How I Rebuilt My Jeep Truck's Transmission In My Kitchen For Under $150

The 2020 Jeep Gladiator has been getting lots of attention lately, but unfortunately, my own Jeep pickup—a 1985 Jeep J10—has not. The descendant of the original Gladiator in my driveway has had a broken four-speed manual transmission for years now, but I recently got around to fixing it on my kitchen counter, and it was dirt cheap. Here's how I did it.

After completing a nearly 4,000-mile road trip in a $500 Postal Jeep that should have gone to a junkyard decades ago, I am ready to take a short break from resuscitating crap-cans. Instead, I'm turning my attention to beautiful vehicles in my own driveway that need love, and chief among them is my 1985 Jeep J10. It's a pickup that I bought over four years ago, and promised to restore. Instead, it's languished in my backyard and driveway ever since, with a bad input shaft bearing that made a terrible noise anytime my left foot was off the clutch. That all ends now.

Mostly, because I promised the folks organizing the Toledo Jeep Fest that my J10 will be part of their indoor exhibit, and that means I have a single week from now to get the vehicle ready. The bad news is that the engine runs like crap, but the good news is that I rebuild the transmission. And it was the most fun I've ever had fixing a car.

Disassembling My Jeep J10's Manual Transmission

I've already described what it was like removing the transmission from my truck. Thanks to a transmission jack, it wasn't as bad as it could have been, but it was still damn difficult. I had to remove the driveshafts connected to the transfer case, move some exhaust parts, disconnect the park brake cables, disconnect the transmission mount, drop the transmission crossmember, and fiddle with many, many more bits before I could get the trans removed from the Jeep's belly.

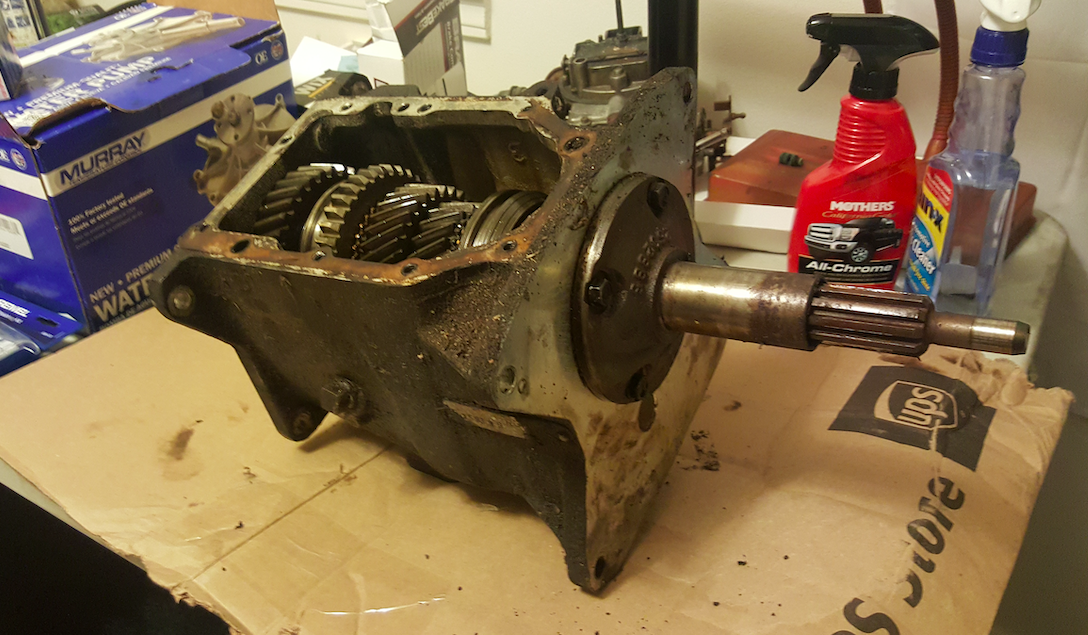

None of that was too bad, even though I'd never dropped this transmission before. But what was tough was the fact that, despite their housings being aluminum, the transmission and the transfer case bolted to the back of it were absurdly heavy and required all of my might to get them out from under the truck and to carry them into my garage.

