How Women's Demand For Hairpins Led To One Of The Most Advanced Cars Of The 1950s

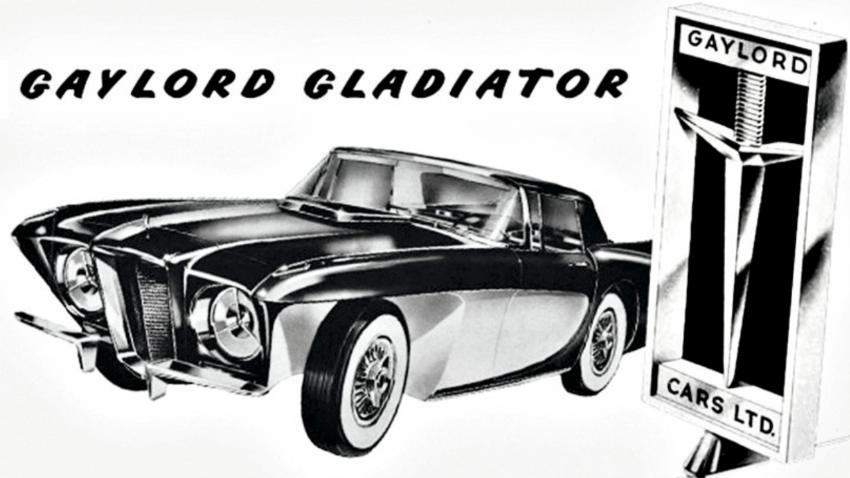

Styled by design-legend Brooks Stevens and outfitted with state-of-the-art features, the '57 Gladiator was billed as the "ultimate in personal transportation."

Last week I found myself in Friedrichshafen, the epicenter of German zeppelin innovation in the early 20th century. To support zeppelin development, an entire engineering industry sprouted up near that town on Lake Constance. So when two sons of a wealthy Chicago hairpin magnate began searching for a company to develop a ridiculously expensive custom car in the 1950s, Friedrichshafen stood out.

Setting Out To Build The Ultimate

The family's name was Gaylord, and the two brothers looking to design and build their own car were named Jim and Ed — heirs to a fortune that their father, Solomon H. Goldberg, had amassed via his hairpin empire in Chicago. Per a December 1955 Motor Trend article about the brothers' project, Jim said the goal, "Wasn't to be just another sports car, or even something better than that; it must be better than anything in the world for its purpose — the ultimate in personal transportation."

That's a hell of a goal.

The article also mentions that the car was "born with the proverbial silver spoon in its grille" and that it "has had every advantage that money can provide." This was definitely the case.

