How To Push-Start A Car And Why You Can't Do It With An Automatic

If you've ever wondered how you can start a car without using the starter motor, allow me to demonstrate the art of the "push-start," also called the "bump-start" or "roll-start." It's a way to use the motion of a car to fire up its engine. Here's a look at how this joyful automotive pastime works, and why you can't push-start a vehicle with an automatic transmission.

I'm in the middle of a possibly-never-ending road-trip in my 1985 Jeep J10. So far, between my initial destination of North Carolina to see my coworker and his amazingly cheap electric car and my stop in Dallas to see an old Chrysler engineering friend, I've driven a total of 2,200 miles. I now find myself at my brother's apartment in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

The parking lot out front of his abode is steep, so over the past few days, I've been doing what I always do when parked on a grade in a vehicle with a stick shift: I roll-start the car. My brother seemed interested in this concept, so I figured I'd do a little video and write-up on it.

What Is A Push-Start?

To start an internal combustion engine, you need four things: Spark, air, fuel, and compression. Especially on older cars, spark and fuel delivery are both tied to the rotation of the engine, but even on new cars with electric fuel pumps and distributorless ignition systems, you can't just start the engine right away without first cranking it over a bit to build compression.

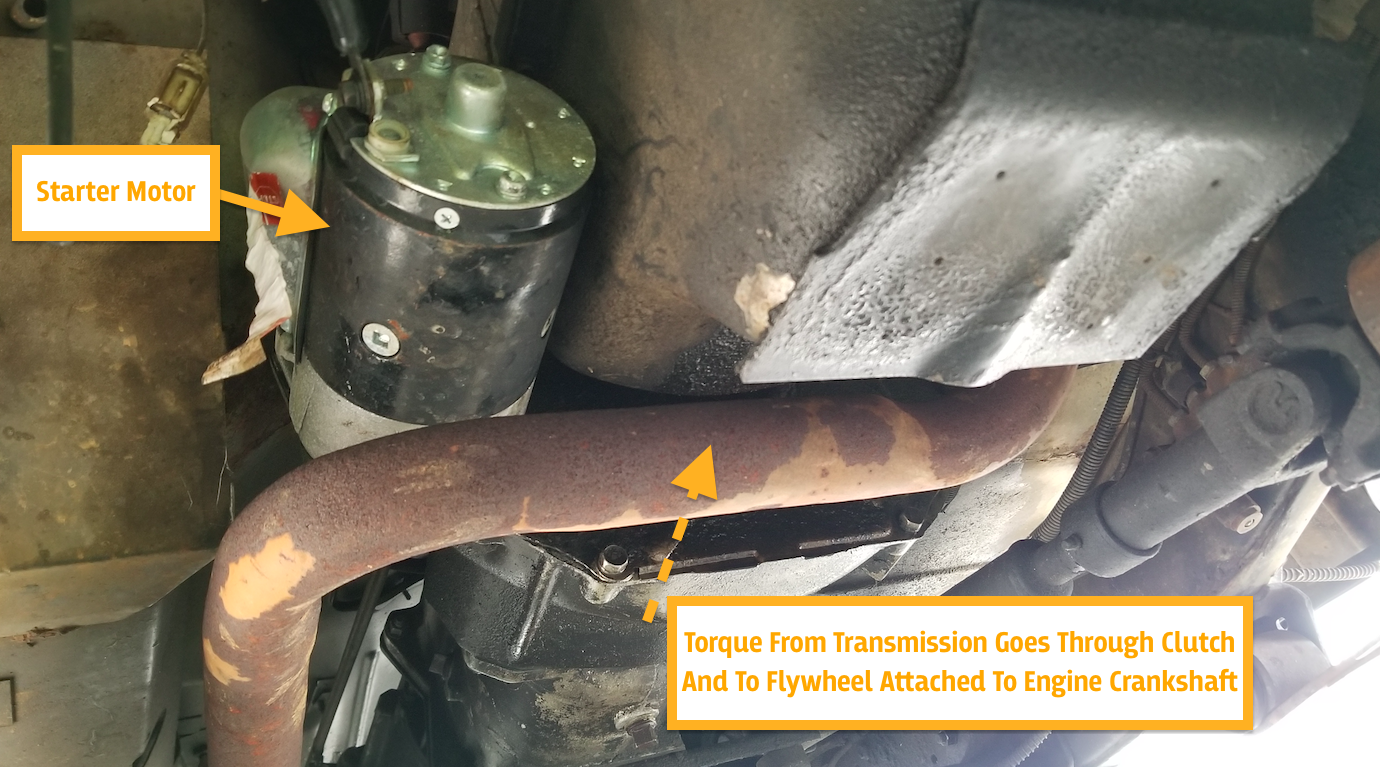

Most vehicles use a starter motor to do this initial cranking. A starter motor, shown above, simply engages the teeth on an engine's flywheel, rotating it and the crankshaft that it's bolted to. The crankshaft is hooked to the connecting rods, which are connected to pistons via wrist pins. Rotating the flywheel spins the crankshaft, which pushes and pulls connecting rods and their pistons, creating compression and allowing for air intake and exhaust into and out of an engine.

