How An Alleged Cryptocurrency Scam Put A Texas Car Show In Peril

For years, the Texas Relays Car Show and Donk Contest in Austin brought a passionate but sometimes misunderstood car culture into the spotlight around one of Texas' biggest track and field events. But this year, the show's fate is uncertain after its organizer apparently invested funds in what turned out to be a scam cryptocurrency platform—and then went missing.

"This all came as a shock to everyone," an employee with the Donk Contest at the time the investments were made, who asked not to be named, told Jalopnik.

As cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and others rise and fall and dominate headlines, this group of car enthusiasts is working to ensure a fraudulent one doesn't cost them their event entirely.

"Right now we are just focusing on making sure the show happens, and we believe we will eventually be paid back in full," the employee said.

The Texas Relays Car Show and Donk Contest started with no true organizers or elaborate marketing methods, and it didn't need them. According to the show's website, people simply knew to show up to Austin's Highland Mall during the weekend of Texas Relays—a track and field event for high-school and college athletes held at the University of Texas, and one of the biggest social events in the state for a predominantly young and black crowd.

Typically, a few hundred people and dozens of cars attend the contest around the end of March or beginning of April, while Texas Relays is going on. Houston hip-hop artists come out, and, as the employee of the Donk Contest described it, people bring cars with $15,000 rims and $10,000 paint jobs.

A customized Donk, defined as both generally a large, typically American-made car with big wheels, or, more specifically, a 1971 through 1976 Chevrolet Impala or Caprice with any size wheels, is the namesake of the show. The term's used in general to describe many cars with that look, including newer ones. But donks aren't the only things that show up: the SLABs, which stands for Slow, Low and Bangin', show up too. It's a time when music and cars come together and blend two segments of Southern car culture, the contest's employee said.

The Donk Contest celebrating those cars, which was long just a casual get-together everyone knew about each year, lost its location when the long-troubled Highland Mall closed in 2015. When mall closed, the show's website says it needed a more formal arrangement to keep the gathering alive.

(It's also worth noting that Austin has something of a checkered history with playing host to Texas Relays—also said to bring out a heavy police presence. Despite the city's unapologetically liberal, blue image in a red state, it's often accused of being hostile to the predominantly black Texas Relays crowd, with bars and restaurants on Sixth Street closing entirely rather than serve patrons.)

That's when, according to the Donk Contest's website, longtime Austin resident Deykon Harris took over as the show's organizer. Harris didn't want to lose the event, and had past experience with putting together big shows. (He couldn't be reached for comment for this story.)

He's been in charge ever since—or at least he was, until this apparent mis-investment in cryptocurrency threatened to derail the event entirely, according to Reddit and social media posts as well as interviews with people involved.