With the four-speed Tremec T177 "toploader" transmission (called that, since the main access to the gears in the case is from the top) removed, the next task was gutting it. That required removing the front bearing retainer and taking off the snap rings on the bearings. That wasn't too hard, but what was a hell of a job was pressing the bearings off the input shaft and main shaft. Luckily, my friends Derek and Chris invited me to their friend Adam's garage.

As the three had recently done some work on a Honda transmission, they were ready to get this comparatively basic trans torn down, and they even had a bearing puller.

Unfortunately, the bearing puller kept slipping off the bearing separator tool, but eventually, we came up with some solutions and got everything torn down. Here's our makeshift jig for output shaft bearing removal:

I pounded the end of that output shaft with a heavy rubber mallet, and eureka! The whole transmission case dropped, leaving only the bearing puller and the bearing itself:

This is not the manufacturer-recommended method for transmission disassembly, but it worked well for me.

Rebuilding My Jeep J10's Manual Transmission

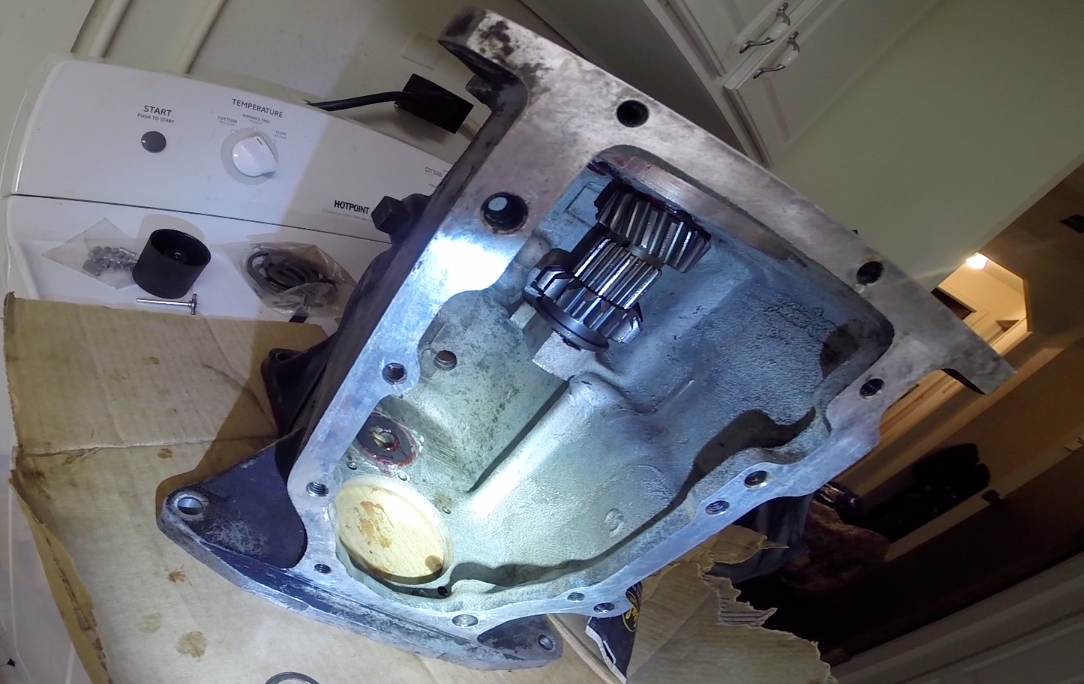

With some finesse with some snap ring pliers, we got all the gears out of the case, and then I drove home so I could wrench where most normal people fix their manual transmissions: in the kitchen.

