How America Built A 'Factory In The Sky' To Defeat The Nazis On D-Day

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

When WWII started aviation experts were convinced no one could mass-produce the big, destructive B-24 Liberator bomber. A month before D-Day, a Ford factory was on the verge of producing one an hour. In this chapter from his new book, A.J. Baime explains why it was pivotal to defeating the Axis powers on this day 70 years ago. – Ed.

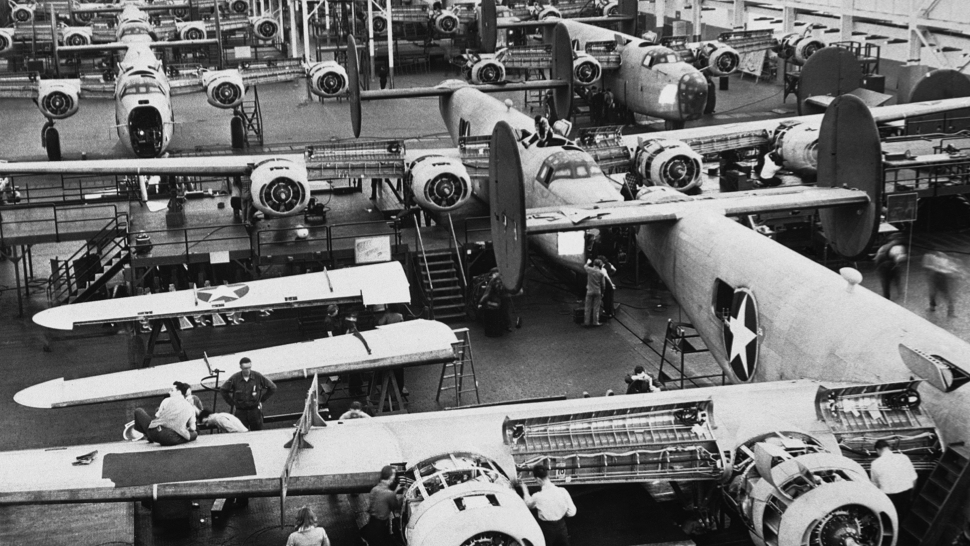

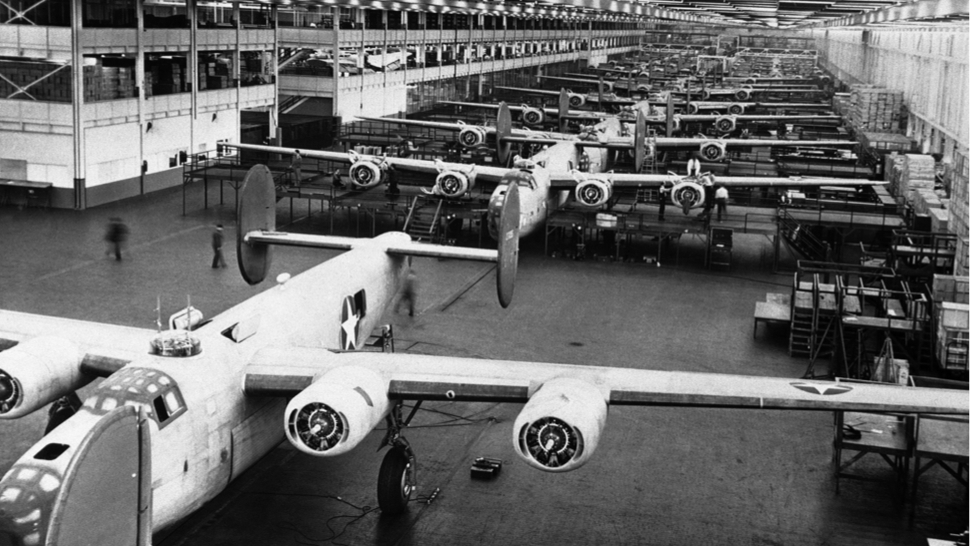

On May 4th, 1944, a month before the D-Day invasion, the machines at Ford Motor Company's Willow Run bomber plant in Ypsilanti, Michigan, shut down momentarily so that workers could gather outside the east end of the assembly building at 2:15 pm.