The Investments

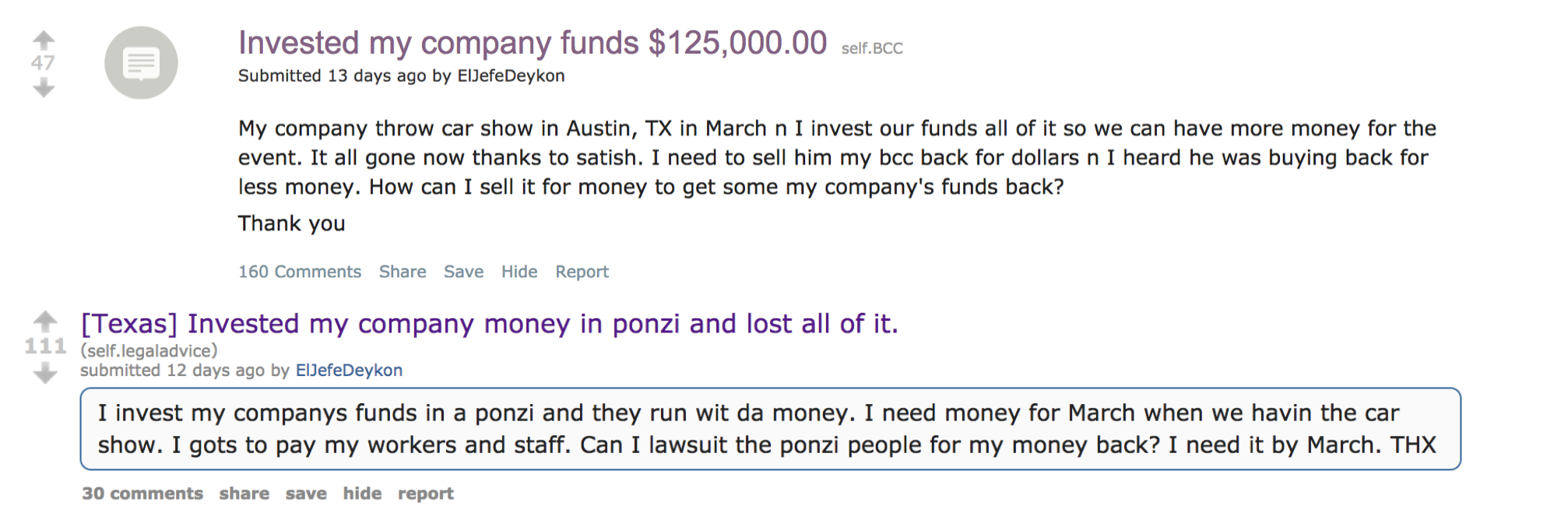

Issues around this year's show started when an account appearing to belong to Harris made some Reddit posts in January. The first was in a subreddit for users of Bitconnect, a cryptocurrency investment platform suspected by internet users of being a Ponzi scheme. The second post was in a subreddit for legal advice.

In Ponzi schemes, the people in charge often don't invest the money. Instead, they use the new investments to pay back earlier investors and usually keep some for themselves. The scheme falls apart when the flow of money from new investors slows down or when a lot of investors cash out. The SEC added an informational page about Ponzi schemes in digital currencies way back in 2013.

The allegations of Bitconnect being a Ponzi scheme are still just allegations, but it abruptly ceased operations earlier in January after Texas and North Carolina issued cease-and-desist orders.

The employee with the show told Jalopnik that the account that posted those threads does belong to Harris, and his posts seemed innocuous enough: Harris just wanted his money back.

(Aside from Harris' claims being backed up by the show's employee, Jalopnik could not visually confirm that these cryptocurrency transactions occurred.)

Across the two threads, Harris said he invested $125,000 of the show's funds into Bitconnect in December 2017 and "lost all of it." Harris said on Reddit he needed the money back by the time the show takes place in March to pay his workers, and asked if he could sue the people running the scheme in order to do so. He also added that the funds came from "wealthy investors" in California.

The timeline of Harris' investments lines up perfectly with the highly covered peak of Bitcoin, which, it should be noted, is a different type of cryptocurrency than the account said to belong to Harris' talked about investing in. Regardless, cryptocurrency was on the rise both in value and in the news cycle in the later months of 2017, and Bitcoin peaked around the time these investments were apparently made.

It took a hard dive soon after, right around the time the account appearing to belong to Harris began saying the investments weren't turning out as planned.

The contest's Twitter account and Facebook page posted statements soon after the Reddit threads to say multiple people came forward to offer financing and sponsorships to keep the show on for this year. Subsequent posts around Jan. 19 said new the financing came from a cryptocurrency lending project, Davorcoin, which the show tweeted was a free loan that would be paid back in two months.

Since then, the Texas State Securities Board announced an emergency cease-and-desist order against Davorcoin. The Feb. 3 announcement said Davorcoin was an "unregistered firm ... selling unregistered securities," and the state's Securities Commissioner, Travis J. Iles, warned investors not to buy into the cryptocurrency hype before understanding what they're investing in.

On Feb. 7, the Donk Contest's Twitter page posted this:

It's not immediately clear what the organizers meant here; we reached out for clarification.