I soaked both the case and gears overnight in a bucket of hot water and degreaser, and everything seemed in really nice order by the time I was finished. Well, at least in terms of cleanliness. As for the actual condition of the parts, things looked fine except for the reverse gear, which had some chunks missing:

Those chunks had apparently been ground into fine powder, and then been attracted to the magnet at the bottom fo the case:

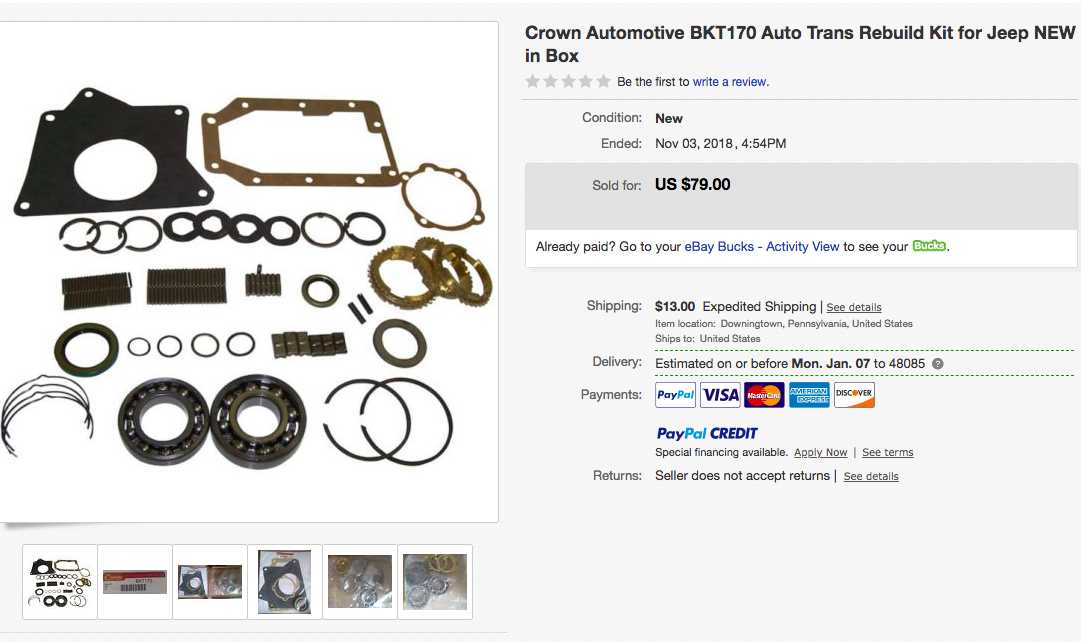

Of course, I went out and bought a new reverse slider gear, which was only $38. I did not replace the synchro sleeve/reverse gear to which it mates, as it seemed in excellent shape. And also, because, as I've made clear numerous times on this website, I'm a cheap, cheap bastard. That's why, when it came time to buy a rebuild kit, I acquired the least expensive one I could find, which at the time cost only $83 shipped (see below).