But an engine doesn't care whether it's a starter motor or something else turning it over. You could, theoretically, use an old hand crank if you could find a way to safely hook it to your crankshaft pulley. Or, if your car is equipped with a manual transmission, you could simply use the rotation of your wheels to crank the engine over to get the motor started. Because it's fun.

How Do You Do It?

Here are the main steps needed to bump-start a car:

-

Step on the brake pedal with your right foot. If your car is old and normally requires a pump of the gas to fire quickly, kick that accelerator pedal once or twice. I also like to turn off the air conditioning so the engine is easier to spin over.

-

Turn the key to the "on" position. This will turn on your ignition.

-

With your right foot on the brake, step on the clutch with your left foot, and shift the vehicle into gear. Note that, if you're parked on a hill, when you press the clutch, the vehicle may want to move if your park brake isn't particularly strong. Be prepared to hold down the brake pedal firmly, as you don't have power assist when the engine is off. Another note: If you're going backwards, you shift into reverse, of course. If you're going to roll forward, choose the gear based on how quickly you think you'll be able to get moving. If it's going to be a slow roll, first gear may be the play. If you'll get going a bit quicker, try second.

-

Release your park brake.

-

Now, with your left foot on the clutch and your right foot on the brake, lift your right foot and allow yourself to roll down the grade (or be pushed on a a flat road, if you have friends giving your vehicle a shove).

-

Once the vehicle is moving, quickly lift off the clutch. The torque from your wheel swill quickly be sent from your wheels and through your driveline, spinning your engine over. Your engine should start.

-

Quickly get back on the clutch and brake (but if your buddies are running closely behind you after giving you a push, be careful not to slam the brakes too hard, or you might end up with friends stuck to your back window).

That's pretty much the whole operation. Fairly straightforward and loads of fun.

How Does A Push-Start Work?

