Here's What Happened When I Put A $120 Craigslist Engine Into My Jeep

I bought a motor that had been sitting in a field for $120. Well, I just plopped that literal lawn ornament into my Jeep XJ.

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

About a year ago, I blew up my Jeep's engine trying to drive through a deep mud pit. The next day, I bought a motor that had been sitting in a field for $120. Well, I just plopped that literal lawn ornament into my Jeep XJ. Here's how that went.

You see, $120 for an engine is unbelievably cheap. Unheard-of, cheap. Running 4.0-liter sixes on Craigslist often run around $350, or more. This was either a deal or an expensive paperweight.

On one hand, it had been sitting in the grass field next to a guy's barn for who knows how long with nothing but a little cup over the throttle body. On the other hand, I had checked the oil level, and it was on point. Plus, I had turned the engine over by hand, and it spun freely with little effort. So, "screw it," I thought, "what could possibly go wrong?"

After stringing the motor up with chains and dragging it to the base of my $600 XJ's rear bumper with a Farmall tractor, four of us burly men (okay, it was three burly men and me) lifted the legendary engine into the back of my XJ, bottoming out the suspension and sending my XJ's nose sky-high for my ride home with my loot.

The engine, once removed from my Jeep's trunk and bolted to an engine stand, remained in my garage for nearly a year. Until just a few weeks ago.

Wrenching On The $120 Engine

After all the dust settled from my Moab Jeep XJ project, I could finally work on getting my red XJ back on the road. But I wasn't just going to toss in the cheap Craigslist motor all willy-nilly-like, you see. I'm not that nuts.

As I didn't like the prospect of having to pull the engine for the third time in a year, I decided to tear the cheap Craigslist motor apart to see how it looked inside. No point in installing an engine if it's completely toast, right?

While I was in there, I decided to replace all the parts that tend to go bad on these venerable Jeep engines: the lifters, head gasket, valve cover gasket, oil pan gasket, oil pump, freeze plugs, water pump, timing chain, rear main seal and thermostat.

I pulled most of those parts from my old engine, as just before the "incident," I had actually refreshed the XJ's 250,000 mile motor. That refresh didn't last long.

Inspection

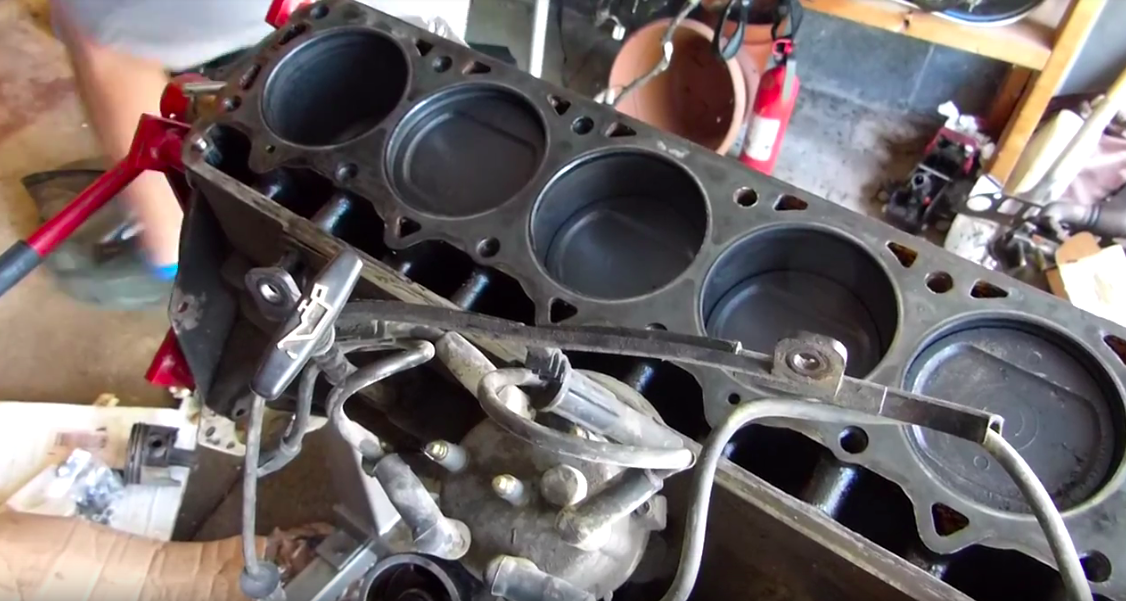

The first thing I did was yank the head and oil pan to see if there was any abnormal wear in the cylinder walls, or if there were any chunks of metal in the pan. I also took a glance at the camshaft, and just poked around to see if there was any sort of crusty gunk inside.