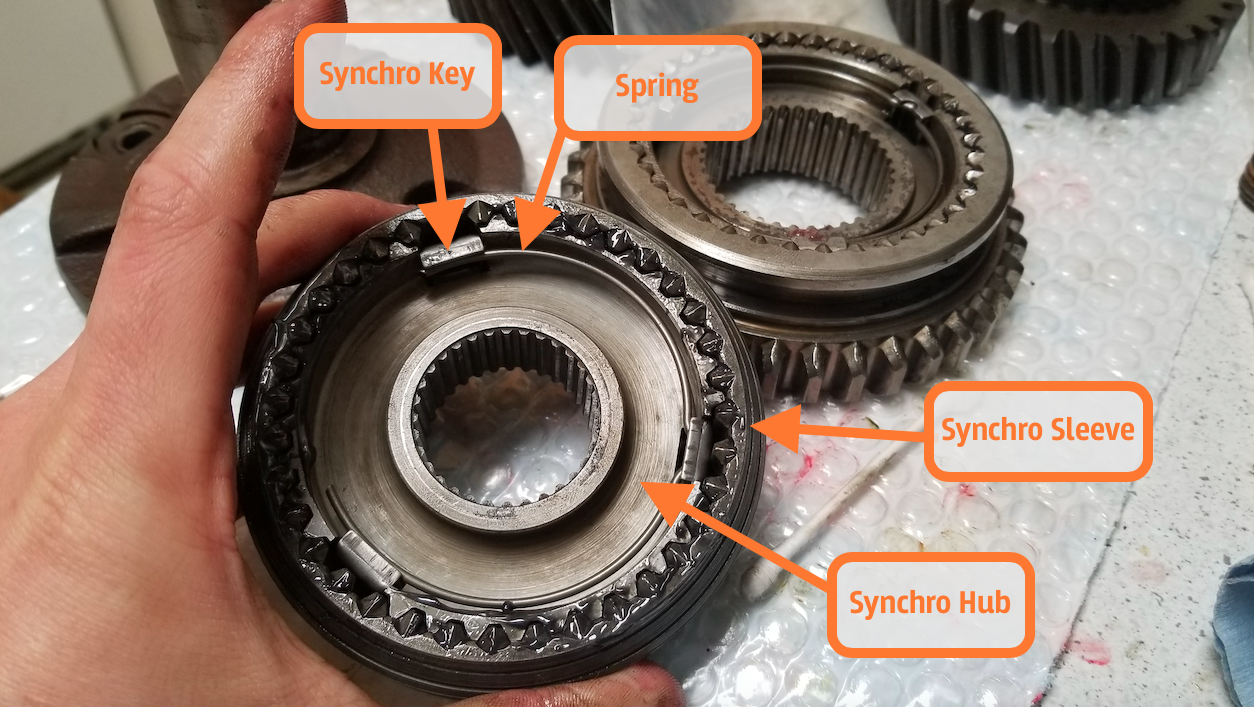

It came with new gaskets, springs, synchro keys, brass synchro blocking rings, shaft seals, and thrust washers.

The first thing I did once I'd cleaned everything up was open my laptop to a YouTube video by transmission expert GearBoxVideo, who does an excellent job explaining step-by-step how to rebuild this manual transmission. Then I loaded up both ends of my reverse idler gear with some needle bearings using sticky Red "N" Tacky grease (some say this is a bit too thick for this application, but my friend Brandon and I have had good luck with it in such applications) to help them adhere to the inside of the gear. I then installed the new reverse slider gear onto the splines of the reverse idler. Here's what that looked like:

Then I put the reverse idler and slider into the transmission case with a thrust bearing on each side, nestled between the idler and the aluminum transmission housing. Next, I pounded a steel idler gear shaft in through the side of the case, through the center of the reverse idler shaft, and into part of the cast aluminum housing situated near the bottom of the case. This shaft is what the needle bearings in the reverse idler shaft roll on.

Installing the cluster gear was essentially the same process. I just loaded it up with needle bearings on each side, then slid it into the case with a washer on each side. I accidentally missed that there was a washer inside the cluster gear underneath the needle bearings, so I wasted about an hour trying to figure out why my thrust washers weren't going in. But eventually I figured that out, and it was time to assemble the main shaft.

Assembling the main shaft is a lot of fun, but so was installing needle bearings into the cluster and reverse idler—honestly, the whole process of rebuilding a simple four-speed toploader is just fun.

