High-Tech Ferries Tarnished The Legacy Of Transatlantic Ocean Liners In The 1990s

A record contested by ocean liners was last broken the same year AOL bought Netscape

The record for the fastest transatlantic crossing typically conjures images of bygone ocean liners with opulent amenities and decadent meals featuring roast squab and foie gras. Not stuffed crust pies from Pizza Hut. During the 1990s, high-speed catamaran ferries upended the idea of what ships could be the pinnacle of maritime travel. However, historians and enthusiasts fought tooth and nail to protect the ocean liner's legacy.

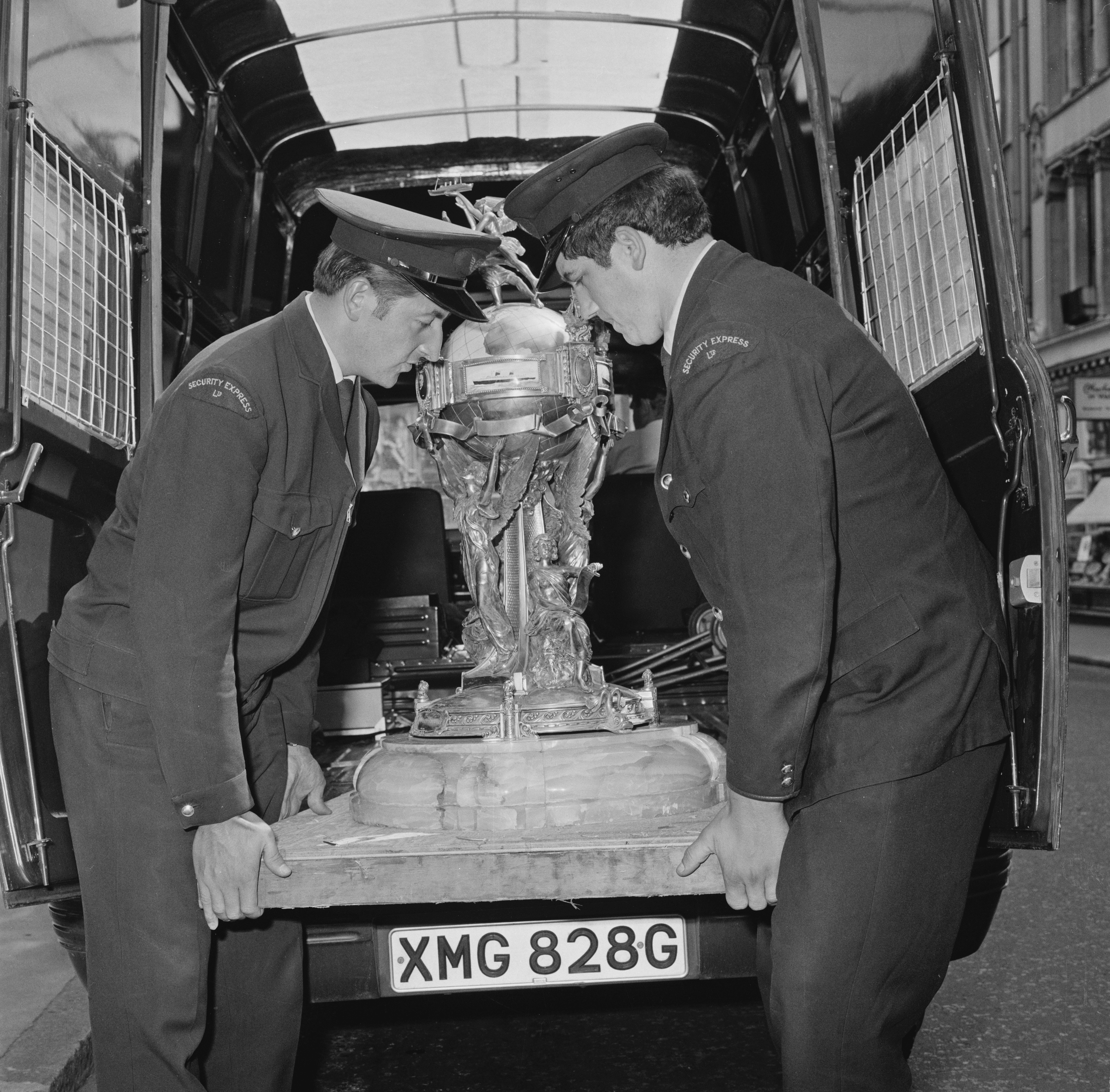

At the center of this dispute was the Hales Trophy. Shipping companies, like Titanic's operator White Star Lines, fought each other to complete the fastest transatlantic crossing with a passenger liner and earn the unofficial Blue Riband as a mark of prestige. The Hales Trophy was created in 1935, but only three ships ever won the award due to World War II and the rise of passenger air travel.

The SS United States won the Hales Trophy in 1952 after a three-day, 12-hour voyage from England to New York. The de Havilland Comet, the first jet airliner, entered commercial service that same year. No other ship challenged the record and previous record-holding ocean liners were retired during the 1960s. United States Lines took its record liner out of service in 1969.

USL loaned the Hales Trophy to the U.S. Maritime Marine Academy Museum on Long Island to be displayed as a relic of the bygone age. However, if there's a trophy to be won, someone going to try and take it. British music and retail magnate Richard Branson broke the record in 1986 with a 72-foot powerboat. USL and the museum refused to hand the Hales Trophy over on the basis that the award's deed stipulated that it was for passenger liners. It also allowed officials to stick up their noses and derided Branson's challenger as "a little toy boat."

A new breed of ship arrived on the scene in 1990, high-speed catamarans. Australian manufacturer Incat brought fast catamaran ferries to market that year. Multi-hulled cats have two distinct advantages compared to traditional monohulled ships. First, they are far more stable. Second, they face far less water resistance while moving forward.