Everything looked good. The cylinders were clean and the "lip" between where the piston rings ride and the untouched cylinder wall was reasonable, meaning there wasn't a lot of wear.

The camshaft also looked good, with normal discoloration, but no noticeable wear. Rocker arms, lifters, and all oil passages were nice and clean. The same can not be said about the coolant passages, however.

Freeze Plugs

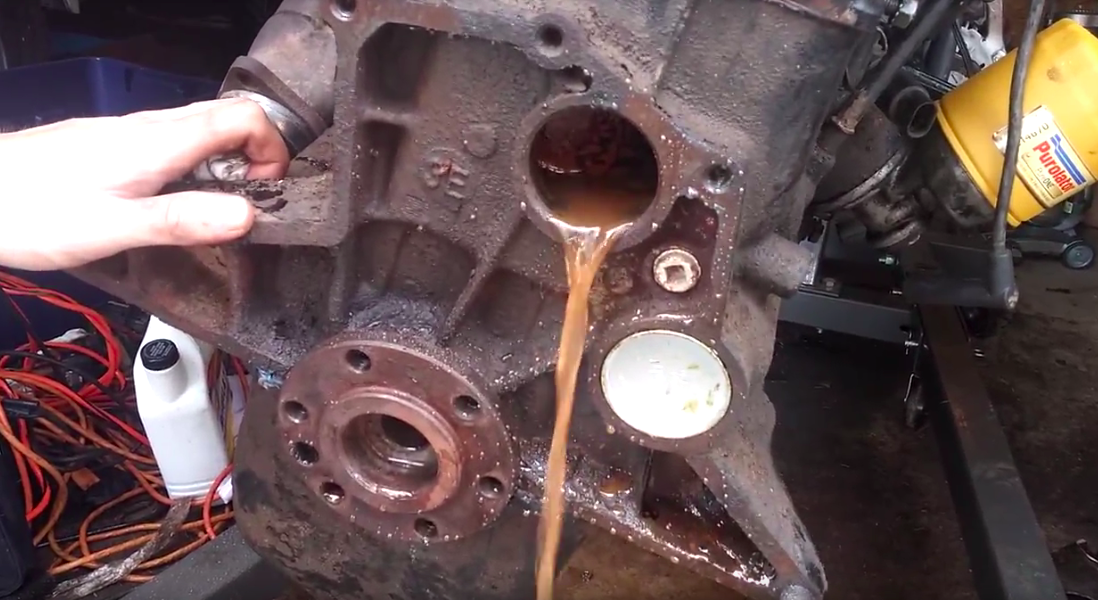

The Rust Gods had unleashed a storm on the coolant passages of this poor engine. No surprise, though, as this thing was sitting in a field with the thermostat housing port wide open and pointing straight up, completely exposed to the elements.

One look at the coolant passages and I knew I had to replace all my freeze plugs for fear that they might be rusted through. And unfortunately, some freeze plugs are wedged between the engine and transmission, meaning getting to them later would be a gigantic pain in the butt. Better I get them knocked out now.

And I mean literally "knocked out." I lined up a punch with the bottom of the old freeze plugs and hammered it with a sledge, causing the plugs to rotate. Then I just grabbed the little metal discs with vice grips and yanked them out. Simple as that.