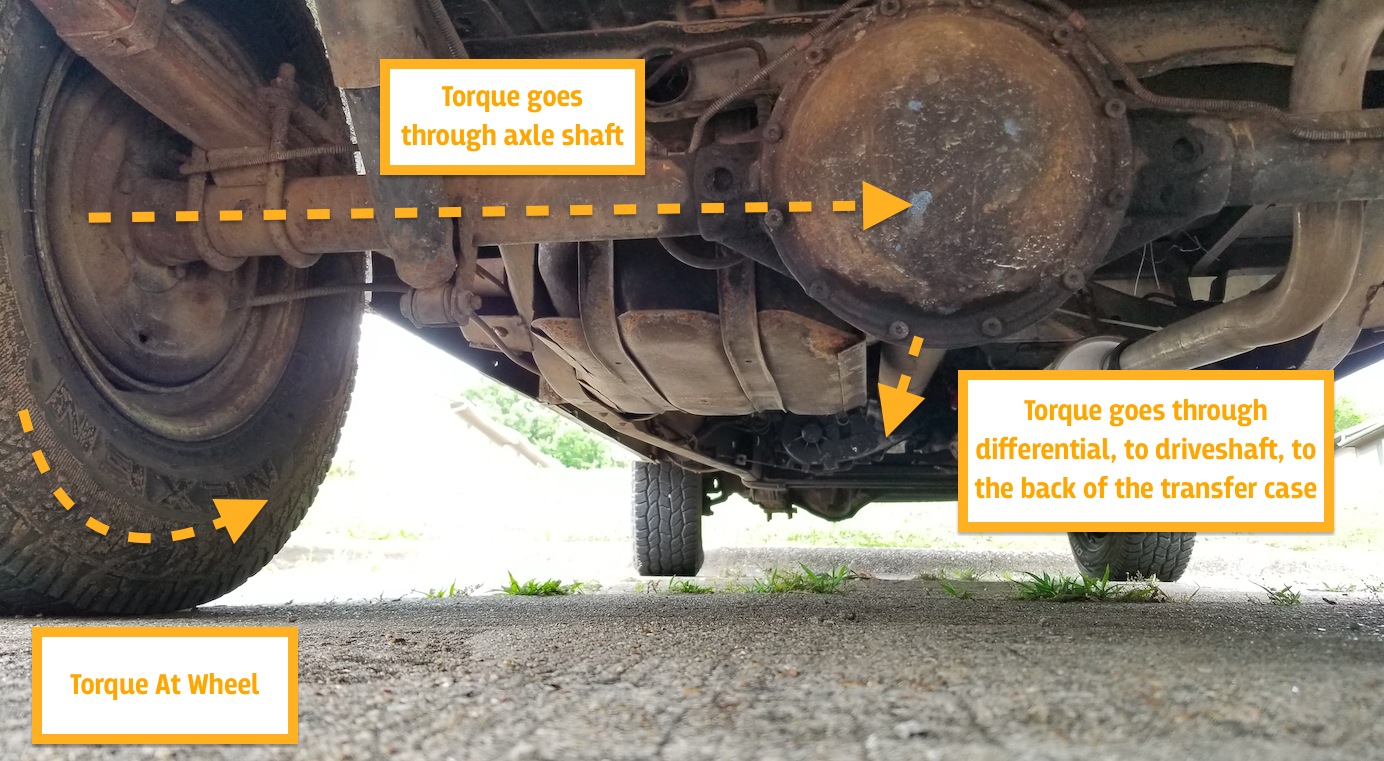

Instead of relying on a starter motor to spin your flywheel, push-starting a car uses the torque generated by the friction between your tire and the ground to rotate your axle shafts, which send torque through your differential(s), which send torque into your transmission, which is hooked to your engine's flywheel via a clutch disc and pressure plate. Let's follow the path of torque delvery on my Jeep J10, starting from the wheels:

Spinning the wheels rotates the axle shafts in the rear axle tube (my vehicle is in rear-wheel drive mode), which rotates the differential ring gear, which rotates the rear driveshaft through the pinion.

The driveshaft spins the transfer case output yoke. That transfer case is bolted to the transmission, and rotates the transmission's output shaft.

The transmission, when in gear, sends torque to its input shaft and through a clutch disc to the engine's flywheel, turning the motor over.

Let's talk about the clutch, since it's the key player in this joyful activity known as the roll-start.

As Paul from YouTube channel Gearbox Video explains in his video above, the flywheel is a big steel disc that bolts to the engine's crankshaft. Normally, the teeth on a starter motor spin the ring gear that's pressed onto the outside of this flywheel to turn the engine over.

In the case of a roll-start, torque goes from the wheels through the various aforementioned components and through the clutch disc. The clutch disc is splined onto the input shaft of the manual transmission. This input shaft spins because, when you're in gear, the input and output shaft of the trans are connected, and we've already established that the trans output shaft is being powered by the torque that originated at the wheels and went through the transfer case.

When your foot is on the clutch, you're preventing the clutch from being clamped between a pressure plate and the flywheel. When your vehicle is rolling, and you let off the clutch pedal to bump-start the car, the pressure plate squeezes the clutch disc (which spins at the same rate as the transmission input shaft, since they're splined together) against the flywheel (which spins at the same rate as the engine, since it's bolted to the crankshaft), forcing the two components to spin together. With the trans and engine essentially "locked" together, torque is transferred to the motor, rotating it, allowing it to make compression, pump fuel, send spark to the cylinders, take in air, and ultimately fire up.