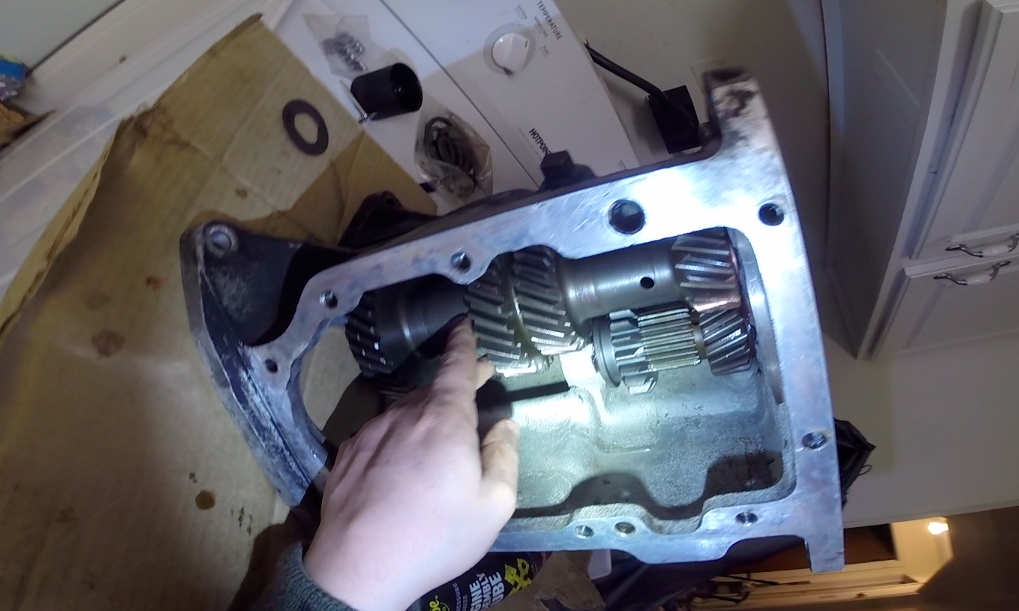

I put together some synchronizer assemblies, which consist of a hub, a sleeve, a spring, and little keys. These are what your shift forks—which connect to your shifter lever in your car—move fore and aft to engage gears. Along with the brass synchro rings, shown below, and the synchronizer cone and synchro teeth found on the gear itself, these synchro assemblies allow you to smoothly change gears without having to rev-match.

In my hand below, just above and to the left of my thumb, you'll see a smooth surface on this gear. This is the synchro cone, onto which the brass synchro rings grip during gear engagement. And below that smooth surface are the teeth that the synchro sleeve grabs to engage the gear.

To assemble the main shaft shown above, I simply stood it up on its end, and began dropping on gears, synchronizer assemblies, synchronizer blocker rings, and snap rings—lots and lots of extremely stiff, difficult-to-manage snap rings.

In time, I got the top section assembled, and just look at this majestic tower of steel and brass:

Then I flipped it over, installed another gear, synchronizer ring, and snap ring, and alas, the main shaft was complete:

You'll notice that I have it in the freezer. That's because the bearing between this shaft and the transmission case—and also between the input shaft and the case—are press-fit bearings, and I was hoping this shaft would contract.

That input shaft, by the way, goes onto the left side of the main shaft shown above. There are some needle bearings between the inside of the input shaft and the part of the main shaft shown on the very left in the image above. Here are those needle bearings:

After sliding the main shaft and input shaft into the transmission case, I heated up the bearings and began pounding them into place using a PVC pipe with the same diameter as the inner race and a sledgehammer.

Prior to pounding on the input shaft bearing, I had to modify it using an angle grinder.

This is, obviously, not optimal, as bearings are precision items, and angle grinders are very much not. But I had no choice, since the snap ring groove wasn't deep enough, causing the snap ring itself to protrude too far out from the bearing outer race.

What this meant was that the bearing retainer, shown below on the left, would not sit flush with the case:

My solution was to hold the inside of the bearing, and angle-grind the outside of the outer race, which spun the bearing, theoretically yielding a relatively even cut. In time, it was deep enough, and the bearing retainer cleared the snap ring.

The final step was to pound in the cluster gear countershaft (this had to be done late in order to fit the main shaft), and then the trans was ready for install.

Before doing that, I had my flywheel shaved by a local machine shop. It had apparently never been shaved since new. I also installed a new clutch kit, which comes with a new pilot bushing, whose installation required me to remove the old one using a brilliant trick involving wheat bread:

The $88 clutch kit came with a clutch, pressure plate, pilot bushing, alignment tool, and throwout bearing, the latter of which wasn't quite what I'd taken out of the Jeep, though Autozone was kind enough to give me the right part for free.

Here's a look at that throwout bearing, which slides along the transmission input shaft bearing retainer as the clutch fork—which is activated by a cable attached to the clutch pedal—moves fore-aft. The bearing then pushes the fingers on the pressure plate and disengages the clutch from the flywheel.

The install was fairly straightforward, as was a clutch adjustment. Now it's all together, and things look good. I even have a new bench cover, which I snagged for $15 at the junkyard:

The transmission rebuild only cost me about $121 between the new reverse slider and the rebuild kit itself, but add the $88 clutch kit, the 80ish bucks I had to spend to fix my shifter lever (whose threads I sheared a while back), and another $20-ish I spent on a new shifter kit/rubber boot, and we're looking at about $300 all-in.

And that's not terrible, especially considering that I've taken this thing on a test drive, and it shifts like a dream.