Once I had the plugs out, I took a garden hose to my thermostat housing, and shot loads of water through the system, yielding all this rusty gunk:

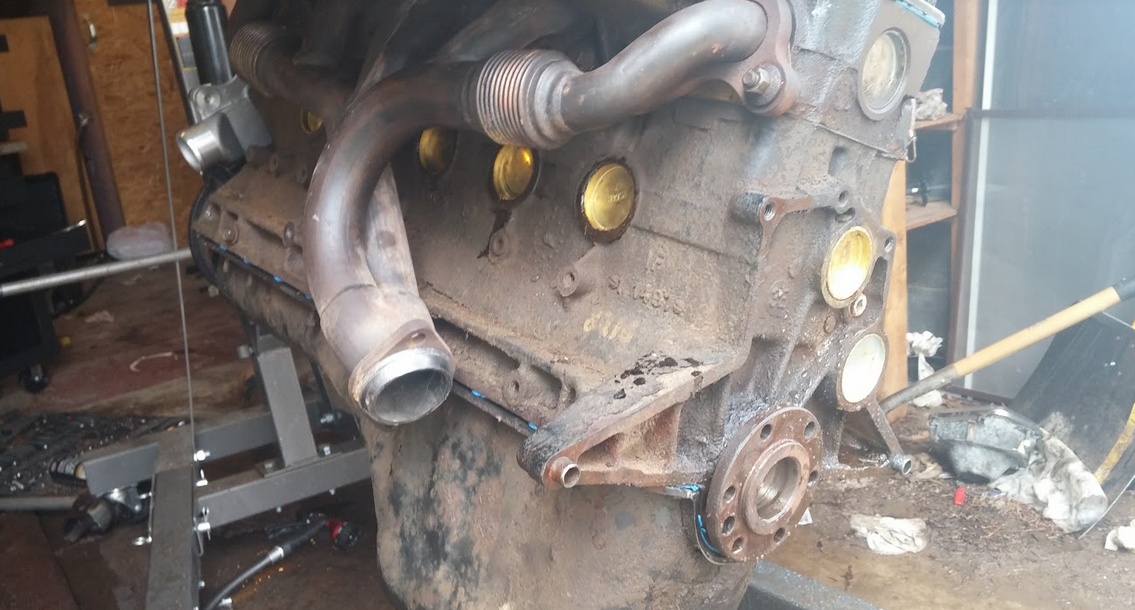

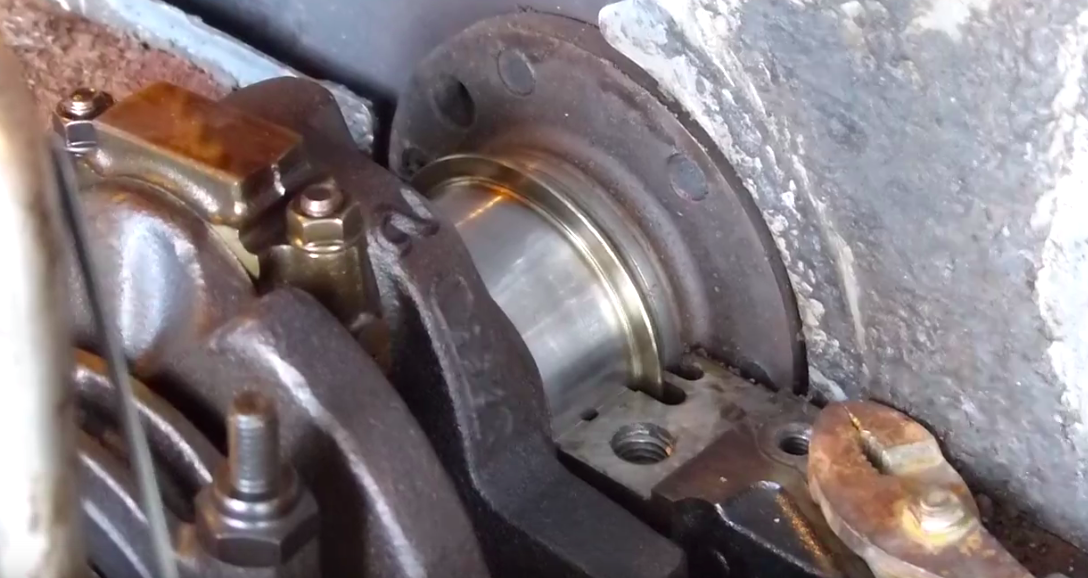

Then I replaced the plugs with brass ones (more resistant to corrosion), which I froze so they'd contract, lathered with Shellac Indian Head gasket, and pressed into the block with a sledgehammer and giant socket I had rented from O'Reilly Auto Parts.