It was a beautiful spring day in southern Michigan, thousands of miles from the combat in Europe and the Far East. On a stage, the American Legion Edsel B. Ford Post Band played, the tubas honking out "America the Beautiful." Harry Wismer—one of the first big sportscasters and part owner of the New York Titans of the American Football League—grabbed a microphone, as master of ceremonies. The crowd had gathered for the presentation of the Army-Navy "E" Excellence award for the Willow Run bomber plant.

Willow Run had continued to accelerate all spring long, speeding toward its goal of a bomber an hour, 400 a month. For so long, the aviation experts insisted that the B-24—which was the biggest, fastest, most destructive bomber in the American arsenal at the beginning of the war—was too large to be mass produced. And now? In March 1944, Ford built 324 Liberators. April: 325. May: 350. Soon it would hit its mark of a bomber-an-hour; there was no doubt. The presentation of the Army-Navy Excellence flag signified the approval of Washington—that the experiment at Willow Run had fulfilled its promise, that Edsel Ford (recently deceased from what most believed was stomach cancer) and "Cast Iron" Charlie Sorensen had proven all the naysayers wrong.

On stage, Henry Ford II accepted the "E" flag from the Navy's Captain Robert Velz, lifting it triumphantly so it rippled in a light breeze as the crowds whistled and applauded. The band played the Star Spangled Banner while Navy men raised the E flag and the American flag on either side of the stage. Then Henry II took his place in front of the microphone and prepared to give his first speech as a representative of the Ford family. It was fitting that his first major official duty was to honor Willow Run. Henry II was standing in for his father, in Edsel Ford's most triumphant moment.

Henry II appeared different from a year earlier. His eyes were harder, less forgiving. His face had hardened too. In the months since he had left the Navy, under the careful tutelage of Charlie Sorensen, Henry II had grown into himself, confidant in the idea that he would not end up a footnote in the history of the Motor City. He'd begun to exhibit the fearlessness that would define him in later years, when he would become one of the most powerful businessmen in the world. The 26-year old Ford scion sipped in a breath and began.

"It is certainly with mixed emotions that we meet here today," he said. "Four years ago this spring there was no Willow Run. This land—1800 acres of it, covered today by a gigantic monument to industrial might—was producing agricultural products. But war was upon the world and our country's participation was nearing. Mass production of the B-24 Liberator bomber, the largest, fastest and hardest-hitting of them all, was handed to us as our job."

Henry II spoke of the engineering miracle, of the Truman investigation, of the overwhelming social problems that accompanied this industrial adventure. How everything had gone so wrong, and how, through sheer determination and patriotism, the men and women who ran this factory and worked inside it had turned it around. Now everything was going right.

"It is just another proof that in America we can do the impossible," he said. "And that the impossible always proves the nemesis of those enemies of peace and progress who attempt every so often to upset our relentless struggle upward toward a better world for all men everywhere."

In the White House, the President was studying Top Secret documents in preparation for D-Day. A military force staggering in size and complexity had already begun to amass in Britain, a force that would swell until it reached 175,000 men, 50,000 vehicles of all types, well over 5,000 ships, nearly 11,000 airplanes, plus guns, bullets, medicine, food, and cartons upon cartons of cigarettes from the tobacco fields in the American south. This was the Arsenal of Democracy at its height, built not just by the U.S., but with fantastic contributions from Britain and Canada.

In the Battle of Production, the Nazis were proving an extraordinary foe. Suffering the brutal ravage of the Allied bombers, their production of war munitions continued, the factories filled with slave labor. So ingenious were Hitler's engineers, so nimble and intelligent was his top production man Albert Speer, Germany had managed to move machine tools out of bombed out factories and into underground caves. Airplane engines were being constructed inside mountains. Church bells were melted so that the metal could be used for munitions. One company alone, Krupp, was producing U-Boats, 88 anti-aircraft canons, guns, tanks, and amour of all kinds.