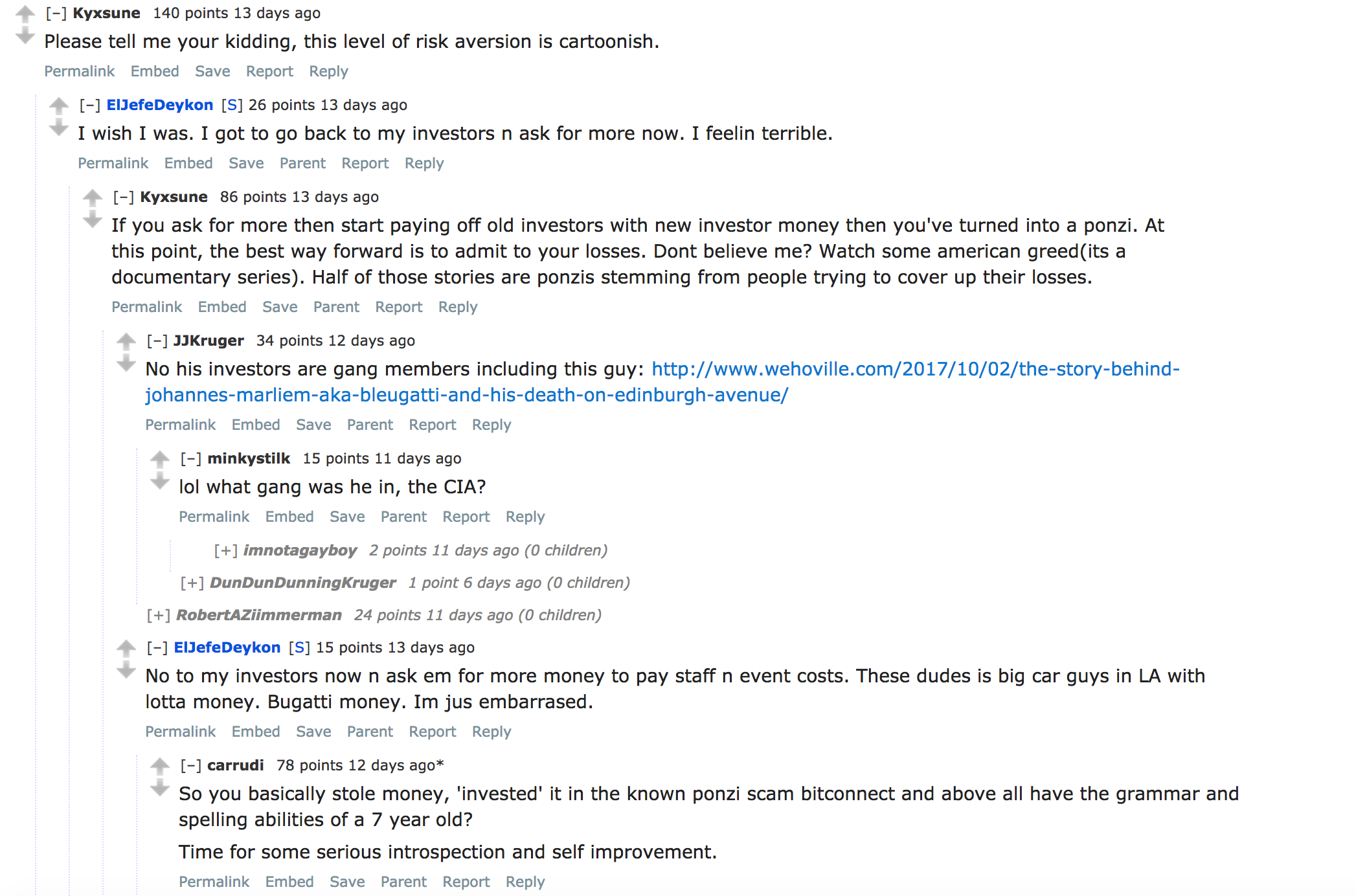

Before the apparent issues with Davorcoin even went public, Reddit users—a group seldom known for their overwhelming compassion—called Harris' "level of risk aversion ... cartoonish," calling his investors gang members and Harris an "authentic [slur for intellectually disabled people]" with the "grammar and spelling abilities of a 7-year-old," and accusing him of stealing the original investors' money and reinvesting it.

Those same types of comments began showing up on the Donk Contest's social-media pages and posts online. The show's Twitter page defended Harris, saying he "is not a [the same slur as before] and it was a mistake" and defending the contest as a whole against people making fun of it. YouTube comments rolled in on the contest's documentary, asking if Bitconnect was "treating [the contest] well," making fun of the contest itself and talking about the investments.

Despite the internet's judgement, the employee with the contest told Jalopnik that Harris, "as nice of a person as he is," was too easily trusting with the investments.

All the while, Reddit posts from what's believed to be Harris' account showed he was taking internet users' words to heart: He told people he'd been crying, felt terrible, that he was embarrassed, that the investment was honest, and the he has feelings, too.

Then, Harris appeared to simply disappear. On Jan. 20, the show's social-media pages asked anyone who knew Harris' whereabouts to have him contact the people involved with the contest, because they were "very worried about him."

The Donk Contest had lost a lot of event staff and was down to three contractors by Jan. 26, the employee who preferred not to be named told Jalopnik. Ten days after the original message about Harris, the employee said no one left at the show had heard from him yet.

They're not taking it too seriously, though, as they think he's laying low after the issue got so big on the internet.

"I believe it's more of a situation where he felt embarrassed and is working to resolve the payroll issues before coming back," the employee said, adding that the internet chatter makes the situation sound crazier than it is. As far as those with the contest know, no investors are mad—only disappointed in Harris.

The employee with the show said it should go on as planned, with 40 cars already registered, expectations of up to 500 people, and several big Houston rappers committed to attend. The show hasn't announced a location yet, the employee said, but plans to do so in March.

At the time of writing, records show that neither Harris nor anyone involved with the Donk Contest has filed a lawsuit against Bitconnect in U.S. courts.

Officials with the Austin Police Department told Jalopnik at the end of January that neither a missing-persons report nor reports of financial crime by or against Harris have been filed there.