Just look at those freeze plugs. Man they look good:

Lifters

The next step was to replace the lifters. On Jeep 4.0-liters, lifters don't go bad that often—usually only on high-mileage cars or ones that have been improperly maintained.

But, in my wisdom, I flipped the engine upside down with the cylinder head off, and all the lifters spewed out onto the floor. The lifters themselves were fine (they're really hard metal), but they were mixed up— I no longer knew which lifter went in which hole.

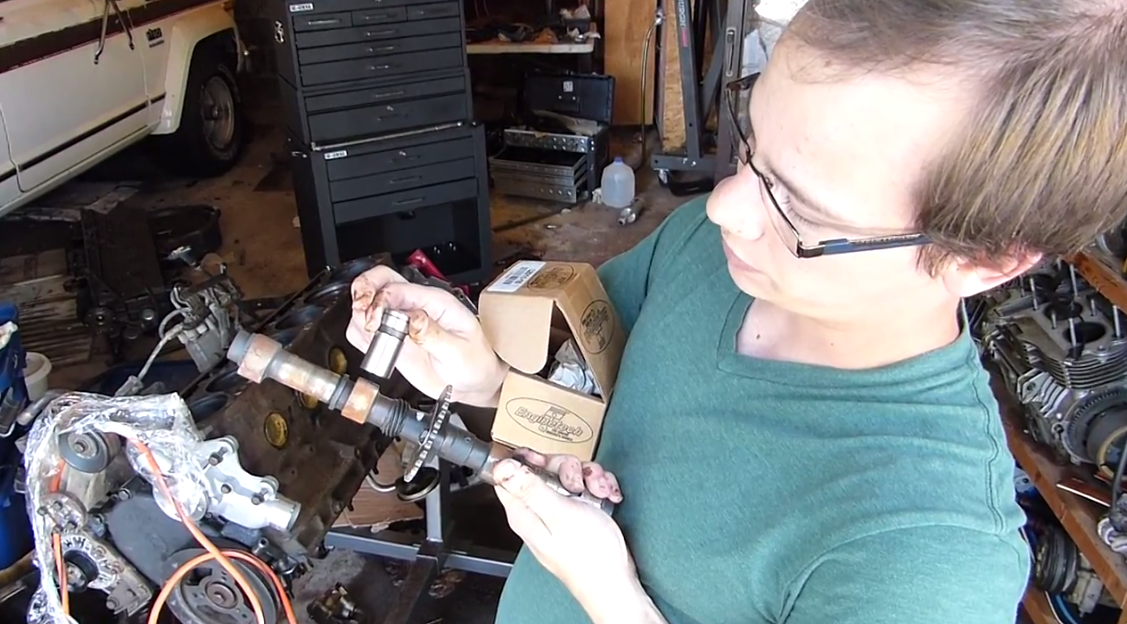

And since the lifter rides along a lobe on a camshaft (like the one in my left hand in the picture above), the lifter wears in a unique way to match that particular lobe. So putting a lifter, which has worn to match one cam lobe, onto another cam lobe is a recipe for disaster (i.e. that cam lobe is going to be wiped flat before you know it).

So I bought 12 new lifters for about $45 (ouch), coated them in assembly lube, and fished them into their holes with a magnet. Here's a closer look:

Rear Main Seal

The rear main seals on these Jeeps are notorious for leaking all over the place, so I wasn't about to just chuck the motor in without swapping mine out. After dropping a ridiculous $18 at the parts store for this little two-piece seal, I began extracting the old one.