Building A Hairpin Fortune

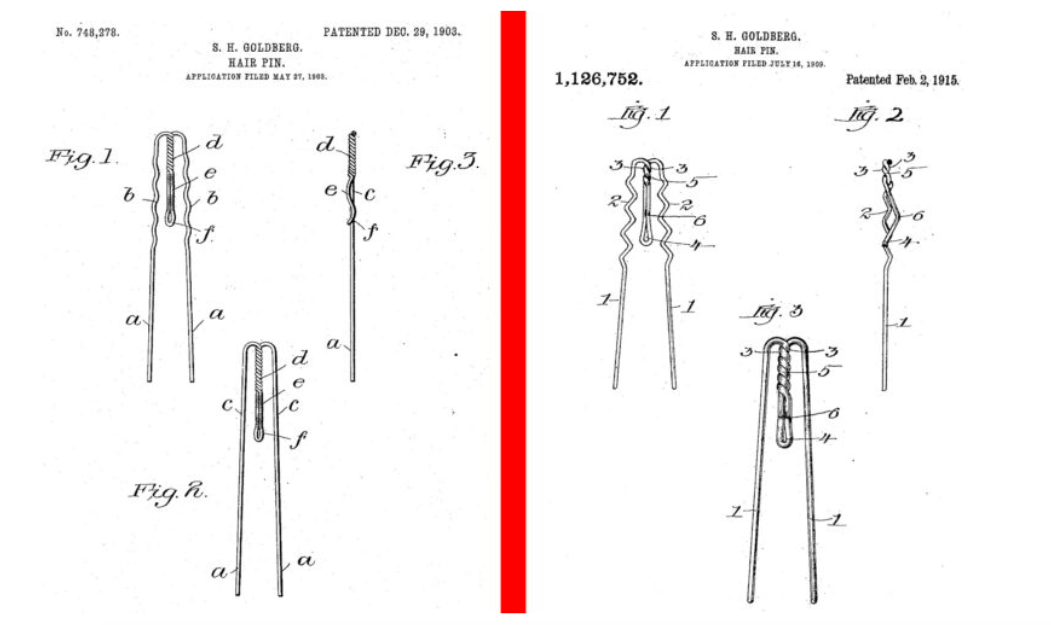

Established in 1903, Sol's empire was called Hump Hair Pin MFG Co., named after the "humped" center leg that helped the company's patented three-prong hair pin stay in place:

Here's a bit of info on that hairpin that catapulted the Goldberg family to the top of Chicago's social ladder, via the Made in Chicago Museum :

In 1903, shortly after procuring a patent for a three-pronged hair pin with a crooked or "humped" center leg (a tiny but significant innovation), Goldberg organized the Hump Hair Pin Company to deliver his creation to the women of the world. The product was, he claimed, "the first hair pin ever devised that does not fall out," as the titular hump could more effectively grip and hold the hair in place, or "Lock the Locks," as the slogan went.

It might not have been the Model T, but in the heyday of the up-do, the Hump Hair Pin—recognized for its familiar "good luck camel" logo—helped make Sol Goldberg a multi-millionaire. From the 1910s through the 1930s, he became a fairly prominent public figure in Chicago high society, twirling his manufacturing success into high-profile real estate ventures and political influence.

The Bobbed Hairdo Leads To The Bobby Pin

Bobbed hairstyles became huge in the 1920s thanks largely to famed ballroom dancer Irene Castle; this threatened Goldberg's empire. Luckily, the successful businessman managed to adapt by selling the Bobby Pin, a hair-holding device for short hairstyles that involves two ends of wire pressed together tightly. You see how the two ends of the hair pin are far apart in the image above? The bobby pin closes that gap:

(I should apologize to women readers, because I'm sure me explaining the difference between hairpins and bobby pins is insulting. I just didn't know! Please forgive my ignorance).

Sol’s Badass Wife Ruth Goldberg Changes Her Name To Gaylord

If you read elsewhere about the Gaylord Gladiator — the car that was supposed to be the main subject of this article before I got side-tracked looking at hairpin patents in what has to be the greatest historical article about hairpins ever — you'll probably see websites claiming that the two brothers who commissioned the car made their money from their dad's Bobby Pin invention. In reality, Goldberg made his fortune on his hairpins and all sorts of other smart investments, and while — sure — he made out well pushing Bobby Pins, he likely didn't invent them. From the aforementioned incredible article:

