking typical of telescopic forks. The upright is extremely rigid, too, and doesn't flex like long, unsupported fork tubes can under cornering loads.

The double-wishbone design seems like overkill until you realize what other benefits it brings to the Gold Wing besides improved suspension compliance.

With a telescopic fork, the front wheel moves rearward as the forks compress, but the Wing's front wheel moves vertically through its travel. This means the engine can be placed farther forward in the frame without interference. This, in turn, allows the rider and passenger to sit closer to the front of the bike for better steering feel and weight distribution, and since this puts them closer to the fairing, the fairing can be smaller and still be as effective as a larger one placed farther away.

The smaller fairing produces less drag—a claimed 11 percent less compared to the previous GL1800's—which improves gas mileage, which means the gas tank can be smaller, taking up less of the limited space available inside the frame.

Stopping Power And Safety

The brakes on a bike that weighs half a ton with the average suitably attired rider aboard better be good and the Wing's triple discs are very good. The electronically controlled combined braking system spreads the load between both wheels, even if you apply only the lever or the pedal, and the standard ABS takes over if the circumstances require more than your own braking skills can provide. There's enough whoa-power on tap at the brake lever alone that I seldom used the rear pedal, and when I did the big Wing shed speed like a wet dog shaking off the rain.

A Gold Wing wouldn't be a Gold Wing without a suite of comfort and safety features. Cossetting you in luxury are, in no particular order, cruise control, a tire-pressure monitoring system, heated grips, an electronically adjustable windscreen, a navigation system, an audio system, a Smart Key fob, a TFT dash display that's visible even in bright sunlight, a parking brake, reverse and walking modes for maneuvering tricky parking spots or uneven ground at low speed, puddle lights on the fairing (presumably in case you drop the Smart Key fob at night and need help finding it), a vent on the top of the fairing behind the windscreen, Apple Car Play, and a handy storage bin in the top shelter.

Oddly, only the Canadian-market Gold Wings come with a tool kit. We Yanks are on our own if something breaks.

A Born Road Tripper

Honda originally sent me a zero-mile, new-in-the-crate 2019 Gold Wing, but it got into a fight with gravity during shipping and arrived looking very much the loser. A 2018 model was pulled from the demo fleet and sent in its place, complete with optional backrests for the rider and passenger, an accessory power plug, and a rear luggage rack. Thus armored against the uncertainties of the highway, I did what you're supposed to do on a touring bike—I toured, a four-day, 850-mile round-trip ride to a small town in Nevada next to the Black Rock Desert for an annual meet-up with some of my less-deranged friends in the Iron Butt Association.

Marketing research indicated that the riders Honda wanted to attract to the Gold Wing were more likely to take their bikes out for a weekend than two weeks. One by-product of this was the reduction of each saddlebag's luggage capacity to 30 liters, 10 liters less than the earlier models. The gear I usually carry on every tour—tools, a tire repair kit and pump, a first aid kit, extra gloves, face shield cleaner and cloth—all fit, but there was less room left over for things like a jacket liner and off-bike shoes. The Tour models' trunk can be added as an accessory if your priorities change down the line, but I took the easy route and strapped a duffle bag on the passenger seat, a dry bag with cold-weather gear on top of that, and set the alarm clock for an early departure.

Logging five or six hours a day on a motorcycle is a good way to get to know it in a short amount of time. I'd already fallen in love with the DCT, and a couple of hours from home I developed a similar affection for the seat. It's rare for me to keep a stock seat for much longer than it takes to get a custom seat maker on the phone, but the Gold Wing's suited me perfectly, and the optional backrest was just the ticket for my dodgy spine.

For 2018 the handlebars were moved slightly forward and the pegs slightly rearward for a sportier riding position that still felt office-chair perfect. At its highest position, the windscreen created a pocket of quiet, near-still air around me, while at its lowest it allowed a noisy rush of cooling breezes through my jacket and helmet vents. I plugged my electric vest into the accessory outlet, set the heated grips to high, and pointed the Wing toward Nevada, 400-ish miles distant.

Over the next four days, I came to appreciate and enjoy every feature of the bike except two. The in-dash navigation system is fine for casual users and will get you where you're going. More experienced GPS nerds will be frustrated by the slow and wonky input procedure that uses knobs and buttons instead of a touch screen, the lack of some features and menus that are included in many inexpensive stand-alone GPS receivers, and the fact that you can't adjust any of the settings when the bike is in motion. Apparently I can safely tune the radio, check and reset the trip meters, and toggle between readings on current and average gas mileage while doing 70 mph on the interstate, but I'll die in a flaming wreck if I try to zoom the GPS's screen magnification, which is accomplished by a simple turn of the knob on the central panel—but only when you're stopped.

The audio system comes with external speakers, but their output quality is at the mercy of wind noise and signal strength. You can jack your phone or MP3 player into the system through USB plugs in the saddlebags and the compartment in the top shelter—the plugs can also be used to charge devices—but the speakers remain problematic.

In a move to appeal to the younger, more tech-savvy riders the new Gold Wing is aimed at, the audio system is designed to work with Bluetooth helmet speakers. But the bike doesn't come with them, nor does Honda sell them as accessories. Advances in consumer electronics occur at a blistering pace, and Honda felt that rather than branding and warehousing Bluetooth headsets that would quickly be obsoleted, it was better to let riders choose their own from the aftermarket. Previous Gold Wings came with a built-in audio plug for hardwired headsets, a simple, cheap, and foolproof system. I'd like to have that back, Honda, please and thank you.

It seems strange, given what we know about its subsequent evolution, that the original Gold Wing, the 1975 GL1000 (another "because we can" volley), was supposed to be a sportbike. Now, 44 years later, the 2018 GL1800BD is returning to its sporty roots without losing the touring chops it acquired along the way. It's a potent and refined tool for touring, or carving up twisty two laners, or just bopping around town doing errands. And take my word for it, you don't have to be young to enjoy it, although you might feel that way after a run-up through the gears in Manual/Sport.

Jerry Smith's latest book, Missed Shifts, spans a career riding fast bikes and covering the motorcycle industry. You can get it on Amazon here.