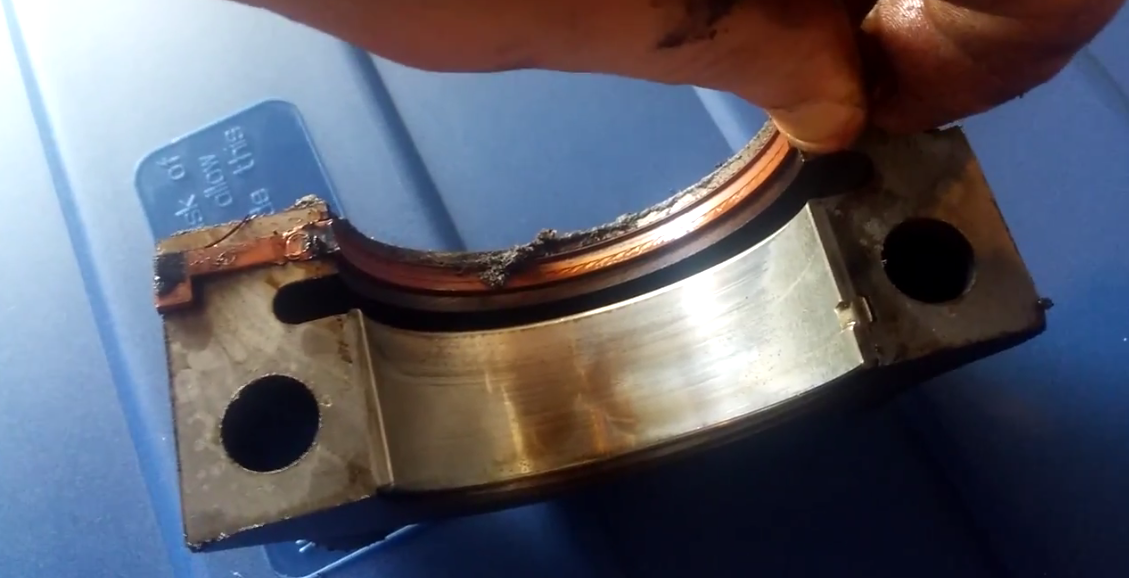

To do that, I had to remove two bolts holding the main bearing cap to the engine block. That bearing cap has a journal bearing attached, as well as half of the rubber rear main seal.

The other half is between the block and the crankshaft, and removing it is a gigantic pain, as there are only two tiny bits of it actually showing (each end of the C-shaped seal). I had to use a small punch to tap the seal so it would rotate around the crankshaft (without accidentally nicking the crank's bearing surface) and I could grab it with my hand:

Eventually, I had my rear main seal free:

Installation should have been the reverse of removal, but trying to shove a C-shaped seal into that channel between the crankshaft and the block required the use of a specially shaped wedge (I used a McDonald's straw) and some dish soap.

Surprisingly, that wasn't as hard as installing the other half of the seal onto the bearing cap, because the cap was covered in hardened, dry RTV sealant. I had a lot of trouble removing that sealant, so I just grabbed the clean bearing cap from my hydrolocked engine, shoved the rear main seal on it, and popped it on this engine—a very bad decision that ended up locking the engine up.

Eventually, I unbolted that bearing cap, cleaned the one original from this engine, and bolted it up it, allowing the engine to once again spin freely.

From there, I replaced the timing chain, water pump, oil pump, and a whole bunch of other gaskets, all of which I've already shown how to replace in my refresh post of my now-hydrolocked engine. With everything buttoned up, it was time to plop this engine into the Jeep and pray.

Installing The Engine Into The Jeep

The first step in installing the engine was shoving the torque converter onto the transmission input shaft. Luckily, I had read online that you need to push and spin the thing against the input shaft until it makes three distinct clicks. Otherwise, it's not be in all the way, and when you try bolting up the engine, things will get awkward.

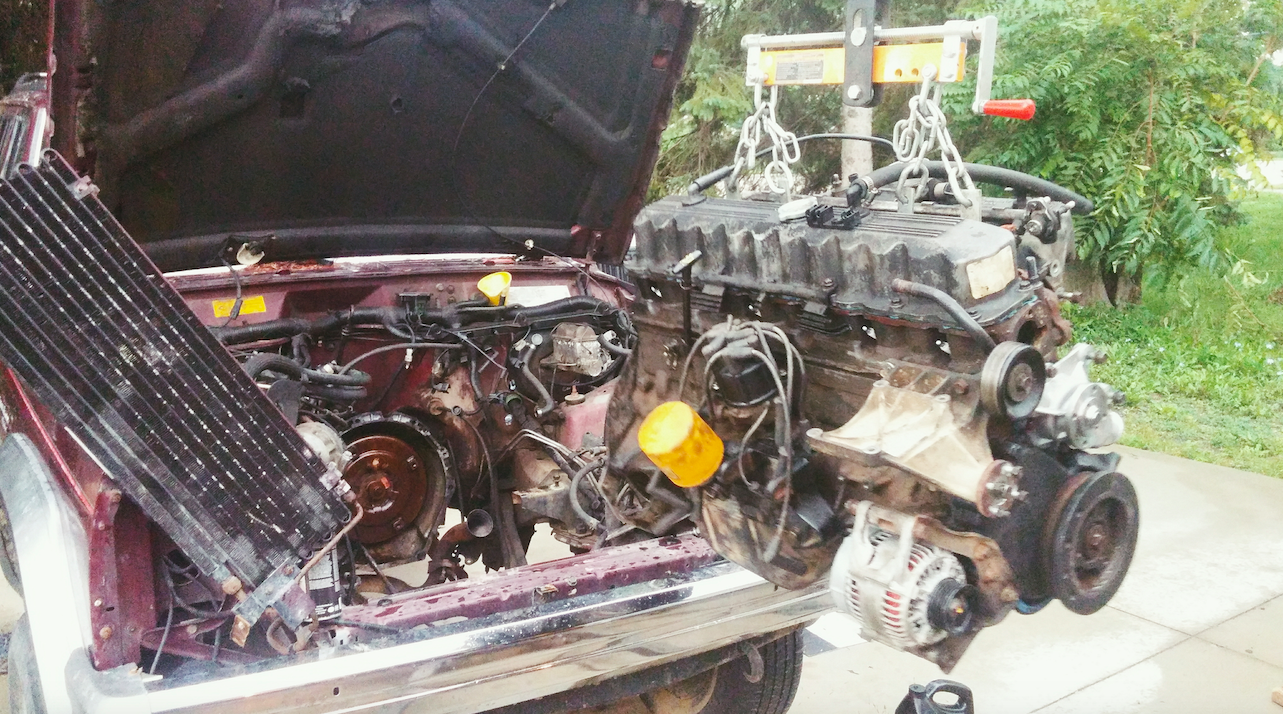

Once I was sure the torque converter was in, we hooked up some chains to the engine, unbolted it from the stand, and slowly rolled the engine hoist towards the front of the XJ.

Then we dropped the sucker in:

I slid underneath to wiggle the transmission so the engine would slide right into the bell housing.

After bolting the engine to the transmission, my friends and I hooked up the wiring and coolant hoses, and I slid underneath to tighten the four bolts holding the engine's flex-plate to the torque converter.

This required my friend to rotate the engine via the crankshaft damper pulley. The first time we tried doing this, we learned that putting the wrong rear main bearing cap on had seized my engine, and even hanging off the breaker bar wouldn't get it to rotate.

Eventually, I removed the oil pan and bolted up the right bearing cap. We then rotated the engine, and I slowly (and I mean slowly—1/12 turn at a time) began tightening those four bolts between the flex plate and the torque converter.

That took over an hour, but once it was done, the Jeep—for the first time in a year—had an engine in its bay:

Firing It Up

With her all bolted up, the next step was to crank the engine over a bit with the fuel pump and ignition coil unplugged to get all the fluids moving. So I hopped behind the wheel, and turned the key to the "on" position for the first time since that that sad day at the off-road park.

I turned the key, and "Click." All the lights shut off.

There was no power.

So I brought in my friend Steve, who can diagnose any electrical fault better than anyone I know. He wiggled the battery connection. The lights turned back on.

So I grabbed a ratchet, and tightened the connection.

We tried turning it over. Still nothing! The Jeep had lost all power until, once again, Steve wiggled the connection. After fiddling with this for hours into the evening, the team and I were pooped, so we called it. The gods had not intended for this Jeep to fire up that night.

The next morning, I was pumped. It was time to see if the heart transplant for my first Jeep—the one I learned to wrench on— had been a success or failure.

But, seeing as I suck with all things electrical, and Steve was nowhere to be found, I had to somehow find a mechanical solution to this electrical problem. So I did what any electrically-inept person would do: I broke out the sledgehammer.

I gave the starter a few hard wails, and prayed. This was all my brilliant mind could think of as a solution—my best foot had been put forward. And somehow, it worked.

The Jeep turned over right away. So then I installed the fuel pump relay and ignition coil so this thing could try its hand at internally combusting. And it did!

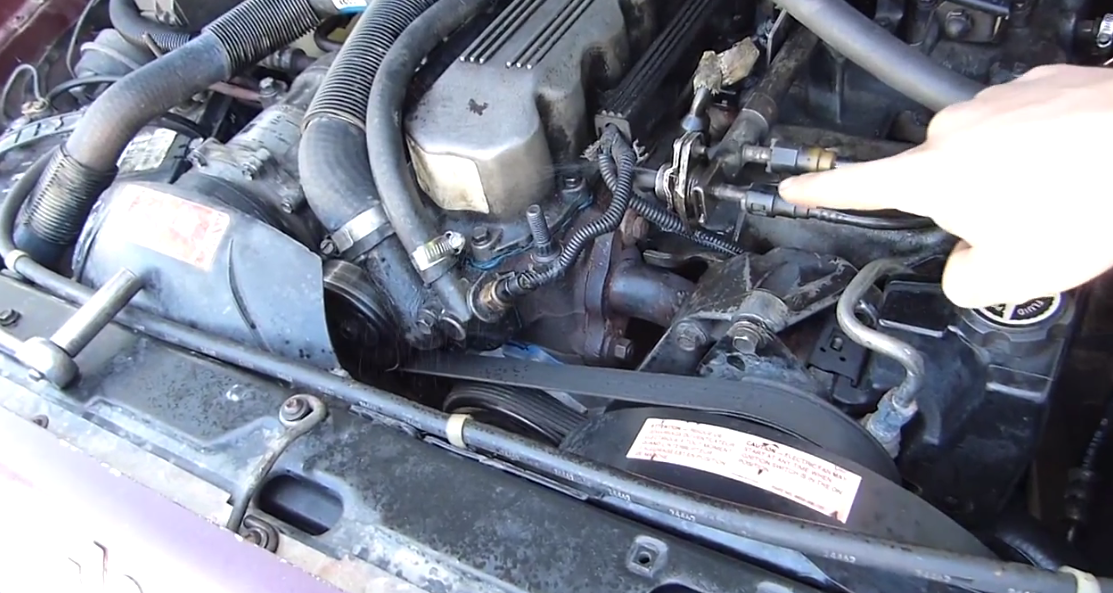

Unfortunately, it sounded like absolute shit. To find out what was going on, I walked towards the front, peaked into the engine bay, and was greeted with this:

A giant fuel leak from my fuel pressure regulator. There we go.

Not to worry, that thing has a couple of O-rings in it, and can be dismantled with a screwdriver in a matter of seconds. So I swapped out the O-rings, and fired her up again. The leak was gone, and it sounded better, but was idling at 3,000 rpm—screaming and waking up the neighbors.

Aware that idle issues with these Jeeps usually stems from a bad idle air control sensor (like the one shown above), I yanked mine out and cleaned it. The motor still didn't idle properly. Eventually I just replaced the thing with a spare I had from my other engine, and fired her up. And it sounded— well, let's let the smug look on my face describe how it sounded:

True perfection.

I've never heard a better sounding Jeep inline-six in my entire life, and I'm not just saying that because this thing only cost me $120 plus some lifters.

No, this thing sounds genuinely incredible. It idles perfectly smoothly, and—after taking it on a test drive—I'm convinced this thing makes as much power as any of these motors I've ever driven. And I've driven a lot of 4.0-Litre-powered Jeeps.

With the successful installation of this engine, I can now say I have in my lifetime experienced a true miracle. I bought an entire engine out of a field for $120, and the thing works flawlessly. What a beautiful world we live in.