Still, the confidential reports regarding production in America that crossed Roosevelt's desk in the spring of 1944 were nothing short of miraculous—specifically when it came to four-engine bombers. According to a March 1944 top secret report to the President: "Heavy bomber production was again outstanding with 1,508 acceptances of B-17s and B-24s." The month before the D-Day invasion, a confidential War Progress Report stated: "May was a great month for planes...with heavy bombers making a brilliant showing." Simultaneously, the President received secret wires to his map room telling of the Allies' mastery of the skies in Europe. On May 8, 1944: "Operations of our Air Forces during the past four months have definitely resulted in marked depletion of German Air Power."

In the final hours before D-Day, Roosevelt received another confidential production report. A chart showed "The 'Big Ten' of the Invasion," listing the number of aircraft mass produced between 1940-1944. Number one on the list: the B-24 Liberator. Over 10,000 of them had taken flight. Nearly half of those built so far rolled out of Willow Run, and in the coming months, Ford's production would increase until it was making 70% of the nation's Liberators. At the time of the invasion, The Liberator had already become America's most mass-produced airplane of any kind, ever.

By June 5, 24 hours before D-Day, the tension in the White House had grown unbearable. Looking at the President, Eleanor Roosevelt saw that her husband had become elderly. He had given all he had to his country—now in his fourth term in the White House and his third year of the war. According to one Presidential secretary, "every movement of his face and hands reflected the tightly contained state of his nerves." On that very day, Rome fell to the Allies. Roosevelt wrote to Churchill: "We have just heard of the fall of Rome and I am about to drink a mint julep to your very good health." But no one could celebrate in the White House.

Operation Overlord—D-Day—was the largest, most hazardous military enterprise ever to be undertaken. The President had called on his nation to build the Arsenal of Democracy, and his nation had come through for him. All he could do now was sit and wait for news from Europe.