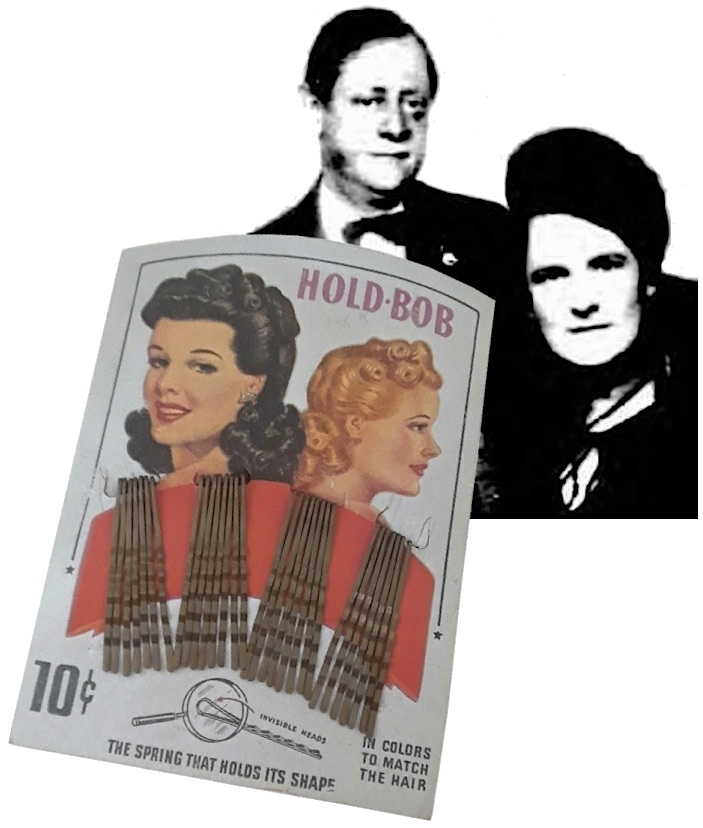

...it's probably safe to say [Goldberg] did not invent the bobby pin. That innovation gets credited to a whole bunch of folks—from Sol's old rival Frank DeLong to Luis Marcus in San Francisco. As for the bobby pin sold by the Hump Hair Pin MFG Co.—marketed as the "Hold-Bob"—not even that concept, it seems, was Sol's.

Many years later, his widow Ruth acknowledged that she'd come up with the idea for the Hold-Bob while out for a leisurely game of golf.

Among Goldberg's other revenue streams was a tire-retreading patent. From the New York Times' story on Goldberg's death:

Early in his career Mr. Goldberg had purchased a patent for retreading automobile tires which he later sold for $2,500,000 and a royalty of $1 on each tire so treated.

Anyway, the Goldberg family was very rich, and yet, the family changed its name.

It turns out that, after Sol died of a heart ailment at age 53 in 1940, his wife Ruth took over and changed not just the company name to Gaylord, but also her own last name. Plus, she convinced her sons do to the same, per the Made in Chicago Museum:

There is no clear indication as to what inspired the name change, but Ruth Goldberg clearly loved the ring of it—so much so that she changed her own surname to match it. Even after re-marrying a year later, to a New York industrialist named Jack Weaver, she carried on as Ruth K. Gaylord, and—stranger still—convinced her four adult children to become Gaylords, as well.

Ruth, by the way, was apparently a huge factor in her husband's success, and also quite confident in her abilities. Look at this badass quote:

"Any woman can outdo her husband in business if she wants to put her mind to it. The trouble is that enough women don't want to put their minds to anything. They'd rather be dumb, because men like them better that way."

Apparently, when U.S. government tried curbing steel use at the homefront during World War II, Ruth successfully petitioned that hairpins were an important factor in keeping up women's morale:

"The people in charge," she said in 1943, "had to be educated to the importance of hairpins. What men can't understand is that hairpins, far from being a triviality, are an essential part of women's apparel." Her efforts worked, as she won some concessions on the number and length of pins her plant could start producing.

The company lasted roughly 30 years after Sol's death; during that time, two of the three sons, Jim and Ed, approached a Friedrichshafen-based vehicle repair company called Fahrzeug-Instandzetzung GmbH Friedrichshafen, or FIF for short, to develop a special vehicle.

As Motor Trend put it, the vehicle was to be "engineered around standard American parts by professionals under the inspired direction of 2 young Gaylord Sons, Jim K. and Edward."