Incat built a 241-foot-long catamaran ferry for Hoverspeed, an English Channel ferry company. The ferry named Hoverspeed Great Britain was fitted with four massive 4,825-horsepower V-16 marine diesel engines that powered four water jets. A total power output of 19,300 hp might sound impressive, but the SS United States was rated at 240,000 hp.

Hoverspeed Great Britain crossed the Atlantic two hours faster than the SS United States in June 1990 and the controversy began. USL and the museum again refused to hand over the trophy, but the ferry was undisputably a passenger vessel. They considered fighting legal action with their lawyer telling the New York Times:

"Certainly, the museum does not own the trophy. If the Queen Elizabeth 2 challenged for the trophy, there would be no problem in turning it over to a qualified passenger liner."

The lawsuit was called off once it was realized how expensive the legal fees could be. However, this wasn't the end of the story.

Off the popularity of James Cameron's "Titanic," Carnival Cruise Lines thought it could capitalize on the fervor for the golden age of ocean liners. Carnival went all in, buying the Cunard Line and announcing plans for Queen Mary 2 in 1998. The cruise line also commissioned two replicas of the Hales Trophy, one to display on a ship and one to loan to the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy Museum permanently.

Even will a new replica filled the empty plinth, museum curator Frank Braynard was still bitter about the saga. He told the New York Daily News in 1998:

"We were very proud of it, and along came this damn little ferry boat and they claimed it," said Braynard. Sherwood sued for the trophy in an English court. "We fought like hell to keep it," said Braynard. But eventually, they surrendered when counsel advised that they were fighting a losing battle.

Also in 1998, two different Incat-built catamaran ferries shattered the mark set by Hoverspeed Great Britain over the span of two months. The second run in July 1998 still stands as the record today. Cat-Link V, operated by Danish ferry company Scandlines, crossed the Atlantic from New York to England in just 2 days, 20 hours and 9 minutes.