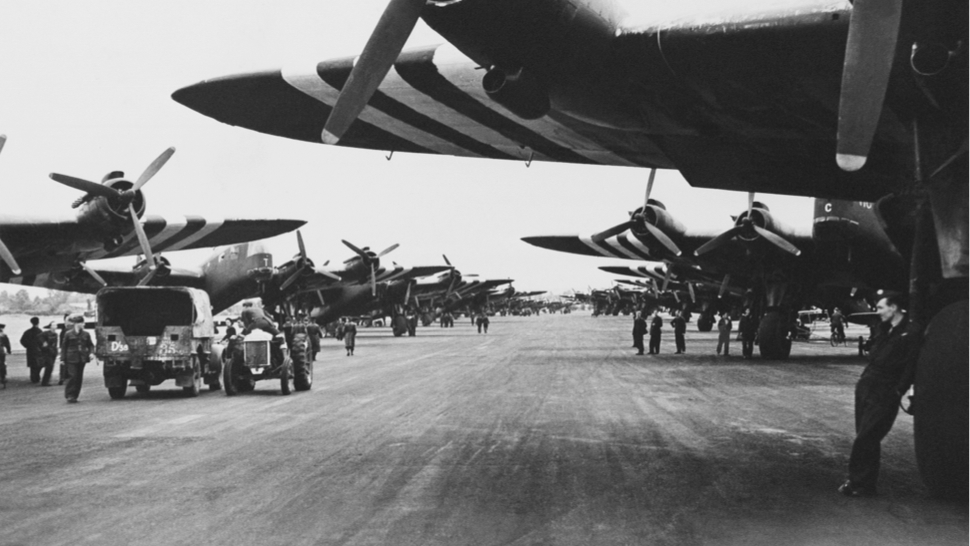

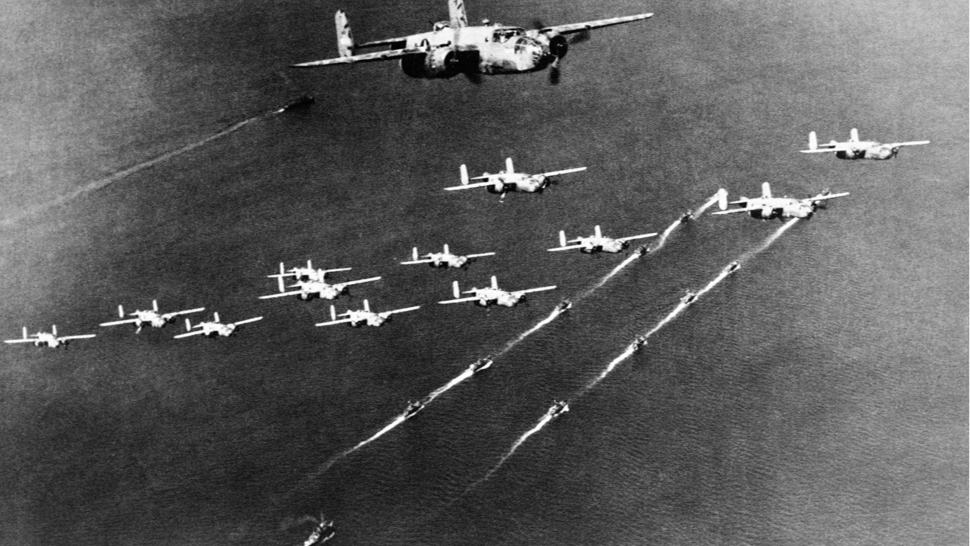

Under the cover of night in the early hours of June 6, 1944, the largest air armada in history banked downward over the beaches of Normandy, flying just 500 feet over the breaking waves. The decibels were immeasurable. "As dawn broke," recalled one Captain standing on the beach, "we could observe one of the most impressive sights of any wartime action. Wave after wave of medium and light bombers could be seen sweeping down the invasion beaches to drop their bombs."

"Rosie the Riveter back home had been very busy," said another American who witnessed this scene.

For CBS radio, Murrow was reporting from London, watching the bombers take off on their D-Day missions. "Early this morning we heard the bombers going out," he announced. "It was the sound of a giant factory in the sky."

The first planes to bomb the beaches were B-26 Marauders, built by the Glenn L Martin company outside Baltimore. They were powered by Pratt & Whitney double wasp engines, a huge number of them built at the Rouge factory in Dearborn, Michigan, under the supervision of Charlie Sorensen and Edsel Ford.

At the same time, 1,200 American heavy bombers swung low over the beaches and over the oil refineries of Ploesti, Romania. Over those oil refineries, 407 B-24s made their attack runs on D-Day, delivering knockout blows.

Flocks of Waco wooden invasion gliders carrying equipment and airborne troops whistled engineless over the Normandy beaches, nearly 1500 aircraft strong. The Wacos had been built by many companies, such as Michigan's Gibson Refrigerator and Arkansas's Ward Furniture Company. But no outfit had built more of those gliders than Ford Motor Company. The pre-dawn landings came in two waves: one named Chicago, the other Detroit.

The Allied forces rolled out their tanks and equipment and guns. Over 1,000 landing craft unloaded men, tanks, jeeps, and trucks. In the first 15 hours, American forces pushed 1,700 vehicles onto Utah Beach alone (there were five landing beaches in all).

By the time Overlord's Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower, set foot on the sand, it was littered with broken vehicles, torn apart by enemy gun and canon fire. "There was no sight in the war that so impressed me with the industrial might of America as the wreckage on the landing beaches," he recalled. "To any other nation the disaster would have been almost decisive. But so great was America's productive capacity that the great storm occasioned little more than a ripple in the development of our build-up."

From day one of World War II, the airplane had revolutionized combat. In the war's climactic battle, it remained a key weapon. On the D-Day beaches, Eisenhower was joined by his son John, who had just graduated from West Point. Above them, Allied planes of all kinds flew over at low altitude, the furious exhaust notes of the engines driving through the percussion of gunfire.

"You'd never get away with this if you didn't have air supremacy," John said to his father.

"If I didn't have air supremacy," General Eisenhower answered, "I wouldn't be here."

—

This story originally appeared in The Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War. Copyright © 2014 by Albert Baime. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Photo Credits: Getty Images, AP Images, Tom Image By Jim Cooke