Why Can’t You Push-Start A Car With An Automatic?

I reached out to some automotive engineers to solidify my understanding of why a push-start won't work on a vehicle with an automatic transmission. What I came away with is the fact that automatics' reliance on fluid pressure to engage gears—and their use of a fluid coupling instead of a clutch—makes a push-start darn-near impossible.

Here's what transmission development engineer Adam Cole, who works for a major automaker, told me:

[A bump-start] can be accomplished in a manual gearbox through the use of the traditional clutch. When the clutch is engaged (along with a gear), the friction disc holds the engine and trans together, thus creating one continuous chain from the engine all the way to the driven tires. Therefore, you are able to utilize the torque produced by the rotation of the wheels to sort of act like a big starter for the engine.

However, in the transmission that I am familiar with, this is not possible. The main difference, as I know you are aware, is the replacement of a traditional clutch/pressure plate setup with a torque converter. A torque converter is a fluid coupling that transfers rotational acceleration from a prime mover (the engine) into a rotating driven load (the transmission). By the engine and transmission not being physically connected, this allows the engine to continue rotating while the wheels stay stationary. Pretty much everything in an automatic transmission is driven by oil pressure. All gears within an automatic transmission are engaged through the use of oil pressure. It is used to compress friction elements within clutches which ultimately results in a changing gear ratio and it also can "fire" dog clutches in order to achieve the same outcome.

He continues:

So in order for a gear to become engaged, line pressure must first be built up but you cannot increase line pressure by spinning the output shaft of the transmission. You would also have to produce enough torque in order to spin the torque converter fast enough to restart the engine. However, no clutches would be engaged, therefore the torque generated by the spinning wheels will never make it to the torque converter which ultimately results in the inability to bump-start the vehicle.

Another engineer with a major auto supplier echoed these thoughts, telling me:

Hydraulic pressure is the problem.

When you say bump-start, I assume you're talking about getting the wheels going with the car off, then popping the clutch to get the engine spinning. The main reason you can do that in a manual is that the manual clutch creates a physical connection from the engine to the wheels.

In an automatic, there are a few limiting factors. First, hydraulic pressure is required to create any physical connection from the transmission input to the output. Some transmissions may use electronic pumps to generate that pressure, but it wont work for most of them if you put it in "drive" with the engine off. Most automatics wont even let you put it into drive with the car off. You'd need that hydraulic pressure to lock the TC, and the clutches to make first gear work. I don't know of any TCs that use electronic pumps to generate pressure.

The first video in this section, uploaded to YouTube by speedkar99, shows the clutches that engage the gears, and the valve bodies that actuate the clutches using oil pressure or "line pressure." The video also shows the transmission oil pump which is driven by the engine. If the engine isn't spinning, the pump isn't working, and there's no line pressure to actuate gears or lock up the torque converter. So if you push your car when it's in drive, chances are, you won't even be turning the transmission input shaft.

A torque converter, by the way, is essentially what you see in the "fluid coupling" YouTube video above. Aside from when the torque converter is locked up, there is no direct, physical connection between the input (the impeller, which is tied to the engine rotation since it's part of the torque converter housing bolted to the flex plate, which is essentially the automatic equivalent of a flywheel) and the output (the turbine, which spins the transmission input shaft). As such, spinning the output (the transmission) would essentially attempt to work the fluid coupling backward, which wouldn't work so well.

A few things to note: In some cases, especially on hybrids, there might be electric pumps that could allow for line pressure in the transmission to engage gears and lock the torque converter. Plus, I have on multiple occasions turned my automatic 1992 Jeep Cherokee off on the highway, then turned the key to the "on" position, and noticed that the engine fired right up. This was likely due to there being residual line pressure during the short engine-off time. The torque converter was possibly locked, or the turbine was able to spin up the impeller due to the high rotational speeds.

So there are some scenarios where an auto transmission "bump-start" could be possible, theoretically. But basically, if you want to do it by simply rolling your car down a hill or having a buddy push you, you'll need a manual.

And if you have one of those, and you've got a sloped parking spot or some buddies to push you, you absolutely should give it a try. Because push-starts are fun, though I can't really explain why.