The Gladiator’s Ties To Famous Transmission Company, ZF

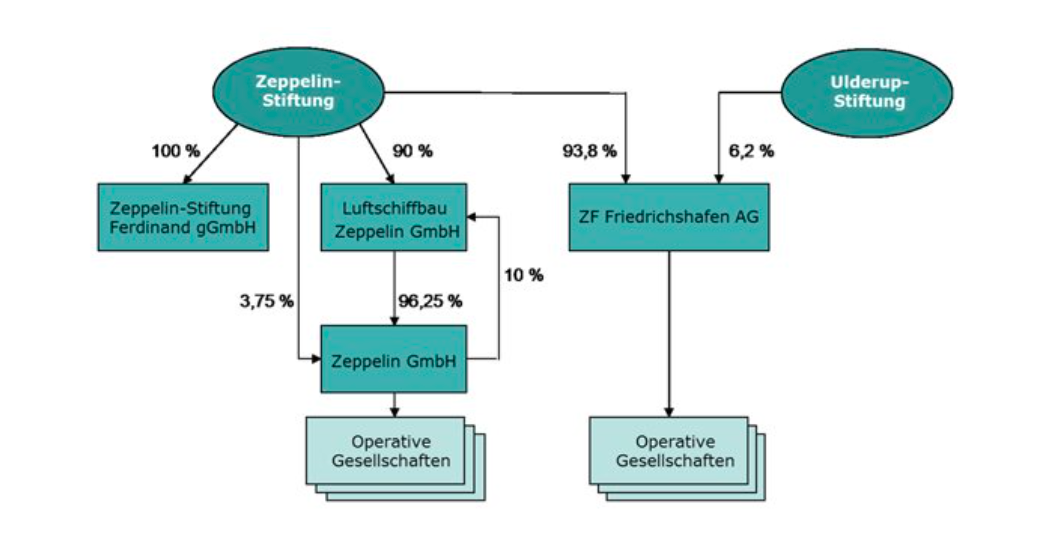

In the early 20th century, Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, the founder of the zeppelin company Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH, needed someone to build quiet, strong transmissions — especially ones that could take outputs from multiple engines and feed them to a single propellor (a complex task that required clutches that would allow motors that died to decouple from the driveline). As a result, the company founded Zahnradfabrik GmbH, also based in Friedrichshafen.

Zahnradfrabrik, which translates to "gear factory," later shortened its name to "ZF," the name that many automobile enthusiasts know as the maker of arguably the greatest automatic transmission of the modern era, the ZF eight-speed.

I mention ZF because FIF, the company that built the Gaylord Gladiator, later became part of the Zeppelin Group (Zeppelin GmbH), which — like ZF — is a part of the "Zeppelin Foundation" (Zeppelin Stiftung).

This is why ZF showed the Gladiator off to journalists last week at the German Car of the Year event, and it's why I got to see this amazing vehicle in the first place.

The Car Started Off Ugly, But Then Became Beautiful (Mostly)

The car is stunning, and that's not just coming from me. One of the world's leading automobile designers — a man who penned some of the most legendary European supercars — was there in the room, and his take was that the car looks great, though there are a few proportions he would change. (I'm not mentioning his name, since he wasn't aware he was on the record).

Anyway, see for yourself:

The designer specifically pointed out how much he liked the flush turn signals, which were extremely uncommon in the 1950s:

Brooks Stevens, the legendary industrial designer behind the Jeep Wagoneer, Studebaker Hawk, and even Oscar Meyer Wienermobile, was apparently thrilled to have been handed the contract by the Gaylord brothers. Motor Trend interviewed Stevens in its December, 1955 issue, writing:

Brooks Stevens well remembers his first instructions, relayed verbally to him by Jim: "The car must have 'clamshell' fender design, different headlight treatment but with function. The theme should be sound rather than futuristic or controversial. The car must be relatively small but still have more passenger room than any other car being built for 2 passengers. It must be completely weather proof, but also fully convertible when wanted. Lastly the grille should be a trademark worthy of perpetuation.

At first reading, the above might seem to be an irrelevant collection of details. Stevens did not react as though it were. He felt that here at last was his dream commission, even tho styling was subordinate to engineering by order. It was the kind of car that everyone talked about but never made.

The car didn't always look this elegant; early prototypes, built by Ravensburg-based German coachbuilder Herman Spohn, actually featured enormous round Lucas P-100 headlights like the ones shown in the ad below; apparently the Gaylord brothers were fans of the lights.

Those lights made way for four smaller lights up front, and the fenders also changed shape, no longer open at the front.

It makes sense that the seasoned designer I was hanging out with in Friedrichshafen mentioned that he'd make some tweaks to proportions, because even in 1955, while the vehicle was being developed, Motor Trend discussed compromises that had to be made on that front:

Length/width ratio was originally to be based on Jaguar's approximate 3 to 1, which Stevens considers to be good. However, engineering dictated American chassis and engine components so the car's litheness (readily apparent even in the photos) had to be achieved thru styling illusions rather than true dimensions. Using stylists' terminology, the sides were "sucked in" and the length "stretched."