The Donk Show's website listed Davorcoin and a shop called T.J. Jewelry & Co. as its official sponsors at the time of the investments, but T.J. Jewelry's owner, who goes by simply T.J., told Jalopnik his store isn't an official sponsor. He said he got calls about this around the same time last year from a shopping center called the Domain, where the Donk Contest was slated to happen.

The employee also said they "just learned" at the end of January Harris had paid "random people for sponsorship and promotion deals who had no connection to the companies," which Jalopnik couldn't confirm as Harris hasn't been available to contact. The contest only had T.J. Jewelry, which denied being a sponsor, and Davorcoin as its official sponsorships on the website as of the end of January.

By Feb. 2, the T.J. Jewelry logo had been removed from the show's website. As of Feb. 8, the Davorcoin logo remains there.

Harris' Reddit account shared a Jan. 31 post from the Donk Contest Twitter page which seemed to relate to that subject, which said the following: "Another blow as we just found out payments were made to people pretending to represent certain companies who had no affiliation with said companies. We live in a sad world but it will not stop us from accomplishing our goals."

The Problem With Cryptocurrency Scams

The Donk Show and Bitconnect, according to the posts, became intertwined in the midst of a wave of positive news about Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Crypto seemed like it was only on the up, but few noted how ripe the poorly regulated system was for scams, and many were caught up.

A bitcoin currency unit climbed from $1,000 to almost $20,000 in value in December. People started making high-profile car purchases in cryptocurrency. Those who didn't cash in notoriously sunk into regret over missed opportunities for instant wealth.

That was the good period, and it didn't last long. Bitcoin dropped below half of its peak value in January. Email vulnerability on Reddit led to stolen Bitcoin cash. Money went missing from cryptocurrency exchanges.

Then there were the investment platforms eventually accused of being scams like Bitconnect, which unfortunately might have roped Harris in.

TechCrunch reports that Bitconnect, which shut down after the cease-and-desist orders, was an anonymously run platform—with anonymity being a common approach in alleged cryptocurrency scams. Users would buy in by loaning their cryptocurrency to Bitconnect, which promised high returns that differed based on how long the loan was for. It also had a big emphasis on its referral feature, which led people to believe it funded the big returns with new investors' money.

The token Bitconnect used, called BCC, plummeted by 80 percent before the site shut down. According to TechCrunch, many Bitconnect users were "suffering severe financial losses in terms of USD or Bitcoin" after investing.

There are currently four court cases against Bitconnect on record in U.S. district courts, with one, Paige v. Bitconnect, accusing the platform of "scamming thousands of Kentuckians and hundreds of thousands of Americans out of millions and millions of dollars."

The lawsuit accuses Bitconnect of being "both a pyramid scheme and a Ponzi scheme" that relied on money from new investors. When Bitconnect shut down, the lawsuit alleges, it left this particular investor "with BCC, which is either entirely worthless or has significantly less value than Bitconnect promised."

On whether it would be possible for Harris and the show to recover the funds said to be invested in the alleged Ponzi scheme, David Barrett at Boies, Schiller & Flexner LLP, who has represented some of the plaintiffs seeking recourse in the famous Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme, said it all depends.

There are a lot of loose ends on either side of an investment scandal like a Ponzi scheme, and once lawsuits begin, it's all about tracking down the excess money from the scheme and suing people involved along the way. The amount of funds that can be recovered determines how much investors who lost money can get back, which is sometimes a lot and sometimes none.

"There are a number of avenues to possible recovery for a fraud, a Ponzi scheme or a pyramid scheme," Barrett said. "The problem is that there can be many legal and practical obstacles to actually recovering any dollars and it can take a long time. By that, I mean several years."

"It's very hard to predict whether the investors who were defrauded will ever wind up recovering any money. I can tell you that in general in securities fraud litigation, if there's a recovery at all, it averages probably 5 percent or less of the amount that was actually lost by the investors. There are some cases where it can be a lot higher, but there are other cases where it's lower or zero."

Barrett said for an investment as small as $125,000, it wouldn't make sense for Harris to fund litigation on his own. But he and other investors can benefit from class-action suits brought on by plaintiffs who file "individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated," of which there are two in the U.S. court system.

If the lawsuits are successful, Barrett said, investors will be notified as best as possible to bring forward proof of their investments and losses. If there is no definite paper trail documenting all investors, courts will go to extreme lengths to try to get investors' attention, including with ads in newspapers and the like.

As for the Donk Contest, its organizers are taking this hurdle as they do any other. The show, the culture and tradition has to stay alive. "We live in a sad world," the show's Twitter account said at the start of the month, "but it will not stop us from accomplishing our goals."

Hat tip to Tirey!