How Dead Bodies Save Lives Every Day On The Road

This is a Jalopnik Classic post we are re-running in honor of Jalopnik's 20th Anniversary

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Glass explodes. Metal screams against metal. A car crash is a waking nightmare, but one that has become increasingly survivable—and we have piles of dead bodies to thank.

(Warning: This post includes images of dead bodies, used as cadavers and wrapped for anonymity and dignity.)

At the Wayne State University campus in midtown Detroit, there stands an empty building once used by the school's Biomechanical Engineering department. It was here that one of the grandfathers of modern automotive safety, Dr. Lawrence Patrick, first tossed a human corpse down an unused elevator shaft. You know, for science.

While using human remains as test subjects may seem ghoulish, these researchers and donated bodies were, and still are, on the front lines of saving lives.

This is gonna be a creepy one. Buckle up.

“Safety Doesn’t Sell”

If you really want a good scare, check out the crash rates during the U.S. automotive industry's golden era. In the 1950s and '60s cars were not very safe, to put it mildly. Check out this crash test between a modern-day Chevrolet and Jalopnik Deputy Editor Mike Ballaban's favorite classic car, a '59 Chevy Bel Air:

It's not a pleasant sight. The Malibu crumples when it strikes the older Bel Air, keeping the passenger compartment mostly intact and the dummy fairly safe and cozy. The front of the Bel Air, however, throws the crash dummy around the cabin as its front end is crushed into the seats.

It's true that technology and manufacturing techniques weren't as sophisticated back then, but the fact is safety wasn't a priority for automakers for a long time. Automakers knew their cars were killing people. In the post-war years, the auto industry even had a motto that sounds crazy to us today: "Safety doesn't sell." And as Automotive News noted in a 1996 story, there were no federal safety regulations, nor were consumers demanding safer cars en masse.

It was 1946 when car crash deaths in the U.S. first crested 30,000 per year, and that number, while ebbing and rising a bit year by year, never significantly dropped back down.

Ford had tried to sell a "Lifeguard Design" package filled with innovative safety features in 1956. Citing work done by Cornell, Lifeguard Design featured such safety innovations as a padded instrument panel, shatter-proof rearview mirror and a deep-dish steering wheel that would deform instead of impaling the driver. These features may seem like common sense today, but they didn't exactly catch on at the time.

By 1963, traffic fatalities breached 40,000 a year. Just two years later, Ralph Nader published Unsafe At Any Speed, which took aim at the Chevrolet Corvair and safety standards in the auto industry in general. Only two years after that, in 1968, U.S. traffic deaths climbed above 50,000 a year.

So why wasn't anything done sooner? In Ford's case, the safety package quickly fizzled out. Buyers ended up going for those sexy and unsafe Chevys like the Bel Air pictured above to the tune of 190,000 cars more than Ford sold. Henry Ford II even begrudgingly said this about his own general manager, Robert McNamara: "McNamara is selling safety, but Chevrolet is selling cars."

In fact, by 1964, steering columns alone had killed 1.2 million drivers. Much like today's push for cleaner and more efficient cars, automakers knew there was a problem, but wouldn't address the problem until Congress forced their hands in the late '60s.

Even seatbelts were relatively new during this time period. Ford installed them as options on some cars starting in 1955, but other automakers were slow to follow suit until a federal law requiring all cars come with seatbelts in 1968. (The Swedes did it better, installing seat belts standard on Saabs and Volvos by the late 1950s.)

But if automakers weren't interested in saving lives, some academics were. And they went about developing safety enhancements in unusual ways.

The Crash Test Dummies Are People!

Dr. Lawrence Patrick was a professor at Wayne State and, in some ways, he was also one of the first crash test dummies. While gathering data on what the human body could endure, Patrick subjected himself to multiple impact tests, including a 22-pound metal pendulum to the chest and over 400 rides on a rapid-deceleration sled. Patrick's grad students also endured punishment after punishment in the name of safety. In a 1965 paper, Patrick described how his students volunteered for knee impacts of up to 1,000 pounds of force.

But to get the really good data, they had to push past the limits of human endurance. And since it was illegal to kill a grad student—yes, even back then—that meant getting access to some dead bodies.

"God help you if you lived in the vicinity of Wayne State University in the mid-'60s and you donated your body to science," Mary Roach wrote in her book Stiff: The Interesting Lives Of Human Cadavers. Patrick and his students first measured the impact limits of a human skull by tossing a cadaver down an empty elevator shaft in the now-shuttered Shapero Hall in midtown Detroit.

Bodies were slammed, smashed and thrown from deceleration sleds by grateful grad students who were no longer subjected to the same tests themselves. At testing's height in 1966, cadavers were used once a month. The data they gathered was used to write the "Wayne State Tolerance Curve," still used to this day to calculate the amount of force required to cause head injuries in a car crash.

The data was also used to build some of the first reusable crash test dummies, not because using bodies was distasteful, but because a good cadaver for scientific purposes is a difficult thing to get a hold of.

Thanks to advancements in medicine, most bodies donated to science are older and therefore more delicate than younger bodies. However, younger bodies are also more likely to die in such a way as to make them unusable for researchers. According to the Centers for Disease Control, injuries are the leading cause of death to people under 44, and one-fifth of those fatal injuries are caused by car accidents. A body that has already been in a car crash is generally useless for crash testing purposes, which also means that bodies used in testing aren't reusable. Researchers are also are not allowed to test the bodies of children, who are most at risk in car accidents. Cadavers also need special preparation to make their rigid muscles act more like living tissue.

But research using cadavers is in the past, right? In theory, we have the data—we only need to build the dummies to specifications that reflect that data. Well, if you think that we've perfected the crash test dummy after all of this cadaver research, think again.