Things Didn’t Go Well For Gaylord And Its ‘Ultimate’ Car

A number of sources say the Gaylord brothers had serious issues when it came to actually building the Gladiators, which the brothers hoped to put into series production of about 25 units, per Motor Trend. Apparently Spohn's bodywork wasn't good enough (a website devoted to defunct car companies, makesthatdidntmakeit, says the coachbuilder used lots of lead, which "deteriorated" quickly). Some sources say FIF apparently couldn't satisfy the brothers, either, with Car Throttle writing:

...the Gaylord brothers, already stressed to breaking point by the process of trying to realise their dream car, were not happy with the work done by the German factory. Production was halted and a lawsuit began.

Some re-tellers of the Gladiator story claim that the legal wrangling drove Jim to a nervous breakdown, after which Ed persuaded him to drop the whole idea of building the world's best car. Others tell of a dream thwarted by the economic realities of asking $17,500 ($200,000 today) for a car at that time in history.

The Zeppelin Group's re-telling of the Gaylord Gladiator story makes no mention of a lawsuit. What The Zeppelin Group does say is that the Gaylords chose to build their cars in Germany "because the brothers already knew the quality label of 'made in Germany' back then."

The company goes on:

After failing with the first bodywork the brothers decided to give the task to the so-called "FIF", a vehicle repair facility at Friedrichshafen. Building the car took more than a year, lots of sleepless nights, many transatlantic calls and frequent travels of the brothers between America and Friedrichshafen. But they never gave up, believed in their dream and kept on working on the spectacular car. And in the end the FIF delivered.

I myself haven't found a good source that verifies Gaylord's lawsuit with FIF, though issues with Spohn are well-documented.

In any case, it's fairly well-established that a major contributor to the failure of the Gaylord Gladiator vehicle — more so than any lawsuit — was its exorbitant price, coming in at roughly the same as two Mercedes 300 SLs.

And it's really no surprise. Look at Motor Trend's 1955 issue, and you'll see that the magazine sort of predicted such an outcome. Here's the operative quote from the publication:

Every blue moon, a dedicated person or group attempts to produce for sale in at least some quantity an automobile upon which a price is set after it is styled and engineered. Such a car is the Gaylord. In the past, many efforts like this have met with varying degrees of no success. We might cite England's pre-war Squire, postwar Invicta; France's struggle to keep alive the Talbot Lago and disinter the Bugatti; Spain's government-subsidized Pegaso, and America's own Cunningham Vignale.

To be fair, the magazine also mentions Mercedes and Rolls Royce, two automakers that remained despite their high price tags. But it's clear that Motor Trend approached the Gladiator with healthy skepticism

The Vehicle Was Far Ahead Of Its Time

Even though Gaylord only ever built one production-level car, that doesn't mean the vehicle was lacking. Again, the price of roughly $17,000 at the time was the main issue — you could buy a nice house for that back in 1957. The car itself was beautifully built, and featured elements never before seen on a production car.

The top, for example. That's not a fixed roof, it's a hardtop convertible actuated via a power switch. That was pretty much unheard of in 1957. Other features like power seats, power windows, power steering, air conditioning, and power-assist brakes were features you'd only find in top-of-the line automobiles of the era.