These days, only a couple of cadavers a year are used in testing at Wayne State, but they are still needed to perfect the next generation of crash test dummy. A lot more industry-wide effort is now put into preventing crashes in the first place—think automatic braking and lane change warning lights—rather than keeping car occupants safe. But the need for human bodies still occasionally arises.

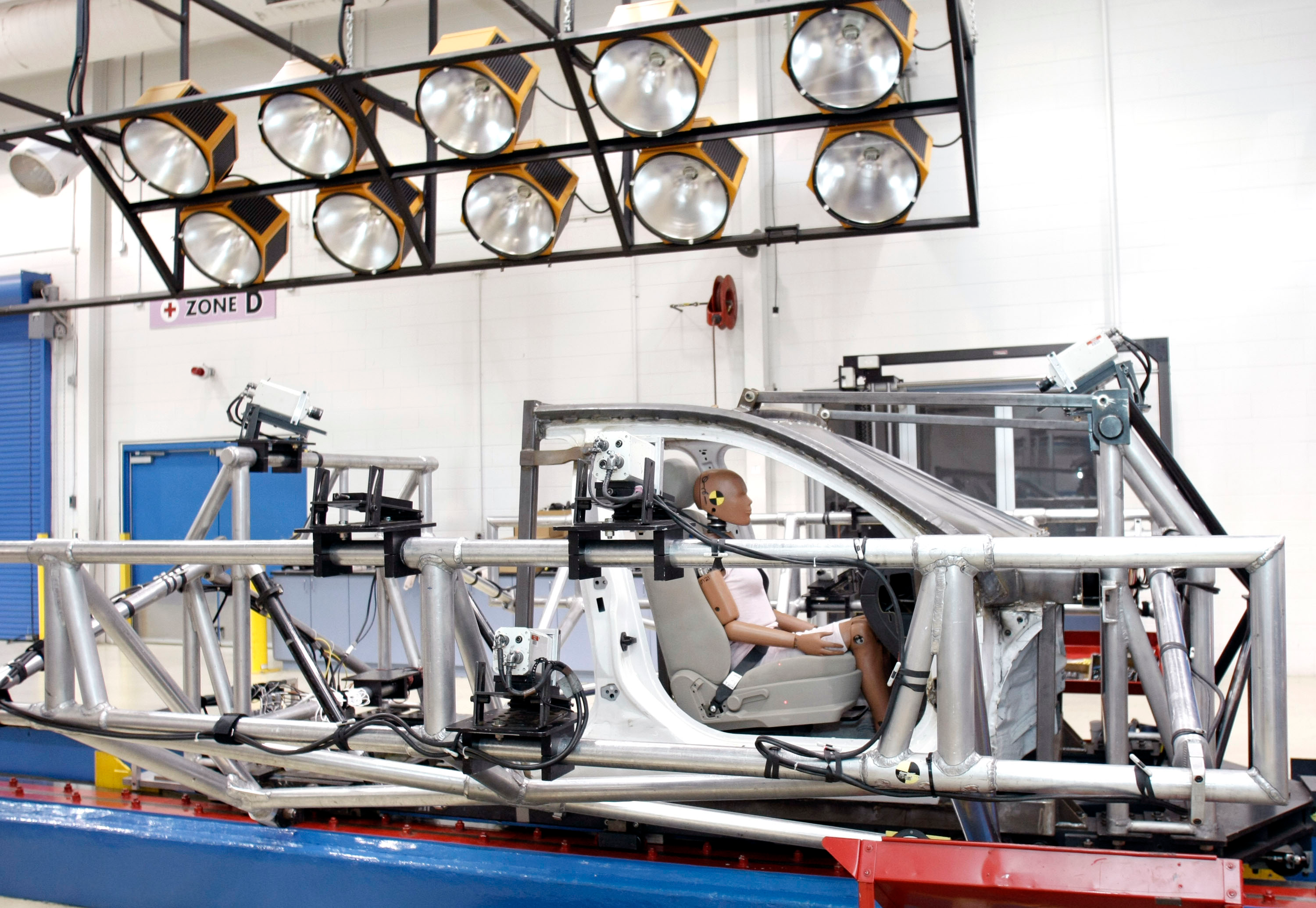

The population is always changing too. For instance, Americans are much heavier on average today than they were in the '60s. Sensors have also become more sensitive and dynamic. New dummies are constantly needed with the latest population data and are now fitted with state-of-the art sensors to provide the clearest information possible.

Bodies are also still used to review other forms of trauma by biomechanical researchers, such as how they respond to improvised explosive devices. Understandably, the armed forces have always had a keen interest in this type of research. The very first crash test dummy was designed to test ejection seats in fighter jets for the Air Force for instance, and the U.S. Army still contracts research through Wayne State to this day.

While human bodies are used in crash testing, the utmost respect is paid to the test subject. Researchers aren't just slamming corpses into walls all day for fun. Universities that receive funding from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, including Wayne State, are instructed to inform the family if their willed body consent forms were not clear enough and all consent forms are reviewed by the NHTSA before cadaver use. The cadavers are also completely wrapped to maintain anonymity and dignity and all researchers sign a pledge to respect the cadavers.

These are, after all, former living humans who put science above vanity and handed their bodies over after death. In a 1995 paper published in the Journal of Trauma, Wayne State biomechanics professor Dr. Albert King calculated that cadaver research has saved over 8,000 lives a year since 1987.

So yes, dead people have saved thousands of lives and continue to help do so today. Kinda makes you wonder what you're doing with your life in the meantime, doesn't it?