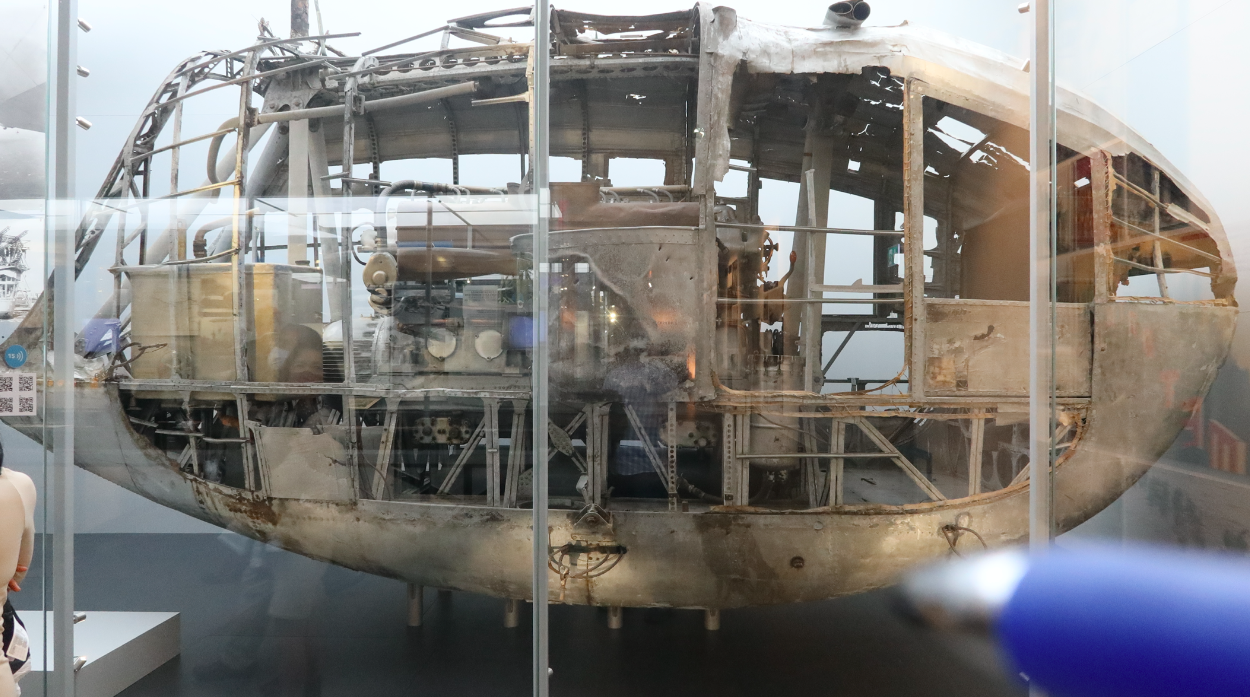

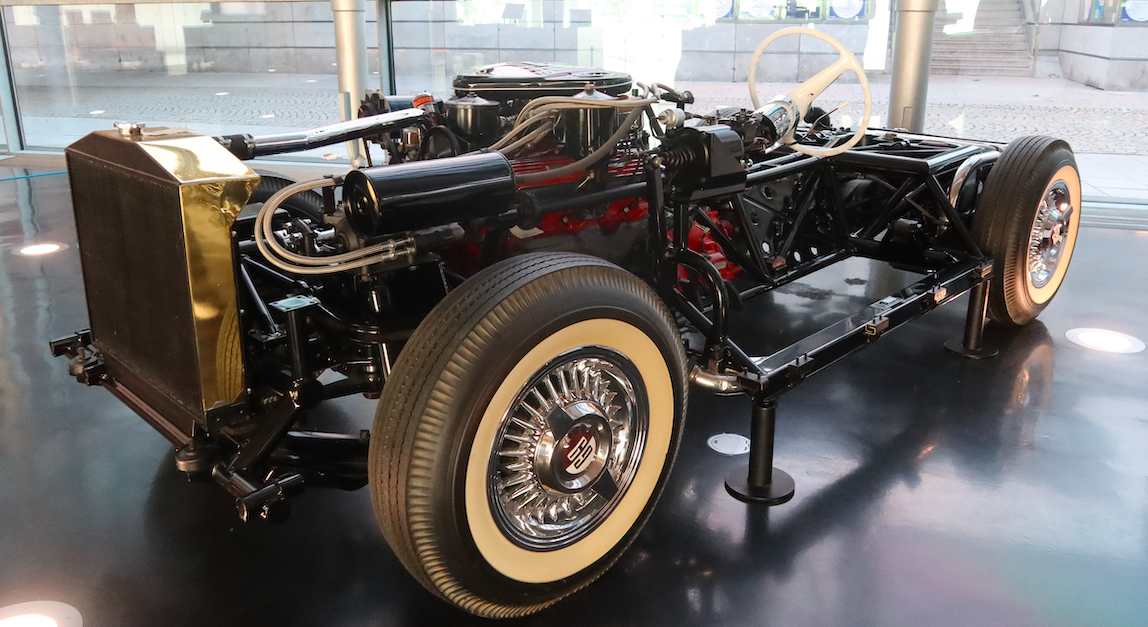

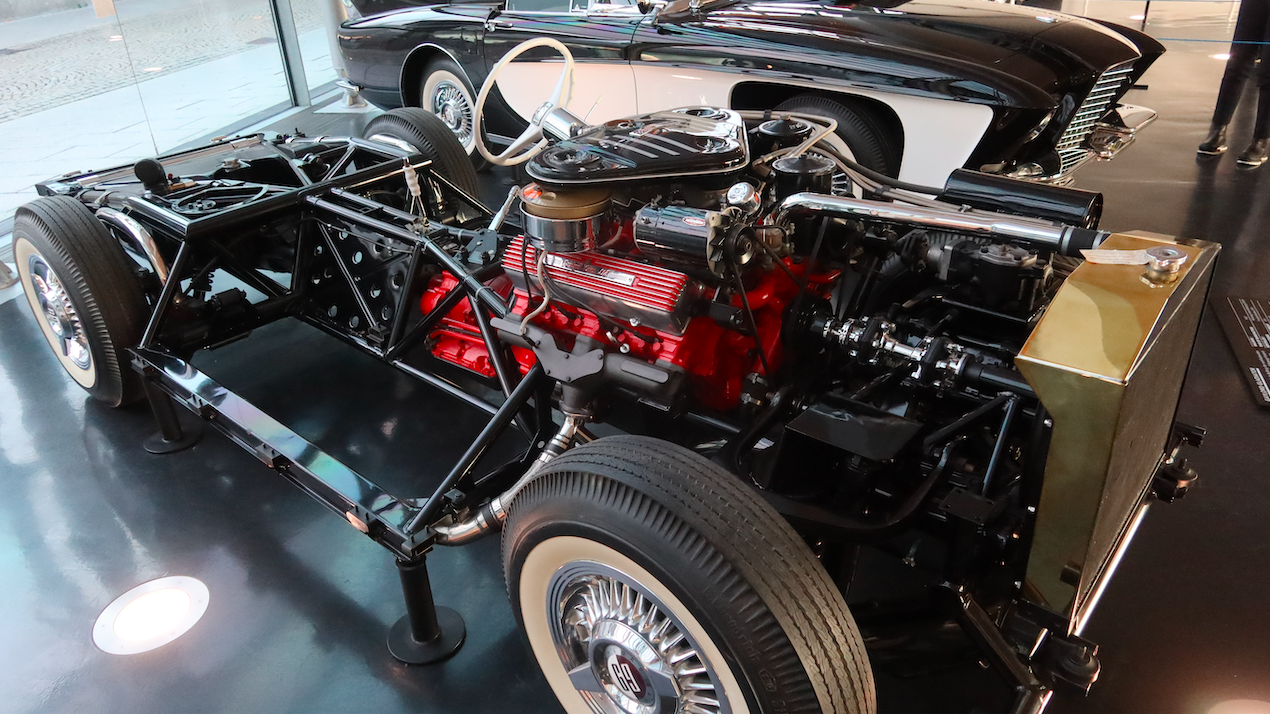

As for the chassis, that too was at the Zeppelin museum in Friedrichshafen. It's a tubular construction with a leaf-sprung solid axle out back and a coil-sprung front independent design.

Per Motor Trend, the vehicle focused heavily on isolating the cabin from noise and vibration. Per the publication:

The dual-wishbone frame is constructed front light but super-strong and -costly chrome-moly steel alloy. Nothing is attached to it that is not insulated in rubber. This passion for isolating metal-to-metal contact is even carried into a revolutionary new drive arrangement where the shaft's two pieces are connected one to the other by a strong telescopic rubber grip that can cushion any V8's torque.

I'm assuming Motor Trend is referring to the driveshaft there, though I will note that the long shaft that spans from the engine's water pump pulley to the engine fan also contains two rubber blocks:

The engine, by the way, is a ~360 cubic inch Cadillac V8 (the prototype car shown at the 1955 Paris Motor Show had a Chrysler V8, per Motor Trend) making around 305 horsepower and sending that power through a four-speed GM-developed Hydramatic automatic transmission. Even a four-speed auto was fairly advanced for the 1950s, when two and three-speeds abounded.

There's so much more to this car that you should check out, including a spare tire holding mechanism that slides fore-aft to allow for easy access, a ridiculously cool trunk lid, and a glorious V8 rumble:

The Gaylord Gladiator at the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen is said to be the only one in existence, not because all others were lost, but because Gaylord only ever completed a